Abstract

Background and Objectives

It is controversial whether hospital care mitigated or exacerbated population level racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality. To begin answering that question, this study analyzed variations in COVID-19 hospital mortality in Illinois by patient race and ethnicity and by hospital characteristics, while providing an estimate of hospital-level variation in COVID-19 mortality.

Method

This is a retrospective cohort study based on hospital administrative data for adult patients with COVID-19 discharged from acute care, non-federal Illinois hospitals from April 1, 2020 through June 30, 2021. The association of patient and hospital characteristics with the likelihood of death was analyzed using multilevel logistic regression.

Results

There were 158,569 COVID-19-coded admissions to 181 general hospitals in Illinois; 14.5% resulted in death or discharge to hospice. Hospital deaths accounted for nearly 90% of all COVID-19-associated deaths over 15 months in Illinois. After adjusting for patient- and hospital-level characteristics, Hispanic patients had higher mortality risk (aOR 1.26, 95% CI: 1.20–1.33) as compared with non-Hispanic White patients, while non-Hispanic Black patients had lower mortality risk (aOR 0.75, 95% CI: 0.71–0.79). Safety net hospitals receiving disproportionate share hospital (DSH) funds had higher mortality risk (aOR 1.81, 95% CI: 1.43–2.30) compared with other hospitals.

Conclusion

Risk-adjusted COVID-19 hospital mortality was highest among patients of Hispanic ethnicity, while non-Hispanic Black patients had lower risk than non-Hispanic White patients. There was significant variation in hospital mortality rates, with particularly high safety net hospital mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is well known that elevated risks of COVID-19 mortality are associated with social determinants of health in the USA [1,2,3]. Less clear is how hospital care mitigates or exacerbates sociodemographic disparities in COVID-19 outcomes. Retrospective cohort studies of COVID-19 hospital mortality early in the pandemic lent support to the conclusion that some hospitals helped equalize racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19 mortality [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. More recent studies based on data aggregated from multiple health systems and geographic locations found significant risk-adjusted differences in inpatient COVID-19 mortality between hospitals that may reinforce racial disparities [11,12,13]. But several of these studies were limited to patients on Medicare, thus underrepresenting younger age groups. Ambiguous findings throughout the pandemic led us to analyze variations in COVID-19 mortality in a large sample of hospitals across Illinois for all patients over age 18, examining data from the beginning of the pandemic through June 2021 that encompass nearly all statewide mortalities due to COVID-19 during this period.

This study presents findings from administrative hospital data for all COVID-19-coded hospitalizations at non-federal, general acute care hospitals which are members of the Illinois Hospital Association (IHA). We used data from adult patients discharged from April 1, 2020 to June 30, 2021, encompassing the pandemic spikes following the Illinois stay at home order period in March 2020 and including a second spike in the fall and winter of 2020–2021. Using a multilevel logistic regression model, we tested the significance of associations between patient- and hospital-level characteristics and hospital COVID-19 mortality. The aims of the study were to (1) describe adult COVID-19 mortality rates across acute care Illinois hospitals over different periods of the pandemic; (2) test the significance of associations between COVID-19 mortality and patient sociodemographic characteristics, in particular race and ethnicity; (3) test the significance of differences in COVID-19 mortality rates by hospital characteristics; and (4) quantify the relative contribution of patient-level versus hospital-level differences to the overall variance in hospital COVID-19 mortality.

Methods

Data Sources

We performed a retrospective cohort study using the Illinois Hospital Association Comparative Health Care and Hospital Data Reporting Services Database (COMPdata), which includes administrative data on all inpatient visits to Illinois Hospital Association hospitals. We identified all hospital admissions that included COVID-19 as a principal or secondary diagnosis for which discharges occurred between April 1, 2020 and June 30, 2021. The International Classification of Diseases 10th edition (ICD10) diagnostic code U07.1 was used to capture principal and secondary diagnoses of COVID-19. All data were publicly available and deidentified, and our study was institutional review board exempt at Northwestern University.

