Opinion statement

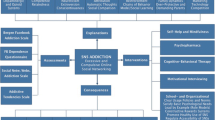

Based on the available evidence, we would offer a Compulsive Buying Disorder (CBD) patient the choice of a 12-session trial of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) targeting CBD, or a seven-week trial of pharmacotherapy with citalopram. We would treat any co-morbid psychiatric disorder with appropriate psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy, and evaluate the need for couples or family therapy, and for inpatient treatment of suicidality, or comorbid conditions. We would also encourage the use of educational self-help materials. Patients preferring pharmacotherapy would be encouraged to take steps to help control CBD behaviors, e.g., identify the needs over-shopping is meeting and design more rational ways to meet them; find other ways to experience pleasure; take a “truly needed” shopping list along and purchase only these items; leave credit cards at home; avoid shopping alone—a friend may curtail compulsive buying; avoid shopping malls or other personally tempting venues; resist the convenience of online shopping and don’t allow websites to store credit card information, as this makes transactions even speedier and thus more dangerous; keep a daily journal of purchases and expenditures and of the irrational thoughts and feelings driving compulsive buying, and use self-help materials to combat them; reward yourself for exerting control. During medication visits, we would inquire regarding any difficulties in implementing these behavioral changes, and help problem-solve these difficulties. If an adequate CBT trial were ineffective, we would recommend a pharmacotherapy trial. If an adequate pharmacotherapy trial (with or without the informal behavioral therapy approaches listed) were ineffective, we would recommend a formal CBT trial. If this trial also failed, we would offer the patient sequential trials of emerging drug therapies (e.g., naltrexone and memantine). We would encourage patients to continue an effective treatment for a year (i.e., with “booster sessions” of CBT or continued drug therapy), to firmly establish the new shopping habits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Compulsive buying disorder (CBD) (also called compulsive shopping, “shopaholism,” or addictive buying) creates immediate pleasure and long-lasting pain. The compulsive buying behavior is usually preceded by a negative mood state and brings temporary relief or pleasure, followed by guilt, shame or remorse. Compulsive buyers frequently buy more than they can afford or buy things they don’t need. The items are rarely used and may be ignored, hidden, returned, or given away. This senseless buying can lead to marital and family friction or impaired work performance. It usually creates financial problems - crushing credit card debt or the waste of money needed for necessities on unnecessary purchases. In some cases, CBD can cause bankruptcy. CBD usually begins in young adulthood. Most sufferers experience buying binges more than once a week.

Medical description began with the psychiatric textbooks of Kraepelin [1] and Bleuler [2], who called the disorder “oniomania” (from the Greek roots for buying madness) and classified it as one of the “impulsive insanities.” They emphasized the presence of an irresistible impulse and the compulsive buyers’ failure to anticipate the “senseless consequences of their act.” Other than a few psychoanalytic case reports, little medical attention was paid to CBD until 1994, when three groups described the disorder [3]. Psychiatrists now consider CBD an impulse control disorder or a behavioral addiction. No officially accepted diagnostic criteria exist; the criteria most widely utilized in clinical research were adapted from the DSM-III-R criteria for obsessive-compulsive disorder and impulse-control and substance use disorders [4]. Compulsive buyers seeking treatment seem excessively prone to episodes of depression, and to anxiety, substance abuse, and eating disorders [5–7].

Although the causes of CBD are unknown, it primarily appears in developed economies, which expose people to abundant consumer goods, easy credit, pervasive advertising, and sophisticated marketing. Materialistic consumer culture values (i.e., the idea that material goods indicate success and bring happiness), may also be a contributing cause. Psychological causes undoubtedly vary across individuals. Many experts believe that CBD is an attempt to escape low self-esteem and negative emotions. Others suggest that compulsive buyers are avoiding important life issues, seeking to nurture themselves, or trying to project an image of wealth and power.

CBD is common. A nationwide, random-sample survey of 2,413 adults in the USA, using a validated questionnaire, found that it seemed present in almost 6 % of the population (6 % of women, 5.5 % of men) [8]. A similar German study found a prevalence of 6.9 %, equal in men and in women [9].

