Abstract

Purpose of review

Exercise therapy is the first line treatment for patients with knee and hip osteoarthritis (OA) but is consistently underutilized. In this review, we aim to provide health care professionals with an overview of the latest evidence in the areas of exercise therapy for OA, which can serve as a guide for incorporating the ideal exercise therapy prescription in the overall management plan for their patients with OA.

Recent findings

Evidence continues to be produced supporting the use of exercise therapy for all patients with knee or hip OA. Ample evidence exists suggesting exercise therapy is a safe form of treatment, for both joint structures and the patient overall. Several systematic reviews show that exercise therapy is likely to improve patient outcomes, regardless of disease severity or comorbidities. However, no single type of exercise therapy is superior to others.

Summary

Health care practitioners and patients should be encouraged to incorporate exercise therapy into treatment plans and can be assured of the safety profile and likelihood of improvement in important patient outcomes. Since no single exercise therapy program shows vastly superior benefit, patient preference and contextual factors should be central to the shared decision-making process when selecting and individualising appropriate exercise therapy prescriptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

No cure for osteoarthritis (OA) is currently available. Therefore, treatment is primarily aimed at symptomatic control and reducing functional decline [1]. All major international treatment guidelines recommend exercise therapy as first line treatment for OA of the knee, hip, and hand, [2,3,4,5,6,7] including the recently updated guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (United Kingdom) [8••] and American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons [9••]. This recommendation is based on evidence from more than 80 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) performed over the last 40 years [10].

Unfortunately, multiple international datasets show that exercise therapy (and non-surgical/non-pharmacological treatments at large) remain an underutilized management tool for most people with knee and hip OA [11,12,13,14,15,16]. This may be due in part to beliefs amongst clinicians that people with OA will ultimately require a total joint replacement, despite most also acknowledging exercise therapy is indicated for OA and is well-supported by data [14] and some patients expressing a need for exercise-based interventions [17]. It is also common for patients to believe exercise will further damage their joint and lead to increased pain, therefore resulting in preferences for other treatment approaches that could replace lost or damaged articular cartilage [18]. Finally, system level barriers such as absent or inadequately funded programs and complex referral mechanisms also limit the usage of exercise interventions [19].

The objective of this narrative review is to provide health care professionals with an overview of the latest evidence in the areas of commonly asked questions about exercise therapy and OA, which can serve as a guide for incorporating the ideal exercise therapy prescription in the overall management plan for their patients with OA. In this article, we focus on knee and hip OA, two of the most prevalent and disabling conditions globally [20] and where the majority of clinical OA research has been conducted [21]. We first present the evidence for exercise therapy as a core treatment for knee and hip OA, considering both the safety profile and clinical effectiveness. Next, we review which patients may benefit most (and which may not) from exercise therapy. Furthermore, we discuss how exercise therapy can impart benefits beyond OA and provide suggestions for how to self-manage OA long term, and finally, we highlight several OA exercise therapy programs offered around the world.

Is Exercise Therapy Safe for the Joint?

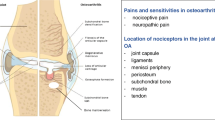

The knee joint includes several structures (e.g., menisci and ligaments) that can be affected by OA, with loss of articular cartilage being the hallmark of OA. It is a connective tissue that covers bone ends in the joints and provides lubrication of the meeting surfaces, allowing the transmission of loads with a low frictional coefficient [22]. The impact of exercise therapy specifically on knee joint articular cartilage, in people at risk of, or with knee OA has been summarised by two systematic reviews [23•, 24•]. The first systematic review focused on the impact of exercise therapy on articular cartilage assessed with MRI [23•] and the second focused on molecular biomarkers assessed via urine, blood and plasma samples [24•].

The first systematic review included nine RCTs including people who performed therapeutic exercise 1–5 times per week for 12–48 weeks. Articular cartilage assessed via MRI showed no harmful impact of exercise therapy on cartilage morphometry (i.e., thickness and volume), morphology (i.e., cartilage defects) and composition (i.e., glycosaminoglycans and collagen) [23•]. The second systematic review included 12 RCTs including people who performed aerobic or strength-based exercise therapy, or a combination of both, 2–5 times a week for 4–24 weeks. The findings of this systematic review showed that therapeutic exercise did not trigger inflammatory reactions (e.g., C-reactive protein and IL-6) nor increased the concentration of molecular biomarkers implicated in cartilage turnover (e.g., type II collagen carboxy propeptide and cartilage oligomeric matrix protein) [24•]. Additionally, another systematic review investigating the long-term effect of exercise therapy on other knee joint structures showed similar results [25]. No harmful effects on radiographic severity, cartilage morphology, or synovitis and effusion were found, but a slight increase in the likelihood of bone marrow lesion severity was observed [25].

Altogether, these systematic reviews highlight that beliefs about exercise therapy being harmful for articular cartilage and other knee joint structures are not supported by the available scientific evidence. People with OA must be reassured that exercise therapy seems not harmful to their knee joint. However, it is important to consider that the quality of the evidence in these systematic reviews were deemed low, suggesting that future trials may change the confidence we have in these results. Unfortunately, evidence about the impact of exercise therapy on hip OA are lacking.

Is Exercise Therapy Safe for the Patient?

Exercise therapy is a relatively safe intervention for many chronic conditions, as exercise therapy does not increase the risk of serious adverse events (e.g., hospitalization) but slightly increases the risk of non-serious adverse events (e.g., pain flares or muscle soreness which resolved without any additional treatment) [26]. This also applies to people with knee and hip OA. A 2015 systematic review of studies assessing exercise and physical activity interventions for people with knee OA/pain found no evidence of an increased risk of serious adverse events [27]. Likewise, moderate adverse events (i.e., significant enough to warrant a change in therapy) and minor adverse events (i.e., bothersome but not requiring a change in therapy) occurred in 0 to 6% and 0 to 22% of participants, respectively [27]. This finding of low numbers of adverse events were reinforced in two recent reviews of harms from exercise therapy for knee OA [28] and hip OA [29]. However, it is important to note that all three reviews call for improved reporting of adverse events in exercise therapy trials and there is need to investigate the safety of these interventions in different groups of patients with knee or hip OA, such as in those with comorbidity.

