Abstract

Purpose

Weight bias can negatively impact health, and schools may be risky environments for students with obesity. We aimed to explore teachers’ perceptions of the school experiences and academic challenges of students with obesity.

Methods

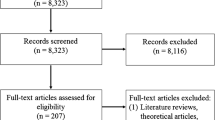

We conducted interviews with 22 teachers in the Northeast, mid-Atlantic, and Midwest in July–August 2014. All interviews were transcribed verbatim, coded, and analyzed for important themes by two researchers using the immersion/crystallization approach.

Results

Most teachers felt that students with obesity were more likely to have academic difficulties. Two main perceptions of the reasons for these difficulties emerged: (1) obesity led to lower self-esteem that caused students to participate less, and (2) poorer nutrition, increased screen time, and reduced physical activity were simultaneously causing obesity and poorer academic performance. A few teachers described colleagues who felt students with obesity were not as motivated to work hard in school as their peers. Many teachers described school health promotion efforts focused on weight reduction that could exacerbate weight stigma and risk of disordered eating.

Conclusions

Students with obesity, particularly girls, may be at risk for negative social and academic experiences in K-12 schools and may be perceived as struggling academically by their teachers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of childhood obesity in the United States has tripled since 1980 [1], becoming a major public health concern. Children with obesity are at an increased risk for a range of harmful health outcomes, including Type 2 diabetes mellitus and high blood pressure, during both childhood and adulthood [2–5].

An important aspect of the childhood obesity epidemic is the impact of weight-related discrimination, or weight bias, on children’s wellbeing. Weight bias is rooted in widely-held stereotypes that present individuals with obesity as possessing several negative characteristics, typically including laziness and a lack of motivation, self-discipline, competence, and morality [6, 7], and experiences of perceived weight discrimination are widespread [8]. Experiencing weight bias can have a direct negative impact on health, as it is linked with binge eating disorder [9–11] and disordered weight control behaviors [10]. Weight bias can also lead to reduced educational, social, and economic opportunities for adolescents and young adults with obesity, especially girls and women, who are at risk for lower educational attainment, income, and likelihood of marriage compared to their non-obese peers [12, 13].

Although the impact of weight bias on social and economic opportunities and wellbeing in adults is well documented, the possible impact of weight bias on children, particularly their exposure to weight bias from the adults and educational institutions that determine their future prospects, is less well understood. Existing research indicates that the school environment may be particularly risky for students with obesity in terms of exposure to weight-based teasing. Estimates of the prevalence of weight-based teasing or bullying victimization among children and adolescents range from 24 to 36 % [9, 14, 15]. Additionally, several studies examining the academic performance of students with obesity have found poorer performance compared to non-obese students when using subjective measures like grades [16–18], but no difference when using objective measures like standardized test scores [17–22], suggesting that students with obesity may be less successful in school despite having the same cognitive and academic capabilities.

However, the reasons for this gap between ability and school performance for heavier students are not clear. The elements of school climate that may be driving this gap have not been identified. While lowered perceptions of ability by teachers, i.e. weight bias on the part of teachers, could conceivably play a role, other factors, such as peer relationships, school policies surrounding bullying, school policies that promote wellness, and school culture, could also drive a gap between perceived ability and objective ability. Physical education instructors report negative attitudes towards students with obesity [23, 24], but less is known about classroom teachers’ attitudes towards students specifically. A small study of 113 junior and senior high school teachers from 1999 found between 20 and 25 % of teachers had negative perceptions of people with obesity in general, but this was not specifically linked with negative perceptions of students or of academic ability for students with obesity [25]. The interactions between students with obesity and their teachers and peers at school are not well understood, limiting our understanding of how weight-related discrimination may impact the health and educational trajectories of students with obesity and our ability to determine strategies to improve the educational prospects of these students.

Given that there is no scale designed specifically to measure teachers’ attitudes towards students with obesity, and given that the nuances of teacher and student interactions with relation to student weight status have not been fully explored in the research literature, this study utilized a qualitative design in order to explore, in detail, teachers’ perceptions of the academic and social experiences of students with obesity. Qualitative, rather than quantitative, methods were used in order to be able to explore teachers’ perceptions in richer detail than may have been possible with a close-ended survey with items and responses pre-determined by researchers. Our goal was to improve researchers’ understanding of how teachers, students, and the school environment can support or hamper the academic and social progress of students with obesity by gathering teachers’ perspectives on these issues.

