Abstract

Purpose of Review

Recent reports of a “loneliness epidemic” in the USA are growing along with a robust evidence base that suggests that loneliness and social isolation can compromise physical and psychological health. Screening for social isolation among at-risk populations and referring them to nature-based community services, resources, and activities through a social prescribing (SP) program may provide a way to connect vulnerable populations with the broader community and increase their sense of connectedness and belonging. In this review, we explore opportunities for social prescribing to be used as a tool to address connectedness through nature-based interventions.

Recent Findings

Social prescribing can include a variety of activities linked with voluntary and community sector organizations (e.g., walking and park prescriptions, community gardening, farmers’ market vouchers). These activities can promote nature contact, strengthen social structures, and improve longer term mental and physical health by activating intrapersonal, interpersonal, and environmental processes. The prescriptions are appropriate for reaching a range of high-risk populations including moms who are minors who are minors, recent immigrants, older adults, economically and linguistically isolated populations, and unlikely users of nature and outdoor spaces.

Summary

More research is needed to understand the impact of SPs on high-risk populations and the supports needed to allow them to feel at ease in the outdoors. Additionally, opportunities exist to develop technologically and socially innovative strategies to track patient participation in social prescriptions, monitor impact over time, and integrate prescribing into standard health care practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The need to belong and to connect with others socially is widely considered to be a fundamental human need [1]. Without a sense of belonging and positive social connections, individuals may experience a sense of deprivation that can lead to loneliness, depression, anxiety, and anger [2,3,4]. Meanwhile, there are scores of studies and scientific reviews that document that the natural environment and ecosystem services it provides can enhance health and well-being, with a particular emphasis on the psychological well-being derived from contact with nature and outdoor activity [5]. This article aims to explore the current evidence for understanding the use of social prescribing (SP) (i.e., non-clinical referral options) as an umbrella social intervention to promote social connectedness and ultimately improve mental, cognitive, and physical health. Moreover, it explores the opportunities to focusing the lens of social prescribing on activities that hold the most promise to activate intrapersonal, interpersonal, and environmental processes that are critical to health and well-being. Finally, it reviews the current literature with an eye towards addressing opportunities to reduce social isolation among populations at risk, including, but not limited to, teenage moms, recent immigrants, older adults, and economically disadvantaged and linguistically isolated populations.

Background

Mental health concerns account for 20% of all primary care consultations [6]. The presence of social risk factors such as social disconnection is so significant that the US-based Institute of Medicine recommends that health providers collect data on patients’ social connections and isolation in addition to overall physical and mental health, education, and lifestyle [7]. Social connection, or lack thereof, is considered a social determinant of health, with well-documented health consequences [8, 9]. These factors are shaped by the environments where we live, work, and play [10] and the inequities that result from how our everyday built environments are designed, developed, and redeveloped. That is, the way we build and organize our cities can foster, complicate, or hinder social connection.

Social connections can be understood through three main dimensions—their functions (e.g., perceived loneliness), their structures (e.g., social isolation), and their qualities (e.g., marital quality) [11]. Loneliness is described as the subjective, unfavorable balance between actual and desired social contacts [12]. That is, loneliness is a painful, unwelcome feeling. People lacking human contact often feel lonely [13]. There is robust evidence that loneliness can compromise physical and psychological health [2, 14]. In recent years, loneliness has been framed as an “epidemic” sweeping across populations in the USA and Europe [15, 16].

Social isolation is within the structural dimension of social connection [17,18,19] that is defined by limited social networks, infrequent social contacts, lack of trusted connections, living alone, and lack of participation in social activities, and is a known risk factor for dementia, depression, cardiovascular disease, and mortality [11, 20,21,22]. Importantly, the effect of social isolation on mortality has been estimated to be equal to or higher than that of other risk factors such as obesity or smoking [9, 23].

In a national survey of health care providers, 85% of respondents opined that unmet basic needs, influenced by social domains, such as access to healthy food, reliable transportation, and adequate housing, are contributing to declining health status for all Americans. Moreover, 80% of respondents reported that social needs of their patients are as important as their medical conditions and that this is particularly true for patients coming from low-income neighborhoods. Finally, providers reported that if they had the option to write prescriptions for social needs, they would include prescriptions for fitness programs, transportation assistance, and healthy food [24•, 25].

Vulnerable Populations

A number of factors may contribute to increased risk for social isolation. Living alone, lack of participation in social groups, having few friends, or strained relationships all are elements of social isolation. Retirement and lack of mobility also increase vulnerability [9]. This includes older military veterans who experience loneliness and social isolation [26]. The number of adults age 65 and older is expected to more than double in the next 25 years—eventually accounting for over 20% of the US and European populations. Given that social isolation among older adults is a predominant health problem, it will likely increase as this segment of the population expands [27]. Therefore, the importance of health-promoting activities and services to address loneliness and social isolation in older populations is increasingly recognized [28].

Immigrants and refugees represent other social groups that often face cultural, social, economic, and linguistic challenges living in a new and unfamiliar place [29]. Scholars attest that loving and close family relationships are a key determinant of positive resettlement outcomes for refugee youth from conflict-prone areas [30]. Yet, migrants’ small, fragile social networks and inadequate informal support structures heighten barriers to accessing social services. More research is needed to understand immigrant and refugee’s specific social support needs and resources [31].

