Abstract

Purpose

Racial/ethnic disparities in the level of physical activity may be due to unequal opportunities to be physically active. This study compares the attributes of physical activity resources for adolescents by neighborhood race/ethnicity in a metropolitan area in southern USA.

Methods

Physical activity resources (n = 89) were assessed using the revised Physical Activity Resource Assessment instrument. Neighborhood ethnic composition for each resource was identified from the US census data.

Results

On average, resources in high ethnic minority neighborhoods had more (p = 0.032) physical activity features (mean = 3.24, SD = 1.6) compared to low ethnic minority neighborhoods (mean = 2.36, SD = 1.7). However, the quality of amenities in high ethnic minority neighborhoods was significantly low (p = 0.037). The incivilities that indicated safety concerns (i.e., unattended dogs, evidence of alcohol and substance use, graffiti, sex paraphernalia, and vandalism) were significantly higher (p = 0.009) in the resources in high ethnic minority neighborhoods (mean = 1.07, SD = 1.6) compared to resources in low ethnic minority neighborhoods (mean = 0.36, SD = 0.8).

Conclusions

Physical activity resources in high minority neighborhoods were found to have significant quality and safety issues. Further studies are warranted to examine the use of these resources by adolescents and examine its association with physical activity levels and obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is a major public health concern in the USA. More than one third of US adolescents (33.6 %) are either overweight or obese [1]. Further, obese adolescents are more likely to be obese as adults and are at higher risk for chronic diseases [2–4]. While all youth are at risk, rates of obesity are disproportionately high among minority populations with 41.2 % non-Hispanic black and 42.4 % Hispanic adolescents being overweight or obese compared to 30 % non-Hispanic white youth [1]. Lack of physical activity is one of the modifiable health risk behaviors related to obesity. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans issued by the US Department of Health and Human Services recommends that children and adolescents should engage in 60 min or more of moderate to vigorous physical activity every day [5]. However, in 2011, less than one third of high school students met these recommendations [6]. Like obesity, there are disparities in levels of physical activity by race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and geographic region. Black and Hispanic youth are less likely to engage in physical activity compared to their white counterparts [6]. Moreover, children and adolescents residing in the south have lower levels of physical activity than other regions of the USA. [6, 7].

Past studies have indicated several reasons for low levels of physical activity among children and adolescents, including the influence of the built environment. The physical features of built environment including parks, playgrounds, and other recreational resources provide opportunities for structured exercise and physical activity [8, 9]. Prior research has found that children with access to parks and recreation facilities are more active than children without access to these physical activity resources [10–12]. Open public spaces, publicly available recreational facilities, and transportation are positively associated with children's participation in physical activity [13].

Disparities in the level of physical activity may be due to unequal opportunities to be physically active. For example, neighborhoods with low socioeconomic status have been found to have fewer physical activity resources [14]. Moore et al. [15] examined the distribution of parks and recreational facilities in three geographic locations (North Carolina, New York, and Maryland) in the USA. They found that low-income minority neighborhoods were less likely to have public recreational facilities than white neighborhoods [15]. Similarly, Powell and colleagues, using the national data, found that commercial physical-activity-related facilities were less likely to be present in low-income and high ethnic minority neighborhoods [16]. The attributes (such as features and amenities) are important factors that may positively or negatively influence the use of a physical activity resource. A resource may be easily accessible, but if it does not offer any features or equipment to encourage physical activity, it is less likely to be visited [17, 18]. Parks with adequate features (e.g., basketball court and tennis court) and amenities (e.g., lighting, shelter, and drinking fountain) are more likely to attract and engage children in physical activities [11, 19–21]. On the other hand, a resource that is perceived to be unsafe or is unclean is less likely to be used [22]. However, very few studies have examined disparities by these attributes of physical activity resources [23–25], and none have examined the quality of parks and recreational resources in the deep south area of the USA. The purpose of this study was to compare the attributes of physical activity resources by neighborhood race/ethnicity in a metropolitan area in southern USA.

Methods

Setting

This study was conducted in metropolitan Birmingham, AL. Data from the 2011 national Youth Risk Behavior Survey indicated that 17.3 % of high school students in Alabama did not participate in at least 60 min of physical activity on any day during the 7 days prior to the survey [26]. Further, among Alabama's youth enrolled in grades 9 through 12, 17 % were obese compared to the national average of 13 % in 2011 [26].