Methods

Participants

We conducted interviews with a convenience sample of 22 teachers in the Northeast, the mid-Atlantic, and the Midwest regions of the US. Our eligibility criteria were that the teachers taught in a K-12 public school setting and focused on an academic subject (or general classroom teaching in elementary settings), given that we were specifically interested in exploring reasons why there is a gap for obese students between their objectively measured academic ability and subjective measures of their performance such as grades. Teachers were recruited using listservs for local graduates of education schools, identified by colleagues at our university involved in public education, and by obtaining potential participant contact information from colleagues involved in public education. We also asked recruited participants for suggestions of additional participants. Teachers were given a $25 gift card from amazon.com as an incentive for participation.

Instruments

We conducted the interviews using a standard interview protocol with a series of open-ended questions exploring teachers’ perceptions of the social and academic experiences of students with obesity (see the protocol in Fig. 1). The questions were developed de novo by the researchers to probe further into phenomena that have been observed previously, including the influence of school climate [9], the increased risk of experiencing bullying and teasing among students with obesity [11–14], and the observed gaps between standardized test scores and subjective assessments of students with obesity [17–21]. Experts in weight-related discrimination and public health, whose work focused primarily on adolescents and young adults, were approached at a seminar on weight discrimination and asked to critically review the questions before the study began. The questions were further edited based on this review and then finalized.

Procedure

The interviews were conducted in July–August 2014 by a single interviewer (M.R.). The interviewer asked each the respondents each of the open-ended questions, following up with spontaneous probing and clarifying questions with necessary. Two interviews were conducted in-person; the remaining took place via telephone due to travel constraints. We audio-recorded all interviews and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Two investigators (M.R. and E.K.) read the interview transcripts and met to conduct content analysis, following the principles of the immersion-crystallization approach [26]. This approach to qualitative analysis of text involves researchers’ immersing themselves in the data by reading the text (here, of the interview transcripts) in detail, and continuing to examine the text until themes or patterns from the text “crystallize.” At this point, the researchers suspend the process of immersion (i.e. examining the text) in order to reflect on the insights or patterns that have emerged. After examining the transcripts in depth, we first discussed broad topic categories that emerged across the transcripts that could be used to organize more detailed themes, and then finalized a codebook for coding the data according to these broader organizational themes. NVivo for Mac qualitative data coding software (Victoria, Australia: QSR International) was used to organize coded data, resulting in a database of key passages of text from across the interviews that were organized by code (for example, all text passages related to teachers’ perceptions of bullying were placed in the same field of the database, so that it would be possible to reflect again on the data to identify more detailed themes within that category). We double-coded six (25 %) of the interviews and met to compare coding results, finding a 76 % agreement in coding. After discussing discrepancies, the codebook was further refined and one investigator (M.R.) conducted the remaining coding.

With all of the textual data organized, the two investigators then reviewed the text again, sorted by code, continuing to use the immersion/crystallization process to identify important themes that had emerged both within and across codes. We reviewed transcripts and discussed the themes that emerged until reaching consensus on key themes.

Results

Sample description

Our final sample included 22 public school teachers. Half taught high school (n = 11), while six (27 %) taught middle school and five (23 %) taught elementary school. As is seen nationally [27], most were female (n = 19, 86 %). Most described their school district as urban (n = 16, 73 %). Teachers represented six states across the Northeast, the mid-Atlantic, and the Midwest. Participating teachers’ years of experience ranged from 3 to 23 years (mean 10.6 years, SD 8.0).

Theme I: bullying, social exclusion, and the intersection with gender

Most teachers responded that students with obesity were more likely to be bullied than students without obesity (Table 1). Several teachers responded that students with obesity were also more likely to be perpetrators of bullying and teasing, with most of these teachers interpreting this as a defense or emotional coping mechanism.

Several teachers felt students with obesity fell into a few stereotypical personality types. Some teachers perceived that students with obesity were typically “class clowns” while others thought that students with obesity tended to be on one extreme or the other, either a class clown or very reserved and quiet. One teacher described this by saying, “They overcompensate and they’re the class clown sometimes, or sometimes they’re just extremely quiet. Not willing to ask questions or draw any extra attention to themselves. I think it can go in either direction.”

