Abstract

Digital well-being has become a popular theme within a public discourse that increasingly attracts consumers, businesses, government institutions and technology providers who all face challenges in their technology-driven existence. However, there have been no attempts to create a comprehensive framework for a general understanding of digital well-being and the new roles and responsibilities that emerge from it in the tourism domain. Thus, this paper looks at understanding digital well-being in general and its concomitant applications in the tourism domain. After mapping characteristic digital well-being approaches and examples, we foresee the need for establishing a digital well-being continuum between everyday life and tourism that rests on three new sets of roles and responsibilities for the tourism domain, grouped around the need for adopting digital well-being philosophy in tourism, setting up new policies, and designing novel services and experiences.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Digital well-being emerged as a concept from rising public concerns regarding technostress and the effects of information and communication technologies (ITC) over-use on individual mental and physical health and on auxiliary aspects of life, including effects on society and the environment. In simple terms, digital well-being can be seen as a state of personal well-being experienced through the healthy and responsible use of digital technology (Marsden 2020). However, other existing definitions are more context-specific. According to the EIT (European Institute of Innovation and Technology 2018), digital well-being is defined as safeguarding health for youth, working professionals, and the elderly, by analyzing sensor data. Another pragmatic definition emphasizes that digital well-being should include paying attention to the impact technology has on mental or physical health and knowing how to cope with difficult experiences (Irish Internet Safety Awareness Centre 2019). Google defines it as relating to the development of tools that improve life, rather than distract from it (Google 2021).

Undoubtedly, digital well-being, as a general term, has much meaning, both for persons that should be able to experience it and for the entities involved in digital well-being provision. Thus, according to one of the often-cited formulations of digital well-being, it is a framework that looks after personal health, safety, relationships and work-life balance in digital settings (Beetham 2016). According to the same author, digital well-being is achieved by enabling safe and responsible actions in digital environments; it involves the management of digital stress, workload, and distraction; it relates to the use of digital media for participation in political and community actions and the use of personal digital data for well-being benefits; it emphasizes that all actions should consider their implications for the human and natural environment; and, it calls for a balance between digital and real-world interactions (Beetham 2016). Regardless of the viewing angle and accounting for the fact that technology is a significant part of consumers’ lives, it is evident that digital well-being intersects with physical, emotional, intellectual, spiritual, social, vocational, environmental and financial aspects of general well-being.

Several digital well-being initiatives were recently instated by some countries, while informal groups gathered around issues of digital well-being have also gained more popularity and public recognition. For example, the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma on issues of addiction and privacy loss as a result of social media use has created a broad public debate (Petrescu and Krishen 2020). However, awareness of the problem concerning addictive technology (Alter 2018) had already been raised by some earlier movements that caught the attention of the media, such as "National Day of Unplugging" (Foot 2014), or the later "Time Well Spent" movement that promoted the idea that technology distorts people’s everyday reality, repeatedly shredding their attention (Center for Humane Technology 2018).

Threats to digital well-being in the tourism domain are also becoming more visible. Threats to digital well-being that emanate from tourism offerings are mostly objective and external in nature, generated by the lack of operational digital resources, a paucity in digital skills of tourism service providers, the absence of supportive regulatory or organizational environments, or caused by a digital divide (Herdin and Egger 2017). These threats can be manifested by the absence of ICT use, the prevalence of an analogue offer; or the use and application of ICT can be excessive and inadequate. On the other hand, threats to digital well-being could come from the tourists themselves, generated by the same objective factors as in the case of tourism offerings (lack of skills, resources, etc.) or they can be more subjective in nature, manifested in the form of problematic, excessive or addictive use of technology during travel. The latter could also include a lack of interest in digital well-being, or deliberate sabotage of technology (Weaver and Moyle 2019).

