Abstract

Introduction and Background

Racial minorities have been the focal point of media coverage, attributing the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 to their individual actions; however, the ability to engage in preventative practices can also depend on one’s social determinants of health. Individual actions can include knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAPs). Since Black communities are among those disproportionately affected by COVID-19, this scoping review explores what is known about COVID-19 KAPs among Black populations.

Methods

A comprehensive literature search was conducted in 2020 for articles written in English from the Medline, Embase, and PsycInfo databases. Reviews, experimental research, and observational studies were included if they investigated at least one of COVID-19 KAP in relation to the pandemic and Black communities in OECD peer countries including Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom.

Results and Analysis

Thirty-one articles were included for analysis, and all employed observational designs were from the United States. The following KAPs were examined: 6 (18.8%) knowledge, 21 (65.6%) attitudes, and 22 (68.8%) practices. Black communities demonstrated high levels of adherence to preventative measures (e.g., lockdowns) and practices (e.g., mask wearing), despite a strong proportion of participants believing they were less likely to become infected with the virus, and having lower levels of COVID-19 knowledge, than other racial groups.

Conclusions and Implications

The findings from this review support that Black communities highly engage in COVID-19 preventative practices within their realm of control such as mask-wearing and hand washing and suggest that low knowledge does not predict low practice scores among this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic was declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March of 2020 [1]. Vaccines for COVID-19 have been widely distributed globally since December 2020. Prior to the introduction of the vaccine, behavioral change such as social distancing—a public health measure of maintaining physical distance from others—was the most effective means of reducing disease transmission [2].

Behavioral preventative measures promoted by public health authorities include wearing masks, hand washing, social distancing, disinfecting frequently touched shared surfaces, and the self-isolation of those who are symptomatic or have been exposed to the virus [2]. Some of these preventative measures are easier to follow for some and structurally very difficult for others, particularly those from marginalized communities [3]. For example, self-isolation is extremely challenging in households with multiple families or in settings such as jails and prisons [3]. Face mask mandates have been problematic for many Black men due to anti-Black stereotypes associated with a threatening demeanor when using face coverings [3]. In addition, the ability to social distance is linked to structural factors such as housing and socioeconomic status [4].

During the height of the pandemic, services necessary for the safety, sanitation, and necessary operations of society were deemed “essential” and continued to require workers to attend in-person even during lockdowns when everyone was encouraged to stay and work at home. Many lower-wage jobs have been deemed “essential” and involve high contact with the public (e.g., cashiers, sanitation workers, home health aides, food service workers), thereby limiting one’s ability to social distance and increased risk of exposure to the virus [5]. Data from 2018 by the Urban Institute representing 152.7 million workers found that thirty-three percent of Black workers were in essential jobs that required them to work in person and in close proximity to others, while just twenty-six percent of White workers had similar jobs [6]. As such, the ability to practice social distancing is related to the context in which one lives and works rather than exclusively a practice that relies on personal discipline [4].

Many disparities that emerged from the pandemic have been the result of a legacy of structural inequity which disproportionately impacts historically marginalized populations [3]. In high-income peer countries such as the United States (U.S), the United Kingdom (U.K), Australia, the Netherlands, and Canada, COVID-19 cases were found to be disproportionately concentrated in areas with lower socioeconomic status and areas with higher populations of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities, new immigrants, and essential workers [7,8,9,10,11].

One’s individual actions are commonly cited as detrimental, particularly in the context of a pandemic [12]. Historically marginalized, racialized communities have been the focal point of media coverage, attributing their individual actions as a cause of rising COVID-19 numbers [13,14,15,16,17,18]. In the media, the disproportionate illness and exposure to COVID-19 among BIPOC people was originally framed as deficit discourse and did not adequately describe the systemic factors that have led to COVID-19 disparities [13]. When asked to comment about the disparity between the rate at which Black Americans contract COVID-19 in comparison to other racial groups, U.S Surgeon General Jerome Adams was criticized when he said, “African-Americans and Latinos should avoid alcohol, drugs and tobacco” [14]. Texan Lieutenant Governor, Dan Patrick, also attributed blame to Black residents for the state’s summer 2021 COVID-19 waves [15]. In April 2020, Nova Scotian Premier Stephen McNiel criticized the social behaviors of those in North and East Preston, predominantly Black communities, for the provincial uptick in COVID-19 cases [19].

Despite the emphasis on individual action, health equity scholars have attributed these racial disparities in COVID-19 blame, as well as disproportional pandemic morbidity, to structural racism. Health equity scholars, Bailey and colleagues [20], define structural racism as “the totality of ways in which societies foster racial discrimination through mutually reinforcing systems” which “reinforce[s] discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources.” The impacts of structural racism can be revealed when sociodemographic data is collected [21]. Race-based information on COVID-19 patients is not being collected on a national scale across Canada and Australia (Chin Tan, 2020). Ethnic and race-based data from peer countries such as the U.S, the Netherlands, the U.K, and Canada reveal that Black communities have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic [7, 8, 10, 22, 23].

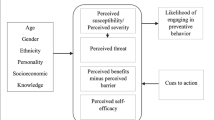

In light of public attention to the individual actions of marginalized communities for their disproportionate COVID-19 impact, the empirical knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAPs) of Black communities were explored in this review. KAPs have been cited as a factor in adherence to pandemic control measures [24]. The knowledge of a community elucidates their level of understanding on a topic, their attitudes provide clarity on how they feel about the information they know, and their practice can indicate how the community’s knowledge and attitudes manifest in their actions [25]. Nonetheless, substandard levels of KAPs are known to be influenced by underlying socio-ecological factors such as poverty and sociocultural issues [23, 24]. A KAPs approach is widely used in health research and is used to gather more information about the health-seeking practices of a population [26]. An assessment of KAPs can play a key role in understanding and adopting public health approaches for controlling the spread of COVID-19 and future outbreaks to come.