No treatment for CBD has been established as effective, but the literature and our clinical experience indicate that CBD can be overcome. Promising results have been reported from small studies of forms of CBT. In addition, antidepressant drugs that affect the brain’s serotonin system have helped some individuals. Medications affecting other neurochemical systems are under study. A helpful website is: www.stoppingovershopping.com/resources.

Treatment

Before designing a treatment plan, the clinician must distinguish CBD from excessive buying that occurs as a result of a hypomanic or manic episode in bipolar disorder, or as a result of dopaminergic overstimulation from anti-Parkinsonian medications [10]. CBD should also be distinguished from impulsive buying without adverse consequences, from “revenge spending” (to deplete another person’s funds) [11], and from hoarding behaviors associated with isolated hoarding, OCD hoarding, or hoarding symptomatic of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. Impulsive buying is triggered by a desire for a particular item and usually occurs infrequently and without adverse consequences. Buying associated with hoarding is usually motivated not by urges to engage in buying, but by a thought that the item(s) “might be needed sometime,” or by the need to buy things only when they are on sale.

Once the diagnosis is made, establishing a baseline for the severity of the disorder is useful. In clinical studies, the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale- Shopping Version (YBOCS-SV), which has excellent sensitivity to clinical change, is frequently used [12]. The clinician-rated YBOCS-SV rates obsessions and, separately, compulsions related to compulsive shopping with regard to five dimensions: time spent, degree of interference with functioning, distress caused, resistance, and success in resisting. Total scores for the 10 items range from 0 to 40. In a small validation study, untreated compulsive shoppers had a mean score of 21 (range 18–25) compared with normal shoppers’ mean score of 4 (range 1–7) [12].

A second step is treatment planning is to take into account and treat co-morbid psychiatric disorders, since these may be contributing to the CBD severity (e.g., major depression), or may interfere with the patient’s ability to cooperate with or adhere to treatment. Rates of comorbidity in CBD individuals identified in random sample population surveys have yet to be determined. In clinical samples, current and lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders are high. Studies of CBD participants in treatment or descriptive studies have, however, evaluated only samples of modest size (i.e., 50 cases or less). Although lifetime comorbidity rates are high, the exact percentages reported vary widely: mood disorders (21 %–100 %), anxiety disorders (41 %–80 %), substance use disorders (21 %–46 %), eating disorders (8 %–35 %), and other impulse control disorders (21 %–40 %) [13•, Class II]. In two studies with comparison control groups, major depression and any mood disorder were more common in CBD subjects in one [6]; in the other, all the categories just listed, except major depression, were more common in the CBD subjects [5].

There is no established treatment for CBD. The studies published to date have been too heterogeneous in design, small in sample size, or inconsistent in findings to allow strong, generalizable treatment recommendations [13•, Class II].

Pharmacologic treatment

The aims of drug therapy are: to bring about remission of the compulsive buying behaviors; to prevent relapse; and to bring into remission (or substantially ameliorate) any co-morbid psychiatric conditions, including mood disorders, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, substance abuse disorders, or other impulse control disorders. In many instances, this goal will require not only pharmacotherapy, but also psychotherapy. In addition, couples or family therapy (or education) may be indicated, and occasionally inpatient treatment (e.g., for the suicidal patient or the patient with other severe symptoms).

Treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

Early case series using serotonergic and other antidepressants to treat CBD reported encouraging results, but were limited by the presence of comorbid mood or anxiety disorders; by the concomitant use of psychotherapy or other medications; and by the inconsistent length of treatment [4, 14]. The preliminary positive findings inspired open-label trials with fluvoxamine [15] and citalopram [16] in subjects with CBD, but free of severe major depression comorbidity.

Fluvoxamine

In a nine-week open-label fluvoxamine trial, 9 of 10 CBD subjects (90 %) responded to the drug (mean dose: 205 mg/day) [15].

