Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated caregivers and school-aged children to adapt to ongoing changes and uncertainty. Understanding why some caregivers and school-aged children area able to adapt and others are not could be attributed to resilience. The relationships between caregiver or child resilience and socioeconomic status (SES) in the context of COVID-19 remain largely un-explored. Therefore, the purpose of this qualitative systematic review was to explore (1) what is currently known about the relationship between caregiver and child resilience in the context of COVID-19; and (2) the role of SES on caregiver or child resilience throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Four databases (i.e., MEDLINE, Scopus, PsycINFO, and CINAHL) were systematically searched, title/abstract and full-text screening were conducted, and 17 articles met the inclusion criteria (i.e., discussed resilience of caregivers/children during COVID-19, mean age of children between 7–10, primary research/grey literature, English), including 15 peer-reviewed and two grey literature sources. Thematic analysis revealed five themes: (1) the mitigating effects of child resilience; (2) overcoming the psychological toll of the pandemic; (3) the unknown relationship: caregiver and child resilience; (4) family functioning during COVID-19; and (5) the perfect storm for socioeconomic impacts. Results from this review provide the first synthesis of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the resilience of caregivers and school-aged children. Future research should conduct longitudinal data collection to understand the possible long-term impacts of the pandemic on these populations’ resilience. Understanding these impacts will be integral to assisting families in bouncing back from the long-lasting adverse circumstances caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since December of 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic and associated public health restrictions have disrupted life for everyone (World Health Organization, 2020). These public health restrictions have impacted the lives of children as schools have vacillated between in-person and remote learning, there has been prolonged social and physical isolation, and home environments have been altered by the changing working conditions of caregivers (Carroll et al., 2020; Loades et al., 2020; Maunula et al., 2021; Suarez-Lopez et al., 2021). School-aged children have experienced some of the greatest pandemic adversities stemming from the fluctuation of remote and in-person learning with closures of schools impacting approximately 94% of the world’s student population (United Nations, 2020). These vacillations between in-person and remote learning may have contributed to anxiety, depression, and behavioural problems in children (Fegert et al., 2020). Although many hypothesized that the COVID-19 pandemic would negatively impact the mental wellbeing of school-aged children, preliminary results from cross-sectional studies have varied (Duan et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2021; Marques de Miranda et al., 2020; Orgilés et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2020; Yeasmin et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). Using retrospective reports, Cost and colleagues (2021) found among a sample of 1,013 Canadian children and youth aged 6 to 18 years, 60–70% experienced declines in at least one mental health domain. Conversely, these authors also noted that the mental health of 19–31% of children did improve during the pandemic (Cost et al., 2021). These contradictory findings regarding children’s mental health during the pandemic have been documented in other studies, suggesting the effects of the pandemics on school-aged children are complex and nuanced based with emerging evidence indicating access to other social determinants of health plays a role as well (Abrams & Szefler, 2020; Maximum City, 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated existing inequities for families (Cusinato et al., 2020; Public Health Agency of Canada [PHAC], 2020). One such inequity is income, with reports that families with lower incomes have disproportionately experienced food insecurity, changes in working conditions, job losses, and heightened financial insecurities (Cusianto et al., 2020; Gallitto, 2020; Prime et al., 2020; SickKids, 2021). While the COVID-19 pandemic is still ongoing, research on previous pandemics demonstrated children exposed to economic hardships and traumatic events were more likely to experience anxiety, depression, and behavioural difficulties, with the effects extending years after the traumatic events occurred (Hawryluck et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2012). Moreover, income and financial strain have notable effects on overall family functioning. In a recent study on caregivers (n = 572) in the United States investigating family dynamics following economic hardships such as job and income losses, it was found that caregivers were more likely to report depressive symptoms, increased stress levels, and negative interactions with their children (e.g., increase in yelling between family members, parents quicker to lose temper) as compared to the control group (Kalil et al., 2020). Similar results were found in a study of caregivers (n = 223) in the United States by Chen and colleagues (2022) who investigated the experiences of families with school-aged children during the initial months of the pandemic. Low-income caregivers experienced more financial hardships due to the pandemic compared to their higher income counterparts. Conclusions from this study suggested that family income level impacts their ability to cope with pandemic-related challenges (Chen et al., 2022).

A family’s ability to cope when they have experienced a traumatic event, such as a pandemic, depends on their personal resources, mental health, and resilience (Bridgland et al., 2021; Coulombe et al., 2020; Cusinato et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). Resilience can be understood as a dynamic process in which psychosocial and environmental factors interact to enable an individual to survive, grow, and thrive during adversity (Crann & Barata, 2015; Munoz et al., 2017; Prime et al., 2020). Resilience is influenced by factors such as individual characteristics, self-regulation, self-concept, family conditions, and/or community supports that promote positive outcomes or reduce negative outcomes during challenging times (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005; Zolkoski & Bullock, 2012). Family conditions including caregiver flexibility, positive caregiver-child relationships, constructive parenting, and parental strength, have been identified as environmental factors that positively impact children’s resilience (Black & Lobo, 2008; Daks et al., 2020; Guruge et al., 2021; Torres Fernandez et al., 2013). In a recent review on family resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic, Gayatri and Irawaty (2021) reported higher family resilience was related to lower anxiety, stress, and depression symptoms among both caregivers and children (n = 165,515). Moreover, a review on parental resilience by Gavidia-Payne and colleagues (2015) concluded that resilience among parents resulted from the combination of family abilities and external factors (e.g., social support) in anticipating, perceiving, and responding to changing circumstances. The importance of family functioning and a caregiver’s ability to adapt to changing environments are necessary prerequisites for caregivers to be resilient. Despite what is known regarding factors influencing caregiver resilience (e.g., family functioning, ability to adapt), research is unclear on whether children’s resilience has been impacted throughout the pandemic. Moreover, while some authors have explored caregiver and child resilience in silo from one another (Caputi et al., 2021; Cusinato et al., 2020; Mariani Wigley et al., 2021), the relationship between a caregiver’s resilience and that of their children remains largely unexplored.

The pandemic has changed the lives of all school-aged children and their caregivers with many experiencing economic strain (Chen et al., 2022; Hawryluck et al., 2004; Kalil et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2012). Research is clear that experiencing adverse events, such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, is experienced differently by individuals and this may be in part to resilience (Bridgland et al., 2021; Coulombe et al., 2020; Cusinato et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021). While studies have examined resilience among caregivers or their children distinct independently (Caputi et al., 2021; Cusinato et al., 2020; Mariani Wigley et al., 2021), few studies explore caregiver and child resilience together and fewer still nuance the effects of the pandemic based on social determinants of health (e.g., income, financial strain, employment, etc.). Specifically, the PHAC (2020) has called for research examining the intersection of social determinants of health, and the associated direct and indirect impacts of familial and child resilience in the context of COVID-19. As such the purpose of this study is to fill that gap by (1) exploring what is currently known about the relationship between caregiver and child resilience in the context of COVID-19; and (2) examining the role of SES on caregiver or child resilience throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A qualitative systematic review was undertaken to collage and synthesize data from the included studies to determine the status of this body of knowledge (i.e., resilience and socioeconomic status [SES]; Paré et al., 2015). Through employing typical systematic review methodologies (per Cochrane’s guidelines), we are able to provide a narrative synthesis of findings, making trends among the studies clearer (Paré et al., 2015). Ethics approval was not required for this review as all data was publicly available.

