Abstract

Sleep disturbance can contribute to negative health outcomes. However, sleep complaints have been under-recognized and undertreated in caregivers of ill family members. This systematic review describes the impact of family caregiving on sleep and summarizes factors associated with sleep disturbance in caregivers. A literature search using PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and CINAHL databases yielded 22 relevant research articles on family caregivers of ill adults. Analyses revealed that up to 76 % of caregivers reported poor sleep quality, and the proportion is considerably higher for female caregivers compared to male caregivers. Sleep measures indicated short sleep duration and frequent night awakenings. Characteristics of the care recipient, such as health status, and the caregiver’s own health status and symptoms, such as depression, fatigue, and anxiety, were associated with sleep disturbance in caregivers. These factors may help clinicians identify caregivers at highest risk for developing sleep disturbance and guide the family toward additional support.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Caregiving is an important public health concern in the USA, where it is estimated that approximately 66 million people serve as informal caregivers [1]. Informal care is defined as unpaid care provided to a relative or friend to help them take care of themselves or to a child with personal needs due to illness or disability [1]. Since approximately 66 % of informal caregivers are women [1], caregiving is a common issue that impacts women’s sleep.

Many caregivers report high levels of burden, stress, and depression [2, 3]. The long-term stress-related consequences of caregiving include increased risk for mortality [4] and morbidities such as coronary heart disease or stroke [5]. Caregivers also have a high prevalence of sleep disturbance. Prior reviews indicate that as many as 50–70 % of caregivers for a family member patient with dementia experience sleep disturbance [6••] and approximately 40 % of caregivers for a family member with cancer reported sleep problems [7••]. The most common types of sleep problems in caregivers of adults with cancer are short sleep duration and nocturnal awakenings, resulting in daytime dysfunction [7••]. Sleep disturbance contributes to adverse health outcomes and poor quality of life for caregivers [6••, 8]. However, sleep disturbance in this population is under-addressed and undertreated [6••].

If clinicians are to prevent or ameliorate sleep disturbance and improve health in the population of family caregivers, it is important to understand how caregiving impacts sleep and the extent to which characteristics of both the caregiver and the care recipient are associated with sleep disturbance. Identifying modifiable risk factors for poor sleep may help identify potential areas for intervention to improve sleep and allow for better coping and less burden in the role of informal family caregiver. Thus, the purposes of this systematic review are to describe the prevalence and types of sleep problems experienced by caregivers and to summarize the risk factors associated with sleep disturbance in informal family caregivers of adults living with chronic or life-threatening illness.

Methods

Data Sources

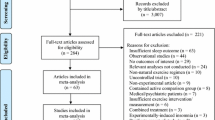

We searched PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and CINAHL databases for relevant literature using the keywords “sleep, insomnia, or circadian rhythm” and “caregiver or family.” In order to focus on recent research, articles in peer-reviewed journals between January 2013 and May 2016 were identified and then included if they were in the English language and involved adult participants. For inclusion in this analysis, articles were selected only if researchers met the following four criteria: (1) sampled caregivers of an adult family member, (2) examined sleep using subjective or objective measures, (3) reported on original data collected from caregivers, and (4) reported a factor affecting sleep or sleep as an outcome or dependent variable. We initially screened titles of articles from each search engine and selected articles potentially relevant to caregivers of adults or sleep in caregivers. After deleting duplicate articles, 148 articles remained and the abstracts were reviewed. After reviewing the 77 full-text articles that were unclear or potentially met inclusion criteria, a final set of 22 articles were eligible and included in this review [9–30].

Results

Study Sample Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the sample characteristics, sleep findings, and any factors associated with sleep for each article included in our review. The sample size of caregivers across studies ranged from 12 to 300 (median = 113, interquartile range = 113) [9–30]. The mean age of caregivers ranged from 40.7 ± 13.6 to 74.2 ± 7.9 years. Most caregivers were women, ranging from 43 to 90 % of the study samples. Most caregivers were spouses or partners (9 to 100 %) or adult children (6 to 86 %). Seven of the 22 articles reported race/ethnicity, and the majority of caregivers were White, ranging from 57 to 94 % [13, 20, 21, 23–25, 28] of the study samples. The most frequent illnesses represented by care recipients were dementia (including Alzheimer’s disease) [11, 13, 14•, 18, 22–25, 29•] and cancer [15•, 19, 26, 27, 30]. Other illnesses among care recipients included Parkinson’s disease [13], osteoarthritis of the knee [17•], primary malignant brain tumor [20], and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation [21]. Also included were family caregivers of patients who underwent peritoneal dialysis [9], hemodialysis [10], and renal transplantation [9, 10]; patients in intensive care units (ICUs) [12, 28]; and patients admitted to hospice [16]. The mean age of care recipients ranged from 53 to 85 years. Of the 22 published studies, 13 included the sex of care recipients and included both men and women [11, 14•, 15•, 16, 17•, 18–20, 22–23, 24•, 26, 27].

