Abstract

This study describes the natural dictionary-using behaviors of a group of first-year English majors at Fudan University, Shanghai. It aims to gain some insights into how Chinese students as competent English learners actually use and view their dictionaries in the highly digitalized era, as well as the most common problems they encounter in finding contextual meanings for the looked-up words and the possible causes. The students were set a dictionary consultation assignment which was a near replication of Nesi and Haill’s (Int J Lexicogr 15(4):277–305, 2002) study of the dictionary-using habits of international students at a British university. Observations are made on what types of dictionaries and which dictionaries these Chinese students normally use, revealing a general tendency among the students to use multiple dictionaries in the digital medium. The outcomes of dictionary consultation are closely examined to map out the dictionary look-up patterns by the Chinese students and to identify various look-up problems. The findings demonstrate a preference of reading L1 translations over L2 definitions for the looked-up word, certain unrealistic expectations for L1 translations offered in the dictionaries, and the consequent difficulty experienced in identifying the dictionary sub-entry appropriate for the word’s contextual meaning. Also manifest is the growing confidence of a younger generation of dictionary users regarding the critical opinions they have formed of dictionaries despite a minimum exposure to dictionary teaching. These firsthand data on dictionary use under natural conditions will also be applied in the design of an introductory course on lexicography for undergraduates at the English department, Fudan University.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The use of dictionaries by language learners has always been the focus of many fruitful lexicographic studies. Through the efforts of researchers, much light has been shed upon the pros and cons of different types of dictionaries used in different learning activities and environments. In-depth studies and comparisons were made of bilingual, monolingual, and bilingualized dictionaries (BLDs) over the years (Béjoint 1981; Tono 1989; Hartmann 1994; Atkins 1996; Atkins and Varantola 1998; Cowie 1999; Laufer and Kimmel 1997; Lew 2004; Butzkamm 2009; Cook 2010; Zarei 2010; Chen 2011; Levine 2011; Augustyn 2013). Since about 20 years ago, more attention has been devoted to the comparison between dictionaries in print and in various digital media (Tang 1997; Nesi 1999; De Schryver 2003; Stirling 2003; Midlane 2005; Chen 2007, 2010; Kobayashi 2008; Dziemianko 2010, 2011, 2012). Though studies on dictionary use almost invariably set dictionary users as the ultimate beneficiary, it is only very lately that researchers seemed to start treating users as the starting point as well as the focal point of their studies. How users actually use their dictionaries was observed and described (De Schryver and Joffe 2004; De Schryver et al. 2006); direct user responses were elicited online (Müller-Spitzer et al. 2012); the new eye-tracking method was adopted to observe various user behaviors (Simonsen 2009, 2011; Kaneta 2011; Tono 2011; Lew et al. 2013; Müller-Spitzer et al. 2014); and the novel concepts of bottom-up editing and simultaneous feedback were finally given due and fair considerations (De Schryver 2000; Ding 2008).

In mainland China, most studies carried out among EFL learners still focus on the effects of different dictionaries in language comprehension, production, and vocabulary learning (Yu 1999; Kan and Wang 2003; Lang and Li 2003; Deng 2006; Zhang 2004; Chen 2007, 2010, 2011; Li 2009). Few efforts have been made in studying dictionary users in relation to the dictionaries they actually use. This study therefore sets upon itself the mission of obtaining and examining firsthand data on the dictionary-using behavior of first-year English majors at Fudan University in China. To be more specific, how this particular group of users use their dictionaries in vocabulary learning, the most common part of their daily study as English majors. The students were set a dictionary consultation assignment to report on the dictionaries they use in their everyday study and then the whole look-up process of eight new words in reading materials of their choice. This was a near replication of Nesi and Haill’s (2002) study of dictionary use by international students at a British university, which was intended to “monitor dictionary use under somewhat more natural conditions” (278). It is exactly how the Chinese students “naturally” use, choose, and evaluate their dictionaries that this study attempts to probe into and portray as realistically as possible.

2 Background and method of the study

Established in 1905, the English department at Fudan University is one of the oldest departments in this university in China. It was the very birthplace of the English-Chinese Dictionary (unabridged, 1st edition 1989, 2nd edition 2007), by far the most authoritative and popular bilingual dictionary in the Chinese-speaking world. Each year students who excel in the subject of English at high schools throughout the country still compete eagerly to be admitted into the Fudan English department. It seems, hence, quite a pity that no course on lexicography or dictionary use in general has ever been introduced here. Fortunately, a proposition by the current author to run a course of “Introduction to Lexicography” to undergraduates has been recently approved by the department. The purpose of this course is no other than to cultivate dictionary awareness among our English majors and to help them to better use their dictionaries. In other words, they will be instructed and encouraged to become more self-reflective as dictionary users, to explore fully the potentials of dictionaries in the digital era as a resourceful language learning companion, and to interact with this companion more effectively, efficiently, and with more satisfaction (Lew and De Schryver 2014: 344).

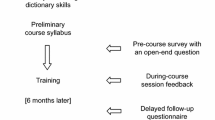

By inviting the first-year students to participate in a dictionary consultation assignment, this study aims to gain some insight into their habits as dictionary users after one semester’s study at the English department. As it is unfeasible to incorporate both decoding and encoding tasks into one consultation assignment, a decision was made to look into the students’ dictionary-using behaviors in decoding activities only in this study. For one thing, Nesi and Haill’s (2002) study on which this current one was modeled looked also into dictionary use by students in reading comprehension activities. What is more, the first-year English majors at Fudan are still expected to concentrate mainly on vocabulary building and text comprehension, both of which comprise primarily decoding tasks. And since the findings of this study will be used for the reference in designing the contents for the aforementioned dictionary course, it is reasonable to take into consideration what kinds of use the students are most likely to make of dictionaries at the current stage of their study.

The dictionary consultation task was issued as a winter-break assignment to 70 students in total on a voluntary basis. These students were first asked to name all the dictionaries they use for their study, and identify the most frequently used dictionary and reasons as well as occasions for using it. Then they were to record the entire look-up process of 8 new words in the reading text of their choice. At the end of the assignment, they were asked to describe their ideas of a good learners’ dictionary. The students were not asked to report how much time they spent in finishing the entire look-up process because this requirement may impose unintentional pressure upon them to tackle the task as quickly as possible, which would then inevitably distort the “naturalness” of the conditions. The assignment is reproduced in full in Appendix 1, and a list of the looked-up lexical items (305 in total) is provided in Appendix 2. Appendix 3 provides the names of the 36 pieces (excluding the unnamed one) of reading materials chosen by the students for this assignment.

40 out of the 70 students submitted the assignment before the due date at the beginning of the spring semester, and 37 of the completed assignments were eligible for analysis. (The remaining three were unusable because the students did not record the complete contextual sentence for the looked-up word as was required). Since most of our freshmen graduated from foreign language high schools with distinguished academic performance in general, those who committed themselves to the dictionary consultation assignment were assumed to be the more motivated and thus also to be among the most competent English learners in their age group in China. So strictly speaking, the findings of this study should be considered as relevant in demonstrating the dictionary-using habits of highly competent and committed young Chinese students just embarking on their university study as English majors. The analysis conducted of the collected data was essentially a descriptive one, aiming to answer the following four central questions:

-

(1)

What types of dictionaries do the students use?

-

(2)

Which dictionaries do they use?

-

(3)

What are their dictionary look-up patterns and what specific consultation problems did they encounter in the look-up process?

-

(4)

What are their expectations of a good learner’s dictionary?

In the next part of this paper, the research findings will be presented first, followed by in-depth discussions of the results corresponding to each of the four questions.

