Abstract

Background

In 2016, black women with HIV infection attributed to heterosexual contact accounted for 47% of all women living with diagnosed HIV, and 41% of deaths that occurred among women with diagnosed HIV in the USA that year. Social determinants of health have been found to be associated with mortality risk among people with HIV. We analyzed the role social determinants of health may have on risk of mortality among black women with HIV attributed to heterosexual contact.

Methods

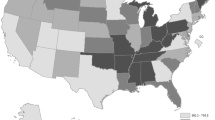

Data from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s National HIV Surveillance System were merged at the county level with three social determinants of health (SDH) variables from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey for black women aged ≥ 18 years with HIV infection attributed to heterosexual contact that had been diagnosed by 2011. SDH variables were categorized into four empirically derived quartiles, with the highest quartile in each category serving as the reference variable. For black women whose deaths occurred during 2012–2016, mortality rate ratios (MRR) were calculated using age-stratified multivariate logistic regressions to evaluate associations between SDH variables and all-cause mortality risk.

Results

Risk of mortality was lower for black women aged 18–34 years and 35–54 years who lived in counties with the lowest quartile of poverty (adjusted mortality rate ratio aMRR = 0.56, 95% confidence interval CI [0.39–0.83], and aMRR = 0.67, 95% CI [0.58–0.78], respectively) compared to those who lived in counties with the highest quartile of poverty (reference group). Compared to black women who lived in counties with the highest quartile of health insurance coverage (reference group), the mortality risk was lower for black women aged 18–34 years and black women aged 35–54 who lived in counties with the lowest 2 quartiles of health insurance coverage. Unemployment status was not associated with mortality risk.

Conclusions

This ecological analysis found poverty and lack of health insurance to be predictors of mortality, suggesting a need for increased prevention, care, and policy efforts targeting black women with HIV who live in environments characterized by increased poverty and lack of health insurance.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, vol. 29. 2017. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/surveillance/. Published November 2018. Accessed 8 Jan 2019.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). NCHHSTP AtlasPlus. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/atlas/. Accessed 8 Jan 2019.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 dependent areas, 2016. HIV Surveillance Supplemental Report 2018;23 (No. 4). http://wwwcdcgov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillancehtml Published July 2017. Accessed 8 Jan 2019.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health among adults with diagnosed HIV infection, 2016. Part B: county-level social determinants of health and selected care outcomes among adults with diagnosed HIV infection—39 states and the District of Columbia. HIV Surv Suppl Rep. 2018;23(No. 6, pt B). http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published October 2018. Accessed 8 Jan 2019.

Moore RD. Epidemiology of HIV infection in the United States: implications for linkage to care. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(suppl_2):S208–13.

Aziz M, Smith KY. Challenges and successes in linking HIV-infected women to care in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(suppl_2):S231–7.

World Health Organization, Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Available from: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/en. Accessed 8 Jan 2019.

Dean HD, Fenton KA. Addressing social determinants of health in the prevention and control of HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted infections, and tuberculosis. Public Health Rep. 2010;4:1–4.

Ansari Z, Carson NJ, Ackland MJ, Vaughan L, Serraglio A. A public health model of the social determinants of health. Sozial-und Präventivmedizin/Social and Preventive Medicine. 2003;48(4):242–51.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Social determinants of health among adults with diagnosed HIV infection, 2016. Part A: Census tract-level social determinants of health among adults with diagnosed HIV infection—13 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. HIV Surv Suppl Rep. 2018;23(No. 6, pt A). http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html. Published October 2018. Accessed 8 Jan 2019.

Gant Z, Lomotey M, Hall HI, Hu X, Guo X, et al. A county-level examination of the relationship between HIV and social determinants of health: 40 states, 2006-2008. Open AIDS J. 2012;6:1.

Gant Z, Gant L, Song R, Willis L, Johnson AS. A census tract–level examination of social determinants of health among black/African American men with diagnosed HIV infection, 2005–2009—17 US areas. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e107701.

Wiewel EW, Bocour A, Kersanske LS, Bodach SD, Xia Q, Braunstein SL. The association between neighborhood poverty and HIV diagnoses among males and females in New York City, 2010–2011. Public Health Rep. 2016;131(2):290–302.

Reilly KH, Neaigus A, Jenness SM, Hagan H, Wendel T, Gelpí-Acosta C. High HIV prevalence among low-income, black women in New York City with self-reported HIV negative and unknown status. J Women's Health. 2013;22(9):745–54.