The spillover of stress related to technology from everyday life to tourism experiences seriously hampers one of the central roles of tourism, namely to provide hedonic, altruistic, and meaningful experiences (Cai et al. 2019; Kay Smith and Diekmann 2017; Pearce and Gretzel 2012; Wang et al. 2016). Apart from positive outcomes of technology-mediated experiences for consumers' well-being and increased efficiency for tourism providers, the incorporation of standard technology into tourism settings, coupled with tourism-specific solutions, has brought about many threats to well-being (Stankov and Filimonau 2019). In the tourism domain these negative consequences of ICT use are usually reflected through concepts such as addictive travel technologies; digital distractions (e.g. pulling attention away from tourist experience or even deaths by travel selfie); technostress/information overload before/during/after travel; digital depersonalization of travel experiences (e.g. through complete automation); increased FOMO (fear of missing out); technology isolation on vacation; and, value co-destruction, to mention a few. The prevalence of ICT in tourism is no surprise given that the tourism industry has always been eager to adopt the latest technology to make its operations more efficient (Xiang 2018) while sometimes forgetting the human side of the tourist experience (Stankov and Gretzel 2020). Furthermore, with the proliferation of technology in all aspects of everyday life and the emergence of a smart development paradigm, the reliance on technology has become paramount for many tourism providers in their effort to offer compelling experience co-creation opportunities and superior service delivery and, thus, their need to achieve sustained competitiveness (Gretzel et al. 2015).

This paper pinpoints the concept of digital well-being as one of the new responsibilities of the tourism industry in this era of technology dependence, technostress and negative spillover effects. Its goal is to elaborate the need for maintaining digital well-being during tourist experiences by sustaining balanced technology use, by keeping the integrity of tourist experiences, and by maintaining tourism’s restorative benefits. To this end, we first map the most prominent digital well-being approaches in society and the tourism industry. By doing so, we identify new research directions in digital well-being in tourism that reflect new roles and responsibilities for the tourism industry in relation to experience design and product/service creation.

2 Mapping digital well-being initiatives

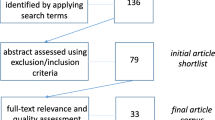

For the most part, digital well-being as a coping strategy to overcome the negative impacts of technology use was popularized by informal and formal initiatives aimed at raising awareness of the problem and offering support and solutions (Stankov and Filimonau 2020; Vanden Abeele 2020). Responses to the issues of technostress and digital harm range from actions at individual and societal levels, including institutional programs and regulation (Marsden 2019), to efforts by technology providers (Fig. 1). From the hardware perspective, the main mass enablers of digital well-being (and digital stress, as well) are smartphones, tablets and wearables (Abraham 2015). According to digital well-being agendas, these devices should provide services to support users' well-being (for example, m-health mobile applications), or be capable of detecting, monitoring and mitigating unfavorable user states and behaviors (Monge Roffarello and De Russis 2019). Leaning on the momentum of digital well-being movements, technology providers have started to develop solutions and speak openly about problematic issues that might emerge when using their products. For example, Google's Digital Wellbeing and Apple's Screen time initiatives are examples of an emerging family of digital tools designed to help people to develop a healthier and conscious relationship with technology (McAlaney et al. 2020). As part of the technological response to negative technology impacts, some other products and tech-focused initiatives have emerged, such as social companion robots, more responsible and humane technology, coupled with efforts to promote calm or biophilic designs, technology-assisted mindfulness, downgrading smartphones to so-called dumb phones, etc. (Stankov et al. 2020a, b; Stankov and Gretzel 2020) (Fig. 1).

As we have already noted, due to omnipresent technology, the discontinuity between everyday life and tourism diminishes (MacKay and Vogt 2012). The resulting digital elasticity between the two realms (Pearce and Gretzel 2012) holds significant repercussions for tourists' digital well-being and the responsible management of tourist experiences. Besides, tourists have been empowered by various ICT solutions closely integrated into all travel phases, which further encourages extensive technology use. No longer able to ignore the potential negative effects, the tourism industry has started to respond to the problem with its own digital well-being initiatives (Fig. 1). However, most of the impetus still comes from consumers. Technology use on vacation clashes with emerging lifestyles, beliefs, value systems, specific health needs and areas of consumer activism focused on different aspects of well-being, such as digital minimalism, slow technology initiatives, technology restrictions based on religious beliefs (e.g. travelers following Shabbat laws) or health issues (e.g., electromagnetic hypersensitivity), all the way to techlash (e.g. boycotts of technology companies), Neo-Luddism (perceptions of technology as a threat to humanity and the natural world) and anti-5G activism (i.e., the opposition to or destruction of telecommunications infrastructure seen as harmful to living beings).

