Abstract

Purpose

Black/African American (AA) infants have been persistently observed with survival disadvantage compared to White infants in the USA, implying excess mortality. While reliable epidemiologic data continue to illustrate these disparities, data are yet to provide a substantial explanation to the observed rates and risk differences over the past six decades. We aimed in this study to examine the infant mortality risk differences by temporal trends and to provide an ecologic and non-concurrent explanation for the persisted variability.

Methods

A retrospective design with aggregate data from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was used to access the risk difference in cause-specific mortality, while stratification analysis was utilized for the risk ratio estimation. We also estimated the percent change for mortality trends.

Results

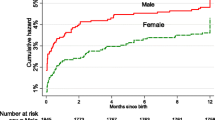

The cumulative infant mortality (IM) incidence was two times as likely for Black/AA relative to White, risk ratio (RR), 2.05. There were temporal trends in IM between 1968 and 2015 with excess IM among Black/AA children. Specifically, between 1968 and 2015, the percent change (% change) for digestive system disorders (58.43%); genito-urinary tract system disorders (58.20%); muscle, skeleton, and connective tissue disorders (66.60%); congenital anomalies (23.79%); and certain perinatal causes (38.65%) indicated upward trends in infant mortality Black/AA and White risk ratio. Except for neoplasm, and the initial study period (1968–1978) for congenital anomalies, Black/AA infants indicated survival disadvantage, implying excess mortality ratio relative to their White counterparts.

Conclusion

Disease-specific infant mortality is higher among black/AA except for neoplasm, and increasing percent changes are observed in digestive; genito-urinary; and muscle, skeleton, and connective tissue disorders. These findings are suggestive of the pressing needs to examine the cause of these disparities namely social determinants of health and social inequity for specific risk-adapted intervention in achieving health equity in US infant mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AA:

-

African American

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- NCHS:

-

National Center for Health Statistics

- OMB:

-

Office of Management and Budget

- PRA:

-

Paperwork Reduction Act

- SIDS:

-

Sudden infant death syndrome

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

US Central Intelligence Agency. US and Global Infant Mortality Ranking, 2017: Available at: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2091rank.html. Accessed 3/14/2018.

Hoyert, D. L., & Xu, J. (2012). Deaths: preliminary data for 2011. National Vital Statistics Reports, 61(6). Retrieved July 23, 2013, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_06.pdf (PDF - 891 KB.

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095–128.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) (2013) GBD 2010 change in leading causes and risks between 1990 and 2010. Retrieved November 5, 2014, from http://vizhub.healthdata.org/irank/arrow.php External Web Site Policy.

Mathews TJ, MacDorman MF. Infant mortality statistics from the 2006 period linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010 Apr 30;58(17):1–31.

Zeitlin J, El Ayoubi M, Jarreau PH, Draper ES, Blondel B, Künzel W, Cuttini M, Kaminski M, Gortner L, Van Reempts P, Kollée L, Papiernik E; MOSAIC Research Group. Impact of fetal growth restriction on mortality and morbidity in a very preterm birth cohort. J Pediatr 2010 Nov;157(5):733–9.e1. Epub 2010 Jun 17.

Reddy UM, Laughon SK, Sun L, Troendle J, Willinger M, Zhang J. Prepregnancy risk factors for antepartum stillbirth in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Nov;116(5):1119–26.

Ananth CV, Basso O. Impact of pregnancy-induced hypertension on stillbirth and neonatal mortality. Epidemiology. 2010 Jan;21(1):118–23.

Henriksen TB, Hjollund NH, Jensen TK, Bonde JP, Andersson AM, Kolstad H, et al. Alcohol consumption at the time of conception and spontaneous abortion. Am J Epidemiol. 2004 Oct 1;160(7):661–7.

Wikström AK, Cnattingius S, Stephansson O. Maternal use of Swedish snuff (snus) and risk of stillbirth. Epidemiology. 2010 Nov;21(6):772–8.

Mantakas A, Farrell T. The influence of increasing BMI in nulliparous women on pregnancy outcome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010 Nov;153(1):43–6. Epub 2010 Aug 21

Brocklehurst P, French R. The association between maternal HIV infection and perinatal outcome: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998 Aug;105(8):836–48.