Several teachers, particularly in middle and high schools, indicated that the social impact of weight bias, and the negative impact of obesity on body image, was worse for girls. One teacher said, “Particularly for girls, I think there is a sense of like maybe feeling ostracized because they don’t look a certain way.” These gender differences may widen with age and were linked with dating and appearance pressures on girls and women. For example, another teacher said, “I think that little remarks are made often, especially when I hear boys say things like, ‘That girl thinks she’s hot and what is she wearing?’” Two teachers felt the dress code at their high school (i.e., shorts being too short or wearing tank tops) was more strictly enforced for girls with obesity than for girls without obesity.

Theme II: linkages between obesity and academics

Most teachers felt students with obesity struggled more academically than students without obesity. A few teachers reported that students with obesity were at academic extremes, i.e., either highly successful or struggling; they felt obesity was sometimes linked with better academic performance, but attributed this to students with obesity having worse social lives and thus having more time to spend on academics. The proposed reasons for a relationship between obesity and academics varied, but a few themes emerged:

Obesity and academic performance: consequences of the same cause Several teachers proposed that the behaviors that led to obesity, including poor nutrition, excess screen time, insufficient sleep, and inadequate physical activity, also led to poorer academic outcomes. Two teachers thought that obesity was correlated with attention problems that caused worse academic performance; other teachers perceived similar links between obesity and unspecified emotional or behavioral problems. Several teachers also proposed that poverty was a common cause.

Obesity, self-esteem, mental health, and participation in classroom activities Most teachers perceived children with obesity to participate less in class and school activities due to lower confidence or self-esteem. One teacher said, “They don’t want to draw attention to themselves, thinking they’ve got a target painted on their head, so to speak, because they are so large.” This was echoed by another teacher, who said, “Well, when they’re in the classroom I think that they are quieter, but also I find a lot of those students are less likely to do their schoolwork as well, or to participate, to raise their hand in class. They kind of, don’t want to draw attention to themselves.”

Similarly, several teachers said that children with obesity suffered more specifically from negative emotional states or mental health problems as a result of their obesity. One teacher described this link thus, “Very few times are there truly obese children who are quote-unquote normal. You know. Participate as much as they should, and do everything that they should to the levels that they should, because they do subconsciously have that psychological baggage of some kind.”

Theme III: varied teacher treatment of students with obesity in the classroom

A large majority of teachers reported that they felt that students with obesity were treated fairly by teachers at their school. A small number of teachers said they thought their colleagues could sometimes harbor biases against students with obesity and treat them unfairly, while a small number of other teachers specifically identified unfair teacher treatment of students with obesity as a problem at their school. These teachers were careful to note that they felt teachers tried hard not to be unfair. Some of the teachers who reported no problem at their own school still thought it could be a problem elsewhere or noted that they had felt it was a problem at other schools, suggesting that school climate may play a strong role.

No teachers said that students with obesity were lazier or inherently less intelligent than their peers. However, one teacher alluded to the potential for students with obesity to have less “general endurance” than other students and another said it was possible that teachers might incorrectly attribute academic struggles of students with obesity to laziness.

Among teachers who described observing bias or acknowledged the possibility of bias, one teacher noted that it is difficult for teachers to separate out their own views from their teaching:

“Are obese students or obese people in general thought of as unintelligent? I don’t think that’s the case in my school. I don’t know if that would be true in other schools though. Because I think that teachers are people and our own beliefs and thoughts come out in what we do. When you’re teaching everything…your whole self is given to the classroom. So I think that if a teacher had a discriminatory thought, and maybe not realize it, that obese people are generally unintelligent, I think it would be possible to treat obese students differently.”

When asked if teachers treat students with obesity fairly, another teacher said,

“I think if they were being honest, if I were being honest, the answer is probably no. There’s a stigma of the students that are overweight that they might be lazy, that they don’t care for themselves as much, that they’re not as hard of workers, that they don’t have self-control. So I think those are the kind of impressions that teachers have, and I think it could bias them in terms of how they interact with them and the assumptions they make in terms of if they haven’t done their homework, why they haven’t done it, and what they might be doing outside of school, just based on their appearance.”