In essence, two types of responses to enable digital well-being can be distinguished. One is an avoidance strategy, and the other is the acceptance of alternative technologies. In both cases, the main goal is reducing or eliminating the harmful effects of technology use and achieving an overall state of well-being. Individual consumers either adopt technology that promotes well-being during travel or avoid harmful technologies in general or at least while on vacation. At the society level, initiatives and regulations exist that encourage or mandate the use of well-being or safety-focused technologies, while others aim at reducing technology use overall, curtail specific types of uses, or limit technology use in particular settings (e.g. no texting while driving, no use of selfie sticks in public museums). Similarly, technology providers either create specific technologies that foster well-being and equip existing devices or software with well-being options or develop technology that facilitates less intensive or distracting technology uses.

The avoidance approach in the tourism industry is reflected in creating tech-scarce tourism, such as, "no-internet" and "no-smartphone" initiatives (e.g. signal jamming, phone-free spa zones, no-selfie destinations) or disconnected travel or digital detox retreats. The acceptance approach is reflected in the embracement of technology (tech-savvy tourism) to provide technology-facilitated well-being experiences, as seen in technology-focused wellness programs (artificial intelligence-based spa programs, virtual reality and augmented reality-based meditation, integration of fitness trackers and exercise application into wellness programs, persuasive health technology with hyper-personalization and/or gamification of well-being experiences), sleep technology (e.g. sleeping pods at airports), technology-enabled mindfulness programs (e.g., headphones with an electroencephalogram or brain-sensing headbands for mediation monitoring). It also encompasses efforts to integrate technologies into touristic offerings in a way that supports mindful experiences (Stankov et al. 2020a, b) and leads to stewardship for the destination (Kang and Gretzel 2012).

Another acceptance-related strategy is the endorsement of responsible technology use through digital well-being focused advertising campaigns and initiatives. For instance, a recent promotional campaign by Tourism New Zealand encourages travelers to refrain from constantly comparing their experiences to those posted on social media and from mindlessly copying the photo-taking behaviors of social media influencers. Instead of traveling ‘under the social influence’, the ad asks tourists to use their smartphones to discover and capture their unique, personal experiences (Picheta 2021). Particularly noteworthy are smart tourism development strategies which try to overcome the social and environmental drawbacks of extensive technology use in smart destinations. Referred to as ‘wise’ destinations (Coca-Stefaniak 2020), these destinations make sustainability and well-being their primary concerns and implement technological solutions to achieve them.

3 Digital well-being continuum from everyday life to tourism

Since well-being, including digital well-being, as a concept has a high level of granularity in everyday life, encompassing many individual and external factors (Scaria et al. 2020), various issues emerge for the tourism domain as well. The following section conceptualizes a digital well-being continuum between everyday life and the tourism domain, raising new questions and pointing to new roles and responsibilities that emerge for the tourism industry (Fig. 2).

3.1 Understanding digital well-being as a new well-being philosophy: responsibilities and convergence of approaches

Digital well-being needs result from a complex mix of socioeconomic, psycho-physiological and technological influences that all converge on the individual consumer struggling to maintain a balance (Vanden Abeele 2020). However, digital well-being cannot be created solely relying on individual capabilities and therefore is not an exclusively individual responsibility (Beetham 2016; Nansen et al. 2012). Similarly, Gui et al. (2017) state that digital well-being is a state to be realized not only by the individual via personal skills but also one that relies on broader, societal characteristics that determine norms and establish common patterns of behavior. Society, in this regard, is understood as the collective of actors that have the power to affect individual levels of digital consumption. This includes technology providers who should support (Grissemann and Stokburger-Sauer 2012) the co-creation of digital well-being together with consumers.

Tourism, as a highly technology-dependent industry, both in service provision and delivery, represents a continuation of digitally-led everyday consumer lives. As such, it represents the verge where digital well-being philosophy meets the existing tourism philosophy and triggers re-thinking towards a new, digital well-being focused mindset. In order to sustain digital well-being within the tourism domain, tourism policy-makers and tourism industry members should first acknowledge the issue in order to be able to embrace the new roles and responsibilities that emerge from it.