The results of subsequent double-blind, randomized studies, however, have been mixed. In two randomized controlled trials, fluvoxamine failed to separate from placebo. In the nine-week trial, 12 non-depressed subjects received fluvoxamine (<300 mg/day) and 11 received placebo [17]. At study end, 50 % of subjects randomized to fluvoxamine had responded, compared with 64 % of those receiving placebo. Similarly, in the 12-week study randomizing 20 subjects to fluvoxamine (mean dose: 215 mg/day) and 17 to placebo, the intent-to-treat analysis revealed no statistically significant difference in response rates [18].

- Standard dosage:

-

50–300 mg/day (patients aged 8–17 years, 50–200 mg/day). After starting with 50 mg/day, the dose may be increased by 50 mg/day every 4–7 days [19].

- Contraindications:

-

Co-administration of terfenadine, thioridazine, tizanidine pimozide, alosetron, astemizole and ramelteon is contraindicated. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (including linezolid or IV methylene blue), should not be administered within 14 days of fluvoxamine discontinuation, and vice-versa [19].

- Main drug interactions:

-

Fluvoxamine inhibits CYP1A2, CYP2C19 and CYP3A4. Thus, interactions with drugs partially metabolized by these enzymes may occur. For CYP1A2 these drugs include: tizanidine, tertiary-amine tricyclic antidepressants (imipramine, amitriptyline, and clomipramine), clozapine, tacrine, theophylline, propranolol, and caffeine. CYP2C19 metabolizes warfarin. CYP3A4 is involved in the metabolism of alprazolam, midazolam, triazolam and diazepam, carbamazepine, mexiletine, pimozide, methadone, and thioridazine [19].

- Main side effects:

-

The most common side effects are diarrhea, loss of appetite, nausea, asthenia, insomnia, somnolence, and sexual side effects [19].

- Special points:

-

Fluvoxamine can precipitate mania in bipolar patients. Like all SSRIs, fluvoxamine carries an FDA-mandated warning that it may increase suicidal thinking and behavior in children, adolescents and young adults (ages18 to 24). Because of the risk of bleeding, patients should be cautioned about concomitant use of fluvoxamine and NSAIDs, aspirin, and other drugs affecting coagulation. Hyponatremia may occur with all SSRIs, including fluvoxamine; risk is increased in the elderly, volume-depleted patients, and by diuretics. Serotonin syndrome has been reported when other serotonergic drugs were co-administered, (e.g., fentanyl, tramadol and tryptophan). When stopping fluvoxamine, gradual dose reduction is preferable to sudden discontinuation, in order to avoid withdrawal symptoms [19].

- Cost/cost effectiveness:

-

Relatively inexpensive because it is available as a generic. No cost effectiveness data are available.

Citalopram

In a seven-week open-label citalopram trial, 17 of 24 CBD subjects (71 %) responded (mean dose: 35.4 mg/day). During a six-month follow-up period, those continuing citalopram were less likely to relapse than those discontinuing the medication [16]. However, a one-year naturalistic follow-up study found that, while responders at the end of the seven-week trial were significantly more likely to be in remission at one year than non-responders, no clear association was seen between continuing citalopram and remission [20]. The small sample size constrains interpretation of these findings.

A discontinuation trial of citalopram in subjects with CBD (N = 24) suggested effectiveness of the drug [21]. In this trial, all subjects received seven weeks of open-label citalopram (<60 mg/day). At the end of this period, 15 subjects (63 %) were responders (Clinical Global Impression-Improvement score of much, or very much, improved; and Y-BOCS-SV score decrease ≥ 50 %). The responders were entered into the double-blind study phase, where they were randomized to nine weeks of either continued citalopram or placebo. Five of eight subjects (62.5 %) assigned to placebo relapsed, compared with none of the citalopram-assigned subjects.

- Standard dosage:

-

20-40 mg/day (20 mg/day for age > 60 years). Start with 20 mg/day; after no less than one week, the dose may be increased to 40 mg/day [19].