In addition to adverse events, patients often worry that exercise therapy (or physical activity in general) will cause progression or worsening of their OA [18]. As discussed above, exercise therapy seems not to have a detrimental effect on articular cartilage, but older studies have found conflicting evidence on the relationship between exercise therapy and risk of joint arthroplasty [30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. A recent study from the Osteoarthritis Initiative—a large prospective cohort study in the United States—investigating the association between walking (the most common form of exercise for patients with OA) and knee replacement in those with advanced disease found no increased risk of replacement surgery over 5 years [37]. Evidence of a protective effect against joint replacement was found with increased walking intensity (e.g. 37% reduction in risk of surgery when replacing 10 min per day of light walking with moderating walking intensity) [37]. Another analysis from the Osteoarthritis Initiative found those who walk for exercise are less likely to report new frequent knee pain (40% decreased odds) and medial joint space narrowing progression (20% decreased odds) [38]. Similar results were found in a large cohort study investigating the association between running or walking and total hip replacement [39] and a recent review found no evidence of worse imaging or clinical OA signs in elderly runners compared to non-runners [40]. Overall, clinicians can be confident when advising patients that exercise-based interventions have a high safety profile.

Is Exercise Therapy an Effective Treatment?

Several systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials have shown benefit for a variety of exercise therapy interventions, including strengthening, aerobic, and neuromuscular approaches for managing symptomatic hip and knee OA [41,42,43,44,45,46]. For example, in knee OA, a Cochrane systematic review including 54 individual RCTs reported small-to-moderate effect sizes of land-based exercise on pain (standardized mean difference (SMD) 0.49 [95% CI 0.39 to 0.59]), physical function (SMD 0.52 [95% CI 0.39 to 0.64]), and quality of life (SMD 0.28 [95% CI 0.15 to 0.40]) at end of treatment compared to non-exercise controls [43]. However, these effects were not sustained at medium-term (i.e., 2–6 months) or long-term (i.e., 6 months) follow-up. In hip OA, a Cochrane systematic review including 5 individual RCTs reported small-to-moderate effects on pain (SMD 0.30 [95% CI 0.10 to 0.49]) and physical function (SMD 0.35 [95% CI 0.13 to 0.57]) at end of treatment compared to non-exercise controls, and this effect was sustained for at least 2 to 6 months [42].

As highlighted above, there is an abundance of studies on exercise therapy for knee OA compared to hip OA, and the conclusion that exercise therapy is effective for managing knee OA symptoms is supported by sequential and cumulative meta-analyses suggesting that further trials are unlikely to overturn these results [41, 45]. However, as most RCTs have compared exercise to no-treatment controls [47••], the impact of placebo, contextual factors, and regression to the mean on effect estimates remains largely unknown. Consequently, comparative effectiveness trials have tested exercise against other clinically relevant treatments, including patient education and analgesics. A recent trial comparing exercise to a comprehensive attention control intervention (group-based educational sessions) found no significant difference in effects between interventions [48•]. This partly agrees with the findings from a systematic review by Goff et al. [49] showing that patient education is inferior to exercise in the short term (< 6 months) but produces similar medium-term (6 to < 12 months) and long-term (> 12 months) effects on pain. Despite oral paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs being the most commonly prescribed analgesics for management of OA symptoms, recent systematic reviews concluded that exercise produces either similar or significantly better effects on pain and function in patients with hip and knee OA [50•, 51•].

When tested against placebo interventions, exercise therapy may produce significantly larger reductions in pain but no difference in effect on physical function [52]. Contrarily, a recent trial comparing an exercise therapy and education intervention to intra-articular saline injections found no differences in effects on pain, physical function, or quality of life between interventions immediately after treatment [53•] or at 1-year follow-up [54]. However, as the placebo interventions were conceptually different from the active interventions, interpretation of effect estimates remains difficult. The importance of considering the type of comparator intervention when interpreting the effect of exercise for knee OA was recently demonstrated by Pedersen et al., [47••] showing that the effect of exercise for symptomatic knee OA varies significantly depending on the type of intervention applied in comparator groups, with large effects of exercise therapy compared to passive modalities and no-treatment controls, but a small effect of exercise therapy when compared to patient education/self-management. Finally, a recent network meta-analysis comparing all treatments for knee, hip, and hand OA concluded that exercise may be slightly more effective than no-intervention control and diet/weight loss for hip and knee OA, although there is only low-to-moderate confidence in these estimates [55•].

Which Patients do and do not Benefit from Exercise?

Although systematic reviews suggest, on average, small-to-moderate effects on pain, physical function, and quality of life, several studies have shown marked differences in individual patients’ treatment response [54, 56, 57]. However, recent efforts to identify potential treatment response moderators (i.e., characteristics that might impact patient response) of the effect of exercise therapy for knee OA have produced inconclusive or conflicting results. Few studies have attempted to identify moderators of the effect of exercise therapy for hip OA.

In a systematic review of moderators of the effects of exercise therapy for people with knee or hip OA, knee varus malalignment was identified as a moderator of the effect of exercise therapy on pain compared to a no-exercise control in people with knee OA, suggesting superiority of the exercise intervention in reducing pain compared to no-exercise control for people with neutral alignment but not in those with a varus malalignment [58]. Neither obesity, anxiety & depression, cardiac problems, diabetes, respiratory conditions, pain elsewhere, presence of comorbidity, number of comorbidities, or exercise confidence & beliefs moderated the pain treatment response, and none of the included variables moderated physical function treatment response [58]. A meta-analysis of individual participant RCT data suggested that knee and hip OA patients with higher baseline pain and physical function limitations may respond slightly better to exercise therapy compared to no-exercise controls [59••].