While the issues brought about by technology over- or mis-use are becoming more pertinent and therefore apparent to the tourism industry, the industry’s complex structure and heterogeneity of players represent significant challenges in embracing digital well-being as the new and generally accepted core of tourism philosophy (Pyke et al. 2016). Here, additional efforts have to be put forward to facilitate the convergence of existing digital well-being approaches for everyday life (for example, understanding of digital well-being in the EU's digital transformation initiatives as a primary issue in the health domain) and those currently present in the tourism industry (for example, holistic and unified approach to digital well-being in the form of digital wellness promoted by the Global Wellness Institute). Digital well-being requires unique boundary-crossing and demands that specialists who have never before worked together now need to collaborate and co-create new solutions. This multi-sector, boundary-spanning approach is novel (Abraham 2015) and requires rethinking also in the fields of tourism education and training, academic research and industry practice. Smart tourism development could potentially facilitate the process with its emphasis on government-industry collaborations and new governance mechanisms but currently fails to embrace digital well-being as a core goal.

3.2 Integrating digital well-being into the fabric of tourism

After incorporating digital well-being into the general tourism philosophy, the next step in moving forward on the digital well-being continuum would be to address digital well-being as a tourism product resource. This could be done through the creation of new, or adjusting of existing business policies that support achieving digital well-being for specific stakeholders in the tourism domain. In either case, the framing of digital well being for tourism purposes will face most of the well-being barriers identified by Pyke and colleagues (2016). These barriers are related to digital well-being as being too broadly defined and having different interpretations with varying underlying consumer preferences. Digital well-being branding, although emerging among some technology providers (e.g., Samsung Health product line) is still novel and inconsistent. The network of digital well-being initiatives is in its infancy, despite some non-profit organizations that push the agenda (for example, Center for Humane Technology), and some state-run initiatives and projects for digital well-being targeted explicitly at youth or older people. Initiatives in tourism are dispersed and uncoordinated.

Some consumer trends are unfortunately going against the digital well-being agenda, such as shorter trips or over-dependency of tourism experiences on technology. Infrastructure for digital well-being, less prevalent in some locations or spaces, can present a significant barrier to digital well-being, either by its absence or by its inadequacy. Financing of digital well-being investments represents an issue for fragmented, small business-heavy tourism sectors that typically rely on the initiatives, research, product and service development of major technology and tourism players. Thankfully, well-being products such as stress and energy monitoring and mindfulness exercises first introduced by the major wearable technology providers are now becoming a standard feature for smaller manufacturers as well, opening up the playing field and introducing less costly options to the market.

Since there are different approaches to measuring both individual and national well-being, digital well-being policies in tourism should be adopted at both the state level (Hartwell et al. 2013), and by the industry (horizontally and vertically). For instance, digital well-being could be understood as an underlying philosophy and could be assessed and tackled in collaboration between tourism and technology providers (Mizrachi and Gretzel 2020). In that case, all smaller players in the supply chain (for example, in the context of global distribution systems it would be online travel agencies and destination service providers) would be, by default, sensitized and equipped to participate in enabling digital well-being for consumers, thus, promoting digital well-being through mass customization.

Well-being is already an integral part of organizational ethics in tourism (Pearce et al. 2001), and it should cover all stakeholders, not just tourists. Here, digital well-being concerns of tourism workers stand out as one of the most significant issues faced in the tourism domain. Intense information overload, stress and burnout due to over-use of technology in the workplace are critical issues to be considered (Farrish and Edwards 2019). Furthermore, as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is an expectation that more jobs, including tourism-related ones, will become more digital and virtual (Gretzel et al. 2020), thus, making them more susceptible to technostress. Therefore, in addition to already existing solutions that address corporate well-being, there are new initiatives to develop comprehensive platforms for increasing employees' engagement in digital well-being through initiatives facilitated by artificial intelligence and gamification techniques (Guerrini 2019).