Social connection is a major public health challenge among adolescents as well [3, 32]. The youth from low-income communities encounter greater barriers to forming connections due to frequent moving, substance abuse at home, poverty, and discrimination. Over time, stress accumulates to further amplify poor psychological outcomes [33]. Furthermore, youth from marginalized communities often go without the necessary support to navigate the difficult transition into adulthood and independent living [34]. Developmental changes occurring during the teenage years increase the risk of physical isolation from others and feelings of loneliness [35]. With suicide now the second leading cause of death in American individuals age 10 to 34, the promotion of positive relationships at home, with friends, and in community as a preventive measure is receiving increased attention [36].

Social Prescribing as a Path Towards Addressing Community Social Needs

What Is Social Prescribing?

The practice of social prescribing provides physicians, nurses, social workers, and other licensed professionals with non-medical referral options (e.g., housing subsidies, food vouchers to attend farmers’ markets, community arts activities, walking clubs, cycling, communal gardening) that work in concert with existing treatments to support connectedness and by extension, mental well-being, health behaviors, and physical health [37, 38]. The use of social prescriptions, also referred to as “connection prescriptions” [22] or “community referrals,” links screening programs with social action and should involve not only health care providers but also third sector organizations such as local non-profit organizations, local municipalities (e.g., social services and schools), recreational facilities, neighborhood organizations, and affected populations. Such partnerships represent a holistic strategy for confronting persistent health inequities, addressing unmet psychosocial needs, and reducing health care office visits [38,39,40,41].

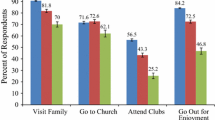

In Fig. 1, we visualize the concept of “social prescribing” (SP) through a broad lens that envisions socially oriented nature-based interventions to foster and sustain social connections and consequently reduce the risk of social isolation and loneliness and promote health and well-being. SP is a structured therapeutic intervention that targets psychological processes and requires direct participation in everyday environments in order to activate the processes that support social connection and promote and sustain pro-health behaviors (e.g., physical activity and nutrition) and well-being [42,43,44,45].

The research described in this review covers the theoretical basis and empirical evidence for establishing a green-outdoors bent to social prescribing, which includes reviews of park prescription programs [46], group hiking prescriptions [47], farmers’ market prescriptions [48], “Walk with a Doc” programs (https://walkwithadoc.org/), and exercise referral programs [49,50,51]. These social prescriptions take various forms, such as referrals for high-risk patients to weekly, biweekly, or monthly guided outdoor activities with provided transportation [44••, 47], or open-ended, digitally supported prescriptions outlining expected duration, intensity, and frequency of outdoor physical activity [24•].

The applications of SP are diverse and can be used to benefit any condition that might be improved through behavior change, increasing activity, and increasing connectedness—all three being related. SPs in the European context have been aimed at obesity and diabetes, addiction, literacy, and compliance with treatment. In Barcelona, for example, social prescriptions have been used in primary health care centers in the metropolitan area of Barcelona. This program found significant improvements in emotional well-being and social support among patients (N = 85), mainly women participating in a pre-post pilot study [52]. SP has proved to be useful in helping patients but also those that hyper-use (more than 12 visits per year) primary care services [42, 53,54,55,56]. Early studies of these programs demonstrate that patients following SP show improved self-esteem, self-efficacy, and confidence and mood [37, 52, 57,58,59,60,61].

Adding a Nature-Based Emphasis to Social Prescribing

Over the past decade, the evidence suggesting that nature contact is good for various aspects of physical and mental health has grown substantially [62]. Consequently, an increasing number of US health insurance companies are beginning to invest in nature-based prescriptions as a way to promote time outdoors and time being physically active. For example, Kaiser Permanente partnered with the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy to fund health-focused park programs and park prescriptions [63]. Additionally, Blue Cross Blue Shield incentivizes North Carolina clinics for participating in Track Rx, a program to help families learn how spending time in nature improves their overall health and well-being. Recreational Equipment, Inc. (REI), a leading US outdoor recreation retailer, recently invested $1 million in the University of Washington’s EarthLab that studies the connection between human health and time spent outdoors (https://www.rei.com/blog/news/a-dose-of-the-outdoors), with a particular interest in how to operationalize prescriptions programs in low-income areas and to use this evidence to influence national policymakers, decision-makers, and local and regional leaders in advancing programs and policies that support nature-based connections.

The primary avenue in the literature connecting nature to improved mental and physical health is through nature’s restorative and stress-reducing qualities [64, 65]. However, the social connectedness experienced while spending time outdoors with others is increasingly being explored as another avenue to reduce stress and encourage children’s cognitive development [66,67,68]. While there are a several published evaluations of nature-based prescriptions, the scholarship around evaluating nature-based interventions and social connection is limited. However, there are a number of relevant programs that we draw upon on to better understand how the mechanisms that inform how nature-based therapeutic prescriptions can function under the broader umbrella of social prescribing.

Approach

We conducted a literature review using key search terms to identify published studies that evaluated prescription-based interventions to address health issues such as physical inactivity, poor nutrition, stress, or social processes such as social connection. We considered interventions that fit within our broader lens of nature-based social prescriptions that included a clinical referral to outdoor activity. Search terms included “social prescriptions,” “social prescribing,” “community referrals,” “nature prescription,” “connections prescription,” “walking prescriptions,” “park prescription,” “nature-based,” “social connectedness,” “green exercise,” “physical activity counseling,” and “outdoor prescriptions.” Selected articles included a prescription element, were tied to clinical care, and integrated proximal outcomes that were rooted in social connection or social connectedness in and of itself. The literature review informed our proposed model (see Fig. 1), which suggests that nature-based social prescription increases social connectedness and influences physical health and mental well-being by certain intrapersonal, interpersonal, and environmental pathways.

