Abstract

Purpose of the review

Gaps exist between the research knowledge base and clinical practices pertaining to the use of antipsychotics in delirium. We reviewed 19 major randomized studies on the use of antipsychotics in non-substance-related delirium to understand factors contributing to this gap.

Recent findings

Based on limited literature, antipsychotics are not effective in treating delirium in patients who are mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients and those in palliative care, but they may be effective in preventing delirium in high-risk patients after elective surgery. The literature on the use of antipsychotics for delirium in general hospital patients is less clear.

Summary

Delirium is a complex and heterogeneous syndrome and is influenced by several individual and clinical factors, which make researching its pharmacological treatment very difficult. Furthermore, heterogeneity of the studies is a barrier to reliable meta-analyses. Until methodologically sound literature pertinent to specific patient populations and clinical scenarios accumulates, we should use both the research literature and clinical expertise to formulate practice guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Delirium is a syndromal manifestation of cerebral dysfunction resulting from a range of diverse reasons that are pathological in nature or disruptive to the biochemical processes of the body. It is characterized by a disturbance in attention and awareness that develops over a short period of time, tends to fluctuate over the course of the day, and is accompanied by at least one other disturbance in cognition involving memory, orientation, language, visuospatial ability, or perception [1]. The DSM-5 suggests five diagnostic specifiers namely substance intoxication delirium, substance withdrawal delirium, medication-induced delirium, delirium due to another medical condition, and delirium due to multiple etiologies. Patients with delirium may be in a state of psychomotor agitation (hyperactive delirium), lethargy and stupor (hypoactive delirium), or fluctuate between these two states (mixed delirium). Delusions and hallucinations are not required diagnostic features of delirium but often occur in its mixed subtype [2•]. The prevalence of delirium varies dramatically based on the patient population and the method of assessment and ranges between 10–31% in general hospital settings [3], 30–80% [4] in critical care settings, and 13–88% in palliative care settings [5].

The standard prevention and management strategies for delirium incorporate treating the underlying cause(s), offering supportive and non-pharmacological interventions, and using medications to control acute symptoms. Medications used for symptomatic management of delirium in diverse clinical settings include antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, antiepileptics, and melatonin-regulating agents. The use of these medications in delirium is off-label as none has a formal regulatory approval.

Historically, haloperidol was the preferred medication for symptomatic management of non-substance withdrawal delirium due to its known efficacy for psychosis, better side effect profile than benzodiazepines and low-potency antipsychotics, and the ease of administration because of availability in both oral and parenteral forms [6]. With the advent of second-generation antipsychotics, they were studied for delirium as an alternative to haloperidol. Despite limited data on their efficacy, haloperidol and the relatively older second-generation antipsychotics including risperidone, olanzapine, and quetiapine are now among the commonly used antipsychotics for symptomatic management of non-substance withdrawal delirium [7, 8••].

The use of antipsychotics in non-substance-related delirium remains a matter of debate with several questions still unanswered [8••, 9]. Over the last few years, some studies and meta-analyses have raised doubts about the efficacy of antipsychotics in delirium. For example, Neufeld et al. [10] systematically reviewed the literature published between 1988 and 2013 and identified 19 studies that met their inclusion criteria. They found that antipsychotic use was not associated with change in delirium duration, severity, or hospital or intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay. Similarly, the current clinical practice guidelines on management of delirium in adult ICU patients noted that there was no published evidence to support that haloperidol reduced duration of delirium in ICU patients, and only one small study suggested quetiapine may reduce the duration [11]. In contrast, other meta-analyses have found that antipsychotics are better than placebo for prevention and treatment of delirium [12, 13]. In practice, antipsychotics are still used for delirium in diverse clinical settings and are often recommended in institutional guidelines [14]. Antipsychotics are the most studied agents to prevent and treat delirium, but it is difficult to translate research findings into clinical practice [8••]. We undertook this review to better understand this dilemma. We briefly describe the randomized-controlled studies on the use of antipsychotics for treatment or prevention of delirium as well as the randomized studies that compared antipsychotics without a control group and then highlight factors based on these studies that make it difficult to draw reliable clinical guidance from their findings.