3 Results and discussions

3.1 What types of dictionaries do the students use?

When asked in the survey to name the dictionaries they use, 37 students reported 149 dictionaries, yielding an average of 4 per person. Over 90 % of these dictionaries are in digital form. In sharp contrast, in Nesi and Haill’s (2002: 280) study conducted less than 15 years ago, “[o]nly two students listed electronic bilingual ‘translators’”. In this paper, the term “digital dictionary” (Lew and De Schryver 2014: 343) will be used as the cover term for electronic dictionaries in general. In categorizing these digital dictionaries named by the students, we adopted some key concepts from De Schryver (2003: 149–150). The major types identified include (1) pocket electronic dictionaries (PEDs), (2) mobile dictionaries (MDs), (3) internet dictionaries (IDs), and (4) computer electronic dictionaries (CEDs). Figure 1 demonstrates the distribution of dictionary types used by the students.

That the students should so remorselessly cast PDs behind the hedge of their memories may still seem a bit surprising, considering the fact that group purchase of learners’ dictionaries in paper form is still recommended and a fairly common practice in Chinese high schools and even universities (Chen 2010: 281). But then in this particular survey question, the students were asked to name the dictionaries they actually use, not those they buy and own on recommendation or otherwise. So it has become clear that left to themselves, very few Chinese students still use print dictionaries (PDs). And if this is the case with students majoring in English, should we not expect those who major in other arts subjects to embrace digital dictionaries even more readily? This question then leads to the inevitable doubt over the necessity of spending more efforts comparing paper and digital dictionaries. Maybe we could even venture the suggestion that it is time pedagogical lexicography shifted its focus to areas such as the effect of various digital media on successful dictionary use and digital dictionary skills.

Pocket electronic dictionaries are so-called stand-alone dictionaries as they do not require any network connection. Nearly half of the digital dictionaries named by the students are PEDs, which corresponds to the consistent observation that PEDs are particularly popular with students from East Asia countries (Nesi 1999; Stirling 2003; Midlane 2005; Chen 2007; Lew and De Schryver 2014). Twenty years ago, Taylor and Chan (1994) reported that the English teachers they interviewed in Hong Kong had been doubtful about the already popular use of PEDs by their students. Studies on the use of PEDs in comparison with PDs by Chinese EFL students in the first decade of this century also demonstrated mostly negative effects of the former and often argued for more use of the latter in L2 learning (Deng 2006; Yang and Zhao 2007; Shu and Chen 2009). Apparently, this general distrust of PEDs among teachers, lexicographers, and researchers did not preempt the growing popularity of PEDs with language learners. This may have to do with the rapid improvements found in each new version of PEDs and the fact that the high-quality ones in these years are mostly based on the most reputable learners’ dictionaries overseas or authoritative bilingual dictionaries in China. In Chen’s (2010: 275) latest study of PEDs in EFL learning, she actually found that “there are no significant differences between PED and PD use in comprehension, production and retention of vocabulary although the speed of the former is significantly faster than the latter”. What is obvious is that the speedy access to information is the unbeatable aspect of PEDs that continues to draw more and more users, especially now that content-wise PEDs are as good as the PDs on which they are based.

We use “mobile dictionaries” to refer to dictionary applications that can be installed, usually for free, not only on mobile phones and other sundry mobile devices, but also on robust machines, such as desktop and laptop computers. They can also be accessed both on- and off-line. The “hybrid” dictionary product prophesized by De Schryver (2003: 150) seems to have actually materialized in dictionary apps. And MDs are apparently becoming increasingly popular with our student users, especially because more and more of them own a smartphone now.

On the other hand, internet dictionaries are not half as popular as either PEDs or MDs though with the advent of tablets and smartphones they are almost as easily accessible as any hand-held dictionaries. From some of the students’ comments, we found that the major problem with IDs is that their definitions and examples are not considered reliable enough. It seems that 12 years since they were described as “the result of sloppy and hasty compilations” (De Schryver 2003: 160) IDs still have not improved much in terms of status. This is, however, not very surprising considering that some IDs in China actually claim that no human intervention in the selection of examples is made. A second reason might be that without network connection, IDs simply cannot be used, while MDs are also usable off-line though with less information available than when connected to the internet.

“Computer electronic dictionaries” here refer to both in-built dictionaries (often in Mac computers) and dictionary software which can only be run on computers. They are all stand-alone dictionaries and yet not as portable as PEDs. Actually, of the 6 named CEDs, 5 are in-built ones and 1 free downloaded software. It seems that in spite of the fact that learners’ dictionaries in software or on CD-ROM attracted more attention from lexicographers and researchers (Nesi 1999: 59), they have never been really popular with Chinese students. And now with the encroachment of MDs, CEDs in general are quickly losing the last bit of ground they ever managed to hold. Figure 2 illustrates these four types of digital dictionaries in terms of media (hand-held devices vs. robust machines) and access pattern (off-line vs. online).

At the moment, the PED is the dominant type of dictionaries used among students. But with the rapidly increasing popularization of smartphones and other mobile devices (tablets, ebooks such as Kindle, and the emerging i-watches and google glasses), perhaps it would not be long for MDs to overtake PEDs. We are also going to see that the dictionaries frequently used by students in PED form are highly homogeneous and do not appear in the app form. This makes one wonder: should these dictionaries one day be developed into apps, would the students not download and install them first thing onto their mobile devices and cast behind their PEDs as fast as they did with their PDs?

3.2 Which dictionaries do the students use?

As could have been expected, certain dictionary titles keep coming up in different lists. The followings are the dictionaries most frequently named by the students:

Oxford Advanced Learner’s English-Chinese Dictionary (7th ed., PED and PD, bilingualized) 24

English-Chinese Dictionary (2nd ed., PED, bilingual) 18

Youdao Dictionary (MD, bilingualized) 13

Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (4th ed., PED, bilingualized) 12

Merriam-Webster Dictionary (MD, monolingual) 12

Dictionary.com (MD, monolingual) 9

Jinshanciba Dictionary (MD, bilingualized) 8

Eudic (MD, bilingualized) 7

Chinese-English Dictionary (3rd ed., PED, bilingual) 7

The three most common forms of dictionaries, namely, bilingualized, bilingual, and monolingual, are all used by the students. In terms of directionality, however, only one Chinese–English dictionary is named, and merely by 7 students out of 37. It seems that English majors in general use English–Chinese dictionaries far more often in their studies, though when asked to describe the purposes of their dictionary use, all of them included composing an article in English, a most typical encoding task.

When asked to give the title of the most frequently used dictionary, 16 of the students named the bilingualized OALECD. The bilingual ECD came in second (7). Table 1 sets out the ten most popularly referred-to dictionaries with the number of students who named them, according to dictionary types.

From the table, we see that about 62 % of the students actually prefer using bilingualized dictionaries. Many of them quoted the availability of both L1 and L2 definitions as the foremost merit of the BLDs they use and described them as “mutually complementary”. This testifies to the finding of Chen’s (2011: 161) studies on BLDs that “Chinese students are inclined to read both L1 and L2 parts available in BLD entries rather than only one part of them”. Meanwhile, OALECD is by far the most popular dictionary with our English majors. More than half of the users claimed that they started using OALECD as recommended by their high school or even primary school teachers and have been using it for a long time. It is thus likely that those who use the OALECD in PED chose the particular PED because it contains this dictionary.

A closer reading of the surveys reveals that it is the CASIO PED (different models) that our students all use. It also contains the bilingual ECD, the second most frequently named dictionary. Although this PED brand is described as “expensive” and “affordable to only a handful of students” 5 years ago (Chen 2010: 282), it is apparently becoming more affordable to Chinese students now. Two of the four students who use the paper OALECD expressed the intention of buying a PED containing the same dictionary for the natural consideration of “convenience”. For English majors who have to complete study tasks daily making use of dictionaries, the portability and efficiency in consultation of a PED must have appeared almost irresistible. Nevertheless, it seems that their choice of a PED is still largely determined by what dictionaries it contains.