Scoping reviews exist on the KAPs of Black populations with respect to health workers’ assessment, surveillance, and management of COVID-19 and HIV/AIDS [27, 28]. To the authors’ knowledge, no scoping review has been published with respect to the COVID-19 knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Black populations. The intersection of a deficit discourse, medical mistrust, and marginalization of Black communities during the COVID-19 pandemic has situated this population as of great interest to scholars and public health experts [29, 30]. As such, the aim of this review was to explore and summarize what is known about the KAPs of Black communities with respect to COVID-19. In this review, the term “Black people” is used throughout to denote communities of African ancestry and acknowledge the diversity of the African diaspora.

Methods

This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR)[31]. A scoping review methodology was selected to examine and summarize the range of literature available on the COVID-19 KAPs of Black communities.

Search Strategy

The databases Medline, PsycInfo, and Embase were searched to identify relevant articles. The search strategy involved using keywords, index terms, and Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms in Medline and PsycInfo and Emtree terms in Embase for concepts encapsulating the population of interest (Black communities), the COVID-19 pandemic, outcomes (KAPs), and residence in OECD peer countries. The key search terms included black communit*, health knowledge, health behavior, coronavirus*, and health attitude*. A detailed description of the search strategy can be found in Appendix 1.

Article Selection and Eligibility

For an article to qualify for inclusion, it had to meet the following criteria: (1) measure at least one or more of the COVID-19 KAP characteristics; (2) examine Black populations in Canada’s OECD peer countries Australia, France, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden, the U.S, Australia, and/or the U.K [32]; (3) English language; (4) peer reviewed; and (5) published in 2020. The year 2020 was selected because the WHO declared COVID-19 a global pandemic in March 2020, and thus, the global community’s knowledge, attitudes, and practices of COVID-19 were novel during this time [1]. Reviews, experimental research, and observational studies employing diverse methodological approaches (e.g., quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods) were considered for inclusion to capture the broad scope of literature. Articles were excluded if they combined data with unidentified countries and if they reported KAP outcomes for Black populations in conjunction with other racial groups in an indistinguishable manner.

The articles were imported into Covidence for a two-stage screening process [33]. The first stage consisted of title and abstract review which led to full-text review. Two independent reviewers (FW and FB) conducted screening of the selected articles using the inclusion criteria to identify relevant publications, and any conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer (JP).

Data Charting Process

The reviewers independently reviewed the selected articles and developed a data charting form on Covidence to document article details (journal, publication month, names of authors, country of origin), study characteristics (methodology, sample size, setting, aim), participant demographics (gender, age), and key findings (knowledge, attitudes, or practices). Two reviewers refined the data chart in an iterative process of extracting the data, analyzing the full texts, and charting pertinent information until all articles were extracted in the final data chart, exported to Microsoft Excel. Appendix 2 displays the charted data.

Synthesis of Results

Numeric analysis was used to summarize study characteristics, participant demographic characteristics, and outcomes. A modified narrative synthesis approach was used to summarize results since the articles varied in terms of research designs and data outcomes [34, 35]. The stages of the narrative synthesis included the following: (1) developing the preliminary synthesis, (2) comparing themes within and between studies, and (3) thematic classification [34, 35]. In (1) developing the preliminary synthesis, a deductive approach was used to thematically categorize articles into each KAP characteristic. An inductive approach was used to develop subthemes by (2) comparing themes within and between studies. Three authors (FW, FB, and JP) reviewed the thematic classifications of emerging themes and subthemes.

Results

The literature search retrieved 1582 articles, and 259 were duplicates. Fifteen thousand and one were excluded following title and abstract scan (Fig. 1.). Sixty-five articles underwent full-text review, and a total of 31 studies were included in this review.

Numeric Analysis

All eligible articles were published in the U.S. Six (19.4%) of 31 studies examined knowledge, twenty-one (67.7%) examined attitudes, and twenty-two studies (71.0%) examined practices. Two of the 31 (6.5%) studies examined all three KAPs.

Study Characteristics

All included articles employed observational designs, with the majority of studies employing cross-sectional surveys (N = 24, 77.4%). The design of the remaining observational studies included 1 case study, 3 qualitative studies, and 3 cohort studies. Eighteen of the cross-sectional surveys were self-administered. The other 6 were administered via phone or teleconferencing app or derived from unspecified secondary data.

Sixteen of the 24 cross-sectional studies employed a tertiary survey service to obtain a national or state-wide representative sample (n = 16, 72.73%). Other recruitment methods included surveying patients hospitalized in a medical center via social media platforms and community agencies. Among the cross-sectional studies, sample sizes ranged from 101 to 10,510 participants, and the five cross-sectional studies that reported completion rates varied from 14.4 to 93%. Twenty studies (64.5%) utilized web-based methods of data collection such as email, SMS, or video teleconferencing. Though studies typically define race through self-identification [36], 17 (51.5%) of the included studies did not specify how racial categories were assigned (e.g., self-identification). See Appendix 1 for a summary of included article characteristics.

Participant Characteristics

Participants of the cross-sectional studies were all U.S residents. Eleven (45.8%) of the cross-sectional studies recruited a representative sample across the U.S, one of which oversampled in COVID-19 hotspots at the time [37]. Participants from 4 of the 24 cross-sectional studies were recruited based on state or municipal residence and included studies based in Chicago, Maryland, New York City, and 1 study recruiting residents in 6 unnamed states [5, 33,34,35,36, 35]. Two cross-sectional studies recruited parents and guardians with at least one school-aged child [37, 38]. Five studies (including all 4 qualitative studies) recruited Black adults exclusively, 1 of which was specific to HIV-positive Black people and 1 was focused on Black women.