In a secondary analysis of an RCT comparing exercise therapy and patient education to intra-articular saline injections in people with knee OA, better treatment responses immediately after treatment (favoring the exercise interventions) were observed in participants who used analgesics compared to those who did not and for participants with constant knee pain at baseline [60]. Neither BMI, presence of a swollen knee, bilateral radiographic tibiofemoral OA, radiographic disease severity, activity level as a young adult, sex, age, treatment preference, or intermittent knee pain significantly moderated the treatment response [60]. Only those using analgesics had greater benefit at 1-year follow-up [54]. A register-based cohort study from the same patient education and exercise therapy program included 51 patient characteristics as potential predictors of individual changes in knee pain intensity, but were unable to identify any relevant predictors [61]. Similarly, multiple meta-regression analyses have been unable to identify any patient-level covariates impacting effect sizes of exercise therapy for knee OA [47••, 62]. However, a recent qualitative investigation, despite finding multiple shared characteristics between responders and non-responders, did find that non-responders perceived that high body weight, other health conditions, and life stressors that impacted exercise adherence contributed to a lack of response with exercise therapy [63].

Is there a Best Exercise Therapy for OA?

There is no single best exercise therapy prescription for knee or hip OA, in terms of specific exercise movement or technique, intensity level, or delivery method. While it might be attractive to have a single optimal exercise type, the available evidence highlights that the different types have comparable safety and effectiveness. Three systematic reviews have all found that no specific type of exercise (e.g., aerobic, strengthening, flexibility) is significantly superior for people with knee or hip OA [41, 62, 64]. Interestingly, mixed exercise programs (containing two different types of exercise) appear to be less effective than single-type programs, but the reasons for this are unclear [62, 64]. Aquatic exercise, another option for people with knee and hip OA, has been shown in multiple reviews to have similar effects when compared to land-based exercise [65,66,67].

Exercise intensity level or dose also does not seem to alter effectiveness. A 2015 Cochrane review found no difference in high- versus low-intensity exercise on pain or physical in the short- and long-term in people with knee or hip OA [68], and a 2017 review found exercise therapies designed according to the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) criteria for strength training are no more beneficial for knee pain or disability [69]. Conversely, a different 2017 review did find that ACSM compliant exercise programs were more effective for pain in people with hip OA, but not physical function [70]. Three recent reviews in people with knee OA have found no difference between high-intensity and low-intensity strength training on pain, function, and quality of life [71] and no benefit of ACSM compliant exercise therapies on pain or function [47••, 72]. Moreover, two recent trials in people with knee OA both found no benefit for high-intensity strength training over low-intensity training on pain or function [48•, 73], a third trial found no benefit when randomizing patients awaiting knee replacement to 2, 4 or 6 strength training sessions per week [74], and a fourth trial found no benefit when stratifying patients to high- or low-intensity exercise therapy (based on baseline muscle strength) compared to a usual exercise program [75]. These new trials raise further doubts about the benefits of increased exercise intensity levels or dose, especially for people with knee OA.

Remotely delivered exercise therapy programs are gaining popularity, especially since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. These exercise programs can be delivered via web or mobile applications, virtual and telehealth appointments, or in hybrid models. Remote delivery of exercise programs appears to have a similar effect on patient outcomes [76]. For example, in a large trial of Australian patients with knee OA and high body mass index (28 to 40 kg/m2), a telehealth exercise program and telehealth exercise and dietary intervention program both improved pain and function compared to usual care [77]. Likewise, a self-directed web-based strengthening program with automated behaviour-change text messages intervention improved pain and function compared to only information available on the web-based platform [78]. Despite some preconceived notions that exercise programs need to be delivered in-person, clinicians and patients report positive experiences with remote and hybrid delivery, although some do prefer more traditional methods of delivery [79, 80]. However, a review of mobile applications for chronic condition self-management, including exercise therapy, found apps for OA were the lowest quality and had the least potential for behaviour change when compared to other chronic conditions such as diabetes [81].

The exercise therapy interventions discussed above usually last 6 to 12 weeks. Therefore, the benefits gained from such interventions may dimmish over time, often due to the inability of the patient to continue exercising in the long-term. Therefore, educating patients about OA and how to self-manage the symptoms caused by OA is also a cornerstone for managing the condition [82]. The goal of self-management support is to teach problem solving skills related for their conditions in everyday life. This includes the ability to increase (or maintain) physical activity and continue exercising in the long-term. Although evidence for helping people self-manage in the long term is limited, the Behaviour Change Techniques ‘behavioural contract’, ‘non-specific reward’, ‘patient-led goal setting’ (behaviour), ‘self-monitoring of behaviour’, and ‘social support (unspecified) seems to be the most promising to promote physical activity in people with OA (Table 1) [83]. Mobile applications and other technologies may help support these efforts [84, 85]. However, a systematic review found that apps for OA have lower quality and potential for behaviour change compared to other chronic conditions [81]. Ongoing RCTs will improve understanding on the use of mobile applications in the management of OA [86].

Are the Benefits of Exercise Therapy Greater than just for OA?

Exercise therapy is a key treatment for 26 chronic conditions, including OA [87]. It has anti-inflammatory effects at cellular, tissue and organ levels and positive social, physical and physiological effects such as increases in muscle strength, improved blood pressure regulation and insulin sensitivity [88, 89]. This highlights that exercise therapy has an overall positive effect for the whole person and why exercise therapy seems to benefit people with several chronic conditions [90]. Two thirds of individuals with knee or hip OA live with an additional comorbidity, with common comorbidities including cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, diabetes, and depression [91]. This exacerbates pain and disability compared to those without comorbidities [92]. RCTs and observational studies suggest that exercise therapy improves health outcomes in people with OA and comorbidities [90, 93,94,95,96]. As an example, people with OA and type 2 diabetes mellitus improved to the same extent as people with OA and heart failure [94]. Additionally, despite people with OA and comorbidity having worse physical and mental health at baseline compared to people with only OA, similar levels of improvement after an exercise therapy intervention are attained [93]. These results suggest that exercise therapy may be a valid treatment option regardless of the comorbidity a person with OA experiences. Furthermore, exercise therapy can impart benefits beyond just knee and hip OA symptoms and impairments, including improvement in people’s mental, social and cardiovascular health [97].

What Exercise Therapy Programs Exist?