Larson E, Hart L, Rosenblatt R. Is non-metropolitan residence a risk factor for poor birth outcome in the U.S.? Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(2):171–88.

Singh GK, Kogan MD. Persistent socioeconomic disparities in infant, neonatal, and postneonatal mortality rates in the United States, 1969–2001. Pediatrics. 2007 Apr;119(4):e928–39.

Scholer SJ, Hickson GB, Ray WA. Sociodemographic factors identify US infants at high risk of injury mortality. Pediatrics. 1999 Jun;103(6 Pt 1):1183–8.

Kitsantas P, Gaffney KF. Racial/ethnic disparities in infant mortality. J Perinat Med. 2010;38(1):87–94.

Alexander GR, Wingate MS, Bader D, Kogan MD. The increasing racial disparity in infant mortality rates: composition and contributors to recent US trends. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008 Jan;198(1):51.e1–9.

Besculides M, Laraque F. Racial and ethnic disparities in perinatal mortality: applying the perinatal periods of risk model to identify areas for intervention. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005 Aug;97(8):1128–32.

Hessol NA, Fuentes-Afflick E. Ethnic differences in neonatal and postneonatal mortality. Pediatrics. 2005 Jan;115(1):e44–51.

Vintzileos AM, Ananth CV, Smulian JC, Scorza WE, Knuppel RA. Prenatal care and black-white fetal death disparity in the United States: heterogeneity by high-risk conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Mar;99(3):483–9.

Demissie K, Rhoads GG, Ananth CV, Alexander GR, Kramer MS, Kogan MD, et al. Trends in preterm birth and neonatal mortality among blacks and whites in the United States from 1989 to 1997. Am J Epidemiol. 2001 Aug 15;154(4):307–15.

Lane SD, Cibula DA, Milano LP, Shaw M, Bourgeois B, Schweitzer F, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in infant mortality: risk in social context. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2001 May;7(3):30–46.

Zuvekas A, Wells BL, Lefkowitz B. Mexican American infant mortality rate: implications for public policy. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2000 May;11(2):243–57.

Alexander GR, Tompkins ME, Allen MC, Hulsey TC. Trends and racial differences in birth weight and related survival. Matern Child Health J 1999 Jun;3(2):71–9.)

Partin MR. Explaining race differences in infant mortality in the United States (microform). PhD Thesis, University Microfilms International, 1993. Ann Arbor, 323p.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Compressed Mortality Files 1968–2015 on CDC WONDER Online Database, latest release December 2016. Data are from the Compressed Mortality Files as compiled from data provided by the 57 U.S. vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/on Nov 17, 2017 5:47:16 PM.

Goldstein RD, Kinney HC. Race, ethnicity and SIDS. Pediatrics. 2017;139:e20170898. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0898.

Holmes L, Charvan P, Blake T, Dabney K. Unequal cumulative incidence and mortality outcome in childhood brain and central nervous system malignancy in the United States. JRHED. 2018; https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-018-0462-5.

Moon RY. Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. SIDS and other sleep related deaths: evidence base for 2016 updated recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics 2016; 138(5) e20162940.

Altfeld S, Peacock N, Rowe LH, Massino J, et al. Moving beyond “abstinence-only” messaging to reduce sleep-related infant deaths. J Pediatr. 2017 Oct;189:207–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.06.069. Epub 2017 Aug 21

Colson ER, Geller NL, Heeren T, et al. Factors associated with choice of infant sleep position. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e2017596.

Ingram DD, Parker JD, Schenker N, Weed JA, et al. United States Census 2000 population with bridged race categories. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital health stat 2(135). 2003.

Arias E, Schauman WS, Eschbach K, Sorlie PD et al., The validity of race and Hispanic origin reporting on death certificates in the United States. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital health stat 2(148). 2008.

Pew Research Center. 2015. Multiracial in America: Proud, Diverse, and Growing in Numbers. Washington D.C.: June 2015.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mage, D.T., Maria Donner, E. & Holmes, L. Risk Differences in Disease-Specific Infant Mortality Between Black and White US Children, 1968–2015: an Epidemiologic Investigation. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 6, 86–93 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-018-0502-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-018-0502-1