Patient, Hospital, and Time Period Characteristics

Patients under age 18 were excluded from the analysis consistent with prior COVID-19 mortality studies [4, 6, 14], as pediatric manifestations of COVID-19 have significantly lower inpatient mortality rates than adults (0.6% in our sample). Patient sociodemographic characteristics included in the analysis were age group (18–45, 46–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75, or older), sex (male or female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Asian, or other/unknown), and primary insurance coverage (private, Medicare age over 65, Medicare disability, Medicaid, uninsured, or other/unknown). The “other/unknown” category of race/ethnicity consisted of three identified race/ethnic categories of Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and Multi-racial (2.0% of total admissions) and those who declined to identify a racial category or identified in an “other” category (4.1% of total admissions).

We matched patient zip codes to 2019 American Community Survey 5-year zip code census tabulation area (ZCTA) data for the percent of households in each patient’s ZCTA living at or below the federal poverty level. We categorized patients’ ZCTA poverty levels as < 5%, 5 to 9.99%, 10 to 19.99%, ≥ 20%, or non-Illinois resident. Counties of residence were grouped as Cook, which included the city of Chicago; Chicago metro area “collar” counties of Will, Kane, Lake, DuPage, and McHenry; and “downstate” which included all remaining Illinois counties as well as a small number (2.0%) of non-Illinois residents hospitalized at Illinois institutions. Consistent with prior studies, we combined death and discharge to hospice to avoid exaggerating racial/ethnic differences in mortality rates due to higher rates of utilizing “do not resuscitate” orders among non-Hispanic White patients compared with Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black patients [11, 12].

Patient clinical characteristics included whether COVID-19 was a principal versus secondary diagnosis and whether the admission was a transfer from another hospital or a skilled nursing facility. Patient comorbid conditions were classified by the Charlson comorbidity score based on the weighted presence of ICD-10 codes for 20 chronic comorbid conditions (categorized as scores from 0 to 6 or more) [15]. Reflecting pandemic waves, timing of discharge was divided into four periods (April to June 2020, July to November 2020, December 2020 to February 2021, and March to June 2021).

We included only patients admitted to general acute care hospitals, so admissions to long-term care facilities or specialty hospitals such as rehabilitation or behavioral health facilities (accounting for 2.8% of all COVID-19-coded admissions) were excluded. The general hospitals included in the analysis were separated into four bed count categories (< 100, 100–349, ≥ 350, or unknown) using data from the Illinois Hospital Report Card and Consumer Guide to Health Care [16]. We analyzed hospital bed count as the structural proxy for COVID-19 admission volume, as hospital bed count and COVID-19 admission volume were correlated with a Pearson’s correlation coefficient of 0.85. Hospital safety net status was classified based on the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services (HFS) Annual Safety Net Hospital Determination as of October 1, 2020. This classification applied to all Disproportionate Share Hospitals (DSH) that had a Medicaid inpatient utilization rate (MIUR) of at least 50% or an MIUR of 40% and a charity care percent of at least 4% [17]. Public hospitals and hospitals which are members of the American Academy of Medical Colleges Council of Teaching Hospitals and Health Systems (COTH), found on the AAMC hospitals and health system registry [18], were classified as “public/COTH” hospitals [19]. All other hospitals were characterized as acute care community hospitals.

Statistical Analysis

We compared in-hospital COVID-19 mortality rates for all categories defined above using univariate χ2 tests. A multilevel logistic regression model was chosen to test associations of patient- and hospital-level factors with in-hospital COVID-19 mortality. The multilevel or hierarchical model has several advantages over ordinary logistic regression, chief among which is that it explicitly accounts for clustering of individuals within groups (i.e., patients within hospitals). It thus avoids the erroneous assumption of the independence of within-group observations and the type I error that thereby results [20].

We first fit the multilevel null model without any predictors to determine the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), a value between 0 and 1 that quantifies the proportion of outcome variance explained by between-group variance. Patient-level factors were then added in Model 1, followed by hospital-level factors (Model 2), generating two nested random-intercept models. Known risk factors constituted fixed effects in the model, which were reported as adjusted odds ratios (aOR). Improvements in fit from the null model to Model 2 were estimated by the subsequent reduction in residual ICC. The likelihood-ratio χ2 test was also done to quantify improvement in model fit, with improvement defined by a p-value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 16.1, College Station, TX.