Synthesis of Results

Knowledge Related to COVID-19

Studies assessed knowledge in 7 of the 31 studies. Knowledge levels were relatively low among Black populations in comparison to their White counterparts [37, 38, 40,41,42,43,44]. This includes Black populations being less likely to identify COVID-19 symptoms [37, 38, 44], correctly estimate numbers of cases and deaths [40], correctly report that there was not a vaccine for COVID-19 at the time of the survey [41], and correctly report COVID-19 transmission routes as via respiratory droplets or fomite transmission [37, 41]. With respect to knowledge of COVID-19 disparities, Black respondents had significantly lower odds than White participants of agreeing that there were disparities in COVID-19 mortality by age and by chronic health conditions [42]. In contrast, a cross-sectional study by Alobuia and colleagues [43] found that Black participants had a lower median knowledge score than White participants but the same score as Hispanic, Asian, and mixed participants.

Attitudes Related to COVID-19

Twenty of the 31 studies assessed attitudes related to COVID-19. Attitudes were defined as the beliefs or feelings Black participants harbored toward COVID-19-related events or policies. Four subthemes were identified: (1) perceived susceptibility, (2) mistrust and racism, (3) government response, and (4) vaccines.

Perceived Susceptibility

In 2 studies, Black participants were more likely to believe that they were unlikely to become infected with COVID-19 [38, 42]. In a study by Gollust and colleagues [42], the level of agreement to the phrase “Blacks/African Americans are more likely to die of complications of COVID-19 than White people” was higher among White (OR = 1.00) and Hispanic (OR = 1.29) participants than Black (OR = 0.94) and other/multiracial (OR = 0.69) participants. Bailey and colleagues [38] found that 30% of Black respondents reported they were “not at all likely to get sick [from COVID-19]” when compared to 17.4% of White respondents. Furthermore, adults who were Black, living under the poverty baseline, and had low health literacy believed that it was unlikely that they would become sick [38]. Conversely, in another cross-sectional study of American adults, non-Hispanic Black (34.4%) participants had a higher perceived likelihood of currently having COVID-19 compared to Asian (21.6%) and non-Hispanic White (20.9%) participants [40].

Mistrust and Racism

Four studies indicated some level of confusion and mistrust with COVID-19 information among Black participants [45,46,47,48]. Chen-Sankey and colleagues [45] found that a few participants mentioned their mistrust of health authorities or COVID-19 messaging disseminated by health experts since official statements were often contradictory. In a qualitative study of HIV-positive Black Americans, 97% endorsed at least one general COVID-19 mistrust belief, such as the government withholding COVID-19 information from the general public [46]. Similarly, a qualitative study of Black women found that 79% indicated confusion with the COVID-19 information that they received from varied sources, including the news and social media [47].

Moreover, Black participants cited structural racism and discrimination as a causal factor to the disproportionate negative impact of COVID-19 among the Black population [48,49,50]. Black participants reported stories of discriminatory experiences with the medical system inducing medical racism [48, 49]. For example, the Black respondents described feeling neglected and expendable by healthcare providers, especially as low-income individuals seeking COVID-19 testing and care [48]. In focus groups of Black Americans by Ordaz-Johnson and colleagues [49], participants shared their beliefs of the source of disproportionate COVID-19 risk—outside of underlying health conditions. Implicit bias within healthcare was noted as a believed source of disproportionate COVID-19 risk among Black Americans.

Government Response

Two studies demonstrated that Black participants were more supportive than non-Black counterparts to government responses to the pandemic [51, 52]. Black participants were in greater support of risk mitigation measures such as lockdowns and school closures than White participants [51] and compared to White and Hispanic parents [52]. For example, compared to White parents of which 62.3% strongly or somewhat agreed that schools should reopen in-person for all students in fall 2020, a smaller percentage of Black parents (46.0%) agreed [52].

Vaccine

Black Americans were reported as demonstrating lower vaccine acceptance across 4 studies [46, 53,54,55]. In the cross-sectional study of Guidry and colleagues [53], intent to get a future COVID-19 vaccine was lower in Black participants than all other racial groups. Lower educational attainment, Black race, not having had a recent influenza vaccination, and lower perceived personal risk for COVID-19 were independent predictors of being hesitant toward receiving the COVID-19 vaccine [54].

Practices Related to COVID-19

Practices were assessed in 21 of the 31 studies, and 3 subthemes were identified: (1) employment-related practices, (2) public health practices, and (3) access to health services and information.

Employment-Related Practices

Seven studies reported that Black participants were less likely to be able to work from home and social distance despite public health measures encouraging Americans to do so to mitigate spread of COVID-19 [5, 37, 44, 48, 50, 56, 57]. In a cross-sectional study of Chicago residents, Black participants were less likely than Latinx participants to report feeling unsafe commuting to work during the pandemic and were less likely than White participants to report having no household members with compromised immune systems [56]. In the context of the preventative measure to stay home during the pandemic, Alsan and colleagues [37] reported that Black Americans left the home more than all racial groups and left the home approximately 2.9 times within the last 3 days of completing the survey.

Public Health-Related Practices

Six studies highlighted that Black participants were more likely to more frequently practice COVID-19 hygiene behaviors than other racial groups [37, 43, 54, 50, 57,58,59]. The highest rates of face mask covering use were observed in and sustained most by Black participants in comparison to comparator racial groups [54, 58]. Black respondents reported greater endorsement of preventative practices (e.g., wearing a mask, hand washing) than inadequate practices (e.g., traveling, attending large gatherings) [43]. In the same study, endorsement of these preventative practices was not associated with high knowledge scores among respondents.

Furthermore, Black participants reported more frequent effort in cleaning frequently touched surfaces than White participants during the early phase of wave 1 when this was a promoted technique thought to reduce potential exposures [50]. Although Black participants had greater rates of preventative health practices compared to all other racial groups, 3 studies found that Black participants were less likely to report practicing social distancing [44, 48, 56].