3.3 Digital well-being tactics: from luxury to mainstream and back

Digital well-being as a tourism product resource is currently mostly considered to be a luxury (Stankov and Filimonau 2020). This is in line with a common perception of wellness as a luxury activity through which individuals actively seek good health, which is further fueled by current trends in tourism and marketing efforts implemented by the tourism industry (Fickel et al. 2018; Scaria et al. 2020). For example, it would be a severe disadvantage for a luxury hotel to not be equipped with wellness facilities (Heyes et al. 2015), while they are not expected in budget hotels. In terms of digital well-being, there are views that consumers who use their phones the most are the ones with the least access to digital detox programs (Buck 2018). Similarly, as an important emerging aspect of subjective well-being, the pursuit of mindfulness is mostly the interest of those less socioeconomically burdened (Andrews 2009; Stankov et al. 2020a, b). Furthermore, most current prominent programs for digital well-being, such as the use of Industry 4.0 technologies in the health tourism sector (Parekh et al. 2020; Wong and Sa'aid Hazley 2020) and in wellness service creation and provision (e.g., virtual reality spa treatments, ultrasound therapy or data-driven wellness retreats) (Baldwin et al. 2020; Parker 2020), still rely on relatively expensive technologies.

There are views that digital well-being, like some other wellness trends, promises more than it can deliver (Pardes 2018). The reason for this lies partly in the lack of strict guidelines for tourism providers in relation to creating or conserving digital well-being. Here, we continue our argument that mass technology and large-scale tourism providers should lead and promote the trend and pass it on to other players within the tourism supply chain, allowing for the mass customization of the digital well-being agenda. Furthermore, to create a customized product for different players across the diverse tourism market, a generally accepted notion of digital well-being is needed to guide such mass customization (Cecchinato et al. 2019). A commonly agreed upon the conceptualization of digital well-being should make the whole agenda more tangible for all stakeholders, providing a better understanding of consumer needs and expectations within different aspects of the tourist experience and the new roles and requirements expected from providers.

There are many arguments in favor of turning digital well-being into a mass trend for the tourism industry. One of the main practical arguments lies in the fact that many aspects of digital well-being could be delivered using existing technologies (e.g. smartphones and tablets) already globally available. New low-cost wearable technologies related to connected health and specialized wellness technology (well-tech) gadget emerge rapidly (Pasqualini 2020; Perez-Aranda et al. 2019). The awareness of technostress is often already present among younger generations that are the most frequent and passionate users of technologies (Glazzard and Stones 2019). Innovation in well-being is now more than ever related to the growing interest in smart tourism environments and destinations (Coca-Stefaniak 2020; Hjalager and Flagestad 2012). By finding new ways to use pervasive smart technologies for wellness purposes (Lee et al. 2018; Trencher and Karvonen 2019), a door for mass application and widespread digital well-being recognition is opening. Another argument in support of mainstreaming digital well-being in tourism is that the negative consequences of technology use disproportionally affect vulnerable and marginalized groups (Demir and Kutlu 2016; Soule et al. 2016). Providing them with access to digital well-being using readily available means within well-known tourism experiences could be seen as a valuable coping strategy and a new target for the emerging responsible tourism agenda.

It must be noted that the advanced use of digital well-being concepts should still be welcomed for luxury tourism and will continue to create opportunities for product differentiation and further development of the traditional wellness tourism market. In conjunction with the current notion of unplugged tourism, luxury tourism can continue to provide more extreme technology-free leisure and recreation offerings, focusing on the complete cleansing of the mind and body, even including the treatment of technology addictions (Pawłowska-Legwand and Matoga 2020). We label this continuing trend "digital well-being mastery" and expect that it will remain reserved for those who actively seek to achieve good health and well-being within the luxury or unconventional tourism sector (Bjelajac et al. 2020).

4 Concluding remarks

With this paper, we intended to raise awareness of digital well-being as an emerging paradigm that will significantly affect tourism. Situated on the crossroads between subjective and objective well-being, digital well-being is an issue that requires multidisciplinary approaches (Cecchinato et al. 2019) and a proper theoretical framing when applied to the tourism domain. We tried to offer the first step in this direction.

We believe that most if not all types of tourist experiences represent an optimal setting for exploring and applying digital well-being agendas. The majority of contemporary tourism experiences is penetrated by everyday due to technology usage (Pearce and Gretzel 2012). At the same time, tourism can still offer discontinuity (e.g., changes in settings and expected behaviors), providing a proper context for consumers to reflect on their personal relationship with technology (Stankov et al. 2019). Furthermore, eudemonic and hedonic properties of tourist experiences and their close relationship with general well-being (Filep 2014) are other strong arguments for conceptualizing tourism experiences as central to overall digital well-being efforts. Importantly, this should encourage tourism providers to consider digital well-being as a new philosophy and responsibility but also a valuable business strategy.