There are many OA management programs that include exercise therapy available around the world. Through the Arthritis Foundation (United States), patients can join the Walk with Ease program; a six week low-cost walking program aimed at making physical activity part of everyday life (https://www.arthritis.org/health-wellness/healthy-living/physical-activity/walking/walk-with-ease). Patients can complete the self-guided program on their own by following the guidebook or can join the group-based community walking program (where available). Both the self-directed and group-based options reduce arthritis pain and disability [98]. Also available from the Arthritis Foundation (in select communities across the country) are group-based exercise and aquatic exercise programs.

In Sweden, the Better Management of Patients with Osteoarthritis (BOA) program is a self-management education program with an optional exercise component [99]. The vast majority of patients choose to participate in the exercise component and outcomes show significant reductions in symptoms [100]. Another global program originating in Scandinavia, Good Life with osteoArthritis in Denmark (GLA:D®), is now offered in Australia, New Zealand, China, Switzerland, Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Ireland, and Canada [101]. GLA:D® is a group-based, but individualised program consisting of two patient education sessions and six weeks of neuromuscular exercise [102]. Clinical outcomes across countries have shown that patients have improved pain and function and use less pain medications (including opioids) after participating in GLA:D® [103,104,105].

There are also a number of remote/digital programs available that can improve access to exercise therapy for OA, especially during times of reduced in-person care like the COVID-19 pandemic or where geographical barriers exist. The Osteoarthritis Research Society International recently produced a repository of OA management programs including personalized exercise therapy (in combination with education and/or weight loss) that can be delivered in-person or remotely (https://www.keele.ac.uk/iau/oamps/) [106]. For example, the Enabling Self-Management and Coping with Arthritic Pain using Exercise (ESCAPE Pain; https://escape-pain.org/) [107, 108] in the United Kingdom and the Joint Academy program (based on the BOA program) in Sweden and the United States (https://www.jointacademy.com/us/en/) [109] offer structured exercise programs delivered via online applications. The Physiotherapy Exercise and Physical Activity for Knee Osteoarthritis (PEAK) program in Australia (https://healthsciences.unimelb.edu.au/departments/physiotherapy/chesm/clinician-resources/peak-training) includes five video consultations to support an education and exercise plan [110]. Freely available web-based resources like OA Optimism (https://www.oaoptimism.com/) also offer customizable exercise programs.

Conclusion

Exercise therapy should be considered a foundational aspect of treatment plans for all individuals with knee and hip OA. Both clinicians and patients can be assured of the safety profile of exercise therapy for both joint structures and clinical symptoms. Only a minority of patients experience minor and temporary increases in pain and emphasis should be made that increases in pain do not equate to serious harm or worsening OA. Likewise, ample trial evidence suggests that exercise therapy improves important outcomes like pain and function, regardless of patient characteristics like disease severity and the presence of other medical comorbidities.

While we have provided a summary of several aspects of exercise therapy prescription, we wish to stress that patient preference and contextual factors should be central to the selection of specific exercise therapy interventions. Not only is patient autonomy integral to patient-centred care and shared decision-making, but since there is no evidence for superiority of certain types of exercise or specific exercise therapy programs, clinicians should encourage the selection of exercise therapy interventions that are most preferable to the patient. Wider considerations like social determinants [111] and the built environment [112] are often an important aspect of management plans and should factor into exercise selection, such that the patient is able to select exercise therapy options that are enjoyable and feasible for their personal situation. Numerous available, and ever-increasing, digital and remote delivery options may help overcome barriers to exercise like geographic access and resource availability. We regard this more holistic approach to exercise therapy prescription to be of greater importance than any minute differences that might exist between different types of exercise therapy.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet. 2019;393:1745–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30417-9.

Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72:220–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.41142.

Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, Arden NK, Bennell K, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27:1578–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011.

Fernandes L, Hagen KB, Bijlsma JWJ, Andreassen O, Christensen P, Conaghan PG, et al. EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:1125–35. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202745.

Kloppenburg M, Bøyesen P, Smeets W, Haugen I, Liu R, Visser W, et al. Report from the OMERACT Hand Osteoarthritis Special Interest Group: Advances and Future Research Priorities. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:810–8. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.131253.

Nelson AE, Allen KD, Golightly YM, Goode AP, Jordan JM. A systematic review of recommendations and guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis: The Chronic Osteoarthritis Management Initiative of the U.S. Bone and Joint Initiative. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;43:701–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.11.012.

Oral A, Arman S, Tarakci E, Patrini M, Arienti C, Etemadi Y, et al. A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines for persons with osteoarthritis. A “Best Evidence for Rehabilitation” (be4rehab) paper to develop the WHO’s Package of Interventions for Rehabilitation. Int J Rheum Dis. 2022;25:383–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.14292.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Osteoarthritis in over 16s: diagnosis and management. 2022. This new clinical guideline provides the latest recommendations on the diagnosis and management of OA.

Brophy RH, Fillingham YA. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guideline Summary: Management of Osteoarthritis of the Knee (Nonarthroplasty), Third Edition. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2022;Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.5435/JAAOS-D-21-01233. This new clinical guideline provides the latest recommendations on the diagnosis and management of OA.

Kloppenburg M, Rannou F, Berenbaum F. What evidence is needed to demonstrate the beneficial effects of exercise for osteoarthritis? Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:451–3. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221685.

McHugh GA, Luker KA, Campbell M, Kay PR, Silman AJ. A longitudinal study exploring pain control, treatment and service provision for individuals with end-stage lower limb osteoarthritis. Rheumatology. 2006;46:631–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kel355.

Hofstede SN, Vliet Vlieland TPM, van den Ende CHM, Nelissen RGHH, Marang-van de Mheen PJ, van Bodegom-Vos L. Variation in use of non-surgical treatments among osteoarthritis patients in orthopaedic practice in the Netherlands. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e009117. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009117.

Hagen KB, Smedslund G, Østerås N, Jamtvedt G. Quality of community-based osteoarthritis care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68:1443–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.22891.

Briggs AM, Hinman RS, Darlow B, Bennell KL, Leech M, Pizzari T, et al. Confidence and attitudes toward osteoarthritis care among the current and emerging health workforce: a multinational interprofessional study. ACR Open Rheuma. 2019;1:219–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr2.1032.