- Contraindications:

-

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, including linezolid or IV methylene blue, should not be administered within 14 days of citalopram discontinuation, and vice-versa. Concomitant use with clorgyline, toloxatone, nialamide, fluconazole, posaconazole, pimozide, ziprasidone, sparfloxacine, piperaquine, levomethadyl acetate hydrochloride, mesoridazine, thioridazine, dronedarone, cisapride, amifampridine, and metaclopramide is contraindicated. Concurrent use of citalopram with other drugs that prolong the QT interval may increase the risk of serious arrhythmias, including torsade de pointes [19].

- Main drug interactions:

-

Concomitant use of citalopram and precursors of serotonin, such as tryptophan, and serotonergic drugs is not recommended owing to the increased risk of serotonin syndrome [19].

- Main side effects:

-

These are reported as increased sweating, constipation, dry mouth, nausea, dizziness, insomnia, somnolence, tremor, and sexual side effects [19].

- Special points:

-

The FDA warned (August 2011, March 2012) against doses higher than those noted above because of concerns about QTc prolongation, but this is controversial [22, 23]. Risk factors for QTc prolongation are: heart failure, prior MI, diabetes, low serum K + or Mg++, congenital long QT syndrome, and concomitant use of CYP2C19 inhibitors (e.g., cimetidine). Citalopram can precipitate mania in bipolar patients. Like all SSRIs, citalopam carries an FDA-mandated warning that it may increase suicidal thinking and behavior in children, adolescents and young adults (ages 18 to 24). Because of the risk of bleeding, patients should be cautioned about concomitant use of citalopram and NSAIDs, aspirin, and other drugs affecting coagulation. Hyponatremia may occur with all SSRIs, including citalopram; risk is increased in the elderly, volume-depleted patients, and by diuretics. Dose reduction may be needed for patients with hepatic impairment or severe renal impairment. Serotonin syndrome has been reported when other serotonergic drugs were co-administered (e.g., fentanyl, tramadol and tryptophan). When stopping citalopram, gradual dose reduction is preferable to sudden discontinuation, in order to avoid withdrawal symptoms [19].

- Cost/cost effectiveness:

-

Relatively inexpensive because it is available as generic. No cost effectiveness data are available.

Escitalopram

A discontinuation study of escitalopram (the S-enantiomer of citalopram), for the treatment of CBD, utilized a design identical to that of the citalopram discontinuation study above. The newer study failed to find statistically significant separation of escitalopram from placebo [24]. In the seven-week open-label phase, 19 of 26 subjects (73 %) responded to escitalopram (<20 mg/day), but at the end of the nine-week double–blind phase, 5 of 8 (62.5 %) escitalopram subjects had relapsed, compared with 6 of 9 (66.7 %) placebo subjects.

- Standard dosage:

-

10-20 mg/day (10 mg/day for age > 60 years). Start with 10 mg/day; after no less than one week, the dose may be increased to 20 mg/day [19].

- Contraindications:

-

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, including linezolid or IV methylene blue, should not be administered within 14 days of escitalopam discontinuation, and vice-versa [19].

- Main side effects:

-

These are reported as diarrhea, nausea, insomnia, somnolence, increased sweating, and sexual side effects [19].

- Special points:

-

Escitalopram can precipitate mania in bipolar patients. Like all SSRIs, escitalopam carries an FDA-mandated warning that it may increase suicidal thinking and behavior in children, adolescents, and young adults (ages 18 to 24).

Because of risk of bleeding, patients should be cautioned about concomitant use of escitalopram and NSAIDs, aspirin, and other drugs affecting coagulation. Hyponatremia may occur with all SSRIs, including escitalopram; risk is increased in the elderly, volume-depleted patients, and by diuretics. Dose reduction may be needed in patients with hepatic impairment or severe renal impairment. Serotonin syndrome has been reported when other serotonergic drugs were co-administered (e.g., fentanyl, tramadol, and tryptophan). When stopping escitalopram, gradual dose reduction is preferable to sudden discontinuation, in order to avoid withdrawal symptoms [19].

- Cost/cost effectiveness:

-

Relatively inexpensive because it is available as a generic. No cost effectiveness data are available.