Treatment

Use of antipsychotics to treat or prevent delirium

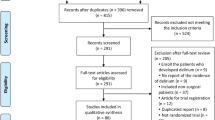

We searched PubMed for English literature from last 10 years using search terms “antipsychotic” and “delirium.” From the titles of the search results, we identified several studies and meta-analyses of interest and reviewed their abstracts. We also reviewed the reference lists of several recent meta-analyses. We identified 19 randomized studies on the use of antipsychotics in delirium—five studies compared antipsychotics with placebo for treatment of delirium [15–19], six studies compared antipsychotics with placebo to prevent delirium [20–25], and eight studies compared various antipsychotics with each other without a control group [26–33].

Studies on the use of antipsychotics for treatment of delirium

We identified five randomized-controlled studies that compared antipsychotics with placebo for the treatment of delirium (Table 1) [15–19]. Two of these studies were conducted on mechanically ventilated ICU patients with haloperidol as the active agent in one [18] and haloperidol and ziprasidone as active agents in the other [17]. In both these studies, active agents did not offer benefit over placebo in terms of number of days in delirium, number of days without delirium, resolution of delirium, the length of stay in the ICU, or mortality. Another ICU study had a mixed patient population, but over 70% of the patients were intubated upon admission to the ICU [16]. In this study [16], the quetiapine group fared better than the placebo group in terms of delirium-free days and time to resolution of delirium, but the duration of ICU stay was similar for both groups. One study included patients from medical and surgical wards [19]. Forty-five percent of the patients had undergone surgery, mostly for orthopedic reasons. Patients in the quetiapine group recovered significantly faster than patients in the placebo group in terms of delirium severity. Lastly, one study was conducted with palliative care patients [15]. Most patients had the diagnosis of cancer. At the 3-day study end, the delirium symptom scores were significantly higher in patients receiving risperidone or haloperidol than patients receiving placebo. Overall, these data suggest that antipsychotics are not effective in treating delirium in patients who are mechanically ventilated ICU patients and in palliative care, but may be effective in treating delirium in general medical and surgical patients (Table 1).

Randomized-controlled studies on the use of antipsychotics to prevent delirium

We identified six studies that compared antipsychotics with placebo to prevent delirium in high-risk patients [20–25] (Table 2). Two studies used haloperidol [21] and olanzapine [23], respectively, as active agents for prevention of delirium after elective orthopedic surgery. Although the active agents offered significant benefits over the placebo on many measures of delirium, these benefits were not consistent across the studies. The incidence of delirium in the study using haloperidol was comparable to placebo, but it was significantly lower than placebo in the study using olanzapine. In contrast, delirium duration was briefer with haloperidol but longer with olanzapine, in comparison with placebo. A lower incidence of delirium was also noted in patients who received prophylactic haloperidol after gastrointestinal surgery than those who received placebo [22]. In another study of patients who had undergone cardiac surgery, risperidone significantly decreased the incidence of delirium compared with placebo [24]. In another study, elderly ICU patients (> 85 years age) who had undergone non-cardiac surgery were randomized to receive a small prophylactic dose of haloperidol or placebo over the initial 12-h after surgery [25]. If delirium developed, it was handled with non-pharmacological interventions first and open-label haloperidol was reserved for severe agitation. The haloperidol group fared better than the placebo group on all measures of delirium used in the study. Finally, in one study, patients who developed subsyndromal delirium after on-pump cardiac surgery, the incidence of delirium was significantly lower with risperidone than placebo [20]. Overall, these data suggest that haloperidol, olanzapine, or risperidone prophylaxis benefit postoperative patients in diverse surgical situations (Table 2).

Randomized studies without a control group comparing various antipsychotics in delirium

We included eight randomized studies that compared two or more antipsychotics with each other without a placebo control group [26–33] (Table 3). Antipsychotics researched in these studies included amisulpride, chlorpromazine, haloperidol, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone. The patient populations in these studies were much more diverse and mixed than the patient populations in the placebo-controlled delirium treatment and prophylaxis studies we previously summarized. Drug dosing in these studies was flexible that allowed adjusting the study drugs on as-needed basis. Additionally, the as-needed use of parenteral haloperidol or a benzodiazepine was allowed in some studies. In all of these studies, delirium severity improved over the course of the study without any significant differences between the antipsychotics in any given study. One study that had a lorazepam treatment group as well reported worsening of delirium in the lorazepam group [26] (Table 3).

Factors to consider when drawing clinical guidance from the literature

We identified several interrelated factors that should be considered when interpreting the findings of the abovementioned studies from a clinical perspective.