Four databases (i.e., MEDLINE, Scopus, PsycINFO, and CINAHL) were searched in March 2022 using the constructs caregivers, children, resilience, and COVID-19Footnote 1 (see Appendix A for complete search strategy). Grey literature searches involved systematically searching through key governmental agencies (e.g., Public Health Canada, Statistics Canada, etc.) for sources related caregiver or child resilience in the context of COVID-19. After these searches were conducted, all articles were imported into Covidence systematic review software (2021) where screening was conducted independently by two reviewers. Inclusion criteria for this review included: (1) results discussed resilience in caregivers and/or children in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic; (2) mean age of children between 7 and 10 years; (3) article classified as primary research or grey literature; and (4) written in English. The age range of 7 to 10 years was selected to capture both junior (i.e., grades K-3) and senior (i.e., grades 4–6) elementary school-aged children, given the varying ages at which children begin and end elementary school in different countries worldwide (UNESCO, 2021). Given the purpose of qualitative systematic reviews, including review studies was deemed to be beyond the scope of the current review (Paré et al., 2015). Articles needed to be written in English due to the language capabilities of both authors. Title/abstract (n = 356) and full-text (n = 123) screening were conducted in succession using the eligibility criteria outlined above (see Appendix B for rationale for excluded articles). There were no discrepancies in screening by the two reviewers. If discrepancies did arise, the reviewers planned to meet to go over the article together in detail, discussing whether the article met the outlined inclusion criteria. A total of 15 peer-reviewed studies and 2 sources of grey literature were included in the final review (see Fig. 1 for PRISMA diagram; Page et al., 2020).

Data from all eligible articles were extracted onto a template co-designed by the research team. Extracted information included study authors, year of publication, country of origin, aims/purpose, sample size/demographics (i.e., age, gender/sex), methodology/theoretical grounding, analysis method, outcome measures, and important results (related to caregiver/child resilience or SES). No original data was modified (see Table 1 for full extraction chart).

Methods of Analyses

The goal of this review was to bring together findings from the included studies as such, both numerical and thematic analyses were undertaken. Numerical analysis was used to identify the nature, distribution, and extent of studies included in this review. Thematic analysis was employed to inform our understanding of the context, related constructs, and outcomes for resilience among caregivers and children, as well as their SES during the COVID-19 pandemic. Both analyses were completed independently by the two authors, following which results were compared. First, data were synthesized by charting and sorting material from the data extraction table according to key themes. For thematic analysis, inductive content analysis according to Patton (2005), was conducted whereby emerging themes were independently identified based on all research included. Afterwards, both researchers met to compare themes and an iterative process was employed wherein emergent themes were compared to ascertain if themes were common between the dyad and final decisions were agreed upon to resolve all themes. Together, both the numerical and thematic analysis produced information highlighting consistencies and differences across studies regarding the outcomes of interest while providing an overview of the current status of the literature regarding caregiver/child resilience and SES in the context of COVID-19.

Results

Numerical Analysis

The 17 studies included in this review represented 2,425 children (Mage = 8.23) and 8,252 caregivers (Mage = 40.79). While both mothers and fathers were represented in this analysis, the majority of caregivers (80.95%) were female. Additionally, ten countries were represented in this review (see Table 2 for a full summary).

Study Design

Of the 17 studies included, 13 were quantitative (Caputi et al., 2021; Cusinato et al., 2020; Dominguez-Alvarez et al., 2020; Laufer & Bitton, 2021; Lim et al., 2021; Mariani Wigley et al., 2021; Marzilli et al., 2021; Mikocka-Walus et al., 2021; Nasir et al., 2021; Romero et al., 2020; Russell et al., 2022; Sorkkila & Aunola, 2021; Touloupis, 2021), two were qualitative (Guruge et al., 2021; Koskela et al., 2020), one was a policy brief (Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2021), and one was a public health report (PHAC, 2020). The quantitative studies all used cross-sectional data collection except for Russel and colleagues (2022), who collected data at baseline and a 30-day follow-up. Two quantitative studies used retrospective data reports (Lim et al., 2021; Mactavish et al., 2021), and there were no control groups used in any of the quantitative studies. Phenomenology was used for both qualitative studies.

Outcome Measures

Caregiver resilience was measured using the CD-RISC (n = 8; Connor & Davidson, 2003), BRS (n = 2; Smith et al., 2008), and ARM (n = 2; Liebenberg & Moore, 2018), while child resilience was measured in three studies, all of which used the CYRM (Ungar & Liebenberg, 2011). Parental and/or family SES was conceptualized and measured in a variety of ways including: (1) parent education, family income, and family financial solvency to face daily overheads (Dominguez-Alvarez et al., 2020); (2) personal accounts of financial resources (Guruge et al., 2021; Koskela et al., 2020); (3) concern regarding financial situations due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Laufer & Bitton, 2021); (4) financial stability (Lim et al., 2021); (5) socioeconomic conditions (Nasir et al., 2021); (6) parental level of education, based on the average of the father’s and mother’s educational level, and family economic level, based on parent-report of family income (Romero et al., 2020); (7) COVID-19 financial stressors (Russell et al., 2022); unemployment and perceived family income (Sorkkila & Aunola, 2021); and (8) measuring the direct and indirect impacts of COVID-19 on health (PHAC, 2020).

Thematic Analysis

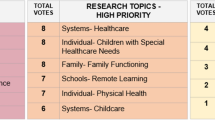

Thematic analysis revealed five themes related to child and caregiver resilience and SES included: (1) the mitigating effects of child resilience; (2) overcoming the psychological toll of the pandemic; (3) the unknown relationship: caregiver and child resilience; (4) family functioning during COVID-19; and (5) the perfect storm for socioeconomic impacts (for definitions of each theme see Table 3).

The Mitigating Effects of Child Resilience

A total of four studies examined child resilience and reported that childhood resilience reduced negative outcomes throughout the pandemic (Caputi et al., 2021; Cusinato et al., 2020; Dominguez-Alvarez et al., 2020; Mariani Wigley et al., 2021). Specifically, high resilience scores among children, based on the CYRM or parent-report, were associated with lower total difficulties, stress-related behaviours, and the impact of the pandemic on the overall wellbeing of children (Caputi et al., 2021; Cusinato et al., 2020; Mariani Wigley et al., 2021). Findings from these studies demonstrated children’s resilience reduced negative emotional symptoms, hyperactivity, conduct problems, and peer relationship problems (Caputi et al., 2021; Cusinato et al., 2020; Mariani Wigley et al., 2021). Furthermore, children high in resilience were more likely to engage in positive coping mechanisms responding to the pandemic, including active problem solving and seeking social support (Dominguez-Alvarez et al., 2020). Although authors from these studies only reported moderate resilience scores among their children, the benefits of resilience on mitigating pandemic-related outcomes were still found.