Data for this study were collected as part of a larger project looking at factors influencing physical activity among African American adolescents in Birmingham, AL [27, 28]. The larger project included self-reported assessments of sociocultural influences on physical activity by African American adolescents (age 12–16 years) and their parents, as well as assessments of participants' built environment for physical activity. Findings from the self-reported data are published elsewhere [27]. This study uses data from the objective assessment of the built environment. Physical activity resources located within a 1-mi radius of the homes of participants of the larger study were identified and assessed. First, parks and recreational resources were identified using Internet searches and listings on local and state departments of parks and recreation. Then, an online global mapping program was used to identify additional resources and map the location. Whenever possible, the location and hours of operation of resources were confirmed by phone. Finally, research staff conducting field assessments was asked to identify during their travels throughout the community any resource that had not been identified by initial searches. The purpose of the study was to assess physical activity resources available to the public without any restriction or affiliation. Therefore, private facilities and resources located on school property or churches were excluded.

Assessments were conducted independently by trained research staff (graduate level students) during daylight hours. Training of the staff included didactic instruction on the instrument and assessment protocol and a field test of a local physical activity resource. Prior to conducting independent assessments, raters had to demonstrate 100 % agreement with the trainer's assessment of another field test site. During the time frame of independent assessments, raters received ongoing supervision from the trainer to address any questions/problems in conducting the assessments or scoring the measures. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University.

Physical Activity Resource Measure

Trained research staff assessed each physical activity resource using the revised Physical Activity Resource Assessment (PARA) instrument [24]. The PARA instrument has demonstrated good reliability (kappa > 0.77) and has been tested in low-income and high ethnic minority concentration neighborhoods in previous studies [24, 29, 30]. The assessment included the type of resource, size, cost for use, and hours of operation. Each resource was assessed on number, type, and quality of features and amenities it possessed, and the overall incivilities. The instrument included a list of 13 features used specifically for physical activity (e.g., basketball courts, exercise stations, and tennis courts) and 12 amenities (e.g., bathrooms, shower, and benches). Features and amenities were rated for quality as “3 = good”, “2 = fair”, and “1 = poor”. Physical activity resources were also assessed for incivilities (e.g., auditory annoyance, dog refuse, graffiti, and vandalism). In addition to the 12 incivilities in the original instrument, we added “ground erosion” as earlier observations of physical activity resources in the study area included multiple areas that appeared to be impacted by poor drainage and other circumstances leading to visible erosion of the land. Incivilities were rated as “0 = none”, “1 = little”, “2 = medium”, and “3 = a lot”. We included three additional items for a subjective assessment of the physical activity resource. Additional items included the overall safety (“This resource is safe”), aesthetics (“This resource is aesthetically pleasing”), and activity-friendly environment (“This resource has enough equipment and/or activities to keep a teen active”). Response included “0 = strongly disagree” to “3 = strongly agree”. The assessors were also asked to include comments on the instrument to justify their subjective assessment.

Census Data

The neighborhood ethnic composition for each physical activity resource was compiled from the 2010 US census data [31]. American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year estimates were used to retrieve census tract data. Census tracts are small, relatively permanent geographic areas with populations of 2,500–8,000 residents and boundaries that follow visible features [32]. Socioeconomic characteristics including median household income, percent below poverty line, and percent female-headed household were also obtained.

Analysis

A predominantly minority neighborhood is defined as a geographical area in which 50 % or more of the persons residing therein are minorities based upon the most recent census data [33]. We used a more conservative approach to classify physical activity resources as belonging to high (>70 % ethnic minority) versus low ethnic minority neighborhood (<40 % ethnic minority). We used this approach to eliminate any bias in racially mixed neighborhoods with about an equal proportion of white and minority population. Resources that did not meet these criteria were initially analyzed as a third category (racially mixed). However, these were not statistically different from resources in high or low minority neighborhoods so they were removed from the analyses. Socioeconomic characteristics of resources in high versus low minority neighborhoods were compared using t test. Then, these resources were compared on features, amenities, and incivilities. Finally, chi-square test was used to compare the resources in high versus low minority neighborhoods on the overall subjective assessment (safety, aesthetics, and activity-friendly environment). Data were analyzed using SPSS version 20.