Nature-Based Social Prescription Targets Proximal Intrapersonal, Interpersonal, and Environmental Processes to Motivate Lasting Change

There is debate surrounding the mechanisms by which nature promotes therapeutic experiences [62]. These studies, although limited by small sample sizes and few experimental studies, suggest that nature can be beneficial in promoting recovery from stress and fatigue [69]. Ulrich’s Stress Reduction Theory (SRT) hypothesizes that environmental features induce subconscious affective reactions which support psychophysiological stress recovery. Landscape features such as vegetation and water inspire positive emotions and reduce negative thoughts, while maintaining non-vigilant attention [70]. The Kaplans [71] argue through the Attention Restoration Theory (ART) that nature has the capacity to renew attention and promotes wellness via reduced mental fatigue. In keeping with ART, a person can focus with “effortless attention” upon “soft fascinations” easily found in the natural world, such as leaves moving in the breeze. Scholars have argued through the theory of Biophilia [72], people possess an innate tendency to focus on life and lifelike processes and to respond with emotional intensity to the natural world. Wilson describes how humans are drawn to nature-like patterns and stimuli and lifelike processes because of a primary exposure to nature during human evolution. He argues that there has been little genetic adaptation recently to modern, urban environments [73].

These leading theories have engendered an extensive body of evidence that exposure to the natural world may have a significantly positive impact on human health and well-being. The model presented in this paper builds on the evidence of how nature-based interventions impact population health, by exploring the role of social connection in the outdoors. Little is known about the effects of social connection in the outdoors as another possible mechanism underlying the positive relationship between wellness and nature [74]. It is unclear if and how mental fatigue (ART), stress (SRT), or emotional engagement with nature (biophilia) may be impacted by social connections in natural settings and consequently influence health and mental well-being, as few studies have explored these potential mechanisms. However, research has shown that connecting with others in nature can break down barriers between community members [69], increase feelings of connectedness with others [75], and reduce stress [44••].

Understanding the theory supporting behavioral interventions can help us understand what empowers individuals to make healthy decisions [76]. Relevant studies from our literature review are included in Table 1, which describes the intervention, the primary outcomes, and the social and psychological processes that are theorized to influence pro-social, pro-health, and pro-environmental behavioral outcomes. Intrapersonal processes that give way to social connections and longer term outcomes included factors such as participation in an activity (competence), sense of belonging, sense of enjoyment, sense of purpose, and sense of awe. Interpersonal processes included social involvement, relatedness, and shared learning. Environmental processes included access to nature, perceived neighborhood attachment, and perceived aesthetics.

Intrapersonal Processes

Participating in outdoor activities and being in proximity to nature can influence internal processes such as autonomy, competence, sense of belonging, sense of purpose, and sense of awe among others. These relationships can be understood through the lens of self-determination theory, which poses that the driving force behind behavior change comes from within an individual. The theory asserts that an individual’s self-regulation relies on both intrinsic motivation and well-internalized extrinsic motivation [81]. According to self-determination theory, for optimal growth and function, three universal psychological needs must be met: the principles of autonomy, perceived competence, and relatedness to others [82].

Building on these processes, exercise referral schemes represent a referral model in primary care settings to promote physical activity and reduce sedentary time. Usually participants are directed to sports centers or leisure facilities for exercise programs. The effects are often short-lived [51]. However, the use of social prescribing with enhanced self-management strategies (e.g., individual goal setting, self-monitoring, prompts and cues) have the potential to strengthen the impact of such measures in fostering physical activity behavior change, and in turn, affect mood and feelings of connection if the activities are done within a group context [49, 50]. Moreover, these strategies can be linked with nature-based solutions, promoting access to social and natural settings and open spaces [83].

Farmers’ markets offer another type of outdoor environment that represents a social, civic place that is often located in parks or public plazas and connects people to urban agriculture and fresh, locally produced food. In one study, Trapl and others introduced a produce prescription program for pregnant women in underserved areas with limited access to fresh produce [48]. Health care providers offered nutritional counseling and $40 farmers market vouchers to participants at monthly prenatal visits. Fifty-six percent of study participants redeemed at least one farmer’s market, and 95% of participants found the program materials to be relevant and useful. This strategy to incentivize fruit and vegetable consumption through a prescription empowers women in this study to engage in healthy behaviors by tapping into psychosocial processes such as autonomy, competence, and belonging among others. Moreover, it connects women and their families to an interactional space in their respective communities.

Looking to other intrapersonal pathways illustrated in the literature, Taylor and Kuo examined nature’s effect on concentration by guiding children professionally diagnosed with ADHD on 20-min walks in natural and urban settings [80]. After each walk, concentration was measured using Digit Span Backwards. Participants concentrated better after a walk in an urban park than after a downtown or neighborhood walk. Effect sizes were substantial and similar to those reported for drug prescription for ADHD.

Building upon this evidence, Anderson and others [77] explored the impact of emotional experiences in the outdoors on well-being by analyzing how the awe experienced during whitewater rafting trips predicted greater improvements in well-being and stress-related symptoms than the effects of other positive emotions such as joy, contentment, and gratitude. To test this, researchers developed 1- to 4-day whitewater rafting prescription for veterans and youth from underserved communities. Participants completed a daily rafting diary detailing the emotions, cognitions, and social interactions they experienced. The study found that the rafting trips produced substantial and significant improvements in overall well-being and feelings of awe [77]. Research by Zhang and others [84] found a moderator effect of engagement with beauty in nature on the relationship between connectedness to nature and life satisfaction and self-esteem. These cases highlight how emotion and sensations inspired by natural surroundings might be a mechanism of how nature improves health and well-being.