Overcoming the Psychological Toll of the Pandemic

Seven studies explored caregiver resilience and the psychological toll of the pandemic (Laufer & Bitton, 2021; Lim et al., 2021; Marzilli et al., 2021; Mikocka-Walus et al., 2021; Romero et al., 2020; Russell et al., 2022; Sorkkila & Aunola, 2021). Based on the overall depression, anxiety, and stress screens reported in these studies, it was evident caregivers experienced psychological distress throughout the pandemic (Laufer & Bitton, 2021; Lim et al., 2021; Marzilli et al., 2021; Mikocka-Walus et al., 2021; Romero et al., 2020; Russell et al., 2022). However, these studies reported caregiver resilience was negatively correlated to depression, anxiety, stress, and overall distress, making it likely that resilience among caregivers was an important factor in psychological toll of the pandemic. Given this relationship between resilience and psychological distress, it is unsurprising that resilience protected caregivers from burnout (Sorkkila & Aunola, 2021).

The Unknown Relationship: Caregiver and Child Resilience

Only two studies discussed the direct relationship between caregiver and child resilience and authors reported conflicting findings (Caputi et al., 2021; Mariani Wigley et al., 2021). Specifically, Caputi and colleagues (2021) noted a significant positive correlation between caregiver and child resilience (r = 0.49, p < 0.01) while Mariani Wigley and colleagues (2021) noted no significant correlation. As such, it remains unknown the relationship between caregiver and child resilience and the role it plays in the ability of families to adapt to ongoing changes during the pandemic.

Family Functioning during COVID-19

Nine studies examined factors contributing to overall family functioning during the COVID-19 pandemic including: supporting positive coping mechanisms, quality caregiver-child relationships, and family resilience (Caputi et al., 2021; Dominguez-Alvarez et al., 2020; Guruge et al., 2021; Koskela et al., 2020; Mariani Wigley et al., 2021; Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2021; Romero et al., 2020; Russell et al., 2022; Touloupis, 2021). Each of which will be discussed in turn.

Positive Coping Mechanisms

The importance of positive coping mechanisms among children (e.g., ability to regulate conduct and emotional problems) was positively correlated to caregiver resilience, with several studies addressing how caregivers can support these strategies in children (Dominguez-Alvarez et al., 2020; Romero et al., 2020; Russell et al., 2022). Supporting children to use positive coping mechanisms was found most commonly among caregivers high in resilience and low in psychological distress (Dominguez-Alvarez et al., 2020; Romero et al., 2020; Russell et al., 2022). Further, caregivers who taught positive coping mechanisms to children resulted in a positive correlation to children’s resilience (Mariani Wigley et al., 2021). Together, children employing positive coping strategies and caregivers and children being high in resilience led to lower stress-related behaviours among children and caregivers, thus improving family functioning during the pandemic.

Quality of Caregiver-Child Relationship

Despite the toll of the pandemic on families, the quality of family relationships had a positive impact on child development (Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2021). The quality of these relationships was noted as depending on support provided by caregivers, relationship closeness, and growth within caregiver-child relationships (Guruge et al., 2021; Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2021; Russell et al., 2022; Touloupis, 2021). These three aspects of family relationships were found to be positively related to caregiver resilience such that those caregivers high in resilience were able to provide higher quality relationships, resulting in benefits to child development (Guruge et al., 2021; Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2021; Russell et al., 2022; Touloupis, 2021).

Family Resilience

Family resilience, conceptualized as the ability for families to bounce back during the pandemic, was instrumental in family functioning. Families with high levels of resilience were better able to follow routines, use the resources available to them, adapt to changes, and find creative ways to problem solve – all of which contribute to families being positioned to thrive throughout the pandemic (Koskela et al., 2020).

The Perfect Storm for Socioeconomic Impacts

Ten studies highlighted how socioeconomic factors (e.g., income, employment) were impacted by the pandemic and that caregiver resilience played a role (Dominguez-Alvarez et al., 2020; Koskela et al., 2020; Laufer & Bitton, 2021; Lim et al., 2021; Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2021; Nasir et al., 2021; PHAC, 2020; Romero et al., 2020; Russell et al., 2022; Sorkkila & Aunola, 2021). The majority of caregivers were concerned about financial stability and reported psychological distress and behavioural issues among children (Laufer & Bitton, 2021; Lim et al., 2021; Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2021; PHAC, 2020). It was also reported that, compared to other adult populations, caregivers with school-aged children and those in lower-wage jobs faced a disproportionate rate of job losses (PHAC, 2020). The importance of access to external resources (e.g., flexible employers, financial support) was identified as essential to caregiver resilience (Koskela et al., 2020; Mental Health Commission, 2021). Family SES and the perceived economic impact of COVID-19 was noted by many as being a key factor determining caregivers’ resilience and the support they were able to provide to their children. Specifically, caregivers with high SES who perceived the economic impact of COVID-19 to be low reported higher resilience scores, were better able to support their children, and reported less psychological distress compared to caregivers with low SES (Dominguez-Alvarez et al., 2020; Nasir et al., 2021; Romero et al., 2020; Russell et al., 2022; Sorkkila & Aunola, 2021).

Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review was to (1) explore what is currently known about the relationship between caregiver and child resilience in the context of COVID-19; and (2) examine the role of SES on caregiver or child resilience throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Globally, children high in resilience are better able to reduce negative outcomes throughout the pandemic (e.g., stress-related behaviours, negative emotional symptoms, peer relationship problems). Further, high resilience among caregivers was a protective factor against psychological impacts of the pandemic on caregivers such as depression, anxiety, and stress. Despite these protective benefits, it remains unknown whether the interaction between both caregiver and child resilience have played a role in these groups independently and collectively adapting to ongoing fluctuations during the pandemic. What has been established is that family functioning throughout the pandemic was dependent upon positive coping mechanisms, the quality of caregiver-child relationships, and family resilience. Finally, the SES of many families was impacted throughout the pandemic and the perceived severity of this impact fluctuated depending on the resilience of caregivers.

Similar to the findings of this review that children’s ability to positively cope and be resilient is related to family functioning, Berger and colleagues (2021) reported that children are able to be resilient during infectious disease outbreaks when parents provide ongoing support. Regarding the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic however, Lateef and co-authors (2021) have highlighted the dearth of research on the consequences of pandemics on children and youth. Future research should focus on the long-term impacts of the pandemic on the resilience and overall well-being of children to ensure that future policy decisions are supporting children with what they need to bounce back from adversities.

The psychological toll that the pandemic has had on caregivers was also highlighted in the recent review of 29 articles by Lateef and colleagues (2021) who reported that caregivers were experiencing greater levels of psychosocial problems than adults without children. Given the abundance of evidence presented in the current review surrounding the relationship between these psychological problems and the resilience of caregivers, it is likely that the resilience of caregivers may have been impacted to a greater degree than their non-parent counterparts throughout the pandemic. Based on the heightened impact of the pandemic on the psychological wellbeing and resilience of caregivers, there is a need for future policy directions to focus on supporting caregivers immediately in future iterations of the pandemic to allow caregivers the additional assistance they need above and beyond other adults to move through adverse circumstances.