Theme IV: school health promotion efforts and students with obesity

Teachers described a wide range of school health promotion efforts that they felt could create positive change for students with obesity. Changing school lunch menus, turning off vending machines during the school day, and limiting the use of “junk food” for celebrations within school were commonly mentioned as positive steps, but teachers also described limited budgets for healthy school food. One teacher said, “I also think the cafeteria’s in a tough spot, like I am concerned that a lot of my kids don’t eat lunch, but…I think people need to work on funding for cafeterias and training and access and improving the cafeterias.”

Nearly half of the teachers described school programs designed to promote physical activity, such as after school running clubs or “walk to school” days. Several teachers reported that their school had a contest using pedometers in an attempt to increase physical activity. Despite this, many teachers felt their students were not given enough time to be active, whether through recess or physical education classes. Two teachers mentioned cuts that might negatively impact students’ health (health curriculum and recess) and two others discussed how gym class can now be taken online by their students.

In addition to describing these aspects of the nutrition and physical activity environment, some teachers also described the use of potentially stigmatizing health initiatives in school. Three teachers described “Biggest Loser Competitions,” i.e. where staff or students compete to lose the most amount of weight, that were held in their school. One teacher described her school’s competition thus: “We have a weight loss challenge every year, which is usually done between the staff, but this year we incorporated the students and made teams and they posted like a progress chart in the hallway and there’s a competition and it got pretty heated, so we got lots of kids involved, you know who could lose the most weight.” The teachers describing these competitions noted that many staff and students had gotten involved and felt they had been beneficial.

Discussion

Across 22 interviews with classroom teachers, we found that most teachers perceived a relationship between obesity and poorer academic performance. The proposed reasons for this perceived relationship varied and rarely included the overt stereotypes of laziness or lower intelligence typically associated with weight bias [6, 7]. Instead, most teachers, particularly teachers in middle and high schools, perceived that students with obesity had lower confidence than non-obese students and that this led to emotional problems and diminished participation in classroom and school activities, a perception we have not seen previously identified in the research literature. Many teachers also felt their students with obesity had worse school social experiences and higher risk of being bullied, and that lower self-esteem led students with obesity to withdraw from social situations.

The perceived lowered self-esteem and other emotional problems or mental health issues reported by some, but not all, teachers is consistent with findings from quantitative studies that have examined the potential relationship between obesity, self-esteem, and mental health [28–32]. The literature on this relationship remains inconclusive, but it does suggest overall that children with obesity may be more likely to have lower self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and behavioral problems compared to their peers without obesity as they grow older. However, it is unclear whether lowered self-esteem or emotional problems associated with obesity actually results in diminished classroom participation or involvement in school activities. Whether lower classroom participation by students with obesity is real or perceived, this could put these students at risk for poorer teacher-child relationships [33], and could lead to teachers underestimating the abilities of students with obesity. This is concerning given the impact of teacher expectations on student performance [34]. Future research should evaluate the interrelationships between self-esteem, classroom participation, obesity, and teacher evaluations.

Teachers’ perceptions of the relationship between obesity and bullying, as well as general social stigma, echoed what has been found in prior literature [11–15]. The worse experiences of weight stigma for girls described in this study have also been found in previous studies [15, 35, 36]. While many schools have implemented anti-bullying curricula and programs, these may not focus on the higher risk of bullying experienced by students with obesity, nor do they necessarily focus on gender differences in bullying based on physical appearance. Schools should consider the additional risk experienced by students with obesity, particularly girls, when designing strategies to reduce bullying. Future research could also explore in more detail the differential experiences of weight bias in schools by gender, and the intersection between weight bias and sexism, particularly with regards to expectations about appearance on the part of both students and school staff.