On the other hand, an equal number of students (19 %) prefer bilingual and monolingual dictionaries, respectively. Those who named the bilingual ECD all used it in PED and cited “authority” and “inclusiveness of headwords” as its chief merits. All of the monolingual dictionaries come in MD form, and students favoring them are more likely to offer some individual reasons. For instance, the Merriam-Webster dictionary (app) is said to have “detailed and clear differentiation among senses”. Both Dictionary.com (app) and Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English (app) are liked for “etymology treatment” and “nice layout”. Other reasons include “pictorial illustrations” and even “free of charge”.

Many students when giving comments on the most-used dictionary cited “clarity of definition”, “synonyms and antonyms”, “word-formation information”, “idiom and set phrase treatment”, and “collocation illustration” (in the order of frequency) as reasons for preferring the dictionary. Since the curriculum in the English department at Fudan University lays much emphasis on building up vocabulary through word-formation and synonym/antonym exercises, as well as the importance of learning collocations, our students very likely have incorporated these guidelines into their own dictionary use activities without ever being systematically trained to. Considering also that all of the 37 students claimed that they use dictionaries everyday and for all their English classes and when completing all sorts of study tasks, it can be concluded that dictionaries do still play a very important role in language learning for Chinese students majoring in English today. Except for two students who named paper OALECD as their most-used dictionary, all the rest admitted carrying either PEDs or MDs with them everywhere they go. So if anything, dictionaries are actually becoming even more useful and usable to language learners, thanks to the digital medium. Hence, the need to run a course on dictionary use in our English department seems even more pressing now.

Except for one, all of the students described both strong and weak points of their most-used dictionaries. It seems very likely that Zaenen’s (2002: 239) prediction of dictionaries being no longer viewed as the absolute authority with the change of their format has come true after all. Meanwhile, it is not very surprising that the few students who named paper OALECD all cited its paper form as a major or only defect. With OALECD in PED, the repeatedly mentioned drawback is its insufficient coverage of words. The bilingual ECD is criticized for its inevitable feature—not offering English definitions. Yet, the most noteworthy finding is that nearly all the students said that the drawbacks of their most-used dictionary can be compensated for by other dictionaries. As a matter of fact, all PEDs contain multiple dictionaries and with MDs you can practically install as many as you want to in the same mobile device. The availability of multiple dictionaries and thesauruses is definitely an unbeatable advantage of the digital dictionary form. This could perhaps throw some new light on studies of dictionary use; for instance, maybe today’s dictionary users would become more and more interested in knowing how to make good and efficient use of multiple dictionaries at the same time.

3.3 Outcomes of dictionary consultation

In total, 307 words were looked up and recorded by the students (33 students looked up 8 words as instructed, and one 14, another 11, two 9). Interestingly, only two of the four students claiming the paper version of OALECD as the most-used dictionary actually used this dictionary for completing the consultation assignment.

Though asked to look up only eight words, nineteen of these students (51.4 %) admitted to having used more than one dictionary. Of the six students who appeared to have found the correct contextual meaning for all of the words, four used multiple dictionaries. Figure 3 illustrates the numbers of students successful with the consultation of all of the 8 words, with 7 words, and less than 7, and the respective rates of students using more than one dictionary.

Generally speaking, it is true that students are more likely to find the correct meaning for the word if it is a noun, especially a proper noun. But none of the six students who had complete success with eight words looked up nouns only. So the following tentative suggestion would be ventured after all: it seems that using more than one dictionary at the same time facilitates efficient consultation and thus leads to a better chance of finding correct contextual meanings. Making use of multiple dictionaries is convenient in various digital media. And more than half of our English majors are already in the process of forming this habit as shown in the survey results. What they need seem to be (1) more encouragement to make use of multiple dictionaries for more effective consultation and (2) guidance in exploring the shortest “access routes” to the most relevant data (Bergenholtz et al. 2009), transferring between different dictionaries.

3.3.1 Dictionary look-up patterns

A close examination of the dictionary consultation results shows that the look-up patterns followed by students are highly complex and individual, quite in line with the overall observation made by Thumb (2004) in her study of dictionary look-up strategies among users of the bilingualized learner’s dictionary. 15 of the students recorded both L1 translations and L2 definitions for the same word, 14 L1 translations only, and 8 L2 definitions only. Considering that more than half of them used multiple dictionaries with an even higher percentage of bilingualized dictionaries involved, it is significant to note that the number of students actually making use of both L1 and L2 parts is 40.5 %. In other words, it seems that students are inclined to rely on Chinese equivalents either alone or in combination with English definitions much more than on the latter alone, maybe more than they are aware of themselves. Chen (2007) discovered in her survey with 800 English majors in eight Chinese universities that 53.3 % of them considered bilingualized dictionaries as more useful than bilingual and monolingual ones. In the survey part of this study, many of the students also praised their most-used bilingualized dictionary for its provision of English definitions. But this apparently is what the students thought, and the consultation results reveal that when actually using dictionaries, many of them must have found Chinese equivalents more useful at least for comprehension. Actually, two of the seven students who seemingly favored L2 definitions only also included Chinese equivalents for one term each: “thyroid gland” and “cardiogram”. The one looking up “thyroid gland” commented that he had to turn to an English-Chinese dictionary because the English definition contained words of anatomy “too difficult to understand”. Voices favoring the role of translation equivalents and bilingual practice in the language learning process actually started being heard more often in literature of the last 5 years (Butzkamm 2009; Cook 2010; Nation 2011; Levine 2011; Augustyn 2013). From the results of this study, it may also be suggested that with technical terms, students ought to be advised to go directly to the bilingual dictionary available in their mobile device for more efficient consultation.

At the same time, it is also observed that the consultation by students recording both L1 and L2 parts of the entry tends to be more conscientiously and laboriously done than otherwise. Even the students recording only L2 definitions prove to be more industrious than those recording only L1 translations. The last group is most likely to use one bilingual dictionary alone. The rates of successful consultation by the three groups tell the story: L1 and L2—26.7 %; L2 only—12.5 %; L1 only—7.1 %. Of course hardworking students are more likely to be good dictionary users. Still students in general need to be encouraged to make more use of L2 definitions especially with words of more abstract meanings, because these words naturally have Chinese equivalents that are at least equally abstract and thus elusive. For instance, the word “luminosity” was looked up by one student and she commented that the two English definitions in OALECD “the fact of shining in the dark; the ability to give out light” and “a clear and beautiful quality that something has” were much easier to distinguish, and it did lead her to the right choice of the second one. In comparison, the Chinese equivalents in the ECD are all close synonyms and difficult to differentiate, thus not of any help to her comprehension of the word’s contextual meaning.

None of the 37 students admitted to having taken any course or lecture dealing with the topic of lexicography or dictionary use. In contrast, nearly half of the students answered “yes” to the other survey question “whether they have read the front matters of any dictionaries they use”. Although personal reasons for doing this vary, one thing is certain that we dealt with a group of highly conscientious English learners who were amply interested in dictionaries per se in spite of their woefully limited exposure to any lexicographical teaching. Many of them actually recorded all the sub-entries listed in the dictionary for the headword, including different word classes. Since the students were asked to look up words completely unknown to them before, it is likely that they wanted to have an exhaustive reading of their meanings. Other dictionary information also likely to be recorded includes illustrative examples, idioms and phrases related to the headword, derivatives, and synonyms and antonyms. The recording compass varies from person to person and word to word; what is put down and what left out usually appears haphazard. Nevertheless, it seems that though lacking in systematic training in dictionary use, our English majors do look at and make use of dictionaries as an important vocabulary learning resource. In other words, making use of dictionaries does not guarantee good language learning results, but language majors, or the most conscientious if not necessarily the best language learners, must make good and frequent use of dictionaries. Put in yet another way, the more a learner’s dictionary is used, the more useful it is likely to be.