Similar to the findings of this review regarding the economic burden of the pandemic on families, Prime et al. (2020) found that low-income families and those with young children have been disproportionately impacted by loss of income. Financial stressors facing caregivers were noted to be common throughout the pandemic, including high rates of unemployment, the collapse of economic markets, and inadequate financial relief packages. These economic concerns coincided with other pandemic stressors (e.g., burden on caregivers to meet educational needs of children, change in work roles/routines), resulting in higher distress among caregivers and worse behavioural adjustment among children (Gallitto, 2020; Prime et al., 2020). Future research should investigate factors that could alleviate the economic burdens facing caregivers throughout the pandemic, paying particular attention to those families of low SES.

This study is the first systematic review synthesizing what is currently known about caregiver and child resilience and SES during the COVID-19 pandemic and revealed that resilience served as a protective factor against some negative impacts of the pandemic (e.g., stress-related behaviours, anxiety, depression, perceived economic impacts). While other reviews exist in this subject area, to the authors’ knowledge this is the first to review literature pertaining to the interaction between the resilience of both caregivers and young children. Moreover, this review is differentiated by others by taking into account the impacts of SES that may have been largely disrupted throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the findings of this review should be considered within the context of the limitations. The majority of the articles included in this review presented cross-sectional data limiting the ability to infer causation, accurately interpret associations, and evaluate the temporal relation between outcomes (Wang & Cheng, 2020). Given the varying ways in which economic impacts were experienced in different countries (e.g., high, middle, low income) throughout the pandemic, future research in this area should collect longitudinal data in each of these regions to provide a more fulsome picture of the economic impacts experienced by families during COVID-19. Some of the themes from this review were based on the limited number of studies that explored this topic (e.g., the unknown relationship: caregiver and child resilience; n = 2), which increases the potential of bias and therefore findings need to be cautiously interpreted and replicated in future studies. Finally, all of the data presented on child resilience is based on parent-report, despite validated scales existing that can measure resilience among this age demographic (e.g., True Resilience Scale for Children; Wagnild, 2009). As such, child resilience data is subject to implicit parental biases. Future studies should assess resilience from the perspective of children to provide a more accurate depiction of the pandemic’s impact on their resilience.

Conclusion

In the global context, this review revealed that the resilience of caregivers and their children, as well as family functioning – comprised of positive coping mechanisms, quality relationships, and family resilience – allowed families to be better able to overcome pandemic adversities. Moreover, families were better positioned to be resilient when they faced few economic hardships. Given these findings, resilience may be thought of as a ‘privilege’ that is easier to achieve when one has the resources in place to do so. Policymakers need to prioritize reducing the economic burden (i.e., job losses, financial strain) on families with young children to support families in dealing with already stressful situations. When families no longer need to worry about economic hardships, caregivers and children will be better equipped to be resilient through adverse times.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Notes

The Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) COVID-19 search string was used in each respective database to ensure all variations of COVID literature were included in the search results. These CADTH search strings were developed and peer-reviewed by Research Information Specialists and are continuously updated as new research emerges (CADTH, 2021).

References

Abrams, E. M., & Szefler, S. J. (2020). COVID-19 and the impact of social determinants of health. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8(7), 659–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30234-4

Ajanovic, S., Garrido-Aguirre, J., Baro, B., Balanza, N., Varo, R., Millat-Martinez, P., Arias, S., Fonollosa, J., Perera-Lluna, A., Jordan, I., Munoz-Almagro, C., Bonet-Carne, E., Crosas-Soler, A., Via, E., Nafria, B., Garcia-Garcia, J. J., & Bassat, Q. (2021). How did the COVID-19 lockdown affect children and adolescent’s well-being: Spanish parents, children, and adolescents respond. Frontiers in Public Health, 9(101616579), 746052. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.746052

Andres-Romero, M. P., Flujas-Contreras, J. M., Fernandez-Torres, M., Gomez-Becerra, I., & Sanchez-Lopez, P. (2021). Analysis of psychosocial adjustment in the family during confinement: Problems and habits of children and youth and parental stress and resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(101550902), 647645. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647645

Archer, J., Reiboldt, W., Claver, M., & Fay, J. (2021). Caregiving in quarantine: Evaluating the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on adult child informal caregivers of a parent. Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine, 7(101662571), 2333721421990150. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333721421990150

Ashikkali, L., Carroll, W., & Johnson, C. (2020). The indirect impact of COVID-19 on child health. Paediatrics and Child Health, 30(12), 430–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paed.2020.09.004

Asscheman, J. S., Zanolie, K., Bexkens, A., & Bos, M. G. N. (2021). Mood variability among early adolescents in times of social constraints: A daily diary study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(101550902), 722494. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.722494

Bates, C. R., Nicholson, L. M., Rea, E. M., Hagy, H. A., & Bohnert, A. M. (2021). Life interrupted: Family routines buffer stress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 9214438, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02063-6

Berger, E., Jamshidi, N., Reupert, A., Jobson, L., & Miko, A. (2021). Review: The mental health implications for children and adolescents impacted by infectious outbreaks—A systematic review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 26(2), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12453

Biden, E. J., Greenwood, C. J., Macdonald, J. A., Spry, E. A., Letcher, P., Hutchinson, D., Youssef, G. J., McIntosh, J. E., & Olsson, C. A. (2021). Preparing for future adversities: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia for promoting relational resilience in families. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12(101545006), 717811. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.717811

Black, K., & Lobo, M. (2008). A conceptual review of family resilience factors. Journal of Family Nursing, 14(1), 33–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840707312237

Bridgland, V. M. E., Moeck, E. K., Green, D. M., Swain, T. L., Nayda, D. M., Matson, L. A., Hutchinson, N. P., & Takarangi, M. K. T. (2021) Why the COVID-19 pandemic is a traumatic stressor. PLoS ONE 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240146

Brunelli, A., Silvestrini, G., Palestini, L., Vitali, P., Nanni, R., Belluzzi, A., Ciambra, R., De Logu, M., Degli Angeli, M., Dessi, F. L., Donati, D., Gaspari, L., Ghini, T., Giovannini, M., Iaia, M., Mazzini, F., Mollace, R., Nanni, V., Perra, A. P., & Marchetti, F. (2021). [Impact of the lockdown on children and families: A survey of family pediatricians within a community.]. Impatto Del Lockdown Sui Bambini e Sulle Famiglie: Un’indagine Dei Pediatri Di Famiglia All’interno Di Una Comunita., 112(3), 207–215. https://doi.org/10.1701/3565.35460

Bryson, H., Mensah, F., Price, A., Gold, L., Mudiyanselage, S. B., Kenny, B., Dakin, P., Bruce, T., Noble, K., Kemp, L., & Goldfeld, S. (2021). Clinical, financial and social impacts of COVID-19 and their associations with mental health for mothers and children experiencing adversity in Australia. PloS One, 16(9), e0257357. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0257357

CADTH. (2021). CADTH COVID-19 Search Strings. Retrieved September 23, 2021. https://covid.cadth.ca/literature-searching-tools/cadth-covid-19-search-strings/

*Caputi, M., Forresi, B., Giani, L., Michelini, G., & Scaini, S. (2021). Italian Children’s Well-Being after Lockdown: Predictors of Psychopathological Symptoms in Times of COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11429. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111429

Carroll, N., Sadowski, A., Laila, A., Hruska, V., Nixon, M., Ma, D. W. L., & Haines, J. (2020). The impact of COVID-199 on helath behaviour, stress, financial and food security among middle to high income Canadian families with young children. Nutrients, 12(2352). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12082352

Cauberghe, V., De Jans, S., Hudders, L., & Vanwesenbeeck, I. (2021). Children’s resilience during Covid-19 confinement. A child’s perspective-which general and media coping strategies are useful? Journal of Community Psychology, 0367033, huu, 0367033. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22729

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2020). COVID-19 in racial and ethnic minority groups. Retrieved October 1, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnicminorities.html

Chen, C.Y.-C., Byrne, E., & Vélez, T. (2022). Impact of the 2020 pandemic of COVID-19 on Families with School-aged Children in the United States: Roles of Income Level and Race. Journal of Family Issues, 43(3), 719–740. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X21994153

Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82.