Results

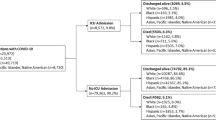

Out of 165,293 total COVID-19 admissions, 4646 admissions from non-acute hospitals and 2078 admissions of pediatric patients were excluded. The remaining 181 non-federal general acute care hospitals in this study saw between two and 5809 admissions of adult patients with COVID-19 over the study period (mean = 876, SD = 1014) for a total of 158,569 admissions. Over the 15-month study period, 17,838 (11.2%) admissions resulted in death, and another 5189 (3.3%) resulted in discharge to hospice for a composite 14.5% mortality outcome.

Figure 1 displays monthly admissions, intensive care unit (ICU) use, and deaths or hospice discharges, with a peak of over 35,000 admissions in December 2020 and January 2021. Monthly mortality rates were highest in April 2020 (20.0%) declining to 17.9% in June 2020 and peaking again in the second wave in December 2020 (16.7%) and January 2021 (15.2%).

Patient Mortality Rates

Table 1 presents patient, hospital, and time period differences in death rates. Mortality increased with age, with a mortality rate of 26.7% for admissions of patients age 75 and over compared to 2.4% for patients age 18–45. A majority of admissions were for non-Hispanic White (51.0%) patients and non-Hispanic White patients had the highest unadjusted in-hospital mortality rate (16.3%) of any racial or ethnic group. In comparison, non-Hispanic Black patients had the lowest unadjusted hospital mortality rate (11.9%).

Admissions of patients transferred from other hospitals or skilled nursing facilities had a high mortality rate of 28.3%, as did admissions for which COVID-19 was a secondary diagnosis (19.8%). There was a monotonic increase in COVID-19 mortality risk with increasing Charlson comorbidity score, spanning a rate of 5.7% for a Charlson comorbidity score of 0 to 26.6% for comorbidity scores of 6 and over. Mortality was highest during the first period of the pandemic (19.1%) and lowest in the last period from March 2021 to June 2021 (10.1%).

Hospital Mortality Rates

Out of 181 hospitals, 89 (49.2%) had fewer than 100 beds, 77 (42.5%) had between 100 and 349 beds, 11 (6.1%) had 350 or more beds, and 4 (2.2%) had an unknown bed count.

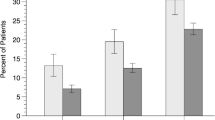

Twenty five (14.4%) met Illinois state criteria of safety net hospital and 15 (7.7%) were public hospitals and/or members of COTH. Hospitals with between 100 and 349 beds had a higher mortality rate (15.2%) than hospitals with fewer than 100 beds (12.7%). Community hospitals had a higher mortality rate (14.5%) than public/COTH hospitals (13.1%), and safety net hospitals had a higher mortality rate (18.1%) than both. Figure 2 compares the distribution of hospital COVID-19 mortality rates for all three types of hospitals.

Multilevel Logistic Regression Results

The null model, which included only hospital-level random effects, had an estimated intercept of − 2.03 and hospital-level variance of 0.39, corresponding to a hospital-level average mortality probability of 0.12 (95% CI: 0.08–0.16). The range of hospital COVID-19 mortality rates was 0–33.3%. Overall hospital mortality rates decreased after the initial wave of COVID-19, as patients who were discharged from April to June 2020 had around 27–39% higher adjusted odds of mortality than those discharged during subsequent periods.

The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of the null model was 0.11 (95% CI: 0.08–0.14). Thus an estimated 11% of total variance in mortality is attributable to between-hospital variance. Compared with the null model, Model 1 had a negligibly reduced ICC (from 0.11 to 0.10). Table 2 shows the Model 1 adjusted odds ratios of death or discharge to hospice and Model 2 including hospital-level factors. Adding hospital-level characteristics did little to modify patient-level effects, with the exception of the lower odds ratio associated with residence in downstate IL compared with Cook County in Model 1 (aOR 0.86, 95% CI: 0.77–0.97), which was no longer statistically significant in Model 2 (aOR 0.97, 95% CI: 0.87–1.09). Model fit improved from Model 1 to Model 2 (χ2 = 60.8, p-value < 0.001) with the addition of hospital characteristics, resulting in a 30% reduction in residual ICC from 0.10 to 0.07.