The complexity of delirium and its impact on research findings

Delirium is a heterogeneous syndromal expression of diverse diseases and clinical scenarios, often occurs in patients who have multiple pathologies and are on multiple medications, and is influenced by individual factors such as age, degree of morbidity, and history of alcohol use. Because clinical complexity is integral to most cases of non-substance-related delirium, we cannot research it in a population free of confounding risk factors. Furthermore, delirium is a dynamic process. Its severity, course, duration, and outcome depend upon the causative conditions and their treatment. These factors are very difficult to control in research settings and would impact the study findings [34••]. Current literature suggests that antipsychotics are not better than placebo when delirium is severe and complicated (e.g., in the mechanically ventilated ICU patients) or when its cause is untreatable (e.g., in the palliative care patients), but they may be better than placebo in the relatively less sick general hospital population and after elective surgeries.

The impact of use of as-needed medications

Due to obvious clinical reasons, the placebo-controlled studies of delirium permit the use of as-needed medications, which usually is an antipsychotic, a benzodiazepine, or both. When patients in the placebo group receive as-needed medication(s), it narrows the efficacy gap between the antipsychotic and the placebo groups. For example, in the study by Page et al. [18], haloperidol did not offer benefit over the placebo. However, in this study, 21% of the patients in the placebo group received as-needed haloperidol (versus 8% in the haloperidol group), and the duration of as-needed treatment was significantly longer in the placebo group versus the haloperidol group. Similarly, in the study by Devlin et al. [16], placebo-treated patients required significantly more days of as-needed haloperidol (3–8 days) and a sedative agent (propofol or a benzodiazepine; 1–9 days) than patients treated with quetiapine (2–4 days and 0–3 days, respectively).

The studies may not capture matters of clinical relevance

Current studies on the use of antipsychotics in delirium do not capture a few important clinical aspects. Anecdotally, antipsychotics may help decrease agitation, distress, and combative behavior, but not necessarily and immediately the other symptoms of delirium. As delirium scales are structured to capture broad symptoms [35•], the overall score may not reflect improvement in a few symptoms. The decreased incidence and severity of delirium with the prophylactic use of antipsychotics versus the placebo in the high-risk patients and those with subsyndromal delirium may have been due to decreased agitation and consequent decreased disruption in care, but current literature does not specifically inform us in this regard [20, 36]. Delirium is distressing for the patient and his/her family, so is often also disruptive to clinical care, but current research on the use of antipsychotics in delirium does not capture these aspects as well.

Statistical significance (or lack thereof) may not reflect clinical significance

“Statistical significance” is used to minimize “chance” findings. Several factors drive the “by chance” occurrence(s) and the complexity rises as the number of confounding factors rises. A small sample size, presence of outliers, and how drop-outs are statistically managed can diminish or exaggerate statistical findings further. While statistical significance is important to identify the likelihood that a result occurred by chance, it may not always accurately reflect clinical significance. For example, in the placebo-controlled study by Devlin et al. [16], there was no statistically significant difference between the treatment groups at baseline, but clinically, the placebo-treated group seemed sicker than the quetiapine-treated group with intubated patients at the start of the study being 89 versus 72% and patients coming from another hospital being 44 versus 11%, respectively. Similarly, in the study by Girard et al. [17], the percent of patients who required as-needed haloperidol (total dose) in the haloperidol, ziprasidone, and placebo groups was 17% (4.5 mg), 30% (10 mg), and 39% (12.5 mg), respectively. One patient (3%) in the haloperidol group, two patients (7%) in the ziprasidone group, and four patients (11%) in the placebo group were administered additional second-generation antipsychotics. None of these differences were statistically significant, but clinically these are meaningful differences that may have impacted the research findings.

Heterogeneity of studies prevents reliable meta-analyses

Current literature on the use of antipsychotics in delirium is heterogeneous in terms of the patient population, nature, and severity of the condition(s) causing delirium, clinical setting, methodology to monitor delirium, doses of the study antipsychotics, allowance of as-needed use of medications, duration of monitoring, and measures of patient outcome. Meta-analyses can provide conflicting results depending upon the studies included/excluded. For example, Fok et al. reviewed the literature on the prophylactic use of antipsychotics in delirium and based on meta-analysis of six studies concluded that antipsychotics reduced the incidence of delirium in several surgical settings, predominantly orthopedic [12]. In contrast, Neufeld et al. performed a meta-analysis of seven studies (five of which were included in the meta-analysis by Fok et al. [12]) and concluded that prophylactic use of antipsychotics did not prevent delirium [10]. Both authors observed heterogeneity between studies. The negative findings by Neufeld et al. [10] seemingly were driven by a study that used a historical no-treatment comparison group [37]. Another similar study has observed mostly positive findings [36], but its data was not included in some of the analysis by Neufeld et al. [10]. This highlights that the findings of meta-analyses on this topic are not consistent and cannot be used reliably for clinical guidance.