Cost, K. T., Crosbie, J., Anagnostou, E., Birken, C. S., Charach, A., Monga, S., Kelley, E., Nicolson, R., Maguire, J. L., Burton, C. L., Schachar, R. J., Arnold, P. D., & Korczak, D. J. (2021). Mostly worse, occasionally better: Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01744-3

Coulombe, S., Pacheco, T., Cox, E., Khalil, C., Doucerain, M. M., Auger, E., & Meunier, S. (2020). Risk and Resilience Factors During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Snapshot of the Experiences of Canadian Workers Early on in the Crisis. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.580702

Covidence systematic review software. (2021). Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Retrieved September 1, 2021. www.covidence.org

Crann, S. E., & Barata, P. C. (2015). The experience of resilience for adult female survivors of intimate partner violence: A phenomenological inquiry. Violence against Women. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801215612598

Crescentini, C., Feruglio, S., Matiz, A., Paschetto, A., Vidal, E., Cogo, P., & Fabbro, F. (2020). Stuck outside and inside: an exploratory study on the effects of the COVID-19 outbreak on Italian parents and children’s internalizing symptoms. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(101550902), 586074. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586074

*Cusinato, M., Iannattone, S., Spoto, A., Poli, M., Moretti, C., Gatta, M., & Miscioscia, M. (2020). Stress, Resilience, and Well-Being in Italian Children and Their Parents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17228297

Daks, J. S., Peltz, J. S., & Rogge, R. D. (2020). Psychological flexibility and inflexibility as sources of resiliency and risk during a pandemic: Modeling the cascade of COVID-19 stress on family systems with a contextual behavioral science lens. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18(101616494), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.08.003

Davidson, B., Schmidt, E., Mallar, C., Mahmoud, F., Rothenberg, W., Hernandez, J., Berkovits, M., Jent, J., Delamater, A., & Natale, R. (2021). Risk and resilience of well-being in caregivers of young children in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 11(2), 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1093/tbm/ibaa124

*Dominguez-Alvarez, B., Lopez-Romero, L., Isdahl-Troye, A., Gomez-Fraguela, J. A., & Romero, E. (2020). Children Coping, Contextual Risk and Their Interplay During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Spanish Case. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(101550902), 577763. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577763

Duan, L., Shao, X., Wang, Y., Huang, Y., Miao, J., Yang, X., & Zhu, G. (2020). An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in china during the outbreak of COVID-19. Journal of Affective Disorders, 275, 112–118.

Eales, L., Ferguson, G. M., Gillespie, S., Smoyer, S., & Carlson, S. M. (2021). Family resilience and psychological distress in the COVID-19 pandemic: A mixed methods study. Developmental Psychology, 57(10), 1563–1581. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001221

Erdei, C., & Liu, C. H. (2020). The downstream effects of COVID-19: A call for supporting family wellbeing in the NICU. Journal of Perinatology : Official Journal of the California Perinatal Association, 40(9), 1283–1285. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-020-0745-7

Feng, Z., Xu, L., Cheng, P., Zhang, L., Li, L.-J., & Li, W.-H. (2020). The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the families of first-line rescuers. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 62(Suppl 3), S438–S444. https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_1057_20

Fegert, J. M., Vitiello, B., Plener, P. L., & Clemens, V. (2020). Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Mental Health, 14(20). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3

Fergus, S., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 399–419. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publichealth.26.021304.144357

Gallitto, E. (2020). Building resilience in children during the pandemic: The role of positive parenting. Interdisciplinary Research Laboratory on the Rights of the Child (IRLRC): University of Ottawa. Retrieved October 1, 2021. https://droitcivil.uottawa.ca/interdisciplinary-research-laboratory-rights-child/building-resilience-children-during-pandemic-role-positive-parenting

Gavidia-Payne, S., Denny, B., Davis, K., Francis, A., & Jackson, M. (2015). Parental resilience: A neglected construct in resilience research. Clinical Psychologist, 19(3), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/cp.12053

Gayatri, M., & Irawaty, D. K. (2021). Family resilience during COVID-19 pandemic: A literature review. The Family Journal. https://doi.org/10.1177/10664807211023875

Gibbons, J. L., Fernandez-Morales, R., Maegli, M. A., & Poelker, K. E. (2021). “Mi hijo es lo principal”—Guatemalan mothers navigate the COVID-19 pandemic. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 10(3), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1027/2157-3891/a000017

*Guruge, S., Lamaj, P., Lee, C., Ronquillo, C. E., Sidani, S., Leung, E., Ssawe, A., Altenberg, J., Amanzai, H., & Morrison, L. (2021). COVID-19 restrictions: Experiences of immigrant parents in Toronto. AIMS Public Health, 8(1), 172–185. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2021013

Hatzichristou, C., Georgakakou-Koutsonikou, N., Lianos, P., Lampropoulou, A., & Yfanti, T. (2021). Assessing school community needs during the initial outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic: Teacher, parent and student perceptions. School Psychology International, 42(6), 590–615. https://doi.org/10.1177/01430343211041697

Hawryluck, L., Gold, W. L., Robinson, S., Pogorski, S., Galea, S., & Styra, R. (2004). SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerging infectious diseases, 10(7), 1206–1212. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1007.030703

Herbert, J. S., Mitchell, A., Brentnall, S. J., & Bird, A. L. (2020). Identifying rewards over difficulties buffers the impact of time in COVID-19 lockdown for parents in Australia. Frontiers in Psychology, 11(101550902), 606507. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.606507

Hong, J. Y., Choi, S., & Cheatham, G. A. (2021). Parental stress of Korean immigrants in the U.S.: Meeting child and youth’s educational needs amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Children and Youth Services Review, 127(8110100), 106070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106070

Iovino, E. A., Caemmerer, J., & Chafouleas, S. M. (2021). Psychological distress and burden among family caregivers of children with and without developmental disabilities six months into the COVID-19 pandemic. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 114(8709782, rid), 103983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2021.103983

Johnson, M. S., Skjerdingstad, N., Ebrahimi, O. V., Hoffart, A., & Urnes Johnson, S. (2021). Mechanisms of parental distress during and after the first COVID-19 lockdown phase: A two-wave longitudinal study. PloS One, 16(6), e0253087. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253087

Jungmann, T., Heinschke, F., Federkeil, L., Testa, T., & Klapproth, F. (2021). Distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Level of stress and coping strategies of parents with school-age children. Zeitschrift Fur Entwicklungspsychologie Und Padagogische Psychologie, 53(3–4), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1026/0049-8637/a000241

Kalil, A., Mayerm S., & Shah, R. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 crisis on family dynamics in economically vulnerable households. Becker Friedman Institute, 143.

