Abstract

Objectives

The objectives of the study were to examine knowledge and perceptions of undergraduate and graduate students regarding participation in clinical trials and explore the degree to which knowledge and perceptions about research participation can vary by race.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was administered to undergraduate and graduate students between 18 and 35 years of age at a public minority-serving institution and a private, predominately-white university in the Southern United States. A total of 171 African American students and 119 Caucasian students completed the survey.

Results

Descriptive analyses were conducted and T- and chi-square tests were used to assess racial differences across key indicators. Fifty-nine percent of respondents were African American and 41 % were male. African American and Caucasian participants had similar experiences with research participation and had comparable knowledge about research participation. Racial differences were found in two areas. African American students with no prior research experience were more willing to participate in a future clinical trial (33 vs 22 %, p < 0.0001) and had a higher average perception of clinical research score (29.7 vs 27.4 %, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

The results from this study suggest that the gap between African American and Caucasian knowledge and perceptions about research may be closing and additional studies are needed to explore how generational differences can impact these factors among underrepresented groups. A deeper understanding of key influences associated with knowledge and perceptions among hard-to-reach populations would go a long way toward the development of culturally relevant and respectful clinical trial education programs that would inform potential participants before recruitment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Scientific discovery leading to the development of pharmaceutical products and innovative treatment regimens have made a number of infectious and chronic diseases imminently treatable over the past century [1]. However, these advancements have not translated into a major reduction in morbidity and mortality disparities between African and Caucasian Americans. The persistence of health disparities has been linked, in part, to historic underrepresentation of minorities participating in clinical trials [1–4]. These low clinical trial participation rates have often been attributed to factors such as limited awareness of clinical trials, low numbers of minority investigators, and a general distrust of scientists and the scientific enterprise [1, 4–9]. Previous studies have found that each of these factors are linked to lower clinical trial participation among African Americans; however, many of these studies have been limited by small sample sizes, a focus on attitudes pertaining to a particular disease, and study populations containing only racial/ethnic minorities [5, 6, 10, 11]. Despite these barriers, a recent report indicates improvement in participation rates of African American adults in National Institutes of Health (NIH) sponsored clinical trials [11]. Further, data from industry trials suggests that African Americans may be overrepresented in Phase I (safety studies designed to establish medication dosage and to determine adverse event) [11]. Paradoxically, African Americans are to be underrepresented among participants in Phase III therapeutic trials to establish efficacy and safety.

Researchers contend that considerable disparities in research participation between African Americans and Caucasians remain [1, 7]; however, there are signs that perceptions about research among African Americans and other minorities may be changing. Recent studies have shown that African Americans are interested in clinical trial participation [12] and have participation rates similar to Caucasians when recruited assertively [13]. These findings emphasize a need for investigators to consider the diversity of awareness, attitudes, and perceptions within minority groups about research and clinical trial participation [14]. It has been noted that older African Americans may be skeptical about research participation; however, it is not clear if younger African Americans, especially those who attend college, are equally suspicious of clinical studies. The number of African Americans attending predominately Caucasian research institutions has grown considerably over the past few decades, and an increasing number of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) have integrated funded research into their respective missions and operations during this same period. African Americans in undergraduate and graduate programs are more likely than earlier generations of minority students to have exposure to research studies and take multiple courses in which the research process and the responsible conduct of research are discussed. These undergraduate and graduate students are likely to be recruited for future clinical trials; therefore, an assessment of their knowledge and perceptions about research is important [2]. Few studies have examined knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of clinical trials among young African American adults in undergraduate and graduate programs [2], and no studies to our knowledge have explored the degree to which they differ from Caucasian college and graduate students. The primary objective of this study was to examine knowledge and perceptions about clinical trial participation among African American and Caucasian college and graduate students and explore the degree to which these factors vary by race.