3.3.2 Dictionary look-up problems

It has to be stated that in this study students are expected to identify the correct dictionary sub-entry containing the contextual meaning for the looked-up word. Asking a first-year Chinese undergraduate to specify the meaning for each English word looked up in a dictionary would be too demanding at the moment, especially considering that they have nearly zero training in dictionary skills.

The following five categories of look-up failures were identified:

-

1.

Students chose the wrong dictionary sub-entry (15).

-

2.

Students admitted not being able to find the correct dictionary sub-entry (14).

-

3.

Students recorded multiple sub-entries and failed to indicate which one was found correct (12)

-

4.

Students chose the correct dictionary entry or sub-entry but rejected it as inappropriate for the context because of misinterpretation or confusion (10).

-

5.

The word or the appropriate meaning of the word was not found in the dictionary (10).

In Nesi and Haill’s (2002) study, the most common type of failures is choosing the wrong dictionary entry or sub-entry. In this study, no student chose the wrong entry, but still 15 cases of wrong sub-entry selection were found, constituting the most common type of look-up failures. These were all polysemous words, of which 4 were recorded for both L1 and L2 parts, 5 for L1 translations, and 6 for L2 definitions, respectively. So it seems that the wrong selection of a contextual meaning has little to do with whether students read L1 or L2 or both parts for the looked-up word.

With the majority of the cases in Nesi and Haill’s (2002: 282) study, the problem was due to the student’s failure to identify the word class of the looked-up word, but only two such cases were found in this study. For example, the word “harangue” is used as a verb in the context, but the student took it for a noun and chose the sub-entry “a speech addressed to a public assembly”. In the other case, the adverb “sotto voce” was mistaken as an adjective. This may be because that the students in this study are all English majors who have already acquired a relatively good command of grammar before entering university, and thus very few of them seem to encounter any problems identifying word classes.

In 8 cases, the first sub-entry was selected though the correct one was listed later. For two of these words, the wrong sub-entry was actually the only meaning provided by the bilingualized OALCED, but the correct one was included in the bilingual ECD which the student claimed to have used. These 8 cases are all listed in Table 2 (if the student recorded only L1 translations, their English meanings are provided in square brackets).

The contextual meanings of some of these words are either archaic (“dilate”), metaphorical than literal (“groove”), or relatively uncommon (“rod”). For “eke” and “hark”, both unusual verbs in themselves, the students failed to perceive it is the verbal phrases “eke out” and “hark back at” that they should have consulted, which have meanings different from the verbs standing on their own. For “adrenaline” and “ensconce”, the contextual meanings are so unusual that neither was included in the OALECD. It thus seems that these failures could hardly be all attributed to the students’ lack of dictionary-using skills. But they could definitely be instructed to read the dictionary information with more patience and scrutiny, and perhaps be encouraged to check another dictionary for a less than common word in case the contextual meaning is simply missing in the first dictionary.

With the other five words, the wrong sub-entry is not the first one to appear in the dictionary, and it is interesting to note that nearly all of them were given lengthy comments expressing the students’ uncertainty about this choice and why it was made nevertheless. The students were of course right in being suspicious about the wrong sub-entry, though their reasoning was mostly farfetched if not downright erratic. The bright side one sees in these cases is that there are students committed to making diligent use of dictionaries. A negative way of looking at it would point to the unfathomable user psychology which comes across as a discouragement to someone enthusiastic about teaching rational dictionary use. The five words are listed below (the source dictionary is given under the selected sub-entry due to space consideration) (Table 3).

The last word “cryptic” is perhaps an exception because the chosen sub-entry “abrupt; terse; short” was only found in the mobile app Dictionary.com used by the student. None of the other dictionaries checked by the researcher included this sense. Selection of a wrong sub-entry thus seems to be the result of various causes—the students’ insufficient command of English in general, their lack of training in locating a less frequent meaning of a word, as well as the dictionary’s failure to cover a word’s unusually metaphorical senses, or even the suspicious inclusion of a sense that the word may not have at all. The use of more than one dictionary available might be a good strategy after all for more effective dictionary use in the digital era.

The second category of look-up failures also involves polysemous words, consisting of 14 cases. In these cases, students confessed that they simply could not make out which sub-entry matches the word’s contextual meaning. 12 of these words were recorded for L1 translations, and 2 for L2 definitions. So it seems that the students are more likely to feel at a loss for which sub-entry to choose if they use bilingual dictionaries alone. As mentioned above, L1 translations do appear less helpful to students when they denote abstract and illusive concepts. These failed cases include such highly abstract and also polysemous words like “consortium”, “divination”, “intercourse”, “testimony”, “token”, etc. Students could certainly be encouraged to try another dictionary, either bilingualized or monolingual, to see if the L2 definitions can be of any help, and preferably with more illustrative examples.

But it also happens that the failure was due to the student’s insufficient command of grammar or to the fact that s/he was simply too work-shy. In one case, the student commented that he could not make out if “analog” in “Most analog electronic appliances, such as radio receivers, are constructed from combinations of a few types of basic circuits” is used as the adjective “模拟的” or the noun “类似物”. He then commented that this failure was caused by the dictionaries not providing illustrative examples. Although examples may indeed have helped, he should have known better about the word’s contextual grammatical role as an English major. The case of “mangy” in “If the boy we never had is strayed and stole, by the powers, call him Phelan, and see him hide out under the bed like a mangy pup …” was recorded for the word’s L1 definitions, and the student failed to find the contextual meaning because he did not take the necessary step to look up “mange” in the first sub-entry “having, caused by, or like the mange” when apparently he did not know the noun. Examples of type 2 selection failures are given in Table 4 (the source dictionary is given under the context sentence due to space consideration):

With the third category, the cases are considered as failures because no indication was given by the students as which sub-entry of the many recorded ones was his/her choice. Among the 12 cases, 4 were recorded for their L1 translations, 5 for L2 definitions, and 3 for both. It seems that the students very likely had forgotten to indicate the correct contextual meaning or simply assumed that the choice was too obvious.

As above mentioned, many students liked to record all of the word’s dictionary sub-entries and quite a few number of them did not indicate clearly their choice of the one appropriate to the contextual meaning. If, however, certain recorded collocational information matches exactly the word’s contextual collocation, or a sub-entry other than the correct one illustrates the headword in word classes different from the contextual one, the case was considered as a successful consultation. For instance, one student put down “(1) intensely painful <pain, ache>; (2) embarrassing, awkward, or tedious” for the word “excruciating” which appeared in “‘I can finally walk and sit again without being in excruciating pain,’ Schuster says”. Although the student did not make it clear hat the first sub-entry was his choice, we can assume it to be the case because the dictionary collocational information “<pain, ache>” he chose to record is near identical with that in the text; hence, he ought to know the correct choice. The same student looked up “orderly” as in “Nursing assistants and orderlies each suffer roughly three times the rate of back and other musculoskeletal injuries as construction laborers”. Beside the correct Chinese noun translation 护理员 (‘attendant’), he also recorded the sub-entries for “orderly” as an adjective. However, it was assumed that his English knowledge was sufficient enough to tell that “orderlies” is a noun in the context, and thus the adjectival senses were included only for the purpose of learning the word. Examples of type 3 selection failures are given in Table 5 (the source dictionary is given under the context sentence due to space consideration).