Teachers’ reports of the decline in resources for health promotion in their schools, while not directly related to academic performance, was an area of potential concern with regards to school climate. It appeared that, in the absence of access to evidence-based programs to increase physical activity and improve nutrition, many schools had been using ad hoc approaches. In particular, the weight loss competitions described could result in significant weight stigma and the use of unhealthy weight control behaviors to produce rapid weight loss; prior research has identified that “The Biggest Loser,” for example, activates weight stigma among healthy weight individuals [37] and promotes extreme weight loss techniques that are unlikely to have sustainable, health-promoting success in the general population [38]. Utilizing these weight-focused programs could also increase body image concerns among all students, irrespective of weight status, and thereby increase risk of disordered eating. Effective programs exist that promote healthy eating and physical activity habits while avoiding a stigmatizing approach or a focus solely on weight [39, 40], but these programs are not uniformly adopted. Public health practitioners and researchers should focus on better dissemination and implementation of effective, non-stigmatizing health promotion efforts. Future research could further explore the potential harmful impacts of these ad hoc wellness programs focused narrowly on weight.

Limitations

The use of a qualitative study design allowed for a more comprehensive, nuanced understanding of teachers’ perceptions of the experiences of students with obesity than may have been possible with a quantitative design using a questionnaire. However, given that this design necessitates collecting data from a smaller number of study participants, and given that this small study sample was a convenience sample in only a few distinct regions of the US with no participants from the Southern or Western US, it is not possible to generalize our findings to all US teachers in K-12 classroom settings, nor would we expect the findings to be generalizable to non-US contexts. Other investigations with different samples of teachers may yield different themes about weight stigma in schools. This qualitative inquiry was also dependent on the preconceptions of the researchers, who made assumptions in designing the interview protocol that students with obesity would likely experience weight bias from both teachers and peers, and that teachers would be likely to harbor, possibly unintentionally, biased views of heavier students. These preconceptions likely shaped our interpretation of the data, although we feel they did not prevent us from identifying other common themes from the teachers that ran counter to our preconceptions. The use of in-person interviews rather than telephone interviews for a small number of the respondents may have elicited slightly different responses due to the face-to-face nature of the interview; however, we did not identify systematic differences in the responses of teachers who were interviewed in person. Because our study aimed to elicit and describe teachers’ own reports of their experiences with regard to weight stigma and academics in schools with a qualitative approach, it is likely that we were only able to capture teachers’ perceptions of their and their colleagues’ explicit weight stigma, rather than implicit attitudes about the relationship between students’ weight and their academic ability and social experiences. Implicit attitudes could be drivers of discrimination and biased treatment of heavier students; implicit weight bias has been found to be associated with poorer patient contact among medical students [41]. Future investigations could identify strategies to explore implicit attitudes about obesity and academics in a teacher population; additionally, future investigations could explore the possible influence of teachers’ length of experience in the classroom. Additionally, we were not able to interview students about their experiences as well, limiting our findings solely to perceptions from teachers. Future research should carefully explore students’ perceptions of the relationship between the school environment, academics, teachers, and opportunities for students with obesity.

Conclusions

Taken together, these findings suggest that these teachers perceive schools to be difficult environments for many students with obesity, and that their academic achievement may suffer as a result. Although teachers in this study almost never reported that they or their colleagues held biased attitudes towards students with obesity, the majority of teachers in this study did suggest that they believe obesity is associated with reduced school performance despite evidence to the contrary [17–21]. This suggests that potential interventions to reduce weight bias among teachers, which currently focus on reducing classic stereotypes about individuals with obesity, may need to go further and address well-intended, but potentially damaging, perceptions about the confidence, participation, and academic performance of students with obesity.

References

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM (2014) Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA 311(8):806–814. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.732

Berenson GS, Srnivasan SR (2005) Cardiovascular risk factors in youth with implications for aging: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Neurobiol Aging 26(3):303–307. doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.05.009

Guo SS, Wu W, Chumlea WC, Roche AF (2002) Predicting overweight and obesity in adulthood from body mass index values in childhood and adolescence. Am J Clin Nutr 76:653–658

Must A, Strauss RS (1999) Risks and consequences of childhood and adolescent obesity. Int J Obes 23(suppl 2):S2–S11. doi:10.1038/sj/ijo/0800852

Figueroa-Colon R, Franklin FA, Lee JY, Aldridge R, Alexander L (1997) Prevalence of obesity with increased blood pressure in elementary school-aged children. South Med J 90:806–813. doi:10.1097/00007611-199708000-00007

Puhl RM, Heuer CA (2009) The stigma of obesity: a review and update. Obesity 17:941–964. doi:10.1038/oby.2008.636 (Epub 2009 Jan 22)