Study Measures of Sleep

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [31] was the most frequently used measure (14 of the 22 studies) to assess self-reported sleep quality in the past month [9, 10, 13, 15•, 16, 17•, 18, 20–25, 29•]. Three studies [11, 12, 26] used the General Sleep Disturbance Scale (GSDS) [32] to assess self-reported frequency of specific sleep problems during the past week. One study [28] used the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) to assess the likelihood of falling asleep in common daily situations [33] and the Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire–short form (FOSQ-10) [34] to assess impairment of daily activities due to sleepiness. Other studies [19, 27, 30] used the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) [35, 36], a questionnaire that assesses the severity of insomnia symptoms and how much caregivers were bothered by insomnia symptoms, and the Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) subscale related to sleep [37]. Two qualitative studies described caregivers’ sleep experiences using thematic analysis [14] or a phenomenological framework [24•].

Six studies used a wrist actigraph [15•, 16, 18, 22, 29•] or an accelerometer [20] device to obtain an objective measure of sleep parameters, such as total sleep time (TST), wake after sleep onset (WASO), daytime napping, sleep onset latency, and sleep efficiency. Two studies reported sleep–wake cycle variables such as bedtime and wake time [18, 20]. Participants in these six objective sleep studies wore the monitoring device from one night to longer than 2 weeks.

Self-Reported Sleep Among Caregivers

Poor sleep quality and sleep disturbance were the most frequent self-reported sleep problems described in the 22 studies. The mean PSQI scores among the 14 studies using this measure ranged from 2 to 9 on a scale of 0 to 21, and between 8 and 76 % (median = 52, interquartile range = 53) of caregivers reported PSQI global scores greater than 5, indicating poor sleep quality. The mean GSDS scores among the three studies using this measure ranged from 38 to 46. Between 31 and 39 % of caregivers of oncology patients reported significant sleep disturbance (scores above 43) [26], and 58 % of caregivers of ICU patients reported moderate to severe sleep disturbance [12].

Nearly half of caregivers for ICU patients experienced excessive daytime sleepiness based on a cut point of ≥10 on the ESS, and 62 % of caregivers experienced impairment in daily function due to daytime sleepiness [28]. Between 63 and 87 % of caregivers of patients with cancer reported insomnia [19, 27]; 30 % experienced moderate to severe insomnia symptoms [19]. Most caregivers for people with dementia believed that their sleep quality was poor, which was supported by the PSQI scores (mean = 6.8 ± 3.3) [24•]. Gibson and colleagues analyzed focus group data from 12 caregiver–patient dyads, and the following four common issues related to caregiver sleep emerged: being awakened at night, having problems getting back to sleep, trips to the bathroom for both patients and caregivers, and daytime sleepiness [14•].

Objective Sleep Among Caregivers

Actigraph-based TST for 24 h ranged from 6.3 to 8.1 h (median = 7.2) [15•, 16] and TST at night ranged from 4.6 to 8.1 h (median = 7.3, interquartile range = 1.4) [15•, 16, 18, 20, 22, 29•]. TST at night was shorter than 7 h in 30 % of caregivers of patients admitted to hospice [16]. The mean bedtime ranged from 22:37 p.m. ± 57 min to 23:04 p.m. ± 111 min and the mean wake time ranged from 6:45 a.m. ± 20 min to 7:14 a.m. ± 60 min in the two studies that reported on these times [18, 20].