Community gardens have the potential to ignite psychosocial processes and, in turn, influence health behaviors and mental and physical health. They are understood as social green spaces where people from more than one family garden communally or side by side [76]. Qualitative research with community gardeners illustrates that reasons people garden are largely driven by intrinsic motivations and sensory experiences to feel good, to put ones’ hands in the earth, and to learn a new skill, consequently not simply to improve their physical health [43] and align with the biophilia hypothesis described above [72]. This has practical implications for providers prescribing nature activities in order to reduce stress and motivate physical activity and social interactions with others. Clients experiencing competence and autonomy as well as a sense of enjoyment, awe, purpose, and belonging may be inspired to commit to nature-based therapeutic services and therefore are more likely to experience a boost in mood that providers can build upon to address other therapeutic goals [79].

Interpersonal Processes

Moving beyond nature’s cognitively and mentally restorative qualities, outdoor experiences can facilitate dynamic processes of social or interpersonal interactions [66]. Positive social interactions among adults have been shown to lead to better health and longevity when compared with more isolated peers [85]. Studies of older adults found that enjoying leisure activities with friends, spouses, and family played a significant role in the older adults’ degree of participation, and leisure activities made up a notable portion of their social worlds [86]. In addition, small regular group meetings with an education focus and groups where participants participate actively were among the most effective interventions in the literature at reducing social isolation and loneliness [21, 87] and in longer term chronic conditions such as diabetes [88].

Yet, what role does nature play in facilitating social interaction? Recent studies suggest that outdoor experiences may facilitate social involvement and shared learning. Izenstark and Ebata invited mother and daughter dyads to walk through a natural area and a shopping mall for 20 min each [78••]. Results showed that the nature walk was perceived as more fun, interesting, and relaxing, and it contributed to greater cohesion between mother and daughter. The study highlights the importance of exposure to nature in families’ everyday lives and strengthens the case that active outdoor leisure activity experiences can influence and fortify family bonds [89].

Returning to the theme of community gardens, these settings represent examples of specific outdoor environments that amplify social cohesion, support networking, relatedness, and increase levels of social capital by providing a cohesive “third space” for gardeners to congregate [90, 91]. Community gardening brings residents together in the sharing of seeds, tools, recipes, and produce [92]. Furthermore, these spaces create opportunities for people to meet and interact with others through the organization of group work days and social events, volunteering, conversation, gathering, and learning with others [93, 94]. These social interactions are key to promoting neighbor-to-neighbor connections, collective efficacy, and one’s sense of place within communities [43].

Being exposed to nature is hypothesized to decrease feelings of loneliness by helping to build relationships that can reduce stress [95]. In a pioneering randomized trial with low-income families exploring the impact of physician counseling about nature with or without facilitated group outings, Razani and others discovered that 3 months following the Stay Healthy In Nature Everyday (SHINE) parks prescription, participants’ feelings of loneliness decreased by 1.03 points on a 9-point scale, and stress reduced significantly [44••]. This supports the suggestion that frequent, daily contact with nature may be most effective in reducing stress [96], as increases in weekly park visits were associated with incremental decreases in stress [44••].

Perceived Environment

The design of our built environment and the areas where people live, work, and play are directly related to the amount of time people spend outdoors [97]. The layout of our communities, transportation infrastructure, and access to parks and trails generate either obstacles or opportunities for people to interact with nature [98]. Our model (Fig. 1) illustrates how access to nearby nature and outdoor resources are critical for health and well-being. These attributes can include presence or absence of parks [99], gardens [100], or farmers markets [48], and also involve how people feel when experiencing these places, and what impact living near them can have on mental and physical health and well-being.

The ways in which people perceive their environment may involve the bonds people have with these places, also known as place attachment or a broader sense of beauty, e.g., aesthetics. Neighborhood attachment, one facet of place attachment, relates to an emotional bond to one’s neighborhood that may influence access to and use of everyday places [101]. The bonds may be key to explaining how the built and natural environment influence behavior and longer term health outcomes [102,103,104].

One’s perception of the form of the surrounding built environment is shaped, in part, by landscape experiences, such as aesthetics [43, 105,106,107]. Environmental aesthetics can be understood as the study of appreciation of the environment, how this appreciation changes as people interact with the environment, and how these experiences guide future aesthetic interactions [108].

Yet, how do aesthetic experiences relate to physical health? According to Bronfenbrenner, human development is influenced by the larger environmental milieu [109]. With this understanding, community gardens represent a strong example of how human development occurs in the social context beyond individuals. Gardeners express positive feelings of pride and joy in relation to their gardens [71]. Gardens provide opportunities for multisensory experiences while digging in the soil, harvesting produce, and experiencing quietude and birdsong. Gardeners express enthusiasm over how their vegetables taste and the confidence that they gain from socializing with other gardeners. Sharing personal histories with others, working in partnership to create beauty for others, and physically slowing down and mindfully appreciating fresh air, and horticultural beauty contribute to psychosocial well-being [43]. Research with community gardeners found that these kinds of aesthetic experiences generate meaning for gardeners, which may lead to positive health outcomes such as reduced stress, depression, and social isolation [90, 110].