The digital well-being continuum could inform a new agenda for further research on digital well-being opportunities and challenges in tourism. This research could also encompass more detailed exploration of the phenomenon focusing on quantification and measuring the influence of digital well-being on tourist experiences. More business-oriented research focused on the selection of the most profitable path for digital well-being integration into touristic offerings, or the exploration of the global impact of digital well-being trends on the tourism industry are also important topics that need to be tackled.

References

Abraham DP (2015) Cyberconnecting: the three lenses of diversity. Gower Publishing Limited, London

Alter AL (2018) Irresistible: the rise of addictive technology and the business of keeping us hooked. Penguin Books, New York

Andrews SM (2009) Is mindfulness a luxury? Examining the role of socioeconomic status in the relationship between dispositional mindfulness and psychological distress. Thesis, Southern Illinois University Carbondale

Baldwin J, Haven-Tang C, Gill S, Morgan N, Pritchard A (2020) Using the perceptual experience laboratory (PEL) to simulate tourism environments for hedonic wellbeing. Informat Technol Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00179-x

Beetham H (2016) What is “digital wellbeing”? https://design-4-learning.blogspot.com/2016/03/what-is-digital-wellbeing.html. Accessed 19 July 2020

Bjelajac D, Đerčan B, Kovačić S (2020) Dark skies and dark screens as a precondition for astronomy tourism and general well-being. Informat TechnolTourism. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00189-9

Buck S (2018) Is unplugging the new luxury reserved for the elite? https://www.travelandleisure.com/travel-news/who-gets-to-unplug. Accessed 01 Dec 2018

Cai W, McKenna B, Waizenegger L (2019) Turning it off: emotions in digital-free travel. J Travel Res 59(5):909–927. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519868314

Cecchinato ME, Rooksby J, Hiniker A, Munson S, Lukoff K, Ciolfi L, Thieme A and Harrison D (2019) Designing for digital wellbeing: a research and amp; practice agenda. Extended abstracts of the 2019 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290607.3298998

Center for humane technology (2018) The problem. https://humanetech.com/problem. Accessed 25 Aug 2018

Irish Internet Safety Awareness Centre. Managing your online wellbeing. Webwise.Ie. https://www.webwise.ie/news/managing-online-wellbeing/. Accessed 10 Sept 2019

Coca-Stefaniak JA (2020) Beyond smart tourism cities: towards a new generation of “wise” tourism destinations. J Tour Futures. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-11-2019-0130 (ahead-of-print)

Demir Y and Kutlu M (2016) The relationship between loneliness and depression: mediation role of internet addiction. Educ Process Int J 5(2):97–105. https://doi.org/10.12973/edupij.2016.52.1

European institute of innovation and technology (2018) EIT digital model. European institute of innovation and technology (EIT). https://eit.europa.eu/our-activities/innovation/eit-digital-model. Accessed 27 Sept 2020

Farrish J, Edwards C (2019) Technostress in the hospitality workplace: is it an illness requiring accommodation? J Hospit Tour Technol 11(1):83–92. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-07-2017-0046

Fickel L, Lymann R, Wallebohr A, Huilla J (2018) Understanding of the term “wellness” among hoteliers and Swiss wellness hotel employees. Int J Spa Wellness 1(3):178–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/24721735.2019.1596657

Filep S (2014) Moving beyond subjective well-being: a tourism critique. J Hospital Tour Res 38(2):266–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348012436609

Foot K (2014) The online emergence of pushback on social media in the united states: a historical discourse analysis. Int J Commun 8:1313–1342

Glazzard J, Stones S (2019) Social media and young people’s mental health. Select Topics Child Adolesc Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.88569

Google (2021) Digital wellbeing through technology. Google digital wellbeing. https://wellbeing.google/. Accessed 30 Jan 2021

Gretzel U, Sigala M, Xiang Z, Koo C (2015) Smart tourism: foundations and developments. Electron Mark 25(3):179–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-015-0196-8

Gretzel U, Fuchs M, Baggio R, Hoepken W, Law R, Neidhardt J, Pesonen J, Zanker M, Xiang Z (2020) e-Tourism beyond COVID-19: a call for transformative research. Informat Technol Tourism 22(2):187–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00181-3