Results

A total of 111 physical activity resources were assessed. The final analyses for this study included 67 resources belonging to high ethnic minority neighborhoods and 22 resources belonging to low ethnic minority neighborhoods. The majority of the resources assessed were public parks (72 %) and about 19 % were community centers. The rest were either a sport facility or a combination of park and community center. The size of resources varied from small, i.e., ½ square block (38 %) to large, i.e., >1 square block (36 %). Most resources were freely accessible at no cost (85 %); others required fee for certain programs such as the use of the swimming pool or tennis court.

Table 1 describes the characteristics of neighborhoods where the physical activity resources were assessed. High ethnic minority neighborhoods had predominantly African American population (90 %) and about 1.2 % of the population belonging to other minority groups. Whereas only 11.3 % African Americans and 3.6 % other minority groups resided in low ethnic minority neighborhoods. The high ethnic minority neighborhoods had significantly lower median household income ($28,600 vs $64,363), higher percentage of people below poverty level (30.5 % vs 8.9 %), and higher percentage of female-headed households (31.5 % vs 9.7 %) compared to the low minority neighborhoods.

The physical activity resources were assessed for 13 possible features and 12 possible amenities (Table 2). The resources in high ethnic minority neighborhoods, on average, had more (p = 0.032) physical activity features (Mean = 3.24, SD = 1.6) compared to low ethnic minority neighborhoods (Mean = 2.36, SD = 1.7). The most commonly observed features overall were play equipment and sidewalks (64 % each). Resources in high ethnic minority neighborhoods had basketball courts (61 %) and baseball fields (39 %), and those in low ethnic minority neighborhoods had trails (27 %) and soccer fields (23 %). There was no significant difference in the quality of the available features. On average, the assessed resources had about half of the possible 12 amenities, both in high (Mean = 6.46, SD = 2.1) and low (Mean = 6.18, SD = 2.4) ethnic minority neighborhoods. The most common amenities in the assessed resources were trash bins, benches, lights, shelter, picnic tables, and drinking fountains. However, the quality of amenities in high ethnic minority neighborhoods was significantly lower than in low ethnic minority neighborhoods (p = 0.037). The total incivilities in resources belonging to high ethnic minority neighborhoods was high (Mean = 5.70, SD = 4.2) compared to the low ethnic minority neighborhoods (Mean = 4.14, SD = 3.9), although this difference was not statistically significant. When analyzed separately, the incivilities that indicated a safety concern (i.e., unattended dogs, evidence of alcohol and substance use, graffiti, sex paraphernalia, and vandalism) were significantly higher (p = 0.009) in the resources in high ethnic minority neighborhoods (Mean = 1.07, SD = 1.6) compared to the resources in low ethnic minority neighborhoods (Mean = 0.36, SD = 0.8). About 45 % of the resources in the high ethnic minority neighborhoods had one or more incivilities that indicated a safety concern compared to 18 % of resources in low ethnic minority neighborhoods. Alcohol use (30 %), graffiti (25 %), and vandalism (16 %) were the common safety issues found in the resources in high minority neighborhoods.

The overall subjective assessment by the assessors indicated that only about 41 % of the assessed resources were perceived to have enough equipment for a teen to be physically active. About 90 % of the resources were considered to be safe. Most resources (67 % in high ethnic minority and 77 % in low ethnic minority neighborhoods) were perceived to be aesthetically pleasing. Resources in high ethnic minority neighborhoods scored lower in safety and aesthetics than the resources in low ethnic minority neighborhoods, although this difference was not statistically significant.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the attributes of publicly available physical activity resources in an urban city in southern USA with high rates of overweight and obesity. Comparing the resources in high versus low ethnic minority neighborhoods, we found some significant differences. The resources in high ethnic minority neighborhoods, on average, had more physical activity features compared to low ethnic minority neighborhoods. However, the quality of amenities in high ethnic minority neighborhoods was significantly low. The incivilities that indicated safety concerns were significantly higher in the resources in high ethnic minority neighborhoods compared to the resources in low ethnic minority neighborhoods.