In an example illustrating how environmental processes can be encouraged in nature-based social prescriptions, Passmore and Holder [79] instructed undergraduate students to photograph and reflect upon their natural and built surroundings for two-weeks. Participants paid attention to how nearby, everyday nature made them feel, photographed the landscapes and objects that evoked emotion, and described the emotions that arose. Researchers found that increased attention to everyday nature in this case significantly increased overall sense of connectedness and pro-social orientation. Importantly, the significant effects of noticing nature on well-being did not depend upon the trait levels of connectedness to nature or engagement with beauty that was already characteristic of each individual participant.

Future Directions

Nature-based social prescriptions offer health care providers with a valuable opportunity to help adults and children find ways to feel more socially connected and be part of their larger community and natural environment. The developing practice represents a low-cost, creative intervention to strengthen social networks, reduce stress, and facilitate social connectedness among participants and providers without requiring expensive gym memberships or special clothing to access a local park or natural area with friends, family, or groups. These prescriptions fill the need to focus on interventions that harness nature’s beneficial impacts and bestow a powerful effect on population health. By aligning clinicians and social workers with community members, we can move closer to creating socially connected and physically active communities.

A next critical next step is to adopt social isolation and loneliness screening measures for health centers to gauge the extensive of these conditions. Along with standardized screening approaches, research is needed to co-create prescriptions that are reasonable for those who prescribe them and meaningful for the people who need them. Refreshing clinical preventive health care can buoy provider spirits to generate solutions for low-income, isolated, and hard-to-reach individuals [47].

In addition, more research is needed to understand non-dominant communities’ access to and connection with natural areas, including, but not limited to, minority and low-income populations and recent immigrants. It is clear that all sociocultural groups do not share the same relationship to the outdoors. For example, there is a general tendency for White recreationists to travel farther and more frequently to wildland parks and natural areas than African Americans [111]. Identifying how, when, and why different groups interact with nature will ensure that future studies follow equitable, community-based research practices. For too long, the histories, experiences, and cultural knowledge of the outdoors in communities of color have been devalued or omitted from environmental education and advocacy narratives [112]. In lieu of merely writing a prescription for outdoor activity, individuals without a childhood connection to nature may need additional support and programming for them to feel at ease in the outdoors [113].

Providers currently do not have a reliable mechanism for recording patient behavior or connecting individuals to outdoor amenities. Social prescription software may solve this in the future. Such software will help providers easily identify nearby natural resources, such as parks and gardens, that fit the interests, aptitudes, and schedules of patients and their families. Furthermore, using location services via cellular data can help monitor uptake and completion of the social prescription. As nature-based social prescribing programs expand and develop nationwide, technological innovation through digital applications may assist with the adoption and integration of prescribing into everyday medical care.

There is an emerging evidence base suggesting that nature-based social prescribing and other related referral schemes providing promising avenues to promote social connection as an antidote to social isolation and loneliness. However, the field could benefit from more quantitative investigations that employ experimental study designs [38, 46, 77, 114] with larger sample sizes [24•], use valid and reliable outcome measures, include control groups, and use inferential statistics [38]. Moreover, there is a need to evaluate the range of interventions across different demographic and social groups to understand the uptake of the intervention by high-risk populations [115]. Investing in robust pragmatic research and evaluation will move the SP field forward by strengthening the evidence base for affordable, sustainable, and scalable interventions that can counter mounting environmental stressors, housing and job insecurities and safety by promoting social connection and over the longer term, mental well-being and population health.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Esfahani-Smith E. The power of meaning: crafting a life that matters. New York: Crown Publishing; 2017.

Baumeister R, Leary M. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull. 1995;117(3):497–529.

Heinrich LM, Gullone E. The clinical significance of loneliness: a literature review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(6):695–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002.

Berkman L, Glass T. Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. In: Berkman L, Kawachi I, editors. Social epidemiology. 1st ed. New York, New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. p. 391.

Aerts R, Honnay O, Van Nieuwenhuyse A. Biodiversity and human health: mechanisms and evidence of the positive health effects of diversity in nature and green spaces. Br Med Bull. 2018;127(1):5–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldy021.

Kilgarriff-Foster A, O’Cathain A. Exploring the components and impact of social prescribing. J Public Ment Health. 2015;14(3):127–34.

Institute of Medicine. Behavioral domains in electronic health records, phase 1. Washington DC2014.

Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1099–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6.

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith T, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352.

Srinivasan S, O’Fallon LR, Dearry A. Creating healthy communities, healthy homes, healthy people: initiating a research agenda on the built environment and public health. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(9):1446–50.

Holt-Lunstad J, Robles T, Sbarra D. Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. The American psychologist. 2017;72(6):517–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000103.

Tomaka J, Thompson S, Palacios R. The relation of social isolation, loneliness, and social support to disease outcomes among the elderly. Journal of aging and health. 2006;18(3):359–84.

Yildirim Y, Kocabiyik S. The relationship between social support and loneliness in Turkish patients with cancer. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(5–6):832–9.

MacDonald G, Leary M. Why does social exclusion hurt? The relationship between social and physical pain. Psychol Bull. 2005;131:202–23.

Khullar D. How social isolation is killing us. New York Times 2016.

American Psychological Association. Social isolation, loneliness could be greater threat to public health than obesity. In: ScienceDaily. 2017. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/08/170805165319.htm.

Cornwell EY, Waite LJ. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2009;50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650905000103.

Coyle CE, Dugan E. Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. J Aging Health. 2012;24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264312460275.

Tanskanen J, Anttila T. A prospective study of social isolation, loneliness, and mortality in Finland. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(11):2042–8. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303431.

Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40(2):218–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8.

Cattan M, Kime N, Bagnall A-M. The use of telephone befriending in low level support for socially isolated older people – an evaluation. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2011;19(2):198–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00967.x.