Other treatments

Psychotherapy

-

Psychoanalytic formulations have been proposed to explain compulsive buying, and several positive psychoanalytic case reports exist [13•, Class II]. In aggregate, these reports do not provide adequate evidence to allow recommending psychoanalysis as the sole treatment modality for a patient with CBD.

-

Some authors suggest that the faulty cognitions associated with compulsive buying (e.g., fear of missing out on a “deal;” buyer’s overestimation of his or her wealth; assumed enhancement of status and happiness through purchases) may respond well to CBT [25], and a growing body of data supports this form of treatment [13• Class II, 25].

-

Individual CBT treatment of CBD has not been tested in controlled trials, but three studies have tested manualized CBT delivered in a group therapy format [26, 27, 28• Class III]. The intervention included teaching CBT subjects methods for interrupting and controlling problematic buying; establishing healthier buying patterns, in part by keeping a daily record of purchases, along with their antecedents and appropriateness or lack thereof; confronting maladaptive thoughts and emotions associated with buying, including materialistic values; and encouraging better coping strategies, including problem-solving and stress management. The first study compared group CBT to a wait-list control [26]. Twenty-eight subjects were assigned to receive group CBT and 11 to the wait-list. Group CBT consisted of twelve 1.5 hour sessions over 10 weeks. Among study completers, 12 of 21 individuals (57 %) who received CBT reported total remission, compared with none in the wait-list group. A similar 12-week, German study replicated this finding in a larger group (n = 60) [27]. At six-month follow-up, 10 of 17 (59 %) subjects who received CBT in the first study [26] reported remission (no compulsive buying), during the month preceding the follow-up assessment. The second study reported that mean scores on three outcome measures remained improved at the six-month follow-up, but neither remission nor response rates are provided [27].

-

A more recent pilot study (N = 56) randomized subjects to one of three groups: manualized group CBT treatment (12 sessions); a less intensive telephone-guided self-help intervention (a self-help book, homework assignments, and five 20-minute telephone sessions with a CBT therapist who clarified and discussed any difficulties and provided support); or a wait-list control. Participants in both active treatment groups showed improvement compared with the wait-list group, but face-to-face group CBT produced greater improvement than telephone-guided self-help as measured by both the Compulsive Buying Scale and the YBOCS-SV scale. The improvements in Compulsive Buying Scale and Y-BOCS-SV scale scores for both treatment groups were largely maintained at six-month follow-up, but remission rates are not provided [28, Class III].

-

Given the interpersonal and financial stresses associated with CBD, couples or family counseling may be indicated, but no studies of these interventions have been published. Referral to financial advisors may also benefit patients.

Cost/cost effectiveness

No data regarding the cost or cost-effectiveness of these psychotherapeutic interventions are available.

Public health interventions

Given that social factors may be contributory causes of CBD, and given physicians’ role in advocating public health measures to diminish illness impact and prevalence, physicians may wish to take action regarding the putative contribution of these social factors.

Public policy initiatives that may benefit patients and others who suffer the effects of runaway consumerism without meeting CBD diagnostic criteria have been advocated. Benson and co-authors [29•, Class III] have suggested educational, legislative, and home-based strategies that challenge the assumptions made by many victims of consumerism: that more is better; that the next purchase will bring lasting happiness; and that material goods make the man (or woman).

On the educational front, these authors suggest that schools could be encouraged to provide financial and media literacy courses to help students become intelligent consumers who understand money management and how advertising manipulates desire. College administrators could curtail on-campus marketing by credit card companies.

Legislative action could target the predatory or deceptive practices sometimes employed by the financial industry to prey on individuals who may not comprehend the “fine print” and the consequences of their choices, or who may be too poor to pay back even modest debt. Media outlets could be given incentives to run public service messages about how to diminish the under-recognized costs of consumerism. Such interventions would be politically sensitive and would require consideration of the right to free speech.