In the final Model 2, non-Hispanic Black patients had lower odds of mortality than non-Hispanic White patients (aOR 0.75, 95% CI: 0.71–0.79) while Hispanic patients had higher odds of mortality (aOR 1.26, 95% CI: 1.20–1.33). A small monotonic increase in mortality risk was associated with increased poverty in the patient’s residential ZCTA. There was no significant difference in mortality risk between patients with Medicaid and those with private insurance. Admissions of uninsured patients had 17% higher adjusted odds of mortality compared with privately insured patients.

Compared to hospitals with fewer than 100 beds, admissions to hospitals with more than 100 beds were associated with higher odds of mortality (aOR 1.77, 95% CI: 1.46–2.14 for hospitals with 100–349 beds; aOR 1.85, 95% CI: 1.19–2.89 for hospitals with 350 beds or more). As compared to community hospitals, IL state safety net status was associated with a mortality aOR of 1.81 (95% CI: 1.43–2.30), while public hospitals and COTH members were not associated with significantly increased mortality.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine nearly all deaths of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in a single US state. Our sample included 23,037 deaths and discharges to hospice, encompassing approximately 89.8% of the cumulative statewide total deaths (25,660) from the start of the pandemic to June 30, 2021 [21]. Over this period, the hospital mortality rate improved from 19.1% during the first 3 months of the pandemic to 10.1% during the last 4 months of the study period with a rise during the winter surge to 16.1% from December 2020 to February 2021. A similar decrease in hospital mortality rate from 19.1% in March and April 2020 to 11.9% by June 2020 has been reported in a national sample of hospitalized patients [14], attributed in part to the relief of overwhelmed hospitals and to increasingly widespread use of remdesivir, dexamethasone, noninvasive ventilation, patient proning, and vaccines.

Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black both patients experienced a disproportionately higher burden of COVID-19-related hospitalizations in our sample, making up 18.1% and 20.7% of total admissions, respectively, while accounting for only 17.5% and 14.6% and of the state population. This finding is consistent with higher population rates of COVID-19 disease and death experienced by these two groups in Illinois and nationwide [21, 22]. After risk adjustment in our model, the association between minority race and ethnicity and hospital COVID-19 mortality partially confirmed prior findings. Patients of Hispanic ethnicity had 27% higher adjusted odds of hospital COVID-19 mortality than non-Hispanic White patients, consistent with national samples [12, 23]. The lower mortality odds of non-Hispanic Black versus non-Hispanic White patients is corroborated in one study based on a single health system in New York City, which found 30% lower adjusted odds of in-hospital COVID-19 mortality for Black patients [6], whereas studies that aggregated data from multiple health systems suggested that Black patients nationwide experienced higher [11, 12] or similar [23] odds of mortality compared with hospitalized White patients.

A possible explanation for the lower risk of hospital mortality for non-Hispanic Black patients in our study is their comparatively high rates of hospitalization in Illinois. As of October 2021, the COVID-19 case rate ratio between Black and White residents of Illinois is around 1.1 (using a non-Hispanic White population percentage of 60.8%) whereas the rate ratio of hospitalization between non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White patients in our study sample is 1.7 [22, 24]. Hispanic Illinoisans, on the other hand, have a population case rate of COVID-19 that is 1.6 times higher than non-Hispanic White Illinoisans, but only a 1.3 times higher rate of hospitalization in our sample [22, 24]. Even though Black patients in Illinois appear to be hospitalized at a higher rate than Hispanic and non-Hispanic White patients, we cannot exclude the concomitant possibility of high rates of out-of-hospital mortality for Black patients with severe COVID-19, which could artificially depress their rates of in-hospital mortality [25, 26].

Disaggregating the effects of individual and institutional risk factors is always an analytical challenge, but we have reasons to believe that our findings on the relative importance of hospital characteristics are robust. Around 11% of the variance in mortality outcomes can be attributed to interhospital variance, which was not significantly reduced with the addition of patient-level risk factors in Model 1. The addition of hospital-level fixed effects in Model 2 accounted for about 30% of the interhospital variation in mortality without significantly modifying patient-level effects.