Martino J, Pegg J, Frates EP. The connection prescription: using the power of social interactions and the deep desire for connectedness to empower health and wellness. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2015;11(6):466–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827615608788.

Tilvis RS, Laitala V, Routasalo PE, Pitkälä KH. Suffering from loneliness indicates significant mortality risk of older people. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:534781. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/534781.

• Zarr R, Cottrell L, Merrill C. Park prescription (DC Park Rx): a new strategy to combat chronic disease in children. J Phys Activity Health. 2017;14(1):1–2. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2017-0021This article outlines a feasibility study of DC Park Rx, an open-ended, digitally supported park prescription outlining expected duration, intensity, and frequency of outdoor physical activity. DC Park Rx, now Park Rx America, was one of the first park prescription applications, with health care providers in 16 states now using it.

Fenton. Health care’s blind side. The overlooked connection between social needs and good health. 2011.

Wilson G, Hill M, Kiernan M. Loneliness and social isolation of military veterans: systematic narrative review. Occup Med. 2018;68(9):600–9.

Nicholson NR. A review of social isolation: an important but underassessed condition in older adults. J Primary Prevent. 2012;33(137). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-012-0271-2.

Cattan M, White M, Bond J, Learmouth A. Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: a systematic review of health promotion interventions. Ageing Soc. 2005;25(1):41–67.

Hordyk SR, Hanley J, Richard É. “Nature is there; its free”: urban greenspace and the social determinants of health of immigrant families. Health & Place. 2015;34:74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.03.016.

McMichael C, Gifford SM, Correa-Velez I. Negotiating family, navigating resettlement: family connectedness amongst resettled youth with refugee backgrounds living in Melbourne, Australia. J Youth Stud. 2011;14(2):179–95.

Stewart M, Anderson J, Beiser M, Mwakarimba E, Neufeld A, Simich L, et al. Multicultural meanings of social support among immigrants and refugees. Int Migr. 2008;46(3):123–59.

Spithoven AW, Bastin M, Bijttebier P, Goossens L. Lonely adolescents and their best friend: an examination of loneliness and friendship quality in best friendship dyads. J Child Fam Stud. 2018;27(11):3598–605.

Bluth K, Roberson PN, Gaylord SA, Faurot KR, Grewen KM, Arzon S, et al. Does self-compassion protect adolescents from stress? J Child Fam Stud. 2016;25(4):1098–109.

Eva AL, Thayer NM. Learning to BREATHE: a pilot study of a mindfulness-based intervention to support marginalized youth. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine. 2017;22(4):580–91.

Laursen B, Hartl AC. Understanding loneliness during adolescence: developmental changes that increase the risk of perceived social isolation. J Adolesc. 2013;36(6):1261–8.

National Institute of Mental Health. Suicide fact sheet. National Institute of Mental Health, Washington, DC. 2019. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide.shtml. Accessed May 7 2019.

Bickerdike L, Booth A, Wilson PM, Farley K, Wright K. Social prescribing: less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Open. 2017;7(4).

Chatterjee HJ, Camic PM, Lockyer B, Thomson LJM. Non-clinical community interventions: a systematised review of social prescribing schemes. Arts Health. 2018;10(2):97–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/17533015.2017.1334002.

Cawston P. Social prescribing in very deprived areas. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61(586):350.

Husk K, Blockley K, Lovell R, Bethel A, Bloomfield D, Warber S, et al. What approaches to social prescribing work, for whom, and in what circumstances? A protocol for a realist review. Systematic Rev. 2016;5:93–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0269-6.

Kimberlee R, Jones M, Powell J. Measuring the economic impact of the wellspring healthy living centre’s social prescribing wellbeing programme for low level mental health issues encountered by GP services. Proving our Value. 2013.

Barton J, Griffin M, Pretty J. Exercise-, nature- and socially interactive-based initiatives improve mood and self-esteem in the clinical population. Perspectives in Public Health. 2011;132(2):89–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913910393862.

Hale J, Knapp C, Bardwell L, Buchenau M, Marshall J, Sancar F, et al. Connecting food environments and health through the relational nature of aesthetics: gaining insight through the community gardening experience. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:1853–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.044.

•• Razani N, Morshed S, Kohn MA, Wells NM, Thompson D, Alqassari M, et al. Effect of park prescriptions with and without group visits to parks on stress reduction in low-income parents: SHINE randomized trial. PloS one. 2018;13(2):e0192921 This paper reviews a first of its kind randomized trial of a park prescription, through a program called SHINE (Staying Healthy in Nature Everyday). The study compares the effect of a physician’s counseling about nature with or without facilitated group outings on stress and other outcomes among low-income parents.

Walton GM. The new science of wise psychological interventions. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2014;23(1):73–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721413512856.

Razani N, Kohn MA, Wells NM, Thompson D, Hamilton Flores H, Rutherford GW. Design and evaluation of a park prescription program for stress reduction and health promotion in low-income families: the Stay Healthy in Nature Everyday (SHINE) study protocol. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2016;51:8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2016.09.007.

James AK, Hess P, Perkins ME, Taveras EM, Scirica CS. Prescribing outdoor play: outdoors Rx. Clin Pediatr. 2017;56(6):519–24.

Trapl ES, Joshi K, Taggart M, Patrick A, Meschkat E, Freedman DA. Mixed methods evaluation of a produce prescription program for pregnant women. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 2017;12(4):529–43.