King LK, Marshall DA, Faris P, Woodhouse LJ, Jones CA, Noseworthy T, et al. Use of recommended non-surgical knee osteoarthritis management in patients prior to total knee arthroplasty: a cross-sectional study. J Rheumatol. 2020;47:1253–60. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.190467.

Mazzei DR, Whittaker JL, Kania-Richmond A, Faris P, Wasylak T, Robert J, et al. Do people with knee osteoarthritis use guideline-consistent treatments after an orthopaedic surgeon recommends nonsurgical care? A cross-sectional survey with long-term follow-up. Osteoarthritis Cartilage Open. 2022;4:100256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocarto.2022.100256.

Papandony MC, Chou L, Seneviwickrama M, Cicuttini FM, Lasserre K, Teichtahl AJ, et al. Patients’ perceived health service needs for osteoarthritis (OA) care: a scoping systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25:1010–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2017.02.799.

Bunzli S, O’Brien BHealthSci (hons) P, Ayton D, Dowsey M, Gunn J, Choong P, et al. Misconceptions and the acceptance of evidence-based nonsurgical interventions for knee osteoarthritis. a qualitative study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2019;477:1975–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/CORR.0000000000000784.

Goff AJ, Donaldson A, de Oliveira SD, Crossley KM, Barton CJ. People with knee osteoarthritis attending physical therapy have broad education needs and prioritize information about surgery and exercise: a concept mapping study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2022;52:595–606. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2022.11089.

Safiri S, Kolahi A-A, Smith E, Hill C, Bettampadi D, Mansournia MA, et al. Global, regional and national burden of osteoarthritis 1990–2017: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:819–28. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216515.

Badley EM, Wilfong JM, Perruccio AV. Are we making progress? Trends in publications on osteoarthritis 2007–2016. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27:S278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2019.02.658.

Kim YJ, Bonassar LJ, Grodzinsky AJ. The role of cartilage streaming potential, fluid flow and pressure in the stimulation of chondrocyte biosynthesis during dynamic compression. J Biomech. 1995;28:1055–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9290(94)00159-2.

Bricca A, Juhl CB, Steultjens M, Wirth W, Roos EM. Impact of exercise on articular cartilage in people at risk of, or with established, knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:940–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-098661. This review of randomized controlled trials found exercise therapy does not appear to be harmful to articular cartilage based on MRI findings in people with knee OA.

Bricca A, Struglics A, Larsson S, Steultjens M, Juhl CB, Roos EM. Impact of exercise therapy on molecular biomarkers related to cartilage and inflammation in individuals at risk of, or with established, knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Care Res. 2019;71:1504–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23786. This review of randomized controlled trials found exercise therapy does not result in increased levels of molecular biomarkers associated with cartilage damage, inflammation, or OA progression.

Van Ginckel A, Hall M, Dobson F, Calders P. Effects of long-term exercise therapy on knee joint structure in people with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;48:941–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.10.014.

Niemeijer A, Lund H, Stafne SN, Ipsen T, Goldschmidt CL, Jørgensen CT, et al. Adverse events of exercise therapy in randomised controlled trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:1073–80. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-100461.

Quicke JG, Foster NE, Thomas MJ, Holden MA. Is long-term physical activity safe for older adults with knee pain?: a systematic review. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2015;23:1445–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2015.05.002.

von Heideken J, Chowdhry S, Borg J, James K, Iversen MD. Reporting of harm in randomized controlled trials of therapeutic exercise for knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2021;101:pzab161. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab161.

James KA, von Heideken J, Iversen MD. Reporting of adverse events in randomized controlled trials of therapeutic exercise for hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2021;101:pzab195. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzab195.

Manninen P, Riihimäki H, Heliövaara M, Suomalainen O. Physical exercise and risk of severe knee osteoarthritis requiring arthroplasty. Rheumatology. 2001;40:432–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/40.4.432.

Munugoda IP, Wills K, Cicuttini F, Graves SE, Lorimer M, Jones G, et al. The association between ambulatory activity, body composition and hip or knee joint replacement due to osteoarthritis: a prospective cohort study. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2018;26:671–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2018.02.895.

Wang Y, Simpson JA, Wluka AE, Teichtahl AJ, English DR, Giles GG, et al. Is physical activity a risk factor for primary knee or hip replacement due to osteoarthritis? A prospective cohort study. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:350–7. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.091138.

Leung YY, Razak HRBA, Talaei M, Ang L-W, Yuan J-M, Koh W-P. Duration of physical activity, sitting, sleep and the risk of total knee replacement among Chinese in Singapore, the Singapore Chinese Health Study. PLOS One. 2018;13:e0202554. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202554.

Johnsen MB, Hellevik AI, Baste V, Furnes O, Langhammer A, Flugsrud G, et al. Leisure time physical activity and the risk of hip or knee replacement due to primary osteoarthritis: a population based cohort study (The HUNT Study). BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:86. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-0937-7.

Ageberg E, Engström G, Gerhardsson de Verdier M, Rollof J, Roos EM, Lohmander LS. Effect of leisure time physical activity on severe knee or hip osteoarthritis leading to total joint replacement: a population-based prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13:73. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-13-73.

Skou ST, Wise BL, Lewis CE, Felson D, Nevitt M, Segal NA. Muscle strength, physical performance and physical activity as predictors of future knee replacement: A prospective cohort study. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2016;24:1350–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2016.04.001.

Master H, Thoma LM, Neogi T, Dunlop DD, LaValley M, Christiansen MB, et al. Daily walking and the risk of knee replacement over five years among adults with advanced knee osteoarthritis in the United States. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102:1888–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2021.05.014.

Lo GH, Vinod S, Richard MJ, Harkey MS, McAlindon TE, Kriska AM, et al. Association between walking for exercise and symptomatic and structural progression in individuals with knee osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022;74:1660–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.42241.

Williams PT. Effects of running and walking on osteoarthritis and hip replacement risk. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:1292–7. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182885f26.

Migliorini F, Marsilio E, Oliva F, Hildebrand F, Maffulli N. Elderly runners and osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2022;30:92–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/JSA.0000000000000347.

Uthman OA, van der Windt DA, Jordan JL, Dziedzic KS, Healey EL, Peat GM, et al. Exercise for lower limb osteoarthritis: systematic review incorporating trial sequential analysis and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f5555. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f5555.