Sleep maintenance was in a narrow range from 86 to 88 % of the time in bed [18, 29•], but the number of night awakenings fluctuated between 4 and 30 (median = 9, interquartile range = 23) [15•, 16, 18, 20], while minutes of WASO ranged from 8 to 112 (median = 64, interquartile range = 4.5) [16, 18, 22, 29•]. Due to wide variations in nocturnal sleep duration, WASO is often standardized as a percentage of the person’s time in bed after sleep onset (WASO%). WASO% ranged from 15 to 20 % (median = 18) [15•, 16, 20]. Half of the caregivers for patients admitted to hospice experienced sleep disruption based on WASO ≥15 % [16]. Other studies reported sleep onset latency that ranged from a mean of 7 to 35 min (median = 10) [15•, 20, 22], sleep efficiency that ranged from 91 to 98 % (median = 95) [15•, 22], and daytime nap duration that ranged from 16 to 101 min (median = 28) [15•, 16, 20]. The variability in sleep onset latency and daytime napping in these samples of caregivers for a patient with cancer, malignant brain tumor, or dementia is typical of most studies regardless of the population.

Factors Associated with Sleep Disturbance

Caregiver Characteristics

Several caregiver demographic factors were associated with poor sleep. Compared to men, women caregivers reported poorer sleep quality [15•, 29•], worse sleep disturbance [26], and more impairment in daily function due to daytime sleepiness [28]. Simpson and Carter also reported that gender was associated with sleep quality [23]. In critical care situations, the older the caregiver, the higher the functional impairment due to sleepiness [28]. The type of relationship between the care recipient and the caregiver was associated with sleep disturbance. Once a patient was admitted to hospice, their spouse or partner experienced less sleep disruption (WASO% and WASO minutes) than other family caregivers [16]. In a longitudinal sample of 278 family caregivers for a patient with cancer, female spouses or partners experienced worse sleep disturbance than male spouses or partners, yet it was other family caregivers who reported more sleep disturbance than a spouse or partner when they distinguished other family caregivers from spouse or partner caregivers [26]. In addition to sex, the caregiver’s employment status was also associated with sleep disturbance in some studies. In an early or advanced stage of cancer, caregivers who were unemployed reported more sleep disturbance than employed caregivers [15•, 26]. Unemployed caregivers of patients with a malignant brain tumor had higher WASO [20] than employed caregivers. For caregivers of patients in an early phase of cancer, employed males had worse sleep than employed females and employed spouse/partner caregivers had worse sleep than other employed family caregivers [26].

Other caregiver characteristics associated with poor sleep quality include increased role overload [29•] and lack of support [15•]. Unexpectedly, caregivers with higher self-esteem experienced poorer sleep quality [15•]. These caregivers may have high expectations regarding their caregiving responsibility and experience high stress, which may have increased their level of sleep disturbance [15•]. In one study, caregivers with more roles (e.g., caring for children, working, and volunteering) had better sleep quality and less depression [25]. The caregiver’s living situation may also be associated with sleep disturbance. Although self-reported sleep quality was found to be similar in caregivers who lived with, or separate from, their family member with dementia, the caregivers who lived with the care recipient reported more frequent sleep disruptions at night [25]. When caregivers had a family member in an adult medical–surgical ICU, those who did not live with the patient prior to admission reported worse sleep than those who did live with the patient, and caregivers who spent at least one night at the hospital reported worse sleep than those who never slept in the hospital [12].

Caregiver Symptom Experience and Health Status Associated with Sleep

Depression was the symptom most frequently associated with self-reported sleep disturbance [11] and poor sleep quality [13, 17•, 23]. The use of antidepressant medication was associated with longer sleep duration for the caregivers of spouses with Alzheimer’s disease [29•]. Anxiety was also associated with both self-reported sleep disturbance [12] and poor sleep quality [20]. However, in a sample of primarily female spousal caregivers for malignant brain tumor patients, anxiety was associated with longer TST and lower WASO, as measured by three nights of actigraphy [20]. Fatigue was also associated with self-reported sleep disturbance [11, 12]. Qualitative data from family caregivers of people with dementia indicated that poor mood (including worry and depression) was related to their sleep problems, and while they felt physically and mentally exhausted by bedtime, they still had problems falling asleep [14•].

Sleep quality was associated with the caregiver’s own health status [15•] and self-reported healthy behaviors [21]. Self-reported sleep disturbance was related to current poor health status of caregivers of a spouse with cancer [30]. As in most populations, higher body mass index (BMI) was associated with more WASO and reduced sleep percentage in caregivers of spouses with Alzheimer’s disease [29•]. Shorter sleep time was also associated with more health problems for these caregivers. During sleep, sympathetic nervous system activity measured with heart rate variability was higher in caregivers of a family member with dementia than in noncaregivers, especially for the first half of their sleep period [22].