Kamran, A., & Naeim, M. (2021). Managing back to school anxiety during a COVID-19 outbreak. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 209(4), 244–245. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001313

Kim, I., Dababnah, S., & Lee, J. (2020). The influence of race and ethnicity on the relationship between family resilience and parenting stress in caregivers of children with autism. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 50(2), 650–658. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04269-6

Kohler-Dauner, F., Clemens, V., Hildebrand, K., Ziegenhain, U., & Fegert, J. M. (2021). The interplay between maternal childhood maltreatment, parental coping strategies as well as endangered parenting behavior during the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Developmental Child Welfare, 3(2), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/25161032211014899

*Koskela, T., Pihlainen, K., Piispa-Hakala, S., Vornanen, R., & Hämäläinen, J. (2020). Parents’ Views on Family Resiliency in Sustainable Remote Schooling during the COVID-19 Outbreak in Finland. Sustainability, 12(21), 8844. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12218844

Lateef, R., Alaggia, R., & Collin-Vezina, D. (2021). A scoping review on psychosocial consequences of pandemics on parents and children: Planning for today and the future. Children and youth services review, 125(106002). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106002

*Laufer, A., & Bitton, M. S. (2021). Parents’ Perceptions of Children’s Behavioral Difficulties and the Parent-Child Interaction During the COVID-19 Lockdown. Journal of Family Issues. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X211054460

Lawrence, K. C., Makhonza, L. O., & Mngomezulu, T. T. (2021). Assessing sources of resilience in orphans and vulnerable children in Amajuba District schools. South African Journal of Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1177/00812463211062771

Levine, C. (2020). Vulnerable children in a dual epidemic. The Hastings Center Report, 50(3), 69–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.1140

Liang, L., Ren, H., Cao, R., Hu, Y., Qin, Z., Li, C., & Mei, S. (2020). The effect of COVID-19 on youth mental health. Psychiatric Quarterly, 91(3), 841–852.

Liebenberg, L., & Moore, J. C. (2018). A social ecological measure of resilience for adults: The RRC-ARM. Social Indicators Research, 136(1), 1–19.

Li, F., Luo, S., Mu, W., Li, Y., Zheng, X., Xu, B., Ding, Y., Ling, P., Zhou, M., & Chen, X. (2021). Effects of sources of social support and resilience on the mental health of different age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry, 21(16). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-03012-1

*Lim, T. S. H., Tan, M. Y., Aishworiya, R., Kang, Y. Q., Koh, M. Y., Shen, L., & Chong, S. C. (2021). Correction to: Factors Contributing to Psychological Ill Effects and Resilience of Caregivers of Children with Developmental Disabilities During a Nationwide Lockdown During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 7904301, hgw. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05201-7

Liu, X., Kakade, M., Fuller, C. J., Fan, B., Fang, Y., Kong, J., Guan, Z., & Wu, P. (2012). Depression after exposure to stressful events: lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Comprehensive psychiatry, 53(1), 15–23. https://doi-org.proxy1.lib.uwo.ca/10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.02.003

Loades, M. E., Chatburn, E., Higson-Sweeney, N., Reynolds, S., Shafran, R., Brigden, A., Linney, C., McManus, M. N., Borwick, C., & Crawley, E. (2020). Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59, 1218–1239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009

Luthar, S. S., Ebbert, A. M., & Kumar, N. L. (2021). Risk and resilience during COVID-19: A new study in the Zigler paradigm of developmental science. Development and Psychopathology, 33(2), 565–580. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579420001388

Ma, Z., Idris, S., Zhang, Y., Zewen, L., Wali, A., Ji, Y., Pan, Q., & Baloch, Z. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic outbreak on education and mental health of Chinese children aged 7–15 years: An online survey. BMC Pediatrics, 21(1), 95.

Mactavish, A., Mastronardi, C., Menna, R., Babb, K. A., Battaglia, M., Amstadter, A. B., & Rappaport, L. M. (2021). Children’s Mental Health in Southwestern Ontario during Summer 2020 of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry = Journal de l’Academie Canadienne de Psychiatrie de l’enfant et de l’adolescent, 30(3), 177–190.

Marchetti, D., Fontanesi, L., Mazza, C., Di Giandomenico, S., Roma, P., & Verrocchio, M. C. (2020). Parenting-related exhaustion during the Italian COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 45(10), 1114–1123. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa093

*Mariani Wigley, I. L. C., Mascheroni, E., Bulletti, F., & Bonichini, S. (2021). COPEWithME: The role of parental ability to support and promote child resilient behaviours during the COVID-19 emergency. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.732745

Marques de Miranda, D., da Silva, A. B., Sena Oliveira, A., & Simoes-e-Silva, A. (2020). How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 51, 101845.

*Marzilli, E., Cerniglia, L., Tambelli, R., Trombini, E., De Pascalis, L., Babore, A., Trumello, C., & Cimino, S. (2021). The COVID-19 Pandemic and Its Impact on Families’ Mental Health: The Role Played by Parenting Stress, Parents’ Past Trauma, and Resilience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11450. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111450

Matiz, A., Fabbro, F., Paschetto, A., Urgesi, C., Ciucci, E., Baroncelli, A., & Crescentini, C. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on affect, fear, and personality of primary school children measured during the second wave of infections in 2020. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.803270

Maunula, L., Dabravolskaj, J., Maximova, K., Sim, S., Willows, N., Newton, A. S., & Veugelers, P. J. (2021). “It’s Very Stressful for Children”: Elementary School-Aged Children’s Psychological Wellbeing during COVID-19 in Canada. Children, 8(12). https://doi.org/10.3390/children8121185

Maximum City. (2021). COVID-19 child and youth well-being study: Canada Phase One Report. Retrieved September 23, 2021. https://maximumcity.ca/wellbeing

*Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2021, June 25). COVID-19 and early childhood mental health: Fostering system change and resilience policy brief. Health Canada. https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/resource/covid-19-and-early-childhood-mental-health-fostering-systems-change-and-resilience-policy-brief/

*Mikocka-Walus, A., Stokes, M., Evans, S., Olive, L., & Westrupp, E. (2021). Finding the power within and without: How can we strengthen resilience against symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression in Australian parents during the COVID-19 pandemic?. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 145(0376333, juv), 110433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110433

Mitra, R., Waygood, E. O. D., & Fullan, J. (2021). Subjective well-being of Canadian children and youth during the COVID-19 pandemic: The role of the social and physical environment and healthy movement behaviours. Preventive Medicine Reports, 23(101643766), 101404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101404

Montirosso, R., Mascheroni, E., Guida, E., Piazza, C., Sali, M. E., Molteni, M., & Reni, G. (2021). Stress symptoms and resilience factors in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities and their parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Psychology : Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 40(7), 428–438. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000966