The student’s failure to indicate his/her sub-entry selection does not necessarily mean that s/he was not successful at locating the correct contextual meaning. It nevertheless points to poor dictionary consultation habits and sloppiness or messiness in dictionary use resulted from a lack of systematic training in dictionary skills. These students are hardworking enough to record different sub-entries for the looked-up word, and maybe as English majors they did this with a view to acquiring as much knowledge about individual words as possible. But they need to be trained in prioritizing dictionary information so as to make more efficient use of the dictionary for different consultation purposes.

Category 4 failures are the cases in which the students chose the correct dictionary entry or sub-entry but failed to identify the sense as contextually appropriate. In this connection, confusions were expressed (5), erroneous interpretations were given (3), or the right meanings were simply rejected (2). Interestingly, none of these cases involve highly polysemous words. Nesi and Haill (2002: 289) found that when students interpreted the correct entry or sub-entry wrongly, the words often had taken on a metaphorical meaning. But the looked-up words that our students failed to comprehend fully do not seem to take on any unusual metaphorical meanings. It was then found that of the 10 cases, 9 were recorded for L1 translations and 1 for L2 definitions. So it seems again that students are more likely to encounter difficulty locating the correct contextual meaning if they read L1 translations alone.

The correct Chinese translations 未受攻击的 (‘not attacked’) for “unassailed” and 安慰 (‘comfort’) for “solace” were rejected by the student as “inappropriate for the context”. It seems that some Chinese students had the unrealistic expectation that bilingual or bilingualized dictionaries would offer translational equivalents that fit perfectly into whatever context they had at hand. This is the same cause for the three cases of misinterpretation in which erroneous L1 translations were offered by the students who simply did not judge those available in the dictionary to be “appropriate” enough. In some other cases where the consultation had been successful, comments were also found expressing dissatisfaction with the L1 equivalents on the ground that they did not seem right for translating the word in the context. This may be because as native speakers of Chinese, students feel entitled to make judgments over L1 translations. The ever-expanding storage capacities for dictionaries must have also contributed to the user’s expectation of more and better choices of ready-made translational equivalents. But it also shows a lack of knowledge about micro-lexicographic matters on the users’ part. A bilingual dictionary offers L1 translations but ought by no means to be expected to act also as a monolingual thesaurus. It is neither practical nor actually possible for the translational equivalents offered in a dictionary to fit just any specific individual contexts.

Table 6 lists the 5 cases in which students expressed confusion over the contextual meanings of the looked-up items. Again the problem seems to be rooted in the students’ habit of reading only L1 translations. Even the one student recording L2 definitions for “punchline” expressed her regret over failing to find a good Chinese translation. It seems that by instinct EFL learners feel secure only when a certain new word is paired with some counterparts in their own language. Hence, it would not make much sense trying to discourage students from reading L1 parts in the dictionary, because they will always want to read them. But in a course of teaching dictionary use, the students could at least be alerted to the danger of missing the correct contextual meanings of lexical terms if they simply follow their habit of relying too heavily on L1 translations alone. Furthermore, they could be guided to acquire more skills in reading both L1 and L2 parts in the same dictionary and to explore the use of monolingual dictionaries along with their beloved bilingual ones.

There are altogether ten cases in which the students claimed that the looked-up word or the proper sense of the word was not found in the dictionaries used. The word “extortioner” was reported to be missing, whereas it was actually included as an entry word in the CED which the student said he used along with the OALECD. The words “mackerel”, “pickerel”, and “twirly-whirly” were not found in any of the seven dictionaries the student claimed she had used, which is understandable considering that the text chosen for this assignment was the story “How the Whale Got His Throat” from Kipling’s Just So Stories, a book almost as famous as Alice in Wonderland for the liberty the authors took in coining novel lexical terms. Both “prototypically” and “archetypically” were treated as run-on entries, and the student said she had difficulty in understanding the whole sentence only with the Chinese translations for “prototype” and “archetype”. But one could hardly blame the bilingual dictionary the student used for not providing translational equivalents for these two adverbial forms. This brought us again to the question of unrealistic expectations for learners’ dictionaries and the importance of educating students on the limits of what dictionaries can do for language learning.

The student who failed to find verbal senses for both “leverage” and “bookend” used the OALECD and simply stated the fact without any further comment. The two really “missing” words are “moralizer” and “incommunicable”. The student could not find “moralizer” in the bilingual paper dictionary he chose to use, which was also the only dictionary in this survey that was a 1977 edition. “Moralize” was then looked up instead and with a little guesswork, the student was apparently satisfied with the results. The contextual meaning of “incommunicable” was also guessed right by the student. It is not very surprising that these students all used only one dictionary. Of the 307 looked-up words, only two were actually not found and two had a less than usual sense missing in the dictionaries used.

To sum up, from these consultation outcomes, it can be observed that students with different habits of reading L1, L2, or L1 + L2 parts of the dictionary entry stand a roughly equal chance of choosing the wrong sub-entry for the contextual meaning of the looked-up word. Those who favor L1 translations did tend to experience difficulties more often in making choices between sub-entries. For one thing, L1 translations are not particularly helpful in sense differentiation especially with words denoting abstract concepts. Yet, for another, these students are also likely to be not as hardworking or driven as those who are in the habit of consulting L2 definitions or both L1 and L2 parts of the dictionary. Hence, their general command of English and dictionary-using skills may be more or less insufficient in comparison, leading to more confusions experienced in the consultation process.

3.4 What dictionaries do the students want?

In the last part of the survey, students were asked to talk about what they think are the essential qualities of a good dictionary based on their own dictionary-using experiences. It may not be very surprising that quite a few of them gave an almost exhaustive list of features that any one of the “Big Five” learners’ dictionaries would happily claim to have. This may be due to the fact that as competent English learners, these students have long been used to paying close attention to the many important aspects of language learning, and now as English majors, they are experiencing an ever-growing intimacy with dictionaries in their daily studies. Equally predictable is a common awareness of the need to consult multiple dictionaries, as is already manifest from the findings of the earlier parts in this survey.

A few of the students mentioned the importance of reading L2 definitions rather than L1 translations in dictionaries, and thus the superiority of bilingualized dictionaries in their eyes. One of them even said that she was aware that she often read only L1 translations in the bilingualized dictionary and this habit must be corrected. So it seems that students at large must have accepted the indoctrination of the supposed harmfulness of relying on L1 translations in language learning, which explains the higher percentage of bilingualized dictionary ownership.

A handful of the students predicted the inevitable and total replacement of paper dictionaries by digital ones. One of them described an ideal future online dictionary which is linked to huge corpora of live examples illustrating each sense of each word in specific contexts. Another student talked about “letting the user be the decision-maker”, suggesting that the dictionary makers do not decide what information to offer and what to omit. It seems that the younger generations of dictionary users are indeed becoming more confident and ambitious about what they want from dictionaries.

At the same time, there are also more levelheaded students commenting on the importance of finding the right dictionaries for English learners of different levels of competency. It is very interesting to note that several students emphasized how essential it is for senses of entry words to be arranged according to their frequency, and yet one student made an unequivocal statement that a dictionary is only good if it arranges all the word senses in a chronological order. Although the young students’ ideas of a good dictionary may seem to be poles apart, one thing is for sure—the age we live in is no longer a D 2 U (dictionary-to-user) but a U 2 D (user-to-dictionary) one. Over the years, scholars interested in future dictionaries have discussed and predicted the possibility of individualization or customization of dictionaries (Dodd 1989; Atkins 1996; Whitelock and Edmonds 2000; De Schryver 2003; Lew and De Schryver 2014). With the ever more flexible functions of dictionary apps in fast development, it may take less time than we are able to imagine for users to develop highly individualized patterns or routes of dictionary use. And one thing a teacher could explore with the students in a course on dictionary use would be perhaps how to create your own smart-dictionary which can, say, arrange the senses in a way that feels and proves most conducive to your own English learning.