Past studies have noted the lack of availability of physical activity resources among low-income and minority groups [14, 15, 34]. However, when examined for attributes within the available resources, the current study found that resources within low-income and minority neighborhoods had a comparable number of features and amenities. This finding is consistent with two other studies conducted in the USA that examined the attributes of physical activity resources. Lee and colleagues found that physical activity resources in Kansas City across low and high ethnic minority neighborhoods were similar in number, features, and amenities [24]. Another study conducted by Vaughan and colleagues found that the number of resources, features, and amenities per park was not significantly different across income or percent minority census tracts [25]. In the current study, we found that the distribution of specific park features was appropriate with the preference of activity in the target population, i.e., more basketball courts in high minority and more soccer fields in low minority neighborhoods. Overall, the resources had at least two to three features. However, in the subjective assessment, the assessors perceived the lack of enough equipment for teens in more than half of the resources. The most commonly observed features were play equipment and sidewalks that may not attract teens for physical activity. The assessors noted comments to justify the reason for their perceptions. Some comments were “This could be a place for teens if they have their own equipment” and “Park is geared towards younger children or older adults for walking. Not much for a teen to do here other than use the track or sit at a table/bench”. Even when one or two features were present, the assessors noted that it may not be sufficient, especially if that activity or sport is not preferred by the teen. “Other than the [basketball] court there is nothing here for teens to do, there isn’t even enough flat space without trees to play another sport.” These findings indicate the need for more age-appropriate features in the resources in the examined neighborhoods.

Resources belonging to high minority neighborhoods rated low on the quality of features and amenities and had higher number of incivilities, a finding similar to the past studies [24, 25]. The relative score of incivilities observed was low (average of 5), although incivilities that indicated safety concerns showed statistically significant differences between high and low minority neighborhoods. On average, high minority neighborhoods showed greater evidence of alcohol use, vandalism, etc. In subjective assessment by the study staff, about 90 % of the resources were perceived to be safe; however, perception by the assessors might be different from teenagers and others who have greater familiarity with the resources. For example, assessors were more often unfamiliar with the areas assessed and spent, on average, less than 30 min at each resource typically during the middle of a weekday. As such, staff commented that “so as long as nothing happened while I was there and the park was well-kept overall, I assessed it as safe.” Therefore, someone who lives near the resource may be more aware of a neighborhood's history and may feel more or less safe while visiting a park in that area.

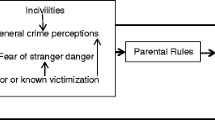

Safety is a commonly reported obstacle to physical activity in low-income minority neighborhoods [35]. Low perceived safety is negatively associated with walking to and from school [36]. Parents often restrict their children indoor, if they perceive their neighborhoods to be unsafe [37, 38]. In a qualitative research study with African Americans, high school students reported that they would avoid physical activity resources where people are engaged in drug or gang activities [39]. Concerns about safety largely determine the use of a resource, especially for adolescent girls [39]. Low-income neighborhoods often lack safety attributes that can facilitate physical activity for recreational purposes [40].

The assessment of physical activity resources in this southern US metropolitan area indicates that there were no differences in the attributes, especially physical activity features, belonging to high versus low minority neighborhoods. The safety concerns noted in our assessments may be due to the lack of supervision and/or maintenance of those resources, which may have attracted inappropriate activities. However, it might be a vicious cycle. Concerns of the safety and poor quality of resources may discourage the use of a resource, and a less frequently visited resource may attract more malicious behavior and is less likely to be maintained by concerned authorities. Community efforts such as park events, organized classes, cleanups, and neighborhood watch programs may help increase the visitation of physical activity resources and reduce inappropriate activities in these resources [8]. In a study in southern California, the number of staff and supervised and organized programs were strongly correlated with park use [41]. Further, children and adolescents are likely to use resources where they perceive the presence of safe adults [42]. Therefore, resources that offer a mix of opportunities for teens and adults may attract more people and create a safe physical environment for adolescents.

There are certain limitations of this study that warrant consideration. First, we examined only publicly accessible resources. Resources belonging to schools, churches, or commercial facilities were not examined. It is possible that there are disparities in the number and quality of these private resources in high versus low minority neighborhoods. Second, we did not examine transportation, crime, and safety issues outside of the assessed resources. The proximity, better traffic safety, and opportunity to walk or bike is associated with the use of physical activity among adolescents [43]. Nevertheless, the findings of this study indicate an important disparity in the quality and safety of physical activity resources in high ethnic minority neighborhoods. In addition, resources were audited during times (mostly weekdays, business hours) in which adolescents were not around. The focus of this study was on what physical resources were available and, thus, maximizing opportunities to assess sites during times that teens would be present was not a priority. Future work should focus on assessing the link between resource availability and usage among teens. Finally, while the revised PARA instrument used in the study provided opportunity to subjectively assess teen-specific attributes of physical activity resources, teen-specific objective measurement tools may be warranted.