Importance of studies comparing various antipsychotics for delirium

Studies that compare efficacy of antipsychotics in delirium without a placebo control group have a major limitation—there is no control group. The limitation is particularly true considering there is no proven effective antipsychotic for delirium that can be used as a comparator. Antipsychotics tend to get grouped together because of their shared approved indications. But in reality, they differ from each other in terms of their neurochemical profile and may differ from each other dramatically when used for other conditions (e.g., in Parkinson’s disease psychosis [38]). Well-designed studies comparing antipsychotics in delirium without placebo will help us better define the possible benefits and side effects of antipsychotics in delirium relative to each other.

Discussion

The current literature on the use of antipsychotics in delirium is too heterogeneous and limited to provide a reliable clinical guidance. Limited literature suggests that antipsychotics are not effective in treating delirium in patients who are mechanically ventilated ICU patients and those receiving palliative care, but they may have a role in managing delirium in general hospital patients. All the studies we reviewed [20–25] and several meta-analysis [12, 39, 40] support the prophylactic use of antipsychotics in high-risk surgical patients, but one meta-analysis [10] has concluded otherwise. So far, the antipsychotics that have consistent (but still limited) evidence for managing or preventing non-substance-related delirium include haloperidol, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone. These data cannot be generalized to other antipsychotics or to substance-related delirium.

Delirium is best managed through a multidisciplinary team approach that includes the patient’s family. Antipsychotics should only be considered after non-pharmacological interventions have been offered, and these interventions should continue during the antipsychotic treatment. Symptomatic management of delirium should not draw attention away from investigating and treating the underlying cause(s) of delirium. The decision to use an antipsychotic and the choice and dosing of the antipsychotic should be made on a case-by-case basis. The effectiveness of antipsychotic treatment should be monitored systematically, and the antipsychotic should be withdrawn or substituted if it is ineffective after a few days of treatment. We do not advise continued use of antipsychotics to manage delirium when it is protracted because of a complex etiology or comorbid dementia.

It is essential to monitor antipsychotics for their side effects. From among the four antipsychotics under discussion, haloperidol and risperidone are more likely to cause extrapyramidal side effects and olanzapine and quetiapine are more likely to cause sedation. Much lower doses should be used in elderly patients, as they are prone to extrapyramidal side effects even with second-generation antipsychotics [41, 42]. Haloperidol should not be used in patients with Parkinsonism, and risperidone should be used cautiously in very small doses [41]. Risperidone and to a lesser extent olanzapine and quetiapine may also cause a drop in blood pressure. Olanzapine should be used cautiously in the elderly in view of the few case reports suggesting it can cause delirium in these patients [43–45]. We must also be mindful of warnings from the regulatory agencies about the use of antipsychotics in patients with dementia and the increased risk of QTc prolongation in patients with multi-morbidity taking multiple medications associated with QTc prolongation [46, 47]. The rare likelihood of neuroleptic malignant syndrome should also be kept in mind. It is quite concerning that antipsychotics are continued in significant number of patients after delirium has resolved, and in some cases they are continued even after patient’s discharge from the hospital [48•, 49]. Antipsychotics initiated for delirium must be discontinued as soon as delirium resolves.

Researching the pharmacological prevention and treatment of delirium is very difficult due to the heterogeneity, different types and variable course of delirium, absence of biological markers to assess and monitor delirium, numerous confounding factors, and high drop-out rates. A proper placebo-controlled study is essentially impossible, because we cannot withhold a medication considered clinically effective from research patients who are in acute distress or at risk of hurting themselves or others [50••]. Using the study, antipsychotic (instead of a different antipsychotic) as the as-needed medication in the active arm as well as the placebo arm can help simplify this aspect of the research. Defining the study populations narrowly in terms of pathologies and severity, setting guidelines on which tools to use to screen and monitor for delirium, and setting robust statistical methods as a standard can help generate sound and homogenous research. Furthermore, broadening the research to the clinically pertinent aspects of delirium we discussed earlier can help better understand the possible utility of antipsychotics in delirium. Several important questions pertaining to the pharmacological prevention and management of delirium need to be answered to inform us clinically [8••].