The role of differences in hospital quality of care remains an important topic for future research. One study based on a national sample of Medicare Advantage patients showed that hospital-level factors significantly attenuated mortality risk differences between Black and White patients [11]. The evidence in this study is consistent with both an unequal burden of patient-level COVID-19 mortality risk factors across Illinois hospitals and disparities in hospital care quality. It is possible that unmeasured case mix differences, for instance COVID-19 severity at admission, explain at least a part of the elevated adjusted mortality odds associated with admissions to hospitals with more than 100 beds. Even after accounting for transfers, larger hospitals may have admitted a larger share of patients with more severe disease, thus showing 77–85% higher odds of hospital COVID-19 mortality than hospitals with less than 100 beds.

Safety net hospitals cared for around 10% of all admissions and patients hospitalized at safety net institutions had over 80% higher odds of COVID-19 mortality compared with non-safety nets. Out of 25 safety net hospitals, 15 were in the 100–349 bed count category. Non-Hispanic Black (30.3%) and Hispanic (27.6%) patients combined made up the majority of COVID-19 admissions to safety net hospitals, compared with only 19.5% of admissions to community hospitals. Uninsured patients also made up a larger share of admissions to safety nets (7.3%) compared with community hospitals (3.5%). While public and/or COTH member hospitals also disproportionately cared for racial/ethnic minority patients (non-Hispanic Black 29.0%, Hispanic 26.6%), COTH/public hospital status was not associated with increased mortality risk compared to community hospitals. This suggests that case mix differences alone do not explain the elevated mortality odds at state safety net hospitals.

Comparable findings have been reported in a study examining the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of risk adjusted outcomes for patients admitted with myocardial infarction, pneumonia, and heart failure in a national sample of hospitals [27]. Although limited by the lack of diversity in a large share of US hospitals that had to be excluded from the analysis, the study found that patients of different race/ethnic and socioeconomic groups within the same hospital experienced similar outcomes, and that between-hospital differences were not associated with patient mix differences. The authors concluded that disparities in outcomes were related to systemic factors that affected all hospitals. Likewise, we found that interhospital variations in COVID-19 mortality in the state of Illinois do not appear to be fully explained by the distribution of patient-level risk factors.

However, our study also shows that in the case of COVID-19, systemic factors associated with racial/ethnic disparities in patient outcomes that affect all hospitals can coexist with higher mortality risk associated with specific types of hospitals. Other studies have found that site of hospital care does correlate with inpatient quality of care measures and maternal morbidity outcomes that disproportionately affect racial and ethnic minorities [28, 29]. In the case of COVID-19 in Illinois, even if racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes cannot be fully mitigated by measures localized to a small subset of hospitals, supporting safety net hospitals in Illinois through improved public funding beyond existing DSH payments remains a cost-effective way to improve outcomes for a subset of vulnerable patients.

Although this study provides a rare state population-based analysis, the lack of detailed clinical data, for instance for body mass index, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and pulmonary infiltrates at admission, limits accurate risk adjustment. We were unable to link multiple admissions of the same patients. Bed count is also a relatively crude measure of hospital capacity. Future studies of variation in hospital death rates should include more detailed analyses of COVID-19 specific resource capacities, such as nurse staffing ratios, number of critical care specialists, ventilators, and ICU beds.

In summary, our study adds to the evidence that there is a significant degree of variability in COVID-19 mortality rates between patients of different race/ethnic groups and between hospitals even after adjusting for individual patient characteristics. Hospital characteristics significantly associated with higher hospital COVID-19 mortality risk included bed count and safety net status as defined by Illinois state DSH payment eligibility and inpatient Medicaid utilization rate. To achieve a more equitable pandemic response, policies to reduce repeated duress over pandemic surges will require ramping up support for safety net hospitals already under considerable resource constraint.

References

Chen JTS, Krieger N. Revealing the unequal burden of COVID-19 by income, race/ethnicity, and household crowding: US county versus zip code analyses. J Public Health Manag. 2021;27:S43–56.

Quan D, Luna Wong L, Shallal A, et al. Impact of race and socioeconomic status on outcomes in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(5):1302–9.

Feldman JM, Bassett MT. Variation in COVID-19 mortality in the US by race and ethnicity and educational attainment. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(11):e2135967.

Gold JAW, Wong KK, Szablewski CM, et al. Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes of Adult Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19 - Georgia, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. May 8 2020;69(18):545-550. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6918e1

Azar KMJ, Shen Z, Romanelli RJ, et al. Disparities in outcomes among COVID-19 patients in a large health care system in California. Health Aff. 2020;39(7):1253–62.