Grissemann US, Stokburger-Sauer NE (2012) Customer co-creation of travel services: the role of company support and customer satisfaction with the co-creation performance. Tour Manage 33(6):1483–1492. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TOURMAN.2012.02.002

Guerrini F (2019) L3W: a comprehensive platform to increase employees’ wellbeing through AI and gamification techniques. https://www.eitdigital.eu/newsroom/news/article/l3w-a-comprehensive-platform-to-increase-employees-wellbeing-through-ai-and-gamification-techniques/. Accessed 07 Jan 2021

Gui M, Fasoli M, Carradore R (2017) Digital well-being Developing a new theoretical tool for media literacy research. Italian J Sociol Educ 9(1):155–173. https://doi.org/10.14658/pupj-ijse-2017-1-8

Hartwell H, Hemingway A, Fyall A, Filimonau V, Wall S, Short N (2013) Building tourism and wellbeing policy: engaging with the public health agenda in the UK. In: Smith M, Puczko L (eds) Health tourism and hospitality: spa, wellness and medical travel, 2nd edn. Routledge, Abingdon, pp 397–402

Herdin T, Egger R (2017) Beyond the digital divide: tourism, ICTs and culture. Int J Dig Cult Elect Tour 1(1):1–1. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijdcet.2017.10009880

Heyes A, Beard C, Gehrels S (2015) Can a luxury hotel compete without a spa facility?: opinions from senior managers of London’s luxury hotels. Res Hospital Manag 5(1):93–97

Hjalager A-M, Flagestad A (2012) Innovations in well-being tourism in the Nordic countries. Curr Issues Tour 15(8):725–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2011.629720

Kang M, Gretzel U (2012) Effects of podcast tours on tourist experiences in a national park. Tour Manag 33(2):440–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TOURMAN.2011.05.005

Kay Smith M, Diekmann A (2017) Tourism and wellbeing. Ann Tour Res 66:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.006

Lee H, Lee J, Chung N, Koo C (2018) Tourists’ happiness: are there smart tourism technology effects? Asia Pac J Tour Res 23(5):486–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2018.1468344

MacKay K, Vogt C (2012) Information technology in everyday and vacation contexts. Ann Tour Res 39(3):1380–1401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.02.001

Marsden P (2019) Humane: a new agenda for tech (summary and video). Digitalwellbeing.Org. https://digitalwellbeing.org/humane-a-new-agenda-for-tech-speed-summary-and-video/. Accessed 08 Jan 2021

Marsden P (2020) What is digital wellbeing? A list of definitions. Digitalwellbeing.Org. https://digitalwellbeing.org/what-is-digital-wellbeing-a-list-of-definitions/. Accessed 07 Jan 2021

McAlaney J, Aldhayan M, Almourad MB, Cham S Ali R (2020) Predictors of acceptance and rejection of online peer support groups as a digital wellbeing tool. In: Rocha Á, Adeli H, Reis L, Costanzo S, Orovic I, Moreira F (eds) Trends and innovations in information systems and technologies. WorldCIST 2020. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. Springer, Cham, pp 95–107

Mizrachi I, Gretzel U (2020) Collaborating against COVID-19: Bridging travel and travel tech. Informat Technol Tour 22(4):489–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00192-0

Monge Roffarello A, and De Russis L (2019). The race towards digital wellbeing: issues and opportunities. Proceedings of the 2019 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300616

Nansen B, Chakraborty K, Gibbs L, MacDougall C, Vetere F (2012) Children and digital wellbeing in australia: online regulation, conduct and competence. J Child Media 6(2):237–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2011.619548

Pardes A (2018) Google and the Rise of “digital well-being.” https://www.wired.com/story/google-and-the-rise-of-digital-wellbeing/. Accessed 08 Jan 2020

Parekh J, Jaffer A, Bhanushali U, Shukla S (2020) Disintermediation in medical tourism through blockchain technology: an analysis using value-focused thinking approach. Informat Technol Tour. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00180-4

Parker JL (2020) Wellness travel gets a high tech upgrade. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jenniferleighparker/2020/02/17/wellness-travel-gets-a-high-tech-upgrade/. Accessed 07 Jan 2020