Puhl R, Brownell KD (2003) Psychosocial origins of obesity stigma: toward changing a powerful and pervasive bias. Obes Rev 4:213–227. doi:10.1046/j.1467-789x.2003.00122.x

Andreyeva T, Puhl RM, Brownell KD (2008) Changes in perceived weight discrimination among Americans: 1995–1996 through 2004–2006. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16:1129–1134. doi:10.1038/oby.2008.35 (Epub 2008 Feb 28)

Neumark-Sztainer D, Falkner N, Story M, Perry C, Hannan PJ, Mulert S (2002) Weight-teasing among adolescents: correlations with weight status and disordered eating behaviors. Int J Obes 26:123–131

Haines J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Eisenberg ME, Hannan PJ (2006) Weight teasing and disordered eating behaviors in adolescents: longitudinal findings from Project EAT (Eating Among Teens). Pediatrics 117(2):e209–e215. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0801853

Libbey HP, Story MT, Neumark-Sztainer DR, Boutelle KN (2008) Teasing, disordered eating behaviors, and psychological morbidities among overweight adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring). 16(Suppl 2):S24–S29. doi:10.1038/oby.2008.455

Crosnoe R (2007) Gender, obesity, and education. Sociol Educ 80:241–260. doi:10.1177/003804070708000303

Gortmaker SL, Must A, Perrin JM, Sobol AM, Dietz WH (1993) Social and economic consequences of overweight in adolescence and young childhood. N Engl J Med 329:1008–1012. doi:10.1056/NEJM199309303291406

Hayden-Wade HA, Stein RI, Ghaderi A, Saelens BE, Zabinski MF, DE Wilfley (2005) Prevalence, characteristics, and correlates of teasing experiences among overweight children vs. non-overweight peers. Obes Res. doi:10.1038/oby.2005.167

Griffiths LJ, Wolke D, Page AS, Horwood JP (2006) Obesity and bullying: different effects of boys and girls. Arch Dis Child 91:121–125. doi:10.1136/adc.2005.072314

Shore SM, Sachs ML, Lidicker JR, Brett SN, Wright AR, Libonati JR (2008) Decreased scholastic achievement in overweight middle school students. Obesity 16:1535–1538. doi:10.1038/oby.2008.254

Kenney EL, Gortmaker SL, Davison KK, Austin SB (2015) The academic penalty for gaining weight: a longitudinal, change-in-change analysis of BMI and perceived academic ability in middle school students. Int J Obes (Lond). 39(9):1408–1413. doi:10.1038/ijo.2015.88 (Epub 2015 May 18)

Huang TTK, Goran MI, Spruijt-Metz D (2006) Associations of adiposity with measured and self-reported academic performance in early adolescence. Obesity 14:1839–1845. doi:10.1038/oby.2006.212

MacCann C, Roberts RD (2013) Just as smart but not as successful: obese students obtain lower school grades but equivalent test scores to nonobese students. Int J Obes 37:40–46. doi:10.1038/ijo.2012.47 (Epub 2012 Apr 24)

Kaestner R, Grossman M (2009) Effects of weight on children’s achievement. Econ Educ Rev 28:651–661. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2009.03.002

Veldwijk J, Fries MCE, Bemelmans WJE, Haveman-Nies A, Smit HA, Koppelman GH, Wijga AH (2012) Overweight and school performance among primary school children: the PIAMA birth cohort study. Obesity 20:590–596. doi:10.1038/oby.2011.327

Datar A, Sturm R, Magnabosco JL (2004) Childhood overweight and academic performance: national study of kindergartners and first-graders. Obesity 12:58–68. doi:10.1038/oby.2004.9

O’Brien KS, Hunter JA, Banks M (2007) Implicit anti-fat bias in physical educators: physical attributes, ideology and socialization. Int J Obes 31:308–314. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0803398

Greenleaf C, Weiller K (2005) Perceptions of youth obesity among physical educators. Soc Psychol Educ 8:407–423. doi:10.1007/s11218-005-0662-9

Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Harris T (1999) Beliefs and attitudes about obesity among teachers and school health care providers working with adolescents. J Nutr Ed Behav 31:3–9. doi:10.1016/S0022-3182(99)70378-X