Other Psychosocial Factors

Caregiver distress was associated with poor sleep quality [15•, 21], sleep disruption [18], and insomnia [19]. Caregivers with better coping skills had less disturbed sleep [30]. Positive affect (e.g., excited, proud, and active) was associated with better sleep quality [29•], whereas negative affect [17•] and burden [21] were associated with poor sleep quality. Fredman and colleagues compared older adult caregivers and noncaregivers [13]. PSQI scores did not differ between these two groups, but when they categorized the sample by depression scores on the CES-D, caregivers with high positive affect (feeling of psychological well-being) reported significantly better sleep quality scores on the PSQI than caregivers with negative affect, although this association was no longer statistically significant after adjusting for age, gender, education, number of medical conditions, and physical activity [13].

Care Recipient Factors

Nighttime dementia-related behaviors often disrupt a caregiver’s sleep [14•], and poor sleep quality is common among these caregivers [18]. Agitation and apathy in people with dementia were associated with poor sleep quality for the caregiver [23], and their sleep quality fluctuated with the cognitive status of the family member with dementia [24•]. Behavior problems in people with dementia were associated with poor sleep quality and more WASO in their caregivers [29•].

Physical function of adults with brain tumors was associated with the caregiver’s objective actigraphy sleep measures; care recipients with higher physical function had caregivers with longer TST, while care recipients with lower physical function had caregivers with higher WASO [20].

The care recipient’s sleep quality from the previous day was associated with caregiver sleep quality in a sample of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee and their caregivers [17•]. Among caregivers of patients with cancer, shorter period of time after diagnosis of cancer was associated with poorer sleep quality for the caregiver [15•] and mixed treatments for cancer were associated with worse sleep disturbance in caregivers than single modes of treatment [30].

The worse the health status of patients in adult medical–surgical ICUs, the worse the caregiver’s self-reported sleep disturbance on the GSDS [12]. In addition, caregivers for patients who were transferred to the ICU from another location in the hospital or from another hospital reported worse sleep disturbance than caregivers of a patient transferred from home [12].

Discussion

Our systemic review of the recent literature examining sleep and associated factors in caregivers showed that most caregivers reported poor sleep quality. Self-reported sleep disturbance in caregivers was also highly prevalent. Caregivers often reported sleep disruption, particularly caregivers of persons with dementia due to dementia-related behaviors in their care recipients. Caregivers of critically ill patients experienced excessive daytime sleepiness and impairment of daily activities due to sleepiness. Caregivers of cancer patients often reported insomnia. Data from actigraphy monitoring indicated short sleep duration, frequent nocturnal awakenings, and sleep disruption (WASO) in caregivers. Caregivers of cancer patients and malignant brain tumor patients napped during the day. Caregiver characteristics, such as gender, age, relationship to the care recipient, and employment status, were associated with sleep disturbance, although the reported directions were not always consistent. Sleep disturbance in caregivers was also associated with the caregiver’s own health status, symptoms of depression, anxiety, and fatigue, as well as other psychosocial factors such as distress and burden. Sleep disturbance in caregivers was also influenced by care recipient factors such as hospital transitions, dementia-related behaviors, and worsening health status.

Female caregivers reported more sleep problems than male caregivers, although earlier studies of caregivers for patients with cancer and Alzheimer’s disease concluded that there was no sex difference in sleep disturbance [26, 38, 39]. These conflicting results may be related to measurement issues, as women are known to differ on self-reported sleep measures when comparing their responses to objective sleep measures [40].

The caregiver’s own health status was significantly associated with sleep disturbance [15•, 21, 30]. This would be of concern to clinicians but should also be a concern of researchers who may need to control for the health status and comorbidities of a caregiver when studying sleep parameters or testing interventions to improve sleep in this population. Compared to other types of family caregivers, female spouse caregivers may be older and caring for an even older spouse. They may be experiencing age-related sleep disturbances related to menopausal symptoms, placing them at even higher risk for sleep disturbance when caregiving becomes a family responsibility. Given that poor sleep quality is associated with cognitive problems [41, 42] and trouble sleeping is associated with poorer medication adherence in adults living with a chronic illness [43], sleep disturbance in caregivers may influence not only their caregiver role and daily function, but also their ability to administer medical regimens related to their health and the health of their family member. Thus, addressing health issues and sleep disturbance would be particularly important for female spouse caregivers.