Pasqualini M (2020) Wellbeing: the next disrupted industry by tech. Medium. https://medium.com/sharing-by-mirco-pasqualini/wellbeing-the-next-disruptive-industry-by-tech-a276828aac50. Accessed 07 Jan 2020

Pawłowska-Legwand A, Matoga Ł (2020) Disconnect from the digital world to reconnect with the real life: an analysis of the potential for development of unplugged tourism on the example of Poland. Tour Plann Develop. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2020.1842487

Pearce P, Gretzel U (2012) Tourism in technology dead zones: documenting experiential dimensions. Int J Tour Sci 12(2):1–20

Pearce P, Filep S, Ross G (2011) Tourists, Tourism and the Good Life. Routledge, New York

Perez-Aranda J, González Robles EM, Urbistondo PA (2019) Sport-related physical activity in tourism: an analysis of antecedents of sport based applications use. Informat Technol Tour. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-019-00161-2

Petrescu M, Krishen AS (2020) The dilemma of social media algorithms and analytics. J Market Anal 8(4):187–188. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41270-020-00094-4

Picheta R (2021) New Zealand tells travelers to stop copying other people’s travel photos. https://edition.cnn.com/travel/article/new-zealand-tourist-photos-campaign-scli-intl/index.html. Accessed 30 Jan 2020

Pyke S, Hartwell H, Blake A, Hemingway A (2016) Exploring well-being as a tourism product resource. Tour Manag 55:94–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.02.004

Scaria D, Brandt ML, Kim E, Lindeman B (2020) What is wellbeing? In: Kim E, Lindeman B (eds) Wellbeing. Success in Academic Surgery. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-29470-0_1

Soule LC, Shell LW, Kleen BA (2016) Exploring internet addiction: demographic characteristics and stereotypes of heavy internet users. J Comp Informat Syst 44(1):64–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2003.11647553

Stankov U, Filimonau V (2019) Reviving calm technology in the e-tourism context. Serv Ind J 39(5–6):343–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2018.1544619

Stankov U and Filimonau V (2020) Technology-assisted mindfulness in the co-creation of tourist experiences. In Z. Xian, M. Fuchs, U. Gretzel, and W. Höpken (Eds.), Handbook of e-Tourism. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05324-6

Stankov U, Gretzel U (2020) Tourism 4.0 technologies and tourist experiences: a human-centered design perspective. Informat Technol Tour 22:477–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00186

Stankov U, Filimonau V, Slivar I (2019) Calm ICT design in hotels: a critical review of applications and implications. Int J Hosp Manag 82:298–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.10.012

Stankov U, Filimonau V, Gretzel U, Vujičić MD (2020a) E-mindfulness – the growing importance of facilitating tourists’ connections to the present moment. J Tour Fut 6(3):239–245. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-11-2019-0135

Stankov U, Filimonau V, Vujičić MD (2020b) A mindful shift: an opportunity for mindfulness-driven tourism in a post-pandemic world. Tour Geogr 22(3):703–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1768432

Trencher G, Karvonen A (2019) Stretching “smart”: advancing health and well-being through the smart city agenda. Local Environ 24(7):610–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2017.1360264

Vanden Abeele MMP (2020) Digital wellbeing as a dynamic construct. Commun Theory. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtaa024

Wang D, Xiang Z, Fesenmaier DR (2016) Smartphone use in everyday life and travel. J Travel Res 55(1):52–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514535847

Weaver DB, Moyle BD (2019) ‘Tourist stupidity’ as a basic characteristic of ‘smart tourism’: challenges for destination planning and management. Tour Recreat Res 44(3):387–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2019.1637611

Wong BKM, Sa’aid Hazley SA (2020) The future of health tourism in the industrial revolution 4.0 era. J Tour Fut. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-01-2020-0006

Xiang Z (2018) From digitization to the age of acceleration: on information technology and tourism. Tour Manag Perspect 25:147–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TMP.2017.11.023

Acknowledgements

This publication is based upon work from COST Action CA19136—International Interdisciplinary Network on Smart Healthy Age-friendly Environments and COST Action CA19142—Leading Platform for European Citizens, Industries, Academia and Policymakers in Media Accessibility supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stankov, U., Gretzel, U. Digital well-being in the tourism domain: mapping new roles and responsibilities. Inf Technol Tourism 23, 5–17 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-021-00197-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-021-00197-3