Fransen M, McConnell S, Hernandez-Molina G, Reichenbach S. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the hip. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD007912. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007912.pub2.

Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, Van der Esch M, Simic M, Bennell KL. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015:CD004376. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004376.pub3.

Bartels EM, Juhl CB, Christensen R, Hagen KB, Danneskiold-Samsøe B, Dagfinrud H, et al. Aquatic exercise for the treatment of knee and hip osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016:CD005523. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005523.pub3.

Verhagen AP, Ferreira M, Reijneveld-van de Vendel EAE, Teirlinck CH, Runhaar J, van Middelkoop M, et al. Do we need another trial on exercise in patients with knee osteoarthritis? Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27:1266–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2019.04.020.

Hurley M, Dickson K, Hallett R, Grant R, Hauari H, Walsh N, et al. Exercise interventions and patient beliefs for people with hip, knee or hip and knee osteoarthritis: a mixed methods review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018:CD010842. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010842.pub2.

Pedersen JR, Sari DM, Juhl CB, Thorlund JB, Skou ST, Roos EM, et al. Variability in effect sizes of exercise therapy for knee osteoarthritis depending on comparator interventions. Ann Phys Rehabil 2023;66:101708. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2022.101708. This review of randomized controlled trials found the relative effectiveness of exercise therapy interventions is dependent on teh comparator intervention selected, raising concerns about the overall efficacy of exercise therapy for knee OA.

Messier SP, Mihalko SL, Beavers DP, Nicklas BJ, DeVita P, Carr JJ, et al. Effect of high-intensity strength training on knee pain and knee joint compressive forces among adults with knee osteoarthritis: the START randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021;325:646–57. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.0411. This randomized controlled trial found no difference between high-intensity exercise programs, low intensity exercise programs, and an attention control intervention, suggesting intensity is not an important parameter of exercise therapy interventions and raising questions about the overall efficacy of exercise therapy.

Goff AJ, De Oliveira SD, Merolli M, Bell EC, Crossley KM, Barton CJ. Patient education improves pain and function in people with knee osteoarthritis with better effects when combined with exercise therapy: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2021;67:177–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2021.06.011.

Thorlund JB, Simic M, Pihl K, Berthelsen DB, Day R, Koes B, et al. Similar effects of exercise therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and opioids for knee osteoarthritis pain: a systematic review with network meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2022;52:207–16. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2022.10490. This review of randomized controlled trials found no clinically meaningful differences between exercise therapy, non-steroidal anti-inflammatoriy drugs, and opioids for patients with knee OA, suggesting exercise therapy should be offered for knee OA.

Weng Q, Goh S-L, Wu J, Persson MSM, Wei J, Sarmanova A, et al. Comparative efficacy of exercise therapy and oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and paracetamol for knee or hip osteoarthritis: a network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med 2023. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2022-105898. This review of randomized controlled trials found comparable changes in patient-reported pain and function outcomes between exercise therapy, oral NSAIDs, and paracetamol, providing evidence that exercise therapy should be part of the standard treatment protocol for knee and hip OA.

Dean BJF, Collins J, Thurley N, Rombach I, Bennell K. Exercise therapy with or without other physical therapy interventions versus placebo interventions for osteoarthritis –Systematic review. Osteoarthr Cartil Open. 2021;3:100195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocarto.2021.100195.

Bandak E, Christensen R, Overgaard A, Kristensen LE, Ellegaard K, Guldberg-Møller J, et al. Exercise and education versus saline injections for knee osteoarthritis: a randomised controlled equivalence trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2021:annrheumdis-2021–221129. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221129. This open-label placebo randomized controlled trial found no difference between an education and exercise therapy program and a course of saline injections in people with knee OA, raising questions about the efficacy of exercise therapy.

Henriksen M, Christensen R, Kristensen LE, Bliddal H, Bartholdy C, Boesen M, et al. Exercise and education versus intra-articular saline for knee osteoarthritis: A 1-year follow-up of a randomized trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2023:Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2022.12.011.

Smedslund G, Kjeken I, Musial F, Sexton J, Østerås N. Interventions for osteoarthritis pain: A systematic review with network meta-analysis of existing Cochrane reviews. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage Open 2022;4:100242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocarto.2022.100242. This new review of randomized controlled trials provides estimates of comparative effectiveness for a range of interventions for knee and hip OA.

Jönsson T, Eek F, Ekvall-Hansson E, Dahlberg L, Dell’lsola A. Who responds to first-line interventions delivered in primary care? a responder - non-responder analysis on people with knee or hip osteoarthritis treated in Swedish primary cares. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2020;28:S466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2020.02.730.

Teirlinck CH, Verhagen AP, Reijneveld EAE, Runhaar J, van Middelkoop M, van Ravesteyn LM, et al. Responders to exercise therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:7380. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207380.

Quicke JG, Runhaar J, van der Windt DA, Healey EL, Foster NE, Holden MA. Moderators of the effects of therapeutic exercise for people with knee and hip osteoarthritis: A systematic review of sub-group analyses from randomised controlled trials. Osteoarthr Cartil Open. 2020;2:100113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocarto.2020.100113.

Holden MA, Metcalf B, Lawford BJ, Hinman RS, Boyd M, Button K, et al. Recommendations for the delivery of therapeutic exercise for people with knee and/or hip osteoarthritis. An international consensus study from the OARSI Rehabilitation Discussion Group. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2022:S1063458422008883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2022.10.009. This study provides the most up to date recommendations developed by an international working group of researchers for delivering an exercise therapy intervention for people with knee and hip OA.

Henriksen M, Nielsen SM, Christensen R, Kristensen LE, Bliddal H, Bartholdy C, et al. Who are likely to benefit from the Good Life with osteoArthritis in Denmark (GLAD) exercise and education program? An effect modifier analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2023;31:106–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2022.09.001.

Baumbach L, List M, Grønne DT, Skou ST, Roos EM. Individualized predictions of changes in knee pain, quality of life and walking speed following patient education and exercise therapy in patients with knee osteoarthritis – a prognostic model study. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2020;28:1191–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2020.05.014.