Ogedegbe G, Ravenell J, Adhikari S, et al. Assessment of racial/ethnic disparities in hospitalization and mortality in patients with COVID-19 in New York City. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2026881–e2026881.

Price-Haywood EG, Burton J, Fort D, Seoane L. Hospitalization and mortality among black patients and white patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(26):2534–43.

Renelus BD, Khoury NC, Chandrasekaran K, et al. Racial disparities in COVID-19 hospitalization and in-hospital mortality at the height of the New York City pandemic. J Racial Ethnic Health Disparities. 2020;8(5):1161–7.

Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052–9.

Yehia BR, Winegar A, Fogel R, et al. Association of race with mortality among patients hospitalized with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) at 92 US hospitals. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(8):e2018039.

Asch DA, Islam MN, Sheils NE, et al. Patient and hospital factors associated with differences in mortality rates among black and white US Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with COVID-19 infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2112842–e2112842.

Qureshi AI, Baskett WI, Huang W, et al. Effect of race and ethnicity on in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19. Ethn Dis. 2021;31(3):389–98.

Churpek MM, Gupta S, Spicer AB, et al. Hospital-level variation in death for critically ill patients with COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;04:403–11.

Roth GA, Emmons-Bell S, Alger HM, et al. Trends in patient characteristics and COVID-19 in-hospital mortality in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e218828.

Sundararajan V, Henderson T, Perry C, Muggivan A, Quan H, Ghali WA. New ICD-10 version of the Charlson comorbidity index predicted in-hospital mortality. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(12):1288–94.

Illinois Department of Public Health. Illinois Hospital Report Card and Consumer Guide to Health Care. 2021; http://www.healthcarereportcard.illinois.gov/. Accessed December 7, 2021.

Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services. Healthcare and Family Services Safety Net Hospital Determination Effective 10/1/2020 ‐ 9/30/2021. 2021.

American Association of Medical Colleges. AAMC Hospital/Health System Members. 2021; https://members.aamc.org/eweb/DynamicPage.aspx?site=AAMC&webcode=AAMCOrgSearchResult&orgtype=Hospital/Health%20System. Accessed November, 10, 2021.

McHugh M, Kang R, Hasnain-Wynia R. Understanding the safety net: inpatient quality of care varies based on how one defines safety-net hospitals. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(5):590–605.

Sanagou M, Wolfe R, Forbes A, Reid CM. Hospital-level associations with 30-day patient mortality after cardiac surgery: a tutorial on the application and interpretation of marginal and multilevel logistic regression. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:28.

Lilly D, Akintorin S, Unruh LH, Dharmapuri S, Soyemi K. Years of potential life lost secondary to COVID-19: Cook County, Illinois. Ann Epidemiol. 2021;58:124–7.

Kaiser Family Foundation. COVID-19 Cases by Race/Ethnicity. 2021; https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/covid-19-cases-by-race-ethnicity/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D. Accessed January 10, 2022.

Song Z, Zhang X, Patterson LJ, Barnes CL, Haas DA. Racial and ethnic disparities in hospitalization outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(12):e214223–e214223.

United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts Illinois. 2021; https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/IL. Accessed December 16, 2021.

Pathak EB, Garcia RB, Menard JM, Salemi JL. Out-of-hospital COVID-19 deaths: consequences for quality of medical care and accuracy of cause of death coding. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(S2):S101–6.

Rossen LM, Ahmad FB, Anderson RN, et al. Disparities in excess mortality associated with COVID-19 — United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(33):1114–9.

Downing NS, Wang C, Gupta A, et al. Association of racial and socioeconomic disparities with outcomes among patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia: an analysis of within- and between-hospital variation. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(5):e182044.

Howell EA, Egorova NN, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Site of delivery contribution to black-white severe maternal morbidity disparity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215(2):143–52.

Hasnain-Wynia R, Baker DW, Nerenz D, et al. Disparities in health care are driven by where minority patients seek care: examination of the hospital quality alliance measures. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1233–9.

Acknowledgements

We thank William Trick, MD of Cook County Health for his valuable comments on an earlier version of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hua, M.J., Feinglass, J. Variations in COVID-19 Hospital Mortality by Patient Race/Ethnicity and Hospital Type in Illinois. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 10, 911–919 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01279-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01279-6