Symptoms of depression, anxiety, and fatigue, as well as psychosocial distress and burden, were associated with a caregiver’s sleep disturbance in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. These symptoms and psychosocial issues are likely to co-occur with sleep disturbance, rather than cause sleep disturbance. Although symptom clusters in caregivers are not well studied, symptom clusters for pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression have been reported in cancer patients [44]. Symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbance closely relate to caregiver burden [2]. More tailored intervention strategies that treat and manage sleep disturbance with other concurrent symptoms in caregivers may help clinicians to maximize health outcomes. More frequent measures of these symptoms in longitudinal studies may be informative, yet most measures ask caregivers to respond while thinking about the past week or month, making it difficult to ascertain which symptom may have occurred first.

The care recipient’s health status was associated with the caregiver’s sleep disturbance [12]. Osteoarthritis-related knee pain [17•] and dementia-related behavior problems [14•, 18, 29•] in care recipients impacted the caregiver’s sleep. However, specific sleep locations for the dyad are not reported and would influence the extent of these associations. While laboratory sleep studies are typically single-bed polysomnography studies conducted without the bed partner, dyadic sleeping arrangements are not typically described in research studies in the home or in self-reported sleep measures. Researchers and clinicians seldom inquire about the dyad’s sleep location and whether there is bed sharing, room sharing, or separate bedrooms. For example, sleeping in the same bed may reduce the caregiver’s burden at night but may increase the potential for disturbed sleep. A dyadic approach to sleep data analysis may reveal how caregivers and patients influence each other’s sleep. Interventions for the dyad that included symptom management, coping effectiveness, and other components for patients with cancer and their caregivers improved coping, self-efficacy, and social quality of life for both caregiver and care recipient, and the caregiver’s emotional quality of life also improved [45]. Interventions targeting sleep disturbance for caregivers and for care recipients may provide synergetic effects in improving sleep in dyads.

Major limitations in the reviewed studies were the dominance of cross-sectional designs with small samples and either the lack of objective prospective sleep measures or the use of self-report measures that reference varying time frames from 1 week to 6 months. Three studies used longitudinal designs [17•, 26, 29•], and six studies assessed objective sleep using wrist actigraphy [15•, 16, 18, 22, 29•] or accelerometry [20]. Thus, more studies are needed to better understand how sleep quality changes over time for family caregivers and factors that influence their sleep even before therapy begins in addition to when the care recipient is undergoing treatment as well as a recovery period.

Although researchers have validated actigraphy with polysomnography measures of sleep and wake time for healthy adults and disturbed sleepers [46–48], actigraphy does not allow assessment of sleep stages. Polysomnography data indicate shorter TST, poorer sleep efficiency [49], more stage N1 sleep, and less stage R [50] in caregivers of a family member with dementia compared to noncaregivers. Further research with polysomnography would yield a better understanding of altered sleep in caregivers but would be less likely to consider aspects of daytime sleep or sleep pattern variability in the home caregiving environment.

Only two studies included aspects of circadian sleep–wake phase or circadian rhythm in caregivers by reporting bedtime and wake-up time for the sample [18, 20]. Overall, bedtimes and wake times were highly variable. Caregiving burden may be worsened or improved by compatible dyad bedtimes and final wake times. Studies that include chronotype of the caregiver and care recipient would be informative and necessary when formulating potential intervention strategies for the family.

Four studies reported on sleep medication use [13, 18, 21, 23], and two other studies reported PSQI use of sleep medication subscale scores [15•, 16]. One study was specific to antidepressant effects on caregiver sleep [29•]. Caregivers may not accept pharmacologic interventions if they feel that they must remain vigilant or fear that they will not awaken easily when needed by the care recipient. Caregivers of dementia patients reported that they slept lightly to assist their family member and assess their safety during the night [24•]. However, despite their awareness of poor sleep, these caregivers had not pursued or received assistance from clinicians [24•]. Clinicians should be sensitive to a caregiver’s complaints of poor sleep and provide tailored interventions based on each individual’s needs; this would improve sleep in this population.