Juhl C, Christensen R, Roos EM, Zhang W, Lund H. Impact of exercise type and dose on pain and disability in knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:622–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.38290.

Hinman RS, Jones SE, Nelligan RK, Campbell PK, Hall M, Foster NE, et al. Why don’t some people with knee osteoarthritis improve with exercise? A qualitative study of responders and non-responders. Arthritis Care Res. 2023:Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.25085.

Goh S-L, Persson MSM, Stocks J, Hou Y, Welton NJ, Lin J, et al. Relative efficacy of different exercises for pain, function, performance and quality of life in knee and hip osteoarthritis: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2019;49:743–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01082-0.

Dong R, Wu Y, Xu S, Zhang L, Ying J, Jin H, et al. Is aquatic exercise more effective than land-based exercise for knee osteoarthritis? Medicine. 2018;97:e13823. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000013823.

Song J-A, Oh JW. Effects of aquatic exercises for patients with osteoarthritis: systematic review with meta-analysis. Healthcare. 2022;10:560. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10030560.

Xu Z, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Wen Y. Efficacy and safety of aquatic exercise in knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rehabil. 2022:02692155221134240. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692155221134240.

Regnaux J-P, Lefevre-Colau M-M, Trinquart L, Nguyen C, Boutron I, Brosseau L, et al. High-intensity versus low-intensity physical activity or exercise in people with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD010203. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010203.pub2.

Bartholdy C, Juhl C, Christensen R, Lund H, Zhang W, Henriksen M. The role of muscle strengthening in exercise therapy for knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis of randomized trials. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;47:9–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.03.007.

Moseng T, Dagfinrud H, Smedslund G, Østerås N. The importance of dose in land-based supervised exercise for people with hip osteoarthritis. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2017;25:1563–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2017.06.004.

Hua J, Sun L, Teng Y. Effects of high-intensity strength training in adults with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2022;Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000002088.

Guo X, Zhao P, Zhou X, Wang J, Wang R. A recommended exercise program appropriate for patients with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2022;13:934511. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.934511.

de Zwart AH, Dekker J, Roorda LD, van der Esch M, Lips P, van Schoor NM, et al. High-intensity versus low-intensity resistance training in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. 2022:02692155211073039. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692155211073039.

Husted RS, Troelsen A, Husted H, Grønfeldt BM, Thorborg K, Kallemose T, et al. Knee-extensor strength, symptoms, and need for surgery after two, four, or six exercise sessions/week using a home-based one-exercise program: a randomized dose–response trial of knee-extensor resistance exercise in patients eligible for knee replacement (the QUADX-1 trial). Osteoarthr Cartil. 2022;30:973–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2022.04.001.

Knoop J, Dekker J, van Dongen JM, van der Leeden M, de Rooij M, Peter WF, et al. Stratified exercise therapy does not improve outcomes compared with usual exercise therapy in people with knee osteoarthritis (OCTOPuS study): a cluster randomised trial. J Physiother. 2022;68:182–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2022.06.005.

McHugh CG, Kostic AM, Katz JN, Losina E. Effectiveness of remote exercise programs in reducing pain for patients with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review of randomized trials. Osteoarthr Cartil Open. 2022;4:100264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocarto.2022.100264.

Bennell KL, Lawford BJ, Keating C, Brown C, Kasza J, Mackenzie D, et al. Comparing video-based, telehealth-delivered exercise and weight loss programs with online education on outcomes of knee osteoarthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:198–209. https://doi.org/10.7326/M21-2388.

Nelligan RK, Hinman RS, Kasza J, Crofts SJC, Bennell KL. Effects of a self-directed web-based strengthening exercise and physical activity program supported by automated text messages for people with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:776. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0991.

Hinman RS, Nelligan RK, Bennell KL, Delany C. “Sounds a bit crazy, but it was almost more personal”: a qualitative study of patient and clinician experiences of physical therapist–prescribed exercise for knee osteoarthritis via Skype. Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69:1834–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23218.

Ezzat A, Kemp J, Heerey J, Pazzinatto M, Silva DDO, Dundules K, et al. Implementing telehealth-delivered group-based education and exercise for osteoarthritis during the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed-methods evaluation. J Sci Med Sport. 2022;25:S9-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2022.09.131.

Bricca A, Pellegrini A, Zangger G, Ahler J, Jäger M, Skou ST. The quality of health apps and their potential to promote behavior change in patients with a chronic condition or multimorbidity: systematic search in App Store and google Play. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2022;10:e33168. https://doi.org/10.2196/33168.

Kroon FP, van der Burg LR, Buchbinder R, Osborne RH, Johnston RV, Pitt V. Self-management education programmes for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD008963. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008963.pub2.

Willett M, Duda J, Fenton S, Gautrey C, Greig C, Rushton A. Effectiveness of behaviour change techniques in physiotherapy interventions to promote physical activity adherence in lower limb osteoarthritis patients: A systematic review. PLOS One. 2019;14:e0219482. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219482.

Thompson D, Rattu S, Tower J, Egerton T, Francis J, Merolli M. Mobile app use to support therapeutic exercise for musculoskeletal pain conditions may help improve pain intensity and self-reported physical function: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2023;69:23–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphys.2022.11.012.

Baroni MP, Jacob MFA, Rios WR, Fandim JV, Fernandes LG, Chaves PI, et al. The state of the art in telerehabilitation for musculoskeletal conditions. Arch Physiother. 2023;13:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40945-022-00155-0.

Hinman RS, Nelligan RK, Campbell PK, Kimp AJ, Graham B, Merolli M, et al. Exercise adherence Mobile app for Knee Osteoarthritis: protocol for the MappKO randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23:874. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-022-05816-6.

Pedersen BK, Saltin B. Exercise as medicine – evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25:1–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12581.

Wedell-Neergaard A-S, Lang Lehrskov L, Christensen RH, Legaard GE, Dorph E, Larsen MK, et al. Exercise-induced changes in visceral adipose tissue mass are regulated by IL-6 signaling: a randomized controlled trial. Cell Metab. 2019;29:844-855.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2018.12.007.