Munoz, R. T., Brady, S., & Brown, V. (2017). The psychology of resilience: A model of the relationship of locus of control to hope among survivors of intimate partner violence. Traumatology, 23(1), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000102

*Nasir, A., Harianto, S., Purwanto, C. R., Indrawait, I. R., Rohman, M., Rahmawati, P. M., & Putra, P. (2021). The outbreak of COVID-19: Resilience and its predictors among parents of schoolchildren carrying out online learning in Indonesia. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100890

Nicolaidou, I., Stavrou, E., & Leonidou, G. (2021). Building primary-school children’s resilience through a web-based interactive learning environment: Quasi-experimental pre-post study. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting, 4(2), e27958. https://doi.org/10.2196/27958

Nikolaidis, A., Paksarian, D., Alexander, L., Derosa, J., Dunn, J., Nielson, D. M., Droney, I., Kang, M., Douka, I., Bromet, E., Milham, M., Stringaris, A., & Merikangas, K. R. (2021). The Coronavirus Health and Impact Survey (CRISIS) reveals reproducible correlates of pandemic-related mood states across the Atlantic. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 8139. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87270-3

O’Keefe, V. M., Maudrie, T. L., Ingalls, A., Kee, C., Masten, K. L., Barlow, A., & Haroz, E. E. (2021). Development and dissemination of a strengths-based indigenous children’s storybook: “Our smallest warriors, our strongest medicine: overcoming covid-19”. Frontiers in Sociology, 6(101777459), 611356. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021.611356

Orgilés, M., Espada, J., Delvecchio, E., Francisco, R., Mazzeschi, C., Pedro, M., & Morales, A. (2021). Anxiety and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic: A transcultural approach. Psicothema, 33(1), 125–130.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2020). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372(71). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Pandya, S. P. (2019). Spiritual education programme for primary caregiver parents to build resilience in children with acute anxiety symptoms: A multicity study. Child & Family Social Work, 24(2), 309–320. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12616

Paré, G., Trudel, M.-C., Jaana, M., & Kitsiou, S. (2015). Synthesizing information systems knowledge: A typology of literature reviews. Information & Management, 22(2), 183–199.

Parrott, J., Armstrong, L. L., Watt, E., Fabes, R., & Timlin, B. (2021). Building resilience during COVID-19: Recommendations for adapting the DREAM Program—live edition to an online-live hybrid model for in-person and virtual classrooms. Frontiers in Psychology, 12(101550902), 647420. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647420

Patton, M. Q. (2005). Qualitative Research. Sage.

Peris, T. S., & Ehrenreich-May, J. (2021). The parents are not alright: A call for caregiver mental health screening during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 60(6), 675–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.02.007

Prime, H., Wade, M., & Browne, D. T. (2020). Risk and resilience in family well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. The American Psychologist, 75(5), 631–643. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000660

*Public Health Agency of Canada [PHAC]. (2020, October). From risk to resilience: An equity approach to COVID-19. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/from-risk-resilience-equity-approach-covid-19.html

Rabbani, M., Haque, M. M., Das Dipal, D., Zarif, M. I. I., Iqbal, A., Schwichtenberg, A., Bansal, N., Soron, T. R., Ahmed, S. I., & Ahamed, S. I. (2021). An mCARE study on patterns of risk and resilience for children with ASD in Bangladesh. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 21342. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00793-7

Reid, H., Miller, W. C., Esfandiari, E., Mohammadi, S., Rash, I., Tao, G., Simpson, E., Leong, K., Matharu, P., Sakakibara, B., Schmidt, J., Jarus, T., Forwell, S., Borisoff, J., Backman, C., Alic, A., Brooks, E., Chan, J., Flockhart, E., & Mortenson, W. B. (2021). The impact of COVID-19-related restrictions on social and daily activities of parents, people with disabilities, and older adults: protocol for a longitudinal. Mixed methods study. JMIR Research Protocols, 10(9), e28337. https://doi.org/10.2196/28337

*Romero, E., Lopez-Romero, L., Dominguez-Alvarez, B., Villar, P., & Gomez-Fraguela, J. A. (2020). Testing the Effects of COVID-19 Confinement in Spanish Children: The Role of Parents’ Distress, Emotional Problems and Specific Parenting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17196975

Roubinov, D., Bush, N. R., & Boyce, W. T. (2020). How a Pandemic Could Advance the Science of Early Adversity. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(12), 1131–1132. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.2354

Ruiz, Y., Wadsworth, S. M. M., Elias, C. M., Marceau, K., Purcell, M. L., Redick, T. S., Richards, E. A., & Schlesinger-Devlin, E. (2020). Ultra-rapid development and deployment of a family resilience program during the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons learned from families tackling tough times together. Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health, 6(2), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.3138/JMVFH-6.S2-CO19-0013

*Russell, B. S., Tomkunas, A. J., Hutchison, M., et al. (2022). The Protective Role of Parent Resilience on Mental Health and the Parent-Child Relationship During COVID-19. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 53, 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-021-01243-1

Schneider, M., Simpson, J., & Zlomke, K. (2021). A comparison study: Caregiver functioning and family resilience among families of children with cystic fibrosis, asthma, and healthy controls. Children’s Health Care, 50(2), 142–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/02739615.2020.1842207

Schrooyen, C., Soenens, B., Waterschoot, J., Vermote, B., Morbee, S., Beyers, W., Brenning, K., Dieleman, L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2021). Parental identity as a resource for parental adaptation during the COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of Family Psychology : JFP : Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 8802265, dlv. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000895

SickKids. (2021, February 26). New research reveals impact of COVID-19 pandemic on child and youth mental health. SickKids. https://www.sickkids.ca/en/news/archive/2021/impact-of-covid-19-pandemic-on-child-youth-mental-health/

Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: assessing the ability to bounce back. International journal of behavioral medicine, 15(3), 194–200. https://doi-org.proxy1.lib.uwo.ca/10.1080/10705500802222972

*Sorkkila, M., & Aunola, K. (2021). Resilience and parental burnout among Finnish parents during the COVID-19 pandemic: Variable and person-oriented approaches. The Family Journal, 1–9.

Steinberg, D. M., Andresen, J. A., Pahl, D. A., Licursi, M., & Rosenthal, S. L. (2021). “I’ve weathered really horrible storms long before this...”: The experiences of parents caring for children with hematological and oncological conditions during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 9435680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-020-09760-2

Suarez-Lopez, J. R., Cairns, M. R., Sripada, K., Quiros-Alcala, L., Mielke, H. W., Eskenazi, B., Etzel, R. A., & Kordas, K. (2021). COVID-19 and children’s health in the United States: Consideration of physical and social environments during the pandemic. Environmental Resilience. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111160

Tang, S., Xiang, M., Cheung, T., & Xiang, Y. (2021). Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: The importance of parent-child discussion. Journal of Affective Disorders, 279, 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.016

Tokatly Latzer, I., Leitner, Y., & Karnieli-Miller, O. (2021). Core experiences of parents of children with autism during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Autism : The International Journal of Research and Practice, 25(4), 1047–1059. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320984317

Torres Fernandez, I., Schwartz, J. P., Chun, H., & Dickson, G. (2013). Family resilience and parenting. In D. S. Becvar (Ed.), Handbook of family resilience (pp. 119–136). Springer.