Finally, 17 of the 22 studies in this systematic review focused on sleep in caregivers for persons with dementia or cancer. Further studies focusing on caregivers of family members with other types of acute and chronic illnesses, such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, and HIV/AIDS infection, would be informative and important for clinical practice.

Some limitations of this systematic review should also be considered. We only included articles published from 2013 to 2016. Studies published before 2013 may have captured other important findings regarding the impact of caregiving on sleep. The study samples of caregivers were heterogeneous with respect to type of caregiving and relationship to the care recipient. The care recipients were also diverse, crossing many diseases and stages of illness. As in our systematic review, others have also reported inconsistent factors affecting sleep in caregivers of people with dementia and cancer [6••, 7••]. Thus, our results should also be interpreted with caution in light of the heterogeneous samples of caregivers in our review.

In summary, caregivers’ experiences of poor sleep quality and sleep disturbance are highly prevalent. Objective sleep measures indicate short sleep durations, multiple nocturnal awakenings, and substantial sleep disruption (WASO). In addition to the care recipient’s health status, we found that the caregiver’s gender, age, relationship to the care recipient; status of employment; health status; and symptoms such as depression, fatigue, and anxiety were associated with sleep disturbance in caregivers. These characteristics may help clinicians identify caregivers at highest risk for developing sleep disturbance and in need of additional support. More research is needed to better understand when during the patient’s illness trajectory, more caregiver support is most beneficial, how chronotype or bedtimes and final wake times can affect caregiver burden and sleep quality, and when pharmacologic intervention for the caregiver may be beneficial or harmful to the caregiving process. Developing targeted interventions for both caregivers and care recipients at specific time points may improve sleep for the dyad as well as for the entire family and help prevent adverse health outcomes related to sleep disturbance.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. Caregiving in the U.S. 2009. http://www.caregiving.org/data/Caregiving_in_the_US_2009_full_report.pdf (2009). Accessed 5 Jul 2016.

Byun E, Evans LK. Concept analysis of burden in caregivers of stroke survivors during the early poststroke period. Clin Nurs Res. 2015;24(5):468–86.

Joling KJ, van Marwijk HWJ, Veldhuijzen AE, van der Horst HE, Scheltens P, Smit F, et al. The two-year incidence of depression and anxiety disorders in spousal caregivers of persons with dementia: who is at the greatest risk? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(3):293–303.

Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA. 1999;282(23):2215–9.

Haley WE, Roth DL, Howard G, Safford MM. Caregiving strain and estimated risk for stroke and coronary heart disease among spouse caregivers: differential effects by race and sex. Stroke. 2010;41(2):331–6.

•• Peng HL, Chang YP. Sleep disturbance in family caregivers of individuals with dementia: a review of the literature. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2013;49(2):135–46. 12p. This article reviewed 18 articles regarding health outcomes and factors associated with sleep disturbance in caregivers of individuals with dementia. Factors associated with sleep disturbance were caregiver’s depression, psychological distress, demographic factors (e.g., age), and care recipient’s conditions and behaviors. Health outcomes related to sleep disturbance included poor mental and physical health, reduced quality of life, and elevated coagulation and inflammation levels.

•• Kotronoulas G, Wengstrom Y, Kearney N. Sleep patterns and sleep-impairing factors of persons providing informal care for people with cancer: a critical review of the literature. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(1):E1–15. This article reviewed 17 articles that addressed sleep in caregivers of persons with cancer. Sleep problems included short sleep duration, nocturnal awakenings, wakefulness after sleep onset, and daytime dysfunction.

Carter PA. Caregivers’ descriptions of sleep changes and depressive symptoms. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29(9):1277–83.

Avsar U, Avsar UZ, Cansever Z, Set T, Cankaya E, Kaya A, et al. Psychological and emotional status, and caregiver burden in caregivers of patients with peritoneal dialysis compared with caregivers of patients with renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2013;45(3):883–6.

Avsar U, Avsar UZ, Cansever Z, Yucel A, Cankaya E, Certez H, et al. Caregiver burden, anxiety, depression, and sleep quality differences in caregivers of hemodialysis patients compared with renal transplant patients. Transplant Proc. 2015;47(5):1388–91.