Methods

Setting and Sample

The participants were undergraduate and graduate students between 18 and 35 years of age at a public minority-serving institution and a private, predominately-white university in the Southern USA. African Americans in the study were students at the minority-serving institution and Caucasian students were enrolled at the majority-serving institution. A very small number of students in this study attended institutions in which they were part of the minority population and they were omitted from the analysis. Professors, at both institutions, teaching undergraduate and graduate courses during the spring 2012 semester consented to permit students enrolled in their courses to be recruited and complete a one time, anonymous survey at the end of a predetermined class period. Students were assured that participation was anonymous and strictly voluntary. No students refused to participate. Institutional Review Boards at both institutions approved this study.

Survey Instrument

The questionnaire used in this study was comprised of measures used in earlier published studies specifying factors associated with minority participation in research [3, 15] and participant trust in medical research [16]. The survey instrument consisted of 75 items divided into eight sections addressing the following: (1) knowledge of clinical research (7 items), (2) perceptions of clinical research (8 items), (3) perceived advantages of participation (9 items), (4) perceived disadvantages of clinical research (7 items), (5) current and past participation in clinical trials (6 items), (6) trust in medical researchers (12 items), (7) hypothetical research-related scenarios (18 items), and (8) demographic characteristics (8 items). Questions in sections 1 though 5 were used in recent studies conducted by Kennedy and Burnett [3, 15] and the items in section 6 were developed by Hall and colleagues [16]. The questions in section 7 were administered as part of a larger study to measure respondents’ perceptions about and willingness to participate in obesity studies. Demographic information was collected in Section 8. The complete survey included 75 items, and the average completion time was approximately 25 min.

The primary measures of interest for this study were knowledge (section 1) and perceptions (section 2) of clinical research. The seven items used to assess knowledge of clinical research and eight items used to elicit perceptions of clinical research are presented in Table 1.

Participants were asked to respond to the knowledge and perceptions items using a five-point Likert scale, with responses that ranged from “strongly disagree” (coded 1) to “strongly agree” (coded 5). Respondents who were unsure could choose the “unsure” response (coded 3). Responses to the knowledge and perceptions items were summed for an overall score. The internal consistency reliability estimates for the knowledge (α = 0.88) and perception (α = 0.85) scale were consistent with the values found in earlier research [15]. The remaining variables in the analysis were demographic variables including gender, age, race, enrollment classification (i. e., freshmen, sophomore, etc.), marital status, and health status.

Analysis

Study population characteristics were described overall by race using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. T- and chi-square tests were used in descriptive analyses assessing racial differences across key indicators. Data were analyzed using StataSE version 12.

Results

Two hundred ninety (N = 290) individuals completed surveys. Most of the sample members were undergraduate students (96.8 %). A majority (59 %) of the respondents were African American. Approximately 41 % of sample was male and nearly 94 % of individuals in the study were between 18 and 25 years of age. An overwhelming majority of students (96 %) had never been married and a substantial majority (70.6 %) of individuals in the sample ranked their health status as “excellent” or “very good.” Nearly 23 % of respondents had been previously asked to participate in a clinical trial, and 13.2 % of the sample had actually participated in a clinical trial. Approximately 29 % of individuals in the study who had never been asked or had never previously participated in a clinical trial indicated that they were willing to participate in the future. The overall average score on the knowledge measure was 27.6 (SD = 5.3), and mean score for the perceptions of clinical research measure was 28.8 (SD = 5.5). .

The results in Table 2 highlight that the profile of African American students was distinct from their Caucasian counterparts. The distribution of students across classification and age categories were found to vary by race. Nearly 7 % of the Caucasian students were graduate students and all of the Caucasian students were younger than 25 years of age. In contrast, almost none of the African American students in the study were graduate students and 11 % percent of this group was over 25 years of age. An overwhelming majority of Caucasian students (85 %) were found to rate their health as “excellent” or “very good” while only 61 % of African American students rated their health in a similar manner.

The results associated with clinical trial participation indicate that African American and Caucasian students had similar experiences. The proportion of students who were asked to participate in a clinical trial or actually participated in a clinical trial did not vary across racial groups. The findings also indicated that African American and Caucasian students were similar in their knowledge about clinical research. According to Table 2, the difference in mean knowledge of clinical research scores between African American and Caucasian students was only 0.3, a statistically non-significant difference.