Borkan J (1999) Immersion/crystallisation. In: Crabtree B, Miller W (eds) Doing qualitative research. Sage, Thousand Oaks, pp 179–194

National Center for Education Statistics (2015) Fast facts: teacher trends: what are the current trends in the teaching profession? http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=28. Accessed 6 Mar 2015

Russell-Mayhew S, McVey G, Bardick A, Ireland A (2012) Mental health, wellness, and childhood overweight/obesity. J Obesity. doi:10.1155/2012/281801 (Article ID 281801)

Strauss RS (2000) Childhood obesity and self-esteem. Pediatrics. doi:10.1542/peds.105.1.e15

Goldfield GS, Moore C, Henderson K, Buchholz A, Obeid N, Flament MF (2010) Body dissatisfaction, dietary restraint, depression, and weight status in adolescent. J Sch Health 80:186–192. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00485.x

Anderson SE, Cohen P, Naumova EN, Must A (2006) Association of depression and anxiety disorders with weight change in a prospective community-based study of children followed up into adulthood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 160:285–291. doi:10.1001/archpedi.160.3.285

Lumeng JC, Gannon K, Cabral HJ, Frank DA, Zuckerman B (2003) Association between clinically meaningful behavior problems and overweight in children. Pediatrics 112:1138–1145. doi:10.1542/peds.112.5.1138

Rudasill KM, Rimm-Kaufman SE (2009) Teacher-child relationship quality: the roles of child temperament and teacher-child interactions. Early Child Res Q 24:107–120. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2008.12.003

Hinnant JB, O’Brien M, Ghazarian SR (2009) The longitudinal relations of teacher expectations to achievement in the early school years. J Educ Psychol 101:662–670. doi:10.1037/a0014306

Tiggemann M, Rothblum ED (1988) Gender differences in social consequences of perceived overweight in the United States and Australia. Sex Roles 18:75–86. doi:10.1007/BF00288018

Israel AC, Ivanova MY (2002) Global and dimension self-esteem in preadolescent and early adolescent children who are overweight: age and gender differences. Int J Eat Disord 31:424–429. doi:10.1002/eat.10048

Domoff SE, Hinman NG, Koball AM, Storfer-Isser A, Carhart VL, Baik KD, Carels RA (2012) The effects of reality television on weight bias: an examination of The Biggest Loser. Obesity (Silver Spring). 20(5):993–998. doi:10.1038/oby.2011.378 (Epub 2012 Jan 12)

Klos LA, Greenleaf C, Paly N, Kessler MM, Shoemaker CG, Suchla EA (2015) Losing weight on reality TV: a content analysis of the weight loss behaviors and practices portrayed on The Biggest Loser. J Health Commun. 20(6):639–646. doi:10.1080/10810730.2014.965371 (Epub 2015 Apr 24)

Austin SB, Field AE, Wiecha J, Peterson KE, Gortmaker SG (2005) The impact of a school-based obesity prevention trial on disordered weight-control behaviors in early adolescent girls. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 159(3):225–230. doi:10.1001/archpedi.159.3.225

Austin SB, Kim J, Wiecha J, Troped PJ, Feldman HA, Peterson KE (2007) School-based overweight preventive intervention lowers incidence of disordered weight-control behaviors in early adolescent girls. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 161(9):865–869. doi:10.1001/archpedi.161.9.865

Phelan SM, Puhl RM, Burke SE, Hardeman R, Dovidio JF, Nelson DB, Przedworski J, Burgess DJ, Perry S, Yeazel MW, van Ryn M (2015) The mixed impact of medical school on medical students’ implicit and explicit weight bias. Med Educ 49(10):983–992. doi:10.1111/medu.12770

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders, Ellen Feldberg Gordon Fund for Eating Disorders Research. S. Criss was also supported by predoctoral training Grants from NIH Award # 3R25CA057711, the Initiative to Maximize Student Diversity Award # GM055353-13; and Maternal and Child Health Bureau Award #T03MC07648.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Human subjects approval statement

This study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board in the Office of Human Research Administration, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kenney, E.L., Redman, M.T., Criss, S. et al. Are K-12 school environments harming students with obesity? A qualitative study of classroom teachers. Eat Weight Disord 22, 141–152 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0268-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0268-6