Access to Health Services and Information

In terms of healthcare access, Black patients had 0.6 times the adjusted odds of accessing care through telemedicine compared to White patients [60]. However, the adjusted odds increased between 2019 and 2020 due to a larger proportion of virtual urgent care visits by a Black population that was younger and included a greater number of female participants [60]. Chunara and colleagues [60] also found that Black participants were more likely to use the emergency department and office visits than telemedicine.

Chandler and colleagues [47] reported that 67% of Black women got COVID-19 information from a combination of social media, television, the Internet, and social networks. Fifty-eight percent used apps like Facebook and Instagram to access information, and 33% used email updates, texts, group messaging, subscriptions to health sites, and information from family and friends [47].

Discussion

This scoping review summarizes the literature published on the KAPs of Black populations with respect to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. According to the World Health Organization, KAP surveys can identify knowledge gaps, cultural beliefs, or behavioral patterns that may facilitate understanding and action, as well as pose problems or create barriers for disease control efforts and can contribute fundamental information needed to make strategic decisions [61].

Of the studies that examined knowledge, low knowledge scores were frequently reported among the Black participants compared to other racial groups [37, 38, 40,41,42,43,44]. Inadequate levels of KAP, particularly knowledge scores, are known to be influenced by underlying social determinants of health such as poverty [39, 62]. For example, economic barriers that manifest as the inability to access timely healthcare and internet access can impede individuals from accessing the health information the need to prevent COVID-19 infection [39]. In addition, these economic barriers can affect access to telemedicine care among Black communities. Chunara and colleagues [60] found a lower likelihood among Black participants to engage in telemedicine during the pandemic in comparison to White populations. These findings echo well-documented challenges in healthcare for Black patients due to an array of factors such as lack of resource access, as well as bias and cultural competencies among providers [60].

An interesting finding in this review contrasts the hypothesis put forward by Alobuia and colleagues [43] that knowledge is correlated to practice, meaning that high knowledge scores would generate high practice scores and vice versa. This scoping review suggests that knowledge does not reliably predict practices. The hypothesis assumes that individuals have control over the behaviors they can practice, but as this review highlights, this is not always the case. Black people in the U.S are more likely to be employed in essential work fields and use public transit [5, 63, 64], than their non-Black counterparts. Therefore, low rates of social distancing practice may be more closely associated with employment in an essential field of work than knowledge [5, 37, 44, 48, 50, 56, 57]. Despite the various structural barriers to adopt preventative measures, including inadequate housing and essential work [3], among the behaviors within their locus of control (e.g., mask wearing and cleaning frequently touched surfaces), Black populations reported uptake of more COVID-19 preventative practices than other racial groups.

Four studies note COVID-19 information-based concerns such as the circulation of misinformation and confusion from news sources consumed [50,51,52,53, 55]. As federal governments provided inadequate and inconsistent messaging particularly at the start of the pandemic, uncertainty mounted among the public [65]. Experiences from past infectious disease outbreaks (e.g., H1N1, Ebola virus, HIV) have been accompanied with misinformation and stigma, particularly among marginalized populations, which have hindered the containment of disease and prevention measures in the past [66]. Misinformation can resonate strongly with those experiencing ongoing stigmatization and exclusion in healthcare, government, law enforcement, and criminal justice systems [65].

Medical mistrust was a common thread in studies discussing respondents’ attitudes and has been well-documented among Black communities [30, 46, 53,54,55]. Medical mistrust and vaccine hesitancy were consistently high within the Black population [46, 53,54,55]. Bailey and colleagues [38] shared data that Black participants perceived a low susceptibility to contracting the COVID-19 virus. Perceived susceptibility can shape vaccine acceptance as studies have shown that those with high perceived susceptibility to COVID-19 infection were associated with a higher likelihood of accepting COVID-19 vaccinations [67]. Among the 3 studies that assessed COVID-19 vaccine intent across all racial groups, all indicated a higher tendency for vaccine hesitancy in Black participants than all other racial groups [53,54,55]. This finding may be connected to the history of medical racism experienced by Black Americans. Throughout history, Black people in Western nations have been seen and treated as genetically different, inferior, and more pain-tolerant than White people [68]. This has origins in the abuse of Black people during slavery and continues to impact contemporary healthcare [68]. In a 2016 study by Hoffman and colleagues, half of the sampled medical trainees endorsed at least one myth about the differences between Black and White patients. These include such myths as Black people have thicker skin or less sensitive nerve endings than White people [69]. The biases held by medical professionals can have fatal consequences when combined with the legacy of medical racism and intersecting systems of oppression (such as poverty); all of which likely influence the apprehensive zeitgeist to COVID-19 susceptibility and vaccination among Black communities.

Despite findings reporting low levels of vaccine acceptance, in this review, Black populations were in greater support for stronger public health risk mitigation efforts such as lockdowns and keeping schools closed. Data from the Toronto District School Board found that Black elementary students experienced the greatest reading improvement during the pandemic between January 2019 and January 2021 as compared to their White and East Asian peers [70].

While socioeconomic and racial disparities have been observed to contribute significantly to students’ access to technology [71], experts have commented that the online nature of education may have created a learning environment free of racism—from both educators and peers—typically experienced at school [71].

The discrepancies between the high preventative practices and high rates of infection among Black communities have not only been observed for COVID-19. In a literature review examining HIV-related sexual health practices for Black men who have sex with men (MSM), researchers found similar discrepancies between practices and disease incidence. HIV prevalence and incidence rates are significantly higher for Black MSM, and unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) is the single most important risk factor for HIV transmission among MSM; however, most studies published from the first decade of the HIV/AIDS epidemic through the present have found comparable, if not lower, self-reported rates of UAI for Black MSM relative to other MSM [63]. The findings from this scoping review support the broader literature outlining these discrepancies between the practices of marginalized, Black communities, and the diseases that disproportionately harm them.