Coll-Planas L, Blancafort Alias S, Tully M, Caserotti P, Giné-Garriga M, Blackburn N, et al. Exercise referral schemes enhanced by self-management strategies to reduce sedentary behaviour and increase physical activity among community-dwelling older adults from four European countries: protocol for the process evaluation of the SITLESS randomised controlled trial. BMJ open. 2019;9(6):e027073-e. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027073.

Giné-Garriga M, Coll-Planas L, Guerra M, Domingo À, Roqué M, Caserotti P, et al. The SITLESS project: exercise referral schemes enhanced by self-management strategies to battle sedentary behaviour in older adults: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):221. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-017-1956-x.

Giné-Garriga M, Roqué-Fíguls M, Coll-Planas L, Sitjà-Rabert M, Salvà A. Physical exercise interventions for improving performance-based measures of physical function in community-dwelling, frail older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(4):753–69.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2013.11.007.

Capella-González J, Braddick F, Fields H, Garcia L, Farran J. Los retos de la prescripción social en la Atención Primaria de Catalunya: la percepción de los profesionales. Publicacion Periodica del Programa de Actividades Comunitarias en Atencion Primaria. 2016;18(2):7.

Verghese J, Lipton RB, Katz MJ, Hall CB, Derby CA, Kuslansky G, et al. Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(25):2508–16. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa022252.

Friedli L, Watson S. Social prescribing for mental health. Durham: Northern Centre for Mental Health; 2004.

Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth), University of Melbourne. Promoting mental health: concepts, emerging evidence, practice: a summary report. Genève: World Health Organization; 2004.

Pascucci M. The revival of placemaking. Creative Nursing. 2015;21(4):200–5.

Mason MCK editor. Ciudades Saludables: El Impacto de Urbanismo en la Salud Publica. Conference of the Yachay Institute, Marte Democratico el Congreso de Peru, Lima; 2016; Peru.

Plough AL. Building a culture of health: a critical role for public health services and systems research. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(Suppl 2):S150–S2. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302410.

Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202.

Wardian J, Robbins D, Wolfersteig W, Johnson T, Dustman P. Validation of the DSSI-10 to measure social support in a general population. Res Soc Work Pract. 2013;23(1):100–6.

Grellier J, White MP, Albin M, Bell S, Elliott LR, Gascón M, et al. BlueHealth: a study programme protocol for mapping and quantifying the potential benefits to public health and well-being from Europe’s blue spaces. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e016188.

Hartig T, Mitchell R, DeVries S, Frumkin H. Nature and health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:207–28.

Institute at the Golden Gate. A program of the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy. San Francisco, CA. 2018. https://instituteatgoldengate.org/programs/health. Accessed 06/08/19 2019.

Kaplan S. The restorative benefits of nature: toward an integrative framework. J Environ Psychol. 1995;15. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2.

Ulrich RS. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science. 1984;224(4647):420. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6143402.

Seltenrich N. Just what the doctor ordered: using parks to improve children’s health. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123(10):A254–A9. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.123-A254.

Chawla L, Keena K, Pevec I, Stanley E. Green schoolyards as havens from stress and resources for resilience in childhood and adolescence. Health Place. 2014;28:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.03.001.

Chawla L. Benefits of nature contact for children. J Plan Lit. 2015;30(4):433–52.

Maas J, van Dillen SME, Verheji RA, Groenewegen PP. Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relation between green space and health. Health Place. 2009;15:586–95.

Ulrich RS, Simons RF, Losito BD, Fiorito E, Miles MA, Zelson M. Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J Environ Psychol. 1991;11(3):201–30.

Kaplan R, Kaplan S. The experience of nature: a psychological perspective. New York: Cambridge Press; 1989.

Wilson E. Biophilia, the human bond with other species. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press; 1984.

Kellert SR, Wilson EO. The biophilia hypothesis. Washington, D.C: Island Press; 1995.

Cartwright BDS, White MP, Clitherow TJ. Nearby nature ‘buffers’ the effect of low social connectedness on adult subjective wellbeing over the last 7 days. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(6):1238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061238.

Weinstein N, Przybylski AK, Ryan RM. Can nature make us more caring? Effects of immersion in nature on intrinsic aspirations and generosity. Personal Soc Psychol Bull. 2009;35(10):1315–29.

Alaimo K, Beavers AW, Crawford C, Snyder EH, Litt JS. Amplifying health through community gardens: a framework for advancing multicomponent, behaviorally based neighborhood interventions. Current Environmental Health Reports. 2016;3(3):302–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-016-0105-0.

Anderson CL, Monroy M, Keltner D. Awe in nature heals: evidence from military veterans, at-risk youth, and college students. Emotion. 2018;18(8):1195–202. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000442.

•• Izenstark D, Ebata A. The effects of the natural environment on attention and family cohesion: an experimental study. Children, Youth and Environments. 2017;27(2):93–109 This study’s results from mother-daughter dyads walking through a shopping mall and a natural setting show that the nature walk was perceived as more fun, interesting, and relaxing, and it contributed to greater cohesion between mother and daughter. The study highlights the importance of exposure to nature in families’ everyday lives and strengthens the case that active outdoor leisure activity experiences can influence and fortify social bonds.

Passmore H-A, Holder MD. Noticing nature: individual and social benefits of a two-week intervention. J Posit Psychol. 2017;12(6):537–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1221126.

Faber Taylor A, Kuo FE. Children with attention deficits concentrate better after walk in the park. J Atten Disord. 2009;12(5):402–9.

Deci EL, Ryan RM. Self-determination theory in health care and its relations to motivational interviewing: a few comments. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-9-24.

Patrick H, Williams G. Self-determination theory: its application to health behavior and complementarity with motivational interviewing. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9(18):1–12.