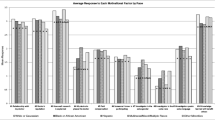

The results in Table 2 suggested that African American and Caucasian students were distinct in two areas associated with clinical participation. Among college and graduate students who had no experience with research participation, African Americans were more willing than their Caucasian counterparts to participate in a future clinical trial. Approximately one third (33.3 %) of African American participants who had never been recruited or never participated in a clinical trial responded affirmatively to an opportunity to take part in a future clinical trial while only 22.5 % of the corresponding Caucasian sample stated a willingness to participate in a future clinical trial. The results in Table 2 also show that African American students had a higher average perception of clinical research score (M = 29.7, SD = 5.0) than Caucasians in the study (M = 27.4, SD = 5.9). An analysis of individual item response patterns, presented in Table 3, indicated that African American study participants were more likely to “agree” or “strongly agree” with the statements asserting the benefits of clinical research than Caucasians on all but one item. The group differences were statistically significant for four of the eight perceptions of clinical research items.

Discussion

For decades, scientists have suggested that African American skepticism about research can be linked to lower levels of awareness and/or knowledge about research studies and conduct of responsible research [5–7]. Recent studies indicate that African Americans continue to be suspicious about research; however, it is not clear if the factors associated with their suspicions are the same. Furthermore, the current line of research does not provide any indication about the strength of the legacy of mistrust or prospects for change. Most of the extant research examining attitudes and perceptions about clinical trial participation focuses on middle age or older adults who were alive while studies like the United States Public Health Service study at Tuskegee were still active. Younger adults, especially college and graduate students, may have different experiences with and exposures to research. Few studies have examined knowledge and perceptions about research among African American college students [2], and no studies to our knowledge have compared their results with Caucasian students.

The results from our study suggest that the gap between African American and Caucasian knowledge and perceptions about research may be closing. Table 2 indicates that the knowledge of clinical research among African American students is equivalent to Caucasian students in the study. These findings suggest that research may have become a larger part of the African American college experience. The research enterprise has expanded to campuses with larger minority populations and African American students have more opportunities to learn about the scientific method and the responsible conduct of research through coursework and opportunities to participate in and on research studies. It may be the case that these experiences have contributed to negligible gaps in knowledge and awareness about the research enterprise; however, additional studies are needed to examine how the presence of active research projects at minority-serving institutions have implications for alumni research participation in the short and long term.

The results associated with research perceptions are encouraging. According to Table 2, African American students have higher research perception scores than their Caucasian peers. A closer inspection of the individual items indicate that a larger segment of African American students strongly agree with statements such as “blood work is necessary in a clinical trial,” “participation in a clinical trial can delay a disease,” and “participation in a clinical trial can prevent a disease.” Furthermore, African American students were also more likely than their Caucasian counterparts to perceive that participation in clinical trials could help them and their families and help future generations. These results indicate that African American students in this study had positive perceptions of clinical research which is a significant shift from prevailing notions about research participation among African Americans.

This study presents findings that encourage researchers to consider others factors impacting knowledge and perceptions about research among African Americans. There are some limitations worth noting however. The survey items focused on clinical research in general and did not ask participants to consider research focusing on specific diseases. As such, it was not possible to consider how perceptions about clinical research could vary by type of clinical research. It is also noteworthy that the study population contained a small proportion of graduate students. An analysis of data without these students was performed, and the results were similar to those reported in Tables 2 and 3. The modest sample size does not provide enough power for the use of inferential statistics that could examine the relationship between knowledge and perceptions about research participation. It is also important to note that the results are derived from data drawn from students attending two post-secondary institutions in the South; therefore, the results are not generalizable to all African American or Caucasian college-age individuals. Additionally, all of the African American students attended an HBCU and all of the Caucasian students were enrolled at a majority-serving institution. Consequently, the type of institution may be a confounding variable for racial status. Furthermore, all of the usual limitations of cross-sectional and self-report studies apply [17].