Implications

The findings of this scoping review shed light on the discrepancy between adherence to COVID-19 preventative practices among Black people versus their disproportionate illness and death from COVID-19. Similarly, early KAPs research of HIV/AIDs found similar discrepancies between practices and rates of illness and death [63]. There is a need to explore this phenomenon further.

These findings are especially significant in light of recent calls to collect and standardize race-based data to identify pandemic inequities that disproportionately affect certain groups. When examining race-based data, what is being assessed is the impact of racialization, that is, the process of ascribing a race to a group and the subjection to unequal treatment as a result [21]. There are several risks when engaging in race-based data such as its use to create deficit discourse and misinterpret racial differences as biological differences [21]. Nonetheless, the benefits need to be weighed against the risks. Race-based health data is currently not available at the provincial or state level in OECD countries such as Canada and Australia, and where data is available, the way it is collected often varies. Without data of this nature, systemic changes that address inequality and discriminatory policies are difficult to accomplish [72]. The emerging need for disaggregated race-based data needs to be paired with procedures to ensure high-quality and risk-averse data.

COVID-19 messaging has focused more on the individual risks than the community risks that have resulted from pre-existing inequities [73]. The findings of this scoping review support efforts to also communicate environmental and situational risk. The conventional epidemiologic focus on risk factors places the burden of behavior change on individuals rather than the contexts that largely define their vulnerability [73].

This scoping review summarizes what is known about COVID-19 KAPs among U.S Black populations. This review supports the wealth of literature demonstrating that efforts to promote preventative practices (to reduce disease incidence) are inadequate when combatting structural barriers in a marginalized population. Despite the efforts of marginalized communities, much of their exposure to COVID-19 is beyond their locus of control. COVID-19 mitigation efforts that focus on individual behavior such as handwashing and physical distancing must be met with structural mitigation efforts such as paid sick days and access to quality housing to ensure the safety and protection of marginalized communities.

Limitations

The results of this scoping review followed the PRISMA guideline; however, there is still a possibility that relevant articles were omitted, especially since the search was limited to studies published in English. Due to variation in categories used to classify racial and ethnic data, comparisons between included studies may be limited to the definition of Black identity by each study. Since all included studies employed an observational design, predominately cross-sectional, there is a possibility of response bias in the self-reported data. In addition, since the pandemic and response to it has changed over time, so may these results.

Conclusion

Overall, despite low COVID-19 knowledge and high levels of medical mistrust attitudes among Black respondents, this review shows that this population is highly engaged in COVID-19 preventative practices. The findings of this review shed light on the discrepancy between the Black participants’ high adherence to COVID-19 preventative practices versus their disproportionate illness and death from COVID-19. KAPs do not exist in a vacuum and are still heavily influenced by socio-ecological factors that are outside of one’s realm of control. Although the knowledge, beliefs, and behaviors of an individual are ostensibly an individualized trait, analyses of KAPs can also shed light on the various ways structural factors can influence such seemingly personal variables.

Appendix 1 Search strategies

Medline Search Strategy

-

1. *knowledge/

-

2. health knowledge.mp.

-

3. health beliefs.mp.

-

4. exp "Surveys and Questionnaires"/

-

5. attitude to health/ or health knowledge, attitudes, practice/

-

6. exp Health Literacy/

-

7. African Americans.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms].

-

8. Black American.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms].

-

9. Black Canadians.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms].

-

10. urban health.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms].

-

11. minority health.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms].

-

12. black people.mp.

-

13. racism.mp.

-

14. racial.mp.

-

15. ethnic*.mp.

-

16. Black communit*.mp.

-

17. Black populat*.mp.

-

18. race*.mp.

-

19. exp Health Promotion/

-

20. exp preventive health services/ or exp health education/

-

21. exp attitude to health/ or exp health knowledge, attitudes, practice/

-

22. misinform*.mp.

-

23. medical mistrust.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms].

-

24. exp Health Communication/

-

25. exp health behavior/ or exp information seeking behavior/

-

26. exp Fear/

-

27. exp information dissemination/ or exp information literacy/ or exp health literacy/

-

28. exp Public Health/

-

29. disease outbreaks/ or epidemics/ or pandemics/ or (coronavirus* or 2019-ncov or ncov19 or ncov-19 or 2019-novel Cov or ncov or covid or covid19 or covid-19 or covid 2019 or "coronavirus 2" or sars-cov2 or sars-cov-2 or sarscov2 or sarscov-2 or sars-coronavirus2 or sars-coronavirus-2 or SARS-like coronavirus* or coronavirus-19 or corona virus* or novel coronavirus*).mp.

-

30. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28.

-

31. 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18.

-

32. 29 and 30 and 31

Psych Info Search Strategy

-

1. exp Health Knowledge/

-

2. exp Health Behavior/

-

3. risk perception/

-

4. exp Public Health/

-

5. exp Attitudes/

-

6. exp Health Belief Model/

-

7. exp Health Attitudes/

-

8. (health knowledge, attitudes and practice).mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh].

-

9. exp Health Literacy/

-

10. exp Health Education/

-

11. exp Preventive Health Services/

-

12. exp Health Promotion/

-

13. exp Health Information/

-

14. exp Mass Media/

-

15. exp Communication/

-

16. exp Health Care Seeking Behavior/ or exp Information Seeking/

-

17. exp Information Dissemination/

-

18. misinform*.mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh].

-

19. exp Blacks/

-

20. exp Racism/

-

21. exp "Racial and Ethnic Differences"/

-

22. exp Ethnic Identity/

-

23. exp "Racial and Ethnic Attitudes"/

-

24. African american*.mp.

-

25. exp Sociocultural Factors/

-

26. exp Poverty Areas/ or exp Urban Health/ or exp Social Class/ or exp Social Deprivation/

-

27. ethnic*.mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh].