Pretty J, Peacock J, Hine R, Sellens M, South N, Griffin M. Green exercise in the UK countryside: effects on health and psychological well-being, and implications for policy and planning. J Environ Plan Manag. 2007;50(2):211–31.

Zhang JW, Howell RT, Iyer R. Engagement with natural beauty moderates the positive relation between connectedness with nature and psychological well-being. J Environ Psychol. 2014;38:55–63.

Umberson D, Karas MJ. Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(1_suppl):S54–66.

Toepoel V. Ageing, leisure, and social connectedness: how could leisure help reduce social isolation of older people? Soc Indic Res. 2013;113(1):355–72.

Dickens AP, Richards SH, Greaves CJ, Campbell JL. Interventions targeting social isolation in older people: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):647.

The Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(12):2165–71.

Orthner DK, Mancini JA. Leisure impacts on family interaction and cohesion. J Leis Res. 1990;22(2):125–37.

Litt JS, Schmiege SJ, Hale JW, Buchenau M, Sancar F. Exploring ecological, emotional and social levers of self-rated health for urban gardeners and non-gardeners: a path analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2015;144(November):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.09.004.

Firth C, Maye D, Pearson D. Developing “community” in community gardens. Local Environ. 2011;16(6):555–68.

Okvat HA, Zautra AJ. Community gardening: a parsimonious path to individual, community, and environmental resilience. Am J Community Psychol. 2011;47(3–4):374–87.

Teig E, Amulya J, Buchenau M, Bardwell L, Marshall J, Litt JS. Collective efficacy in Denver, Colorado: strengthening neighborhoods and health through community gardens. Health Place. 2009;15:1115–22.

Petit-Boix A, Apul D. From cascade to bottom-up ecosystem services model: how does social cohesion emerge from urban agriculture? Sustainability. 2018;10(4):998.

de Vries S, van Dillen SME, Groenewegen PP, Spreeuwenberg P. Streetscape greenery and health: stress, social cohesion and physical activity as mediators. Soc Sci Med 2013;94(0):26–33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.030.

Ekkel ED, de Vries S. Nearby green space and human health: evaluating accessibility metrics. Landsc Urban Plan. 2017;157:214–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.06.008.

Sallis JF, Floyd MF, Rodríguez DA, Saelens BE. Role of built environments in physical activity, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2012;125(5):729–37. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.110.969022.

Wessel LA. Shifting gears: engaging nurse practitioners in prescribing time outdoors. J Nurse Pract. 2017;13(1):89–96.

Pretty J. How nature contributes to mental and physical health. Spiritual Health Int. 2004;5(2):68–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/shi.220.

Clatworthy J, Hinds J, M. Camic P. Gardening as a mental health intervention: a review. Ment Health Rev J 2013;18(4):214–225.

Cattell V, Dines N, Gesler W, Curtis S. Mingling, observing, and lingering: everyday public spaces and their implications for well-being and social relations. Health & Place. 2008;14(3):544–61.

Comstock N, Dickinson M, Marshall JA, Soobader MJ, Turbin MS, Buchenau M, et al. Neighborhood attachment and its correlates: exploring neighborhood conditions, collective efficacy and gardening. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2010;30:435–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.05.001.

Lenzi M, Vieno A, Perkins D, Pastore M, Santinello M, Mazzardis S. Perceived neighborhood social resources as determinants of prosocial behavior in early adolescence. Am J Community Psychol. 2011:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-011-9470-x.

Kafetsios K, Sideridis GD. Attachment, social support and well-being in young and older adults. J Health Psychol. 2006;11(6):863–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105306069084.

Jorgensen A. Beyond the view: future directions in landscape aesthetics research. Landsc Urban Plan. 2011;100(4):353–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.02.023.

Henderson H, Child S, Moore S, Moore JB, Kaczynski AT. The influence of neighborhood aesthetics, safety, and social cohesion on perceived stress in disadvantaged communities. Am J Community Psychol. 2016;58(1–2):80–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12081.

Root ED, Silbernagel K, Litt JS. Unpacking healthy landscapes: empirical assessment of neighborhood aesthetic ratings in an urban setting. Landsc Urban Plan. 2017;168:38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.09.028.

Carlson A. Environmental aesthetics. 1998. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780415249126-M047-1.

Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979.

Litt JS, Soobader M, Turbin MS, Hale J, Buchenau M, Marshall JA. The influences of social involvement, neighborhood aesthetics and community garden participation on fruit and vegetable consumption. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:1466–73.

Gobster P. Managing urban parks for a racially and ethnically diverse clientele. Leis Sci. 2002;24:143–59.

Rose J, Paisley K. White privilege in experiential education: a critical reflection. Leis Sci. 2012;34(2):136–54.

Asah ST, Bengston DN, Westphal LM. The influence of childhood: operational pathways to adulthood participation in nature-based activities. Environ Behav. 2012;44(4):545–69.

Husk K, Blockley K, Lovell R, Bethel A, Lang I, Byng R, et al. What approaches to social prescribing work, for whom, and in what circumstances? A realist review. Health Soc Care Commun. 2019;0(0). https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12839.

Drinkwater C, Wildman J, Moffatt S. Social prescribing. BMJ. 2019;364:l1285. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l1285.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Built Environment and Health

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leavell, M.A., Leiferman, J.A., Gascon, M. et al. Nature-Based Social Prescribing in Urban Settings to Improve Social Connectedness and Mental Well-being: a Review. Curr Envir Health Rpt 6, 297–308 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-019-00251-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-019-00251-7