4 Conclusion

This study has attempted to offer a portrait of the dictionary-using habits and behaviors of some of the best twenty-something English learners in China today. The empirical evidence sought and found in the dictionary consultation assignment designed for this study will be used to aid the development of a dictionary course for second-year undergraduates at the English department at Fudan University.

As veteran English learners, all of the students claimed that they use dictionaries everyday for various study tasks and purposes, and often more than one dictionary at a time. It seems that dictionaries play an indispensable role in the students’ English learning activities, and a sense of dictionary user is also on the rise judging from the confidence with which the young men and women talked about reasons for choosing the most frequently used dictionary and the fact that about half of them actually took time getting acquainted with the front matter in a dictionary.

The most unequivocal finding based on the survey results is the inevitable and total replacement of paper dictionaries by digital ones in students’ everyday study life. In the next few years, the question would simply be which type of digital dictionary will eventually be the victor, the now most popular pocket electronic dictionaries, or the speedily emerging dictionary applications, or the online dictionaries, term-banks, and word-finders whose potentials are still just being tapped?

Based on a meticulous examination of the consultation outcomes, it is found that in spite of the common awareness of the advantage of bilingualized dictionaries containing both L1 translations and L2 definitions, an instinctive reliance on or affinity to L1 translations can still be perceived. It thus seems unnecessary if not downright pointless to discourage students from reading L1 translations for looked-up words. Rather, they ought to be further enlightened on the advantages of reading both L1 and L2 parts in bilingualized learners’ dictionaries, and be encouraged to make use of multiple dictionaries of different types, a practice highly impractical with paper dictionaries but now most convenient with the digital medium and proved to be a constructive dictionary-using skill in this study.

On the other hand, Chinese students seem to have much higher demands and expectations on L1 translations in bilingual or bilingualized dictionaries, even to the extent of being unreasonable. It is a fact today that the younger generation of users no longer takes the authority of dictionaries for granted and is becoming increasingly more critical and ambitious about what they want from dictionaries. The involvement of users in shaping the dictionary for tomorrow is a tendency not to be resisted or resented but rather encouraged and exploited. This then leads to the question of how to improve the competence and qualification of dictionary users as future dictionary co-makers, a question fit for more consideration also for the dictionary course designing at Fudan.

Meanwhile, this study has a few limitations. First of all, the questionnaire-based survey as a research method in lexicographic studies has long been criticized for its unreliability and lack of scientific warranty (Hatherall 1984; Tarp 2009). It is especially difficult to guarantee that these dictionary consultation results all came from a completely independent look-up process since the assignment was designed to be carried out at home so as to ensure more natural conditions for dictionary use. Secondly, the participants were all first-year English majors at the same university, thus constituting a quite homogeneous user group. So the conclusions have to be treated with caution regarding its validity and applicability to the more generic group of young Chinese English learners as dictionary users. Thirdly, only their dictionary use for the decoding purpose of finding meanings for new words is studied, though students who do use dictionaries ought to use them no less often for various encoding activities. How well does the same group of students use their dictionaries for learning tasks like translation and composition? Would they consult more dictionaries than when performing reading tasks only? Would they still turn to L1 translations involuntarily even if what they want to accomplish is a piece of English writing? These questions could perhaps be pursued after the course on lexicography gets launched in the Fudan English department where students interested in lexicographic matters can be recruited more readily as participants for future user researches.

All in all, this study confirms to a large extent the usefulness of dictionaries in the digital era as a language learning resource for very competent young English learners in China and their general lack of a systematic dictionary training background. Reinforced thus is the urgent need of developing dictionary courses targeted at university English majors, with a view to providing professional guidance in dictionary knowledge and skills alike, and exploring the increasingly individualized concepts of dictionaries for tomorrow. Although the development of technology tends to liberate more and more the brain strength needed in both making and using dictionaries, it is always the person behind technology, the brain of the user/lexicographer, that actually shapes the future of dictionaries.

References

Dictionaries cited and their abbreviations

Chinese-English Dictionary. 3rd ed. (CED). 2010. Ed. Guanghua Wu. Shanghai: Shanghai Yiwen Press.

Dictionary.com. Since 2008. Oakland: Dictionary.com LLC. http://dictionary.reference.com/ [monolingual, online].

English-Chinese Dictionary. 2nd ed. (ECD). 2007. Ed. Gusun Lu. Shanghai: Shanghai Yiwen Press.

Eudic. Since 2013. Shanghai: Shanghai Qianyan Internet Technology. http://dict.eudic.net/ [bilingual, bi-directional, app.].

Jinshanciba Dictionary. Since 2008. Beijing: Kingsoft. http://www.iciba.com/ [bilingual, bi-directional, app.].

Mac in-built Dictionary. Cupertino: Apple. [bilingualized].

Merriam-Webster Dictionary. (MWD). 2013, 2015. Springfield: Merriam-Webster. http://merriam-webster.com/ [monolingual, app.].

Oxford Advanced Learner’s English-Chinese Dictionary. (OALECD). 2008. Eds. Shenghua Jin, et al. Trs. Yuzhang Wang, et al. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [bilingualized from the 7th edition of OALD].

Oxford Chinese Dictionary. 1st ed. (OCD). 2010. Eds. Julie Kleeman, and Harry Yu. Oxford: Oxford University Press, in association with FLTRP Beijing. [bilingual, bi-directional].

Youdao Dictionary. Since 2007. Wangyi Youdao Information & Technology. http://dict.youdao.com/ [bilingual, bi-directional, app.].

Other works

Atkins, B.T.S. 1996. Bilingual dictionaries: past, present and future. In Euralex’96 Proceedings I–II, Papers submitted to the Seventh EURALEX International Congress on Lexicography in Goteborg, Sweden, eds. Gellerstam, M., et al. Gothenburg: Department of Swedish, Goteborg University. 515–546.

Atkins, B.T.S. and K. Varantola. 1998. Language learners using dictionaries: the final report on the EURALEX/AILA research project on dictionary use. In Using dictionaries (Lexicographica Series Maior 88), ed. Atkins, B.T.S. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. 21–82.

Augustyn, P. 2013. No dictionaries in the classroom: translation equivalents and vocabulary acquisition. International Journal of Lexicography 26(3): 362–385.

Béjoint, H. 1981. The foreign student’s use of monolingual English dictionaries: a study of language needs and references skills. Applied Linguistics 2(3): 207–222.

Bergenholtz, H., S. Nielsen, and S. Tarp. 2009. Lexicography at a crossroads: dictionaries and encyclopedias today, lexicographical tools tomorrow. Bern: Peter Lang AG.

Butzkamm, W. 2009. The bilingual reform: a paradigm shift in foreign language teaching. Tübingen: Günter Narr Verlag.

Chen, Y. 2007. A survey of English dictionary use by English majors in Chinese universities. Lexicographical Studies 2: 120–130.

Chen, Y. 2010. Dictionary use and EFL learning. A contrastive study of pocket electronic dictionaries and paper dictionaries. International Journal of Lexicography 23(3): 275–306.

Chen, Y. 2011. Studies on bilingualized dictionaries: the user perspective. International Journal of Lexicography 24(2): 161–197.

Cook, G. 2010. Translation in language teaching: an argument for reassessment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cowie, A.P. 1999. English dictionaries for foreign learners: a history. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Deng, L. 2006. Survey of the use of paper dictionaries and electronic dictionaries among college students. Lexicographical Studies 1: 172–181.

De Schryver, G.-M. 2000. The concept of “Simultaneous Feedback”: towards a new methodology for compiling dictionaries. Lexikos 10: 1–31.