-

28. disease outbreaks/ or epidemics/ or pandemics/ or (coronavirus* or 2019-ncov or ncov19 or ncov-19 or 2019-novel Cov or ncov or covid or covid19 or covid-19 or covid 2019 or "coronavirus 2" or sars-cov2 or sars-cov-2 or sarscov2 or sarscov-2 or sars-coronavirus2 or sars-coronavirus-2 or SARS-like coronavirus* or coronavirus-19 or corona virus* or novel coronavirus*).mp.

-

29. exp Treatment Barriers/

-

30. exp Sociocultural Factors/

-

31. exp fear/

-

32. exp Health Disparities/

-

33. medical mistrust.mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh].

-

34. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 29 or 31 or 33.

-

35. 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 30 or 32.

-

36. 28 and 34 and 35.

Embase Search Strategy

-

1. exp attitude to health/

-

2. exp attitude to illness/

-

3. exp health behavior/

-

4. exp behavior/

-

5. exp health belief/

-

6. (health knowledge, attitudes and practices).mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword, floating subheading word, candidate term word].

-

7. exp health literacy/

-

8. exp health education/

-

9. exp fear/

-

10. medical mistrust.mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword, floating subheading word, candidate term word].

-

11. exp preventive health service/

-

12. exp health promotion/

-

13. exp medical information/

-

14. exp mass communication/

-

15. exp public health/

-

16. exp information dissemination/

-

17. misinform*.mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword, floating subheading word, candidate term word].

-

18. exp black person/

-

19. exp race relation/

-

20. exp racism/

-

21. exp cultural factor/

-

22. exp urban health/

-

23. exp urban population/

-

24. exp social class/

-

25. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17

-

26. exp race/

-

27. exp race difference/

-

28. exp African American/

-

29. 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 26 or 27 or 28

-

30. disease outbreaks/ or epidemics/ or pandemics/ or (coronavirus* or 2019-ncov or ncov19 or ncov-19 or 2019-novel Cov or ncov or covid or covid19 or covid-19 or covid 2019 or "coronavirus 2" or sars-cov2 or sars-cov-2 or sarscov2 or sarscov-2 or sars-coronavirus2 or sars-coronavirus-2 or SARS-like coronavirus* or coronavirus-19 or corona virus* or novel coronavirus*).mp. [mp = title, abstract, heading word, drug trade name, original title, device manufacturer, drug manufacturer, device trade name, keyword, floating subheading word, candidate term word].

-

31. 25 and 29 and 30

Appendix 2

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

References

WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. Geneva, Switzerland, Mar. 11, 2020. Available: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. Accessed Jul 20 2022.

Shook NJ, Sevi B, Lee J, Oosterhoff B, Fitzgerald HN. Disease avoidance in the time of COVID-19: the behavioral immune system is associated with concern and preventative health behaviors. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0238015. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238015.

Alberti PM, Lantz PM, Wilkins CH. Equitable pandemic preparedness and rapid response: lessons from COVID-19 for pandemic health equity. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2020;45(6):921–35. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-8641469.

Higuera K. The privilege of social distancing. Contexts. 2020;19(4):22–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536504220977930.

Roberts JD, et al. Clinicians, cooks, and cashiers: examining health equity and the COVID-19 risks to essential workers. Toxicol Ind Health. 2020;36(9):689–702. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748233720970439.

Dubay L, Aarons J, Brown KS, Kenney GM. How risk of exposure to the coronavirus at work varies by race and ethnicity and how to protect the health and well-being of workers and their families. 2020;51.

Choi KH, Denice P, Haan M, Zajacova A. Studying the social determinants of COVID-19 in a data vacuum. Can Rev Sociol Can Sociol. 2021;58(2):146–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12336.

Poulson M, et al. National disparities in COVID-19 outcomes between Black and White Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113(2):125–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnma.2020.07.009.

Badenoch K. UK government’s work to tackle health disparities of covid-19. The BMJ. 2020;370. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2920

Coyer L, et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibody prevalence and correlates of six ethnic groups living in Amsterdam, the Netherlands: a population-based cross-sectional study, June–October 2020. BMJ Open. 2022;12(1):e052752. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052752.

Eades S, Eades F, McCaullay D, Nelson L, Phelan P, Stanley F. Australia’s first nations’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;396(10246):237–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31545-2.

Elizabeth McSheffrey. Premier faces backlash for singling out African Nova Scotian communities during COVID-19. Global News, Apr. 08, 2020. https://globalnews.ca/news/6793768/premier-faces-backlash-for-singling-out-african-nova-scotian-communities-during-covid-19/. Accessed 03 Jan 2022.

Kendi IX. Stop blaming black people for dying of the coronavirus. The Atlantic, Apr. 14, 2020. Available: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/04/race-and-blame/609946/. Accessed 01 May 2022.

Burnn C. Black health experts say surgeon general’s comments reflect lack of awareness of black community. NBC News, Apr. 15:2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/black-health-experts-say-surgeon-general-s-comments-reflect-lack-n1183711. Accessed 23 May 2022.

Lybrand H, Subramaniam T. Fact check: Texas lieutenant governor falsely implies Black people to blame for Covid surge. CNN Politics, Aug. 20, 2021. Available. https://www.cnn.com/2021/08/20/politics/texas-dan-patrick-coronavirus-black-people-vaccines-fact-check/index.html. Accessed 03 Jan 2022.

Banger C. Masks required at Black Lives matter solidarity march, but health officials worry COVID-19 could spread. CTV News, Jun. 02, 2020. https://kitchener.ctvnews.ca/masks-required-at-black-lives-matter-solidarity-march-but-health-officials-worry-covid-19-could-spread-1.4965776. Accessed 03 Jan 2022.