Gleeson M, Bishop NC, Stensel DJ, Lindley MR, Mastana SS, Nimmo MA. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:607–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3041.

Bricca A, Harris LK, Jäger M, Smith SM, Juhl CB, Skou ST. Benefits and harms of exercise therapy in people with multimorbidity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ageing Res Rev. 2020;63:101166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2020.101166.

Swain S, Sarmanova A, Coupland C, Doherty M, Zhang W. Comorbidities in osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Care Res. 2020;72:991–1000. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24008.

Calders P, Van Ginckel A. Presence of comorbidities and prognosis of clinical symptoms in knee and/or hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018;47:805–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.10.016.

Pihl K, Roos EM, Taylor RS, Grønne DT, Skou ST. Associations between comorbidities and immediate and one-year outcomes following supervised exercise therapy and patient education – A cohort study of 24,513 individuals with knee or hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2021;29:39–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2020.11.001.

Pihl K, Roos EM, Taylor RS, Grønne DT, Skou ST. Prognostic factors for health outcomes after exercise therapy and education in people with knee and hip osteoarthritis with or without comorbidities: a study of 37,576 patients treated in primary care. Arthritis Care Res. 2021;74:1866–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24722.

de Rooij M, van der Leeden M, Cheung J, van der Esch M, Häkkinen A, Haverkamp D, et al. Efficacy of tailored exercise therapy on physical functioning in patients with knee osteoarthritis and comorbidity: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res. 2017;69:807–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23013.

Young JJ, Kongsted A, Hartvigsen J, Roos EM, Ammendolia C, Skou ST, et al. Associations between comorbid lumbar spinal stenosis symptoms and treatment outcomes in 6,813 patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis following a patient education and exercise therapy program. Osteoarthritis Cartilage Open. 2022;4:100324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocarto.2022.100324.

Skou ST, Pedersen BK, Abbott JH, Patterson B, Barton C. Physical activity and exercise therapy benefit more than just symptoms and impairments in people with hip and knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2018;48:439–47. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2018.7877.

Callahan LF, Shreffler JH, Altpeter M, Schoster B, Hootman J, Houenou LO, et al. Evaluation of group and self-directed formats of the Arthritis Foundation’s Walk With Ease Program. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:1098–107. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20490.

Thorstensson CA, Garellick G, Rystedt H, Dahlberg LE. Better Management of Patients with Osteoarthritis: development and nationwide implementation of an evidence-based supported osteoarthritis self-management programme. Musculoskelet Care. 2015;13:67–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.1085.

Jönsson T, Eek F, Dell’Isola A, Dahlberg LE, Ekvall Hansson E. The Better Management of Patients with Osteoarthritis Program: outcomes after evidence-based education and exercise delivered nationwide in Sweden. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0222657. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222657.

University of Southern Denmark. GLA:D® Denmark Annual Report 2021. Odense, Denmark: 2022.

Skou ST, Roos EM. Good Life with osteoArthritis in Denmark (GLA:DTM): evidence-based education and supervised neuromuscular exercise delivered by certified physiotherapists nationwide. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18:72. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-017-1439-y.

Roos EM, Grønne DT, Skou ST, Zywiel MG, McGlasson R, Barton CJ, et al. Immediate outcomes following the GLA:D® program in Denmark, Canada and Australia. A longitudinal analysis including 28,370 patients with symptomatic knee or hip osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2021;29:502–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2020.12.024.

Barton C, Kemp J, Roos E, Skou S, Dundules K, Pazzinatto M, et al. Program evaluation of GLA:D® Australia: Physiotherapist training outcomes and effectiveness of implementation for people with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil Open. 2021:100175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocarto.2021.100175.

Thorlund JB, Roos EM, Goro P, Ljungcrantz EG, Grønne DT, Skou ST. Patients use fewer analgesics following supervised exercise therapy and patient education: an observational study of 16 499 patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis. Br J Sports Med. 2021;55:670–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-101265.

Quicke JG, Swaithes LR, Campbell LH, Bowden JL, Eyles JP, Allen KD, et al. The OARSI “joint effort initiative” repository of online osteoarthritis management programmes: an implementation rapid response during covid-19. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2021;29:S87–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2021.02.121.

Hurley MV, Walsh NE, Mitchell HL, Pimm TJ, Patel A, Williamson E, et al. Clinical effectiveness of a rehabilitation program integrating exercise, self-management, and active coping strategies for chronic knee pain: A cluster randomized trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1211–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.22995.

Hurley MV, Walsh NE, Mitchell H, Nicholas J, Patel A. Long-term outcomes and costs of an integrated rehabilitation program for chronic knee pain: A pragmatic, cluster randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:238–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20642.

Dahlberg LE, Grahn D, Dahlberg JE, Thorstensson CA. A web-based platform for patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: a pilot study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5:e5665. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.5665.

Hinman RS, Kimp AJ, Campbell PK, Russell T, Foster NE, Kasza J, et al. Technology versus tradition: a non-inferiority trial comparing video to face-to-face consultations with a physiotherapist for people with knee osteoarthritis. Protocol for the PEAK randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21:522. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03523-8.

Luong M-LN, Cleveland RJ, Nyrop KA, Callahan LF. Social determinants and osteoarthritis outcomes. Aging Health. 2012;8:413–37. https://doi.org/10.2217/ahe.12.43.

Bowden JL, Hunter DJ, Feng Y. How can neighborhood environments facilitate management of osteoarthritis: a scoping review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021;51:253–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.09.019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict Interest

JJY reports Postdoctoral Fellowship support from the Arthritis Society Canada and the Danish Foundation for Chiropractic Research and Post-graduate Education, outside the submitted work; and is a member of the leadership team (non-financial interest) for the GLA:D® International Network, a not-for-profit initiative hosted at the University of Southern Denmark aimed at implementing clinical guidelines for osteoarthritis and low back pain in clinical practice.

JRP has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

AB has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Young, J.J., Pedersen, J.R. & Bricca, A. Exercise Therapy for Knee and Hip Osteoarthritis: Is There An Ideal Prescription?. Curr Treat Options in Rheum 9, 82–98 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40674-023-00205-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40674-023-00205-z