Chiu YC, Lee YN, Wang PC, Chang TH, Li CL, Hsu WC, et al. Family caregivers’ sleep disturbance and its associations with multilevel stressors when caring for patients with dementia. Aging Ment Health. 2014;18(1):92–101.

Day A, Haj-Bakri S, Lubchansky S, Mehta S. Sleep, anxiety and fatigue in family members of patients admitted to the intensive care unit: a questionnaire study. Crit Care. 2013;17(3):R91.

Fredman L, Gordon SA, Heeren T, Stuver SO. Positive affect is associated with fewer sleep problems in older caregivers but not noncaregivers. Gerontologist. 2014;54(4):559–69.

• Gibson RH, Gander PH, Jones LM. Understanding the sleep problems of people with dementia and their family caregivers. Dementia (London). 2014;13(3):350–65. This study conducted three focus groups on community-dwelling pairs (patient and family caregiver). The study revealed the types of sleep problems experienced by the patients and their family caregivers. It also described how they view their own sleep and their partner’s sleep and the strategies they used to manage sleep.

• Lee KC, Yiin JJ, Lu SH, Chao YF. The burden of caregiving and sleep disturbance among family caregivers of advanced cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38(4):E10–8. This study assessed subjective and objective sleep in caregivers of patients with advanced cancer and identified caregiving burden risk factors for sleep disturbance.

Lerdal A, Gay CL, Saghaug E, Gautvik K, Grov EK, Normann A, et al. Sleep in family caregivers of patients admitted to hospice: a pilot study. Palliat Support Care. 2014;12(6):439–44.

• Martire LM, Keefe FJ, Schulz R, Stephens MAP, Mogle JA. The impact of daily arthritis pain on spouse sleep. Pain. 2013;154(9):1725–31. This study conducted observational in-person interviews over 18 months with patients who had osteoarthritis of the knee and their caregivers. The study indicated that patient knee pain on the previous day was associated with caregiver’s sleep quality and feeling less refreshed after sleep.

Merrilees J, Hubbard E, Mastick J, Miller BL, Dowling GA. Sleep in persons with frontotemporal dementia and their family caregivers. Nurs Res. 2014;63(2):129–36.

Morris BA, Thorndike FP, Ritterband LM, Glozier N, Dunn J, Chambers SK. Sleep disturbance in cancer patients and caregivers who contact telephone-based help services. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(4):1113–20. 8p.

Pawl JD, Lee S-Y, Clark PC, Sherwood PR. Sleep characteristics of family caregivers of individuals with a primary malignant brain tumor. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40(2):171–9.

Ross A, Yang L, Klagholz SD, Wehrlen L, Bevans MF. The relationship of health behaviors with sleep and fatigue in transplant caregivers. Psychooncology. 2016;25(5):506–12.

Sakurai S, Onishi J, Hirai M. Impaired autonomic nervous system activity during sleep in family caregivers of ambulatory dementia patients in Japan. Biol Res Nurs. 2015;17(1):21–8.

Simpson C, Carter P. Dementia behavioural and psychiatric symptoms: effect on caregiver’s sleep. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(21–22):3042–52.

• Simpson C, Carter P. Dementia caregivers’ lived experience of sleep. Clin Nurse Spec. 2013;27(6):298–306. This qualitative study (phenomenology) explored the causes of poor sleep identified by caregivers of patients with dementia, how caregivers manage sleep and caregiver perceptions of suggestions to improve sleep.

Simpson C, Carter P. The impact of living arrangements on dementia caregiver’s sleep quality. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2015;30(4):352–9.

Stenberg U, Cvancarova M, Ekstedt M, Olsson M, Ruland C. Family caregivers of cancer patients: perceived burden and symptoms during the early phases of cancer treatment. Soc Work Health Care. 2014;53(3):289–309.

Tanimukai H, Hirai K, Adachi H, Kishi A. Sleep problems and psychological distress in family members of patients with hematological malignancies in the Japanese population. Ann Hematol. 2014;93(12):2067–75. 9p.

Verceles AC, Corwin DS, Afshar M, Friedman EB, McCurdy MT, Shanholtz C, et al. Half of the family members of critically ill patients experience excessive daytime sleepiness. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40(8):1124–31. 8p.