Nasser S. Brampton has emerged as one of Ontario’s COVID-19 hotspots, but experts urge caution on where to lay blame | CBC News. CBC, Sep. 14, 2020. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/brampton-coronavirus-covid-19-south-asian-1.5723330. Accessed 03 Jan 2022.

Bentley GR. Don’t blame the BAME: ethnic and structural inequalities in susceptibilities to COVID-19. Am J Hum Biol. 2020;32(5):e23478. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.23478.

Haley Ryan. Preston group upset premier singled community out for COVID-19 criticism. CBC News, Apr. 08, 2020. Available: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/preston-covid-19-premier-mcneil-nova-scotia-stigma-1.5526032. Accessed 03 Jan 2022.

Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X.

Rossiter J, Ndekezi T. Confronting racism with data: why canada needs disaggregated race-based data, Edmonton Social Planning Council, Edmonton, Alberta, Feb. 2021. Available: https://edmontonsocialplanning.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Race-Based-Data_ESPCFeatureReport_Feb2021.pdf

City of Toronto. “COVID 19: Ethno-Racial Identity & Income,” Toronto, ON. [Online]. Available: https://www.toronto.ca/home/covid-19/covid-19-pandemic-data/covid-19-ethno-racial-group-income-infection-data/

Torensma M, et al. Contextual factors that shape uptake of COVID-19 preventive measures by persons of Ghanaian and Eritrean origin in the Netherlands: a focus group study. J Migr Health. 2021;4:100070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmh.2021.100070.

Zhong B-L, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(10):1745–52. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.45221.

Kaliyaperumal K. Guideline for conducting a knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) study. AECS Illum. 2004;4:7–9.

Manderson L, Aaby P. An epidemic in the field? Rapid assessment procedures and health research. Soc Sci Med 1982. 1992;35(7):839–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(92)90098-b.

Ogochukwu, Ezennia Angelica, Geter Dawn K., Smith (2019) The PrEP Care Continuum and Black Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Scoping Review of Published Data on Awareness Uptake Adherence and Retention in PrEP Care. AIDS and Behavior 23(10) 2654-2673 10.1007/s10461-019-02641-2

Federica, Calò Antonio, Russo Clarissa, Camaioni Stefania, De Pascalis Nicola, Coppola (2020) Burden risk assessment surveillance and management of SARS-CoV-2 infection in health workers: a scoping review. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 9(1) 139 10.1186/s40249-020-00756-6

Ferdinand KC, Nasser SA. African-American COVID-19 Mortality: A Sentinel Event. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(21):2746–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.040.

Rusoja EA, Thomas BA. The COVID-19 pandemic Black mistrust and a path forward. EClinicalMedicine 2021; 35100868-S2589537021001486 100868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100868.

Andrea C., Tricco Erin, Lillie Wasifa, Zarin Kelly K., O'Brien Heather, Colquhoun Danielle, Levac David, Moher Micah D.J., Peters Tanya, Horsley Laura, Weeks Susanne, Hempel Elie A., Akl Christine, Chang Jessie, McGowan Lesley, Stewart Lisa, Hartling Adrian, Aldcroft Michael G., Wilson Chantelle, Garritty Simon, Lewin Christina M., Godfrey Marilyn T., Macdonald Etienne V., Langlois Karla, Soares-Weiser Jo, Moriarty Tammy, Clifford Özge, Tunçalp Sharon E., Straus (2018) PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 169(7) 467-473 10.7326/M18-0850

OECD Interactive Tool: International Comparisons — Peer countries, Canada, Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2022. https://www.cihi.ca/en/oecd-interactive-tool-international-comparisons-peer-countries-canada

Veritas Health Innovation. “Covidence systematic review software.” Melbourne, Australia. [Online]. Available: www.covidence.org

Deliz JR, Fears FF, Jones KE, Tobat J, Char D, Ross WR. Cultural competency interventions during medical school: a scoping review and narrative synthesis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(2):568–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05417-5.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version. 2006;1(1):92.

Helms JE. Some better practices for measuring racial and ethnic identity constructs. J Couns Psychol. 2007;54(3):235–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.235.

Alsan M, Stantcheva S, Yang D, Cutler D. Disparities in coronavirus 2019 reported incidence, knowledge, and behavior among US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e2012403–e2012403. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12403.

Bailey SC, et al. Changes in COVID-19 knowledge, beliefs, behaviors, and preparedness among high-risk adults from the onset to the acceleration phase of the US outbreak. J Gen Intern Med JGIM. 2020;35(11):3285–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-05980-2.

Lau LL, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of COVID-19 among income-poor households in the Philippines: a cross-sectional study. J Glob Health. 2020;10(1):011007. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.011007.

Jones et al. Similarities and differences in COVID-19 awareness, concern, and symptoms by race and ethnicity in the United States: cross-sectional survey. J Med Internet Res 2020;22(7). https://doi.org/10.2196/20001

Christensen SR, Pilling EB, Eyring JB, Dickerson G, Sloan CD, Magnusson BM. Political and personal reactions to COVID-19 during initial weeks of social distancing in the United States. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0239693–e0239693. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239693.

Gollust SE, Vogel RI, Rothman A, Yzer M, Fowler EF, Nagler RH. Americans’ perceptions of disparities in COVID-19 mortality: results from a nationally-representative survey. Prev Med. 2020;141:106278–106278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106278.

Alobuia WM, Dalva-Baird NP, Forrester JD, Bendavid E, Bhattacharya J, Kebebew E. Racial disparities in knowledge, attitudes and practices related to COVID-19 in the USA. J Public Health Oxf Engl. 2020;42(3):470–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa069.

O’Conor R, et al. Knowledge and behaviors of adults with underlying health conditions during the onset of the COVID-19 U.S. outbreak: the Chicago COVID-19 comorbidities survey. J Community Health. 2020;45(6):1149–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-020-00906-9.