Sheehan DM, Trepka MJ, Fennie KP, Prado G, Madhivanan P, Dillon FR, et al. Individual and neighborhood predictors of mortality among HIV-positive Latinos with history of injection drug use, Florida, 2000–2011. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;154:243–50.

McMahon J, Wanke C, Terrin N, Skinner S, Knox T. Poverty, hunger, education, and residential status impact survival in HIV. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(7):1503–11.

Singh GK, Azuine RE, Siahpush M. Widening socioeconomic, racial, and geographic disparities in HIV/AIDS mortality in the United States, 1987–2011. Adv Prev Med. 2013;2013:1–13.

Harrison KM, Ling Q, Song R, Hall HI. County-level socioeconomic status and survival after HIV diagnosis, United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(12):919–27.

Cunningham WE, Hays RD, Duan N, Andersen R, Nakazono TT, Bozzette SA, et al. The effect of socioeconomic status on the survival of people receiving care for HIV infection in the United States. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16(4):655–76.

U.S. Census Bureau. A compass for understanding and using American Community Survey Data: what general data users need to know. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2008. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2008/acs/ACSGeneralHandbook.pdf. Accessed 24 Aug 2017

U.S. Census Bureau. American community survey multiyear accuracy of the data (5-year 2012-2016). https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/code-lists.2016.html. Accessed 8 Feb 2019.

Rubin MS, Colen CG, Link BG. Examination of inequalities in HIV/AIDS mortality in the United States from a fundamental cause perspective. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(6):1053–9.

Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;35:80–94.

Maruthappu M, Da Zhou C, Williams C, Zeltner T, Atun R. Unemployment, public–sector health care expenditure and HIV mortality: an analysis of 74 countries, 1981–2009. J Glob Health. 2015;5(1).

Bernell SL, Shinogle JA. The relationship between HAART use and employment for HIV-positive individuals: an empirical analysis and policy outlook. Health Policy. 2005;71(2):255–64.

Pellowski JA, Kalichman SC, Matthews KA, Adler N. A pandemic of the poor: social disadvantage and the US HIV epidemic. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):197–209.

Schwarcz SK, Hsu LC, Vittinghoff E, Vu A, Bamberger JD, Katz MH. Impact of housing on the survival of persons with AIDS. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):220.

Lieb S, Brooks RG, Hopkins RS, Thompson D, Crockett LK, Liberti T, et al. Predicting death from HIV/AIDS: a case-control study from Florida public HIV/AIDS clinics. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30(3):351–8.

Bhattacharya J, Goldman D, Sood N. The link between public and private insurance and HIV-related mortality. J Health Econ. 2003;22(6):1105–22.

Yehia BR, Fleishman JA, Metlay JP, Moore RD, Gebo KA. Sustained viral suppression in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy. JAMA. 2012;308(4):339–42.

Yehia BR, Fleishman JA, Hicks PL, Ridore M, Moore RD, Gebo KA. Inpatient health services utilization among HIV-infected adult patients in care 2002–2007. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53(3):397–404.

Ludema C, Cole SR, Eron JJ Jr, Edmonds A, Holmes GM, Anastos K, et al. Impact of health insurance, ADAP, and income on HIV viral suppression among US women in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study, 2006–2009. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73(3):307–12.

Schrimshaw EW, Siegel K. Perceived barriers to social support from family and friends among older adults with HIV/AIDS. J Health Psychol. 2003;8(6):738–52.

Emlet CA. An examination of the social networks and social isolation in older and younger adults living with HIV/AIDS. Health Soc Work. 2006;31(4):299–308.

Song R, Hall HI, Harrison KM, Sharpe TT, Lin LS, Dean HD. Identifying the impact of social determinants of health on disease rates using correlation analysis of area-based summary information. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(3_suppl):70–80.

Krieger N, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV. Monitoring socioeconomic inequalities in sexually transmitted infections, tuberculosis, and violence: geocoding and choice of area-based socioeconomic measures—the public health disparities geocoding project (US). Public Health Rep. 2003;118(3):240–60.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. DHAP Strategic Plan. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/dhap/strategicplan/. Updated July 2017. Accessed 4 Aug 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Animal and Human Studies

No animal or human studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Watson, L., Gant, Z., Hu, X. et al. Exploring Social Determinants of Health as Predictors of Mortality During 2012–2016, Among Black Women with Diagnosed HIV Infection Attributed to Heterosexual Contact, United States. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 6, 892–899 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-019-00589-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-019-00589-6