De Schryver, G.-M. 2003. Lexicographers’ dreams in the electronic dictionary age. International Journal of Lexicography 16(2): 143–199.

De Schryver, G.-M., and D. Joffe. 2004. On how electronic dictionaries are really used. In Proceedings of the Eleventh EURALEX International Congress, EURALEX 2004, Lorient, France, July 6–10, 2004, eds. Williams, G., and S. Vessier. Lorient: Faculte des Lettres et des Sciences Humaines, Universite de Bretagne Sud. 187–196.

De Schryver, G.-M., D. Joffe, P. Joffe, and S. Hillewaert. 2006. Do dictionary users really look up frequent words?—on the overestimation of the value of corpus-based lexicography. Lexikos 16: 67–83.

Ding, J. 2008. Bottom-up editing and more: the E-forum of the English–Chinese dictionary. In Proceedings of the XIII Euralex International Congress, EURALEX 2008, Barcelona, Spain, July 15th–19th, 2008, eds. Bernal, Elisenda, and Janet DeCesari. Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra. 339–343.

Dodd, W.S. 1989. Lexicomputing and the dictionary of the future. In Lexicographers and their works. (Exeter Linguistic Studies 14), ed. James, G. Exeter: Exeter University Press. 83–89.

Dziemianko, A. 2010. Paper or electronic? The role of dictionary form in language reception and retention of meaning and collocations. International Journal of Lexicography 23(3): 257–273.

Dziemianko, A. 2011. Does dictionary form really matter?’ In Asialex 2011 Proceedings. Lexicography: theoretical and practical perspectives, eds. Akasu, K., and S. Uchida. Asian Association for Lexicography. 92–101.

Dziemianko, A. 2012. Why one and two do not make three: dictionary form revisited. Lexikos 22: 195–216.

Hartmann, R.R.K. 1994. Bilingualized versions of learners’ dictionaries. Fremdsprachen Lehren und Lernen 23: 206–220.

Hatherall, Glyn. 1984. Studying dictionary use: some findings and proposals. In LEXeter ’83 Proceedings. Papers from the International Conference on Lexicography at Exeter, 9–12 September 1983. (Lexicographica Series Maior 1), ed. Hartmann, R.R.K. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer. 183–189.

Kan, H., and Y. Wang. 2003. Survey of dictionary use by English majors in Shanghai University. In Bilingual dictionary studies, ed. Zeng Dongjing. Shanghai: Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press. 391–399.

Kaneta, T. 2011. Folded or unfolded: eye-tracking analysis of L2 learners’ reference behavior with different types of dictionary. In Asialex 2011 Proceedings. Lexicography: theoretical and practical perspectives, eds. Akasu, K., and S. Uchida. Asian Association for Lexicography. 219–224.

Kobayashi, C. 2008. The use of pocket electronic and printed dictionaries: a mixed-method study. In JALT 2007 Conference Proceedings, eds. Bradford Watts, K., et al. Tokyo: JALT. 769–783.

Lang, J., and J. Li. 2003. A survey of English dictionary use. Journal of Beijing International Studies University 6: 54–60.

Laufer, B., and M. Kimmel. 1997. Bilingualized dictionaries: how learners really use them. System 25(3): 361–369.

Levine, G. 2011. Code choice in the language classroom. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Lew, R. 2004. Which dictionary for whom? Receptive use of bilingual and semi-bilingual dictionaries by Polish learners of English. Poznan: Motivex.

Lew, R., and G.-M. de Schryver. 2014. Dictionary users in the digital revolution. International Journal of Lexicography 27(4): 341–359.

Lew, R., M. Grzelak, and M. Leszkowicz. 2013. How dictionary users choose senses in bilingual dictionary entries: an eye-tracking study. Lexikos 23: 228–254.

Li, Z. 2009. On English majors’ use of dictionaries. Journal of Guangdong University of Foreign Studies 20(6): 97–100.

Midlane, V. 2005. Students’ use of portable electronic dictionaries in the EFL/ESL classroom: a survey of teacher attitudes. Available at http://www.bankgatetutors.co.uk/PEDs.htm.

Müller-Spitzer, C., A. Koplenig, and A. Topel. 2012. Online dictionary use: key findings from an empirical research project. In Electronic lexicography, eds. Granger, S., and M. Paquot. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 425–457.

Müller-Spitzer, C., Koplenig, A., and A. Topel. 2014. Evaluation of a new web design for the dictionary portal OWID. An attempt at using eye-tracking technology. In Using online dictionaries. (Lexicographica Series Maior 145), ed. Müller-Spitzer, C. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. 207–228.

Nation, I.S.P. 2011. Research into practice: vocabulary. Language Teaching 44(4): 529–539.

Nesi, H. 1999. A user’s guide to electronic dictionaries for language learners. International Journal of Lexicography 12(1): 55–66.

Nesi, H., and R. Haill. 2002. A study of dictionary use by international students at a British university. International Journal of Lexicography 15(4): 277–305.

Shu, Z., and Y. Chen. 2009. Effects of dictionary use on English vocabulary acquisition: traditional dictionaries and portable electronic dictionaries. ACTA Academiae Medicinae Zunyi 32(4): 429–431.

Simonsen, H.K. 2009. Vertical or horizontal? That is the question: an eye-track study of data presentation in internet dictionaries. Eye-to-IT conference on translation processes. Frederiksberg: Copenhagen Business School.

Simonsen, H.K. 2011. User consultation behaviour in internet dictionaries: an eye-tracking study. Hermes 46: 75–101.

Stirling, J. 2003. The portable electronic dictionary: faithful friend or faceless foe? Available at http://www.elgweb.net/ped-article.html.

Tang, G. 1997. Pocket electronic dictionaries for second language learning: help or hindrance? TESL Canada Journal 15(1): 17–21.

Tarp, S. 2009. Reflections on lexicographical user research. Lexicos 19: 275–296.

Taylor, A., and A. Chan. 1994. Pocket electronic dictionaries and their use. In Proceedings of the 6th EURALEX International Congress, eds. Martin, Willy. et al. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit. 598–605.

Thumb, J. 2004. Dictionary look-up strategies and the bilingualized learner’s dictionary. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Tono, Y. 1989. Can a dictionary help one read better? In Lexicographers and their works. (Exeter Linguistics Studies 14), ed. James, G. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. 192–200.

Tono, Y. 2011. Application of eye-tracking in EFL learners’ dictionary look-up process research. International Journal of Lexicography 24(1): 124–153.

Whitelock, P., and P. Edmonds. 2000. The sharp intelligent dictionary. In Proceedings of the Euralex International Congress, EURALEX 2000, Stuttgart, Germany, August 8th–12th, 2000, eds. Heid, U., et al. Stuttgart: Institut für Maschinelle Sprachverarbeitung, Universität Stuttgart. 871–876.

Yang, B., and J. Zhao. 2007. A contrastive study of paper dictionaries and palmtop dictionaries in collocation. Hope Monthly 2: 21–22.

Yu, W. 1999. Survey of the use of English–Chinese and Chinese–English dictionaries. Journal of Guangzhou Normal University 12: 88–93.

Zaenen, A. 2002. Musings about the impossible electronic dictionary. In Lexicography and natural language processing: a festschrift in honour of B. T. S. Atkins, ed. Correard M.-H. EURALEX. 230–244. Available at: http://www.ims.unistuttgart.de/euralex/.

Zarei, A.A. 2010. Cognitive semantics and multidimensional definition for a new generation of bilingual/bilingualized learner’s dictionaries. Journal of Foreign Language Teaching and Research 42(5): 374–379.