Finally, these authors suggest that parents could model responsible buying behavior and inculcate non-materialistic values, avoiding the temptation to entice their children with “things” and material rewards. To help parents, compulsive buyers, and consumers in general, they recommend resources, including books, self-help manuals, non-profit organizations, and educational opportunities that can be accessed at www.stoppingovershopping.com/resources,

Emerging therapies

Hypothesized relationships of CBD with obsessive-compulsive disorder and impulse control disorders have led to attempts to treat CBD with drugs that have shown promise in treating those conditions.

Naltrexone

The mu opioid receptor antagonist, naltrexone, has been reported to be effective and well tolerated in seven cases of CBD [30, 31]. The effective dose range was 100–200 mg/day [30].

- Contraindications:

-

Naltrexone contraindications are hepatitis or liver failure, and concomitant use of opioid analgesics [19].

- Special points:

-

Naltrexone should be discontinued if signs or symptoms of acute hepatitis occur. However, a dose of 150 mg/day was tolerated for a mean of 328 days without liver irritation in 41 patients who were instructed to avoid concomitant use of acetaminophen, aspirin, or non-aspirin, non-steroidal, anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [32].

- Cost/cost effectiveness:

-

Relatively inexpensive because it is available as a generic. No data regarding cost effectiveness are available.

Memantine

A 10-week open-label trial of the NMDA receptor antagonist memantine 10–30 mg/day, enrolled nine subjects with CBD. Eight completed the study. Mean YBOCS-SV scores decreased from 22.0 to 11.0 at endpoint, along with time and money spent shopping per week. The mean effective memantine dose was 23.4 mg/day. The most common side effect was dizziness (33 %), but all side effects were mild to moderate in intensity, and all resolved without sequelae [33•, Class IV].

- Standard dosage:

-

Standard dosage in Alzheimer’s disease is 5 mg/day increased by 5 mg/day weekly to 20 mg/day [19]. In the study cited above [33•, Class IV], a higher dose was utilized.

- Contraindications:

-

Memantine is contraindicated in patients with known hypersensitivity to the drug or components used in its formulation [19].

- Main side effects:

-

These are reported as diarrhea, confusion, dizziness, and headache in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

- Special points:

-

Memantine is eliminated in part by the kidneys, and clearance is markedly reduced by drugs that alkalinize the urine (e.g., carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, sodium bicarbonate). Memantine should be used with caution in patients with severe hepatic impairment or cardiovascular diseases [19].

- Cost/cost effectiveness:

-

Relatively inexpensive because it is available as a generic. No data regarding cost effectiveness are available.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Kraepelin E. Psychiatrie (8th edition), Leipzig: Verlag Von Johann Ambrosius Barth; 1915. pp. 408-9.

Bleuler E. Textbook of Psychiatry. New York: McMillan; 1924.

Black DW. A review of compulsive buying disorder. World Psychiatr. 2007;6:14–8.

McElroy S, Keck PE, Pope Jr HG, et al. Compulsive buying- a report of 20 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55:242–8.

Christenson GA, Faber RJ, De Zwaan M. Descriptive characteristics and psychiatric comorbidity of compulsive buying. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55:5–11.

Black DW, Repertinger S, Gaffney GR, Gabel J. Family history and psychiatric comorbidity in persons with compulsive buying: preliminary findings. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:960–3.

Mueller A, Mitchell JE, Mertens C, et al. Comparison of treatment seeking compulsive buyers in Germany and the United States. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:1629–38.

Koran LM, Faber RJ, Aboujaoude E, et al. Estimated prevalence of compulsive buying in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1806–12.

Mueller A, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, et al. Estimated prevalence of compulsive buying in Germany and its association with socio-demographic characteristics and depressive symptoms. Psychiatr Res. 2010;180:137–42.

Weintraub D, Siderowf AD, Potenza MN, et al. Association of dopamine agonist use with impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:969–73.

Krueger D. On compulsive shopping and spending: a psychodynamic inquiry. Am J Psychother. 1988;42:574–84.

Monahan P, Black DW, Gabel J. Reliability and validity of a scale to measure change in persons with compulsive buying. Psychiatry Res. 1996;64:59–67.