African Americans and other minorities are attending college in greater numbers and our results suggest that this demographic shift can improve prospects for minority clinical trial participation. Further studies are needed to specify factors associated with favorable perceptions about clinical trial participation among racial and ethnic minority group members attending college and graduate school. Clinical trial participation rates are relatively low among the general population regardless of race or ethnicity; however, our results indicate that college and graduate school students of color have an appreciation of the importance of clinical trial participation and express a willingness to participate. Positive perceptions about clinical research are not equivalent with actual participation; however, these perceptions are indicative of the potential for an increase in participation rates. Our findings encourage investigators to consider that generational differences and exposure to scientific research can influence knowledge and perceptions about research and clinical trial participation among underrepresented groups.

References

Powell JH, Fleming Y, Walker-McGill CL, Lenoir M. The project IMPACT experience to date: increasing minority participation and awareness of clinical trials. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(2):178–87.

Diaz VA, Mainous 3rd AG, McCall AA, Geesey ME. Factors affecting research participation in African American college students. Fam Med. 2008;40(1):46–51.

Kennedy BM, Burnett MF. Clinical research trials: factors that influence and hinder participation. J Cult Divers. 2007;14(3):141–7.

George S, Duran N, Norris K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):e16–31. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301706.

Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St George DM. Distrust, race, and research. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(21):2458–63.

Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(9):537–46.

Durant RW, Legedza AT, Marcantonio ER, Freeman MB, Landon BE. Different types of distrust in clinical research among whites and African Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(2):123–30.

Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Racial differences in factors that influence the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12(4):248–56.

Shavers-Hornaday VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF, Torner JC. Why are African Americans under-represented in medical research studies? Impediments to participation. Ethn Health. 1997;2(1–2):31–45. doi:10.1080/13557858.1997.9961813.

Braunstein JB, Sherber NS, Schulman SP, Ding EL, Powe NR. Race, medical researcher distrust, perceived harm, and willingness to participate in cardiovascular prevention trials. Medicine. 2008;87(1):1–9. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e3181625d78.

Fisher JA, Kalbaugh CA. Challenging assumptions about minority participation in US clinical research. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(12):2217–22. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300279.

Cottler LB, MCCloskey DJ, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Bennett NM, Strelnick H, Dwyer-White M et al. Community needs, concerns, and perceptions about health research: findings from the Clinical and Translational Science Award Sentinel Network. American Journal of Public Health. 2013:e1-e8. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300941.

Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, Van Wye G, Christ-Schmidt H, Pratt LA, et al. Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Med. 2006;3(2):e19. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030019.

BeLue R, Taylor-Richardson KD, Lin J, Rivera AT, Grandison D. African Americans and participation in clinical trials: differences in beliefs and attitudes by gender. Contemporary clinical trials. 2006;27(6):498–505. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2006.08.001.

Kennedy BM, Burnett MF. Clinical research trials: a comparison of African Americans who have and have not participated. J Cult Divers. 2002;9(4):95–101.

Hall MA, Camacho F, Lawlor JS, Depuy V, Sugarman J, Weinfurt K. Measuring trust in medical researchers. Med Care. 2006;44(11):1048–53. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000228023.37087.cb.

Bruce MA, Sims M, Miller S, Elliott V, Ladipo M. One size fits all? Race, gender and body mass index among U.S. adults. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(10):1152–8.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health (Prime Award Number 1 CPIMP091054-04) the to University of Mississippi Medical Center’s Institute for Improvement of Minority Health and Health Disparities in the Delta Region and career development awards from NHLBI to Jackson State University (1 K01 HL88735-05—Bruce). The authors thank Ms. Lovie Robinson, Dr. Gerrie Cannon Smith, Dr. London Thompson, Ms. Ashley Wicks, Rev. Thaddeus Williams, and Mr. Willie Wright for their support of this study.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Bruce, Dr. Beech, Ms. Hamilton, Ms. Collins, Ms. Harris, Mr. Wentworth, and Ms. Crump have no financial relationships with the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health (Prime Award Number 1 CPIMP091054-04) or the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1 K01 HL88735-05) and declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all participants for being included in the study.

Animal Studies

No animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bruce, M.A., Beech, B.M., Hamilton, G.E. et al. Knowledge and Perceptions about Clinical Trial Participation among African American and Caucasian College Students. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 1, 337–342 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-014-0041-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-014-0041-3