A clinical guidance that is far removed from real-life clinical practices is likely to be ignored by clinicians. Even though we did not specifically explore clinician-related factors that may be contributing to gaps between knowledge and practice, we have anecdotally observed a tremendous need to improve the knowledge base and clinical practices pertaining to the use of antipsychotics in delirium. In some scenarios, antipsychotics may be over-utilized at the expense of non-pharmacological interventions, they may get over-used in dosage and duration, the possible beneficial effect of relatively well-studied antipsychotics may get generalized to antipsychotics that have not been well-studied, and their effectiveness and side effects may be difficult to monitor in view of the fluctuations in the patient’s clinical status. These are important clinical aspects to research to bridge the gap between knowledge and clinical practices.

Our review should be read keeping in mind its limitations. We only focused on randomized studies. We mentioned two major studies that used historical control groups [36, 37] and several recent meta-analyses [10, 12, 13, 39, 40] but might have missed other studies. We did not elaborate on the strengths and weaknesses of individual studies because that was beyond the scope of this paper. We do selectively and conservatively recommend use of antipsychotics in delirium. This approach could have biased us to interpret research data to support our clinical point of view. Lastly, our review pertains to adults with delirium. Literature pertaining to the use of antipsychotics in children and adolescents with delirium is quite limited [51] and cannot be integrated with the literature from the adult population.

Conclusion

Current literature is too limited to reliably support or reject the use of antipsychotics in delirium. Until methodologically sound research pertinent to specific patient populations and clinical scenarios accumulates, we should use both the research literature and clinical expertise to formulate the best practice guidelines. Professional associations representing clinicians who provide care to patients with delirium can work together to provide clinical guidance that balances the limited research literature with clinical expertise. These associations can also provide guidance on the methodology of future research on prevention and treatment of delirium to help generate homogenous research that is suitable for meta-analyses and can be translated into clinical practice more consistently.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

• Meagher DJ, Leonard M, Donnelly S, Conroy M, Adamis D, Trzepacz PT. A longitudinal study of motor subtypes in delirium: relationship with other phenomenology, etiology, medication exposure and prognosis. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(6):395–403. An excellent study on the motor subtypes of delirium in palliative care patients. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.06.001.

Ryan DJ, O'Regan NA, Caoimh RO, Clare J, O'Connor M, Leonard M, et al. Delirium in an adult acute hospital population: predictors, prevalence and detection. BMJ Open. 2013;7:3(1).

Salluh JI, Soares M, Teles JM, Ceraso D, Raimondi N, Nava VS, et al. Delirium epidemiology in critical care (DECCA): an international study. Crit Care. 2010;14(6):R210. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc9333.

Hosie A, Davidson PM, Agar M, Sanderson CR, Phillips J. Delirium prevalence, incidence, and implications for screening in specialist palliative care inpatient settings: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2013;27(6):486–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216312457214.

Jacobi J, Fraser GL, Coursin DB, Riker RR, Fontaine D, Wittbrodt ET, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(1):119–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-200201000-00020.

Thom RP, Mock CK, Teslyar P. Delirium in hospitalized patients: risks and benefits of antipsychotics. Cleve Clin J Med. 2017;84(8):616–22. https://doi.org/10.3949/ccjm.84a.16077.

•• Meagher DJ, McLoughlin L, Leonard M, Hannon N, Dunne C, O'Regan N. What do we really know about the treatment of delirium with antipsychotics? Ten key issues for delirium pharmacotherapy. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(12):1223–1238. The publication highlights very important questions that need to be addressed with regards to the use of antipsychotics in delirium. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2012.09.008.

Meagher D, Agar MR, Teodorczuk A. Debate article: Antipsychotic medications are clinically useful for the treatment of delirium. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017; 30.

Neufeld KJ, Yue J, Robinson TN, Inouye SK, Needham DM. Antipsychotic medication for prevention and treatment of delirium in hospitalized adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(4):705–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14076.

Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, Ely EW, Gelinas C, Dasta JF, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):263–306. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182783b72.

Fok MC, Sepehry AA, Frisch L, Sztramko R, van der Burg BL B, Vochteloo AJ, et al. Do antipsychotics prevent postoperative delirium? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(4):333–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4240.