*Touloupis, T. (2021). Parental involvement in homework of children with learning disabilities during distance learning: Relations with fear of COVID-19 and resilience. Psychology in the Schools, 58(12), 2345–2360. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22596

UNESCO. (2021). Primary school starting age (years). The World Bank: UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved September 1, 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.PRM.AGES?end=2020&start=2020&view=map

Ungar, M., & Liebenberg, L. (2011). Assessing Resilience Across Cultures Using Mixed Methods: Construction of the Child and Youth Resilience Measure. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 5(2), 126–149.

United Nations. (2020). Policy brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond. Retrieved September 21, 2021. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/08/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_august_2020.pdf

van Tilburg, M. A. L., Edlynn, E., Maddaloni, M., van Kempen, K., Diaz-Gonzalez de Ferris, M., & Thomas, J. (2020). High levels of stress due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic among parents of children with and without chronic conditions across the USA. Children (Basel, Switzerland), 7(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/children7100193

Vanier Institute of the Family. (2020). Families struggle to cope with financial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. https://vanierinstitute.ca/families-struggle-to-cope-with-financialimpacts-of-the-covid-19-pandemic/

Vertsberger, D., Roskam, I., Talmon, A., van Bakel, H., Hall, R., Mikolajczak, M., & Gross, J. J. (2022). Emotion regulation during the COVID-19 pandemic: Risk and resilience factors for parental burnout (IIPB). Cognition and Emotion, 36(1), 100–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2021.2005544

Wagnild, G. (2009). A review of the resilience scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 17(2), 105–113.https://doi-org.proxy1.lib.uwo.ca/10.1891/1061-3749.17.2.105

Wang, X., & Cheng, Z. (2020). Cross-Sectional Studies: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Recommendations. Chest, 158(1), 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.012

White, S. W., Stoppelbein, L., Scott, H., & Spain, D. (2021). It took a pandemic: Perspectives on impact, stress, and telehealth from caregivers of people with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 113(8709782, rid), 103938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2021.103938

Williams, K. (2020). Navigating the COVID-19 pandemic: The future of children and young people. Child & Youth Services, 41(3), 320–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2020.1835211

World Health Organization. (2020, April 27). Archived: WHO Timeline – COVID-19. https://www.who.int/news/item/27-04-2020-who-timeline---covid-19

Wu, Q., Xu, Y., & Jedwab, M. (2021). Custodial grandparent’s job loss during the COVID-19 pandemic and its relationship with parenting stress and mental health. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 40(9), 923–933. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648211006222

Xie, X., Xue, Q., Zhou, Y., Zhu, K., Liu, Q., Zhang, J., & Song, R. (2020). Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei province, China. JAMA Pediatrics, 174(9), 898–900.

Yeasmin, S., Banik, R., Hossain, S., Hossain, M., Mahumud, R., Salma, N., & Hossain, M. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of children in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. Children and Youth Services Review, 117, 105277.

Zilberstein, K. (2021). Debate: Coping and resilience in the time of COVID-19 and structural inequities. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 26(3), 279–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12484

Zhou, S., Zhang, L., Wang, L., Guo, Z., Wang, J., Chen, J., et al. (2020). Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(6), 749–758.

Zolkoski, S. M., & Bullock, L. M. (2012). Resilience in children and youth: A review. Children and Youth Services Review, 34, 2295–2303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.08.009

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

Database Search Strategy

Concept | Search Terms |

|---|---|

1. Caregivers | 1. (caregiver* or care giver* or parent* or caretaker* or guardian*).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] |

2. Children | 2. (child* or kid*).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] |

3. Resilience | 3. exp Resilience, Psychological/ or Resilien*.mp |

4. COVID-19 | 4. COVID-19/ or exp COVID-19 Testing/ or COVID-19 Vaccines/ or SARS-CoV-2/ 5. (coronavirus/ or betacoronavirus/ or coronavirus infections/) and (disease outbreaks/ or epidemics/ or pandemics/) 6. (nCoV* or 2019nCoV or 19nCoV or COVID19* or COVID or SARS-COV-2 or SARSCOV-2 or SARS-COV2 or SARSCOV2 or SARS coronavirus 2 or Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 or Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Corona Virus 2).ti,ab,kf,nm,ot,ox,rx,px 7. (longCOVID* or postCOVID* or postcoronavirus* or postSARS*).ti,ab,kf,ot 8. ((coronavirus* or corona virus* or betacoronavirus*) adj3 (pandemic* or epidemic* or outbreak* or crisis)).ti,ab,kf,ot 9. ((Wuhan or Hubei) adj5 pneumonia).ti,ab,kf,ot 10. or/4–9 |

11. 1 and 2 and 3 and 10 |

Appendix B

List of Excluded Studies and Reasons for Exclusion

Reason for Exclusion | Authors of Excluded Studies |

|---|---|

Resilience in caregivers and/or children not discussed in results | Ajanovic et al., 2021; Ashikkali et al., 2020; Brunelli et al., 2021; Cauberghe et al., 2021; Crescentini et al., 2020; Daks et al., 2020; Erdei & Liu, 2020; Fegert et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2021; Kamran & Naeim, 2021; Levine, 2020; Mactavish et al., 2021; Marchetti et al., 2020; Matiz et al., 2022; Nicolaidou et al., 2021; O’Keefe et al., 2021; Parrott et al., 2021; Peris & Ehrenreich-May, 2021; Rabbani et al., 2021; Roubinov et al., 2020; Schrooyen et al., 2021; Steinberg et al., 2021; A L van Tilburg et al., 2020; Vertsberger et al., 2022; White et al., 2021; Williams, 2020; Wu et al., 2021 |

Study not conducted in the COVID-19 context | Kim et al., 2020; Pandya, 2019; Schneider et al., 2021 |

Mean age of children outside of 7–10 range | Andres-Romero et al., 2021; Archer et al., 2021; Asscheman et al., 2021; Bates et al., 2021; Biden et al., 2021; Bryson et al., 2021; Davidson et al., 2021; Eales et al., 2021; Feng et al., 2020; Gibbons et al., 2021; Hatzichristou et al., 2021; Herbert et al., 2020; Hong et al., 2021; Iovino et al., 2021; Jungmann et al., 2021; Kohler-Dauner et al., 2021; Lawrence et al., 2021; Luthar et al., 2020; Mitra et al., 2021; Montirosso et al., 2021; Nikolaidis et al., 2021; Ruiz et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2021; Thibodeau-Nielsen et al., 2021; Tokatly Latzer et al., 2021; Tso et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021; Wimberly et al., 2021; Wong et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2022; |

Article is not primary research or grey literature | Berger et al., 2021; Lateef et al., 2021; Prime et al., 2020; Reid et al., 2021; Zilberstein et al., 2021 |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Yates, J., Mantler, T. The Resilience of Caregivers and Children in the Context of COVID-19: A Systematic Review. Journ Child Adol Trauma 16, 819–838 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-022-00514-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-022-00514-w