Black DW. Compulsive buying: clinical aspects, Chapter 1. In: Aboujaoude E, Koran LM, editors. Impulse Control Disorders. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2010. p. 5–22. [Class II] The chapter is a thorough review of the history, epidemiology, course, and treatment of CBD.

McElroy S, Satlin A, Pope Jr HG, et al. Treatment of compulsive shopping with antidepressants: a report of three cases. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1991;3:199–204.

Black DW, Monahan P, Gabel J. Fluvoxamine in the treatment of compulsive buying. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:159–63.

Koran LM, Bullock KD, Hartson HJ, et al. Citalopram treatment of compulsive shopping: An open-label study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:704–8.

Black DW, Gabel J, Hansen J, et al. A double-blind comparison of fluvoxamine versus placebo in the treatment of compulsive buying disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2000;12:205–11.

Ninan PT, McElroy SL, Kane CP, et al. Placebo-controlled study of fluvoxamine in the treatment of patients with compulsive buying. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20:362–6.

Micromedex 2.0 (Micromedexsolutions.com, accessed online February 25, 2014).

Aboujaoude E, Gamel N, Koran LM. A 1-year naturalistic follow-up of patients with compulsive shopping disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:946–50.

Koran LM, Chuong HW, Bullock KD, et al. Citalopram for compulsive shopping disorder: an open-label study followed by a double-blind discontinuation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:793–8.

Zivin K, Pfeiffer PN, Bohnert ASB, et al. Evaluation of the FDA warning against prescribing citalopram at doses exceeding 40 Mg. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:642–50.

Bird ST, Crentsil V, Temple R, et al. Cardiac safety concerns remain for citalopram at dosages above 40 mg/day. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:17–9.

Koran LM, Aboujaoude EN, Solvason B, et al. Escitalopram for compulsive buying disorder: a double-blind discontinuation study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:225–7.

Lejoyeux M, Weinstein A. Compulsive buying. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36:248–53.

Mitchell JE, Burgard M, Faber R, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for compulsive buying disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(12):1859–65.

Mueller A, Mueller U, Silbermann A, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of group cognitive-behavioral therapy for compulsive buying disorder: Posttreatment and 6-month follow-up results. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(7):1131–8.

Müller A, Arikian A, Zwaan M, et al. Cognitive-behavioural group therapy versus guided self-help for compulsive buying disorder: A preliminary study. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2013;20(1):28–35. [Class III] The study is a controlled trial of intensive group CBT compared to guided self-help and a waitlist group. Face to face CBT was superior to the guided self-help group and waitlist condition.

Benson AL, Dittmar H, Wolfson R. Compulsive buying: cultural contributors and consequences, Chapter 2. In: Aboujaoude E, Koran LM, editors. Impulse Control Disorders. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2010. p. 23–33. [Class III] The chapter is a thorough review of the cultural and social factors at play in CBD and how public policy interventions can help mitigate the pressures felt by the average consumer and excessive buyer.

Kim SW. Opioid antagonists in the treatment of impulse-control disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:159–64.

Grant JE. Three cases of compulsive buying treated with naltrexone. Int J Psychiatr Clin Pract. 2003;7:223–5.

Kim SW, Grant JE, Yoon G, et al. Safety of high-dose naltrexone treatment: hepatic transaminase profiles among outpatients. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2006;29:77–9.

Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Mooney M, et al. Open-label pilot study of memantine in the treatment of compulsive buying. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2012;24(2):119–26. [Class IV] The open label study is the first trial in CBD of memantine, a glutamatergic drug that has shown promise in the treatment of OCD.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Lorrin M. Koran has received money outside of the submitted work for his consultancy work for F. Hoffman LaRoche, Inc. and for service on speakers bureaus on behalf of Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Both Lorrin M. Korrin and Elias Aboujaoude have received royalties from Cambridge University Press from their book, Impulse Control Disorders.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does contains studies with citalopram and escitalopram performed by the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Koran, L.M., Aboujaoude, E. Treating Compulsive Buying Disorder. Curr Treat Options Psych 1, 315–324 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-014-0024-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-014-0024-3