Chen-Sankey JC, et al. Exploring changes in cigar smoking patterns and motivations to quit cigars among black young adults in the time of COVID-19. Addict Behav Rep. 2020;12:100317–100317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100317.

Bogart LM, et al. COVID-19 related medical mistrust, health impacts, and potential vaccine hesitancy among Black Americans living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2020;86(2):200–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0000000000002570.

Chandler R, et al. The impact of COVID-19 among Black women: evaluating perspectives and sources of information. Ethn Health. 2021;26(1):80–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2020.1841120.

Moore JT, et al. Disparities in incidence of COVID-19 among underrepresented racial/ethnic groups in counties identified as hotspots during June 5–18, 2020–22 States, February-June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(33):1122–6. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6933e1.

Ordaz-Johnson OH, Croff RL, Robinson LD, Shea SA, Bowles NP. More than a statistic: a qualitative study of COVID-19 treatment and prevention optimization for Black Americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(12):3750–2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06259-2.

Liu Y, Finch BK, Brenneke SG, Thomas K, Le PD. Perceived discrimination and mental distress amid the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from the understanding America study. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(4):481–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.007.

Chua K-P, DeJonckheere M, Reeves SL, Tribble AC, Prosser LA. Factors associated with school attendance plans and support for COVID-19 risk mitigation measures among parents and guardians. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21(4):684–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2020.11.017.

Gilbert LK, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in parental attitudes and concerns about school reopening during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, July 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(49):1848–52. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6949a2.

Guidry JPD, et al. Willingness to get the COVID-19 vaccine with and without emergency use authorization. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49(2):137–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.11.018.

Fisher KA, Bloomstone SJ, Walder J, Crawford S, Fouayzi H, Mazor KM. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(12):964–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-3569.

Malik AA, McFadden SM, Elharake J, Omer SB. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495.

Ruprecht MM, et al. Evidence of social and structural COVID-19 disparities by sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/ethnicity in an urban environment. J Urban Health. 2021;98(1):27–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-020-00497-9.

Sauceda JA, Neilands TB, Lightfoot M, Saberi P. Findings from a probability-based survey of United States households about prevention measures based on race, ethnicity, and age in response to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(10):1607–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa554.

Clipman SJ, et al. Rapid real-time tracking of non-pharmaceutical interventions and their association with SARS-CoV-2 positivity: the COVID-19 pandemic pulse study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1313.

Block R, Berg A, Lennon RP, Miller EL, Nunez-Smith M. African American adherence to COVID-19 public health recommendations. Health Lit Res Pract. 2020;4(3):e166–70. https://doi.org/10.3928/24748307-20200707-01.

Chunara R, et al. Telemedicine and healthcare disparities: a cohort study in a large healthcare system in New York City during COVID-19. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(1):33–41. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa217.

World Health Organization and S. T. Partnership, “Advocacy, communication and social mobilization for TB control: a guide to developing knowledge, attitude and practice surveys,” World Health Organization, WHO/HTM/STB/2008.46, 2008. Accessed: Mar. 26, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43790

Cho Lee, Wong Jieling, Chen Ka Ming, Chow Bernard M.H., Law Dorothy N.S., Chan Winnie K.W., So Alice W.Y., Leung Carmen W.H., Chan (2020) Knowledge Attitudes and Practices Towards COVID-19 Amongst Ethnic Minorities in Hong Kong. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17(21) 7878-10.3390/ijerph17217878

Millett GA, Peterson JL, Wolitski RJ, Stall R. Greater risk for HIV infection of black men who have sex with men: a critical literature review. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(6):1007–19. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.066720.

Clark HM. Who rides public transportation. 2017;86

Jaiswal J, LoSchiavo C, Perlman DC. Disinformation, misinformation and inequality-driven mistrust in the time of COVID-19: lessons unlearned from AIDS denialism. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(10):2776–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02925-y.

Ransing R, et al. Infectious disease outbreak related stigma and discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic: drivers, facilitators, manifestations, and outcomes across the world. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:555–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.033.

AlShurman BA, Khan AF, Mac C, Majeed M, Butt ZA. What demographic, social, and contextual factors influence the intention to use COVID-19 vaccines: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179342.

Maynard R. Policing Black lives : state violence in Canada from slavery to the present. Black Point, NS ; Winnipeg, Man.: Fernwood Publishing, 2017. Accessed: Dec. 19, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://e-artexte.ca/id/eprint/29596/

Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, Oliver MN. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113(16):4296–301. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516047113.

Alphonso C. TDSB data show rapid reading improvement in Black elementary students during COVID-19 pandemic. Globe and Mail, Aug. 31, 2021. Accessed: Jan. 03, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-tdsb-data-show-rapid-reading-improvement-in-black-elementary-students/

Reynolds R, Aromi J, McGowan C, Paris B. Digital divide, critical-, and crisis-informatics perspectives on K-12 emergency remote teaching during the pandemic. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol. 2022;73(12):1665–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24654.

Ahmed R, Jamal O, Ishak W, Nabi K, Mustafa N. Racial equity in the fight against COVID-19: a qualitative study examining the importance of collecting race-based data in the Canadian context. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines. 2021;7(1):15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40794-021-00138-2.

Airhihenbuwa CO. Culture matters in communicating the global response to COVID-19. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd17.200245.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study conception and design were performed by Fiqir Worku. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Fiqir Worku and Falan Bennett and overseen by Janet Papadakos. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Fiqir Worku, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This is a scoping review. Therefore, no ethical approval is required.

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was not required as there were no individual participants included in this paper.

Consent to Publish

Research participants were not included in this paper; therefore, informed consent for publication was not required.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Worku, F., Bennett, F., Wheeler, S. et al. Exploring the COVID-19 Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAPs) in the Black Community: a Scoping Review. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 11, 273–299 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01518-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-023-01518-4