Conclusion

Features, amenities, aesthetics, and safety are all important factors affecting the use of a physical activity resource [17]. Parks with more features and amenities are more likely to be visited and used for physical activity [18, 19]. Low-cost resources that offer preferred activities are more likely to attract adolescents [37]. Nonetheless, a resource that is not well maintained or is perceived to be unsafe may discourage its use. In the current study, the examined resources were comparable in the number of features and amenities. However, quality and safety issues were significant in the resources belonging to high ethnic minority neighborhoods. Further studies are warranted to examine the use of these physical activity resources in high minority neighborhoods by adolescents and examine its association with physical activity and obesity.

References

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):483–90.

Freedman DS, Mei Z, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS, Dietz WH. Cardiovascular risk factors and excess adiposity among overweight children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Pediatr. 2007;150(1):12–17 e2.

Li C, Ford ES, Zhao G, Mokdad AH. Prevalence of pre-diabetes and its association with clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors and hyperinsulinemia among U.S. adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(2):342–7.

Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. The relation of childhood BMI to adult adiposity: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1):22–7.

USDHHS: Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans Midcourse Report: strategies to increase physical activity among youth. 2012. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans Midcourse Report Subcommittee of the President's Council on Fitness Sports & Nutrition. http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/midcourse/

Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2011. MMWR. 2012. 61(4).

Springer AE, Hoelscher DM, Kelder SH. Prevalence of physical activity and sedentary behaviors in US high school students by metropolitan status and geographic region. J Phys Act Health. 2006;3:365.

Blanck HM, Allen D, Bashir Z, Gordon N, Goodman A, Merriam D, et al. Let’s go to the park today: the role of parks in obesity prevention and improving the public’s health. Child Obes. 2012;8(5):423–8.

Wolch J, Jerrett M, Reynolds K, McConnell R, Chang R, Dahmann N, et al. Childhood obesity and proximity to urban parks and recreational resources: a longitudinal cohort study. Health Place. 2011;17(1):207–14.

Ding D, Sallis JF, Kerr J, Lee S, Rosenberg DE. Neighborhood environment and physical activity among youth a review. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4):442–55.

Cohen DA, Ashwood JS, Scott MM, Overton A, Evenson KR, Staten LK, et al. Public parks and physical activity among adolescent girls. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):e1381–9.

Veugelers P, Sithole F, Zhang S, Muhajarine N. Neighborhood characteristics in relation to diet, physical activity and overweight of Canadian children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2008;3(3):152–9.

Davison KK, Lawson CT. Do attributes in the physical environment influence children’s physical activity? A review of the literature. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2006;3:19.

Estabrooks PA, Lee RE, Gyurcsik NC. Resources for physical activity participation: does availability and accessibility differ by neighborhood socioeconomic status? Ann Behav Med. 2003;25(2):100–4.

Moore LV, Diez Roux AV, Evenson KR, McGinn AP, Brines SJ. Availability of recreational resources in minority and low socioeconomic status areas. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(1):16–22.

Powell LM, Slater S, Chaloupka FJ, Harper D. Availability of physical activity-related facilities and neighborhood demographic and socioeconomic characteristics: a national study. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(9):1676–80.

McCormack GR, Rock M, Toohey AM, Hignell D. Characteristics of urban parks associated with park use and physical activity: a review of qualitative research. Health Place. 2010;16(4):712–26.

Tucker P, Gilliland J, Irwin JD. Splashpads, swings, and shade: parents’ preferences for neighbourhood parks. Can J Public Health. 2007;98(3):198–202.

Kaczynski AT, Potwarka LR, Saelens BE. Association of park size, distance, and features with physical activity in neighborhood parks. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(8):1451–6.

Giles-Corti B, Broomhall MH, Knuiman M, Collins C, Douglas K, Ng K, et al. Increasing walking: how important is distance to, attractiveness, and size of public open space? Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(2 Suppl 2):169–76.