• von Känel R, Mausbach BT, Ancoli-Israel S, Mills PJ, Dimsdale JE, Patterson TL, et al. Positive affect and sleep in spousal Alzheimer caregivers: a longitudinal study. Behav Sleep Med. 2014;12(5):358–72. This study was longitudinal (lasting up to 4 years) with caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. The study examined the relationship between positive affect and subjective and objective (using actigraphy) sleep and revealed that increased positive affect was associated with better sleep.

Zhang Q, Yao D, Yang J, Zhou Y. Factors influencing sleep disturbances among spouse caregivers of cancer patients in Northeast China. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e108614.

Buysse DJ, Reynolds 3rd CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213.

Lee KA. Self-reported sleep disturbances in employed women. Sleep. 1992;15(6):493–8.

Johns MW. Reliability and factor analysis of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1992;15(4):376–81.

Weaver TE, Laizner AM, Evans LK, Maislin G, Chugh DK, Lyon K, et al. An instrument to measure functional status outcomes for disorders of excessive sleepiness. Sleep. 1997;20(10):835–43.

Morin CM. Insomnia: psychological assessment and management. New York: Guilford Press; 1993.

Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2(4):297–307.

Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL). A measure of primary symptom dimensions. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry. 1974;7:79–110.

Aslan O, Sanisoglu Y, Akyol M, Yetkin S. Quality of sleep in Turkish family caregivers of cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 2009;32(5):370–7.

von Kanel R, Mausbach BT, Ancoli-Israel S, Dimsdale JE, Mills PJ, Patterson TL, et al. Sleep in spousal Alzheimer caregivers: a longitudinal study with a focus on the effects of major patient transitions on sleep. Sleep. 2012;35(2):247–55.

Castro CM, Lee KA, Bliwise DL, Urizar GG, Woodward SH, King AC. Sleep patterns and sleep-related factors between caregiving and non-caregiving women. Behav Sleep Med. 2009;7(3):164–79.

Byun E, Kim J, Riegel B. Associations of subjective sleep quality and daytime sleepiness with cognitive impairment in adults and elders with heart failure. Behav Sleep Med. 2016;26:1–16.

Byun E, Gay CL, Lee KA. Sleep, fatigue, and problems with cognitive function in adults living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2016;27(1):5–16.

Gay C, Portillo CJ, Kelly R, Coggins T, Davis H, Aouizerat BE, et al. Self-reported medication adherence and symptom experience in adults with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2011;22(4):257–68.

Illi J, Miaskowski C, Cooper B, Levine JD, Dunn L, West C, et al. Association between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine genes and a symptom cluster of pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and depression. Cytokine. 2012;58(3):437–47.

Northouse LL, Mood DW, Schafenacker A, Kalemkerian G, Zalupski M, LoRusso P, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a brief and extensive dyadic intervention for advanced cancer patients and their family caregivers. Psychooncology. 2013;22(3):555–63.

Ancoli-Israel S, Clopton P, Klauber MR, Fell R, Mason W. Use of wrist activity for monitoring sleep/wake in demented nursing-home patients. Sleep. 1997;20(1):24–7.

Cole RJ, Kripke DF, Gruen W, Mullaney DJ, Gillin JC. Automatic sleep/wake identification from wrist activity. Sleep. 1992;15(5):461–9.

Lichstein KL, Stone KC, Donaldson J, Nau SD, Soeffing JP, Murray D, et al. Actigraphy validation with insomnia. Sleep. 2006;29(2):232–9.

von Kanel R, Dimsdale JE, Ancoli-Israel S, Mills PJ, Patterson TL, McKibbin CL, et al. Poor sleep is associated with higher plasma proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 and procoagulant marker fibrin D-dimer in older caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(3):431–7.

Fonareva I, Amen AM, Zajdel DP, Ellingson RM, Oken BS. Assessing sleep architecture in dementia caregivers at home using an ambulatory polysomnographic system. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2011;24(1):50–9.

Acknowledgments

This review was supported by postdoctoral funding for Eeeseung Byun from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research (T32 NR007088) and the Academic Senate at UCSF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Eeeseung Byun, Anners Lerdal, Caryl L. Gay, and Kathryn A. Lee declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Women and Sleep

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Byun, E., Lerdal, A., Gay, C.L. et al. How Adult Caregiving Impacts Sleep: a Systematic Review. Curr Sleep Medicine Rep 2, 191–205 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40675-016-0058-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40675-016-0058-8