Kishi T, Hirota T, Matsunaga S, Iwata N. Antipsychotic medications for the treatment of delirium: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(7):767–74. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2015-311049.

Michaud L, Bula C, Berney A, Camus V, Voellinger R, Stiefel F, et al. Delirium: guidelines for general hospitals. J Psychosom Res. 2007;62(3):371–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.10.004.

Agar MR, Lawlor PG, Quinn S, Draper B, Caplan GA, Rowett D, et al. Efficacy of oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo for symptoms of delirium among patients in palliative care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):34–42. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7491.

Devlin JW, Roberts RJ, Fong JJ, Skrobik Y, Riker RR, Hill NS, et al. Efficacy and safety of quetiapine in critically ill patients with delirium: a prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):419–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b9e302.

Girard TD, Pandharipande PP, Carson SS, Schmidt GA, Wright PE, Canonico AE, et al. Feasibility, efficacy, and safety of antipsychotics for intensive care unit delirium: the MIND randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):428–37. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181c58715.

Page VJ, Ely EW, Gates S, Zhao XB, Alce T, Shintani A, et al. Effect of intravenous haloperidol on the duration of delirium and coma in critically ill patients (Hope-ICU): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(7):515–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70166-8.

Tahir TA, Eeles E, Karapareddy V, Muthuvelu P, Chapple S, Phillips B, et al. A randomized controlled trial of quetiapine versus placebo in the treatment of delirium. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69(5):485–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.05.006.

Hakim SM, Othman AI, Naoum DO. Early treatment with risperidone for subsyndromal delirium after on-pump cardiac surgery in the elderly: a randomized trial. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(5):987–97. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e31825153cc.

Kalisvaart KJ, de Jonghe JF, Bogaards MJ, Vreeswijk R, Egberts TC, Burger BJ, et al. Haloperidol prophylaxis for elderly hip-surgery patients at risk for delirium: a randomized placebo-controlled study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(10):1658–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53503.x.

Kaneko T. Prophylactic consecutive administration of haloperidol can reduce the occurrence of postoperative delirium in gastrointestinal surgery. Yonago Acta Med. 1999;42:179–84.

Larsen KA, Kelly SE, Stern TA, Bode RH Jr, Price LL, Hunter DJ, et al. Administration of olanzapine to prevent postoperative delirium in elderly joint-replacement patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Psychosomatics. 2010;51(5):409–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(10)70723-4.

Prakanrattana U, Prapaitrakool S. Efficacy of risperidone for prevention of postoperative delirium in cardiac surgery. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2007;35(5):714–9.

Wang W, Li HL, Wang DX, Zhu X, Li SL, Yao GQ, et al. Haloperidol prophylaxis decreases delirium incidence in elderly patients after noncardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(3):731–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182376e4f.

Breitbart W, Marotta R, Platt MM, Weisman H, Derevenco M, Grau C, et al. A double-blind trial of haloperidol, chlorpromazine, and lorazepam in the treatment of delirium in hospitalized AIDS patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(2):231–7. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.153.2.231.

Grover S, Kumar V, Chakrabarti S. Comparative efficacy study of haloperidol, olanzapine and risperidone in delirium. J Psychosom Res. 2011;71(4):277–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.01.019.

Han CS, Kim YK. A double-blind trial of risperidone and haloperidol for the treatment of delirium. Psychosomatics. 2004;45(4):297–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-3182(04)70170-X.

Kim SW, Yoo JA, Lee SY, Kim SY, Bae KY, Yang SJ, et al. Risperidone versus olanzapine for the treatment of delirium. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(4):298–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.1117.

Lee KU, Won WY, Lee HK, Kweon YS, Lee CT, Pae CU, et al. Amisulpride versus quetiapine for the treatment of delirium: a randomized, open prospective study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(6):311–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004850-200511000-00005.

Maneeton B, Maneeton N, Srisurapanont M, Chittawatanarat K. Quetiapine versus haloperidol in the treatment of delirium: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2013;7:657–67. https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S45575.

Skrobik YK, Bergeron N, Dumont M, Gottfried SB. Olanzapine vs haloperidol: treating delirium in a critical care setting. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):444–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-003-2117-0.

Yoon HJ, Park KM, Choi WJ, Choi SH, Park JY, Kim JJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of haloperidol versus atypical antipsychotic medications in the treatment of delirium. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):240. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-240.