Shores KA, West ST. The relationship between built park environments and physical activity in four park locations. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(3):e9–e16.

Gobster PH. Managing urban parks for a racially and ethnically diverse clientele. Leis Sci. 2002;24:143–59.

Crawford D, Timperio A, Giles-Corti B, Ball K, Hume C, Roberts R, et al. Do features of public open spaces vary according to neighbourhood socio-economic status? Health Place. 2008;14(4):889–93.

Lee RE, Booth KM, Reese-Smith JY, Regan G, Howard HH. The Physical Activity Resource Assessment (PARA) instrument: evaluating features, amenities and incivilities of physical activity resources in urban neighborhoods. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2005;2:13.

Vaughan KB, Kaczynski AT, Wilhelm Stanis SA, Besenyi GM, Bergstrom R, Heinrich KM. Exploring the distribution of park availability, features, and quality across Kansas City, Missouri by income and race/ethnicity: an environmental justice investigation. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45 Suppl 1:S28–38.

YRBSS, Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance. 2011, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Division for Adolescent and School Health: Atlanta, GA.

Baskin ML, Thind H, Affuso O, Gary LC, LaGory M, Hwang SS. Predictors of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) in African American young adolescents. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45(Suppl 1):S142–150.

Dulin-Keita A, Kaur Thind H, Affuso O, Baskin ML. The associations of perceived neighborhood disorder and physical activity with obesity among African American adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:440

Heinrich KM, Lee RE, Regan GR, Reese-Smith JY, Howard HH, Haddock CK, et al. How does the built environment relate to body mass index and obesity prevalence among public housing residents? Am J Health Promot. 2008;22(3):187–94.

McAlexander KM, Banda JA, McAlexander JW, Lee RE. Physical activity resource attributes and obesity in low-income African Americans. J Urban Health. 2009;86(5):696–707.

US Census Bureau: American FactFinder. 2013. http://factfinder2.census.gov/.

United States Census Bureau: Census tracts and block numbering areas. 2013. United States Census Bureau.

Resolution Trust Corporation: Definition of predominantly minority neighborhood. 1994, Federal Register 12 CFR 1630. Retrieved from https://federalregister.gov/a/94-18063

Gordon-Larsen P, Nelson MC, Page P, Popkin BM. Inequality in the built environment underlies key health disparities in physical activity and obesity. Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):417–24.

Kumanyika S, Grier S. Targeting interventions for ethnic minority and low-income populations. Future Child. 2006;16(1):187–207.

Zhu X, Arch B, Lee C. Personal, social, and environmental correlates of walking to school behaviors: case study in Austin, Texas. Scientific World Journal. 2008;8:859–72.

Dias JJ, Whitaker RC. Black mothers’ perceptions about urban neighborhood safety and outdoor play for their preadolescent daughters. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(1):206–19.

Weir LA, Etelson D, Brand DA. Parents’ perceptions of neighborhood safety and children’s physical activity. Prev Med. 2006;43(3):212–7.

Ries AV, Gittelsohn J, Voorhees CC, Roche KM, Clifton KJ, Astone NM. The environment and urban adolescents’ use of recreational facilities for physical activity: a qualitative study. Am J Health Promot. 2008;23(1):43–50.

Sallis JF, Slymen DJ, Conway TL, Frank LD, Saelens BE, Cain K, et al. Income disparities in perceived neighborhood built and social environment attributes. Health Place. 2011;17(6):1274–83.

Cohen DA, Han B, Derose KP, Williamson S, Marsh T, Rudick J, et al. Neighborhood poverty, park use, and park-based physical activity in a Southern California city. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2317–25.

Romero AJ. Low-income neighborhood barriers and resources for adolescents’ physical activity. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36(3):253–9.

Grow HM, Saelens BE, Kerr J, Durant NH, Norman GJ, Sallis JF. Where are youth active? Roles of proximity, active transport, and built environment. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(12):2071–9.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Active Living Research (ALR)/Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) grant #65659 to Monica L. Baskin. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thind, H., Townsend, S., Godsey, E. et al. Physical Activity Resource Attributes by Neighborhood Race/Ethnicity in a Southern US City. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 1, 29–35 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-013-0004-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-013-0004-0