Zhang, P. 2004. Is the electronic dictionary your faithful friend? CELEA Journal 27(2): 23–28.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1 Dictionary consultation assignment

-

1.

About the dictionaries you use

-

(a)

Which dictionaries do you currently use? Please give the name, date of publication, and type (in print or digital form).

-

(b)

Which dictionary do you use the most for your English study? Please describe the dictionary as closely as possible (How did you come by it? What makes you want to keep using it? Are you considering replacing it? Why or why not?).

-

(c)

How often do you use a dictionary? When do you use it: when doing assignments? Or at other times? For what purposes do you use it?

-

(d)

Do you carry your dictionary/dictionaries with you, to classes, to the library, or to other places?

-

(e)

Have you ever read the front matter in a dictionary? If you have, why? Have you ever sat in a course or lecture devoted to dictionaries or lexicographical topics in general?

-

2.

Please choose a short text from any source which must contain eight items of vocabulary with which you were completely unfamiliar before reading.

-

(a)

Look up the words/phrases in your dictionary/dictionaries as you normally do. Identify the dictionary/dictionaries.

-

(b)

Record the look-up process as faithfully as possible. Give the contextual meanings of the 8 words/phrases. Explain if there are any problems you have in finding the correct meaning of the item (try to be specific).

-

3.

What are your ideas about a good/useful dictionary?

Appendix 2 Words looked up by students

A | |||

aberration | abiding | acrimony | adrenaline |

agitate | alien | aloof | ambivalence |

analog | analogy | apocryphal | apprentice |

arch | archetypically | archly | armature |

armistice | askew | assault | aversion |

avidity | |||

B | |||

bantering | basal | befoul | bequeath |

bookend | bough | bountiful | bracken |

breeches | briar | buffer | buffoon |

butler | |||

C | |||

calibrate | capacitor | cardiogram | cascade |

cataract | cathode | caucus | charade |

chardonnay | chop | circuit | clammy |

coax | cobbler | collie | composite |

congestive | confine | conjecture | consecrate |

consortium | cosmogony | cryptic | cunning |

D | |||

dab | dace | dandy | debase |

defiant | delirious | demeanor | derelict |

despot | detest | dilate | discretion (×2) |

distaste | disavowal | disposable | divination |

doublet | dungeon | ||

E | |||

eccentric | echelon | eke (out) | emaciated |

enigmatic | enmesh | ensconce | entity |

epitaph | epitome | equanimity | errand |

euthanasia | exasperation | excruciating | explicate |

exponentially | expurgate | extemporize | extortioner |

extravagant | |||

F | |||

fatalism | featherweight | filigree | flock |

fold | fondle | forestall | forlorn |

frailty | frantic | frenzy | |

G | |||

garfish | gastronomical | gaze | ghastly |

gnash | gong | graffito | gratuitously |

grossly | groove | ||

H | |||

hand-to-mouth | harangue | harbinger | hark |

hodgepodge | |||

I | |||

iconoclast | immune | impenetrable | impertinence |

incipient | incommunicable | indemnity | indescribably |

inexplicable | influx | inkling | innocuous |

insight | in situ | in tandem | intentioned |

intercourse | interiority (×2) | intermediate | interminable |

intoxication | intrepidity | introspective | irrevocable |

irrevocably | irruption | ||

J | |||

jackknife | jockey | ||

K | |||

kabbalist | |||

L | |||

lark (×2) | latch | lavish | legislator |

leverage | ludicrous | lull | luminosity |

lurk | luscious | ||

M | |||

macho | mackereel | majestic | maneuver |

mangy | manifest | manifestation (×2) | mantra |

maternal | matrimony | meekly | meekness |

meretricious | mirage | meticulous | moralizer |

musculoskeletal | muster | ||

N | |||

nay | nimble (×2) | node | nubbly |

nudge | |||

O | |||

omniscient | orderly | ostpolitik | outsoar |

over head and ears | overmatch | ||

P | |||

paraphernalia | parsimony | patriarchal | pediment |

penetrating | penury | perilous | persuasion |

pestilence | pew | pickereel | pivot |

plaice | platitude | pluck (at) | pontificate |

portcullis | practitioner | presumption | prototypically |

proximity | prudent | punchline | |

Q | |||

quadrivium | |||

R | |||

ransack | ransom | rationalization | reckon |

repartee | recluse | recurrence | reincarnation |

renege | repose | repository | reprieve |

retard | rhapsody | rod | rumble (on) |

rumple | |||

S | |||

sackcloth | sagacity | salient | saunter |

scattered | scent | scion | serene |

sinew | sinewy | slant | slippery |

snooty (×2) | solace | soliloquize | sotto voce |

spasm | specimen | speculative | spouse |

squat | statutory | stoutly | strata |

sullen | surly | surveillance | suspender |

sustenance | swank | swindle | systole |

T | |||

take heart | tantalize | tenacious | testimony |

thyroid gland (×2) | token | transient | transpire |

trespass | trifle | trod | trundle |

tumult | twirly-whirly | twofer | tyrannically |

U | |||

unassail | undefiled | unscathed | upheaval |

V | |||

veneration | vexation | villainous | volatility |

voracious | |||

W | |||

wade | wag | wail | whence |

wholesale | wisecrack | ||

Y | |||

yawn | |||

Appendix 3 Reading materials of the students’ choice

1.1 Fiction (20)

1.1.1 16 Novels (excerpts)

Jesus the Son of Man, Kahlil Gibran

Joan of Arc: A Life Transfigured, Kathryn Harrison

Just So Stories, Rudyard Kipling

Life of Pi, Yann Martel

Never Let Me Go, Kazuo Ishiguro

No Time for Goodbye, Linwood Barclay

Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen

The Da Vinci Code, Dan Brown

The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald

The Hobbit, J. R. R. Tolkien.

The Prophet, Khalil Gibran

The Screwtape Letters, C. S. Lewis

The Sun Also Rises, Ernest Hemingway

Vanity Fair, W. M. Thackeray

Walden, H. D. Thoreau

Wuthering Heights, Emily Brontë

1.1.2 2 Collections of short stories (excerpts)

After the Quake (collection of short stories, in translation), Haruki Murakami

Between Rounds (collection of short stories), O. Henry

1.1.3 2 Short stories

“The Gift of Maggie”, O. Henry

“Vanka” (in translation), Anton Chekhov

1.2 Nonfiction (16)

1.2.1 9 Articles

“A City of Many Pasts” (The New Yorker), Joseph Mitchell

“Fleeing Terror, Finding Refuge: Millions of Syrians Escape an Apocalyptic Civil War, Creating a Historic Crisis” (News story), Paul Salopek

“From Competence to Commitment”, Anonymous

“Hospitals Fail To Protect Nursing Staff from Becoming Patients” (News story), Daniel Zwerdling

“The Ideal English Major”, Mark Edmundson

“The Joy of Reading”, Anonymous

“The New Pan-Asian Order”, Evan A. Feigenbaum

“We Will Never Conquer Space”, Arthur. C. Clarke

1.2.2 8 Books (excerpts)

A Very Short Introduction to the Roman Empire (excerpts), Christopher Kelly.

Jewish Literacy: The Binding of Issac (excerpts), Rabbi Joseph Telushkin

Letters to a Law Student (excerpts), Nicholas J. McBride

On Prophesying by Dreams (excerpts, in translation), Aristotle

The Problem of China (excerpts), Bertrand Russell

The Renaissance: A Very Short Introduction (excerpts), Jerry Brotton

The Social Contract (excerpts, in translation), Jean-Jacques Rousseau

White House Years (excerpts), Henry Kissinger

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, J. A study of English majors in a Chinese university as dictionary users. Lexicography ASIALEX 2, 5–34 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40607-015-0016-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40607-015-0016-5