•• Farewell D, Tahir TA, Bisson J. Statistical methods in randomised controlled trials for delirium. J Psychosom Res. 2012;73(3):197–204. The publication discusses important statistical aspects of randomized-controlled trials on delirium. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.06.002.

• Adamis D, Sharma N, Whelan PJ, Macdonald AJ. Delirium scales: a review of current evidence. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(5):543–555. A detailed review of evidence on delirium scales used clinically and in research. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860903421011.

van den Boogaard M, Schoonhoven L, van A T, van der Hoeven JG, Pickkers P. Haloperidol prophylaxis in critically ill patients with a high risk for delirium. Crit Care. 2013;17(1):R9. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc11933.

Vochteloo AJ, Moerman S, van der Burg BL, de B M, de Vries MR, Niesten DD, et al. Delirium risk screening and haloperidol prophylaxis program in hip fracture patients is a helpful tool in identifying high-risk patients, but does not reduce the incidence of delirium. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11(1):39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-11-39.

Hasnain M. Psychosis in Parkinson's disease: therapeutic options. Drugs Today (Barc ). 2011;47(5):353–67. https://doi.org/10.1358/dot.2011.47.5.1584113.

Hirota T, Kishi T. Prophylactic antipsychotic use for postoperative delirium: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(12):e1136–44. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.13r08512.

Teslyar P, Stock VM, Wilk CM, Camsari U, Ehrenreich MJ, Himelhoch S. Prophylaxis with antipsychotic medication reduces the risk of post-operative delirium in elderly patients: a meta-analysis. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(2):124–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2012.12.004.

Hasnain M, Vieweg WV, Baron MS, Beatty-Brooks M, Fernandez A, Pandurangi AK. Pharmacological management of psychosis in elderly patients with parkinsonism. Am J Med. 2009;122(7):614–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.01.025.

Rochon PA, Stukel TA, Sykora K, Gill S, Garfinkel S, Anderson GM, et al. Atypical antipsychotics and parkinsonism. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(16):1882–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.16.1882.

Lim CJ, Trevino C, Tampi RR. Can olanzapine cause delirium in the elderly? Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40(1):135–8. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1G318.

Park JI. Delirium associated with olanzapine use in the elderly. Psychogeriatrics. 2017;17(2):142–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12195.

Sharma RC, Aggarwal A. Delirium associated with olanzapine therapy in an elderly male with bipolar affective disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2010;7(2):153–4. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2010.7.2.153.

Hasnain M, Vieweg WV. QTc interval prolongation and torsade de pointes associated with second-generation antipsychotics and antidepressants: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(10):887–920. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-014-0196-9.

Vieweg WV, Wood MA, Fernandez A, Beatty-Brooks M, Hasnain M, Pandurangi AK. Proarrhythmic risk with antipsychotic and antidepressant drugs: implications in the elderly. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(12):997–1012. https://doi.org/10.2165/11318880-000000000-00000.

• Flurie RW, Gonzales JP, Tata AL, Millstein LS, Gulati M. Hospital delirium treatment: continuation of antipsychotic therapy from the intensive care unit to discharge. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(23 Suppl 3):S133–S139. The study identifies that antipsychotics initiated for delirium are continued in many patients even after the resolution of delirium. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp150474.

Jasiak KD, Middleton EA, Camamo JM, Erstad BL, Snyder LS, Huckleberry YC. Evaluation of discontinuation of atypical antipsychotics prescribed for ICU delirium. J Pharm Pract. 2013;26(3):253–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0897190012465987.

•• Hasnain M, Rudnick A, Bonnell W, Remington G, Lam R. Use of Placebo in Clinical Trials of Psychotropic Medication (Canadian Psychiatric Association Position Paper). Can J Psychiatry. 2017; In press. The paper discusses important clinical and ethical aspects of the use of plaebo in clinical trials of psychotropic drugs.

Turkel SB, Hanft A. The pharmacologic management of delirium in children and adolescents. Paediatr Drugs. 2014;16(4):267–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40272-014-0078-0.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and animal rights and informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hasnain, M., Tahir, T.A. Use of Antipsychotic Medications in Non-Substance-Related Delirium—the Gap Between Research Findings and Clinical Practices. Curr Treat Options Psych 5, 1–16 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-018-0133-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-018-0133-5