Abstract

We identified, summarized, and appraised the certainty of evidence for 12 studies investigating the use of music therapy for individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The studies were summarized in terms of (a) participant characteristics, (b) dependent variables, (c) procedures, (d) results, and (e) certainty of evidence. A total of 147 participants aged 3 to 38 years were included in the 12 studies. Dependent variables included: (a) decreasing undesirable behavior, (b) promoting social interaction, (c) improving independent functioning, (d) enhancing understanding of emotions, and (e) increasing communication. Music therapy included the use of specific songs with lyrics related to target skills as well as musical improvisation. Outcomes were positive for 58 % of the studies and mixed for 42 % of the studies. Certainty of evidence was rated as conclusive for 58 % of the studies. The existing literature suggests that music therapy is a promising practice for individuals with ASD, but additional research is warranted to further establish its generality and the mechanisms responsible for behavior change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by persistent deficits in social communication, social interaction, and restricted and repetitive behaviors, interests, or activities (American Psychiatric Association 2013). The symptoms of ASD are identifiable in early development and cause a significant impairment in social, occupational, and/or daily functioning (Horovitz et al. 2011; Lang et al. 2010). The symptoms of ASD can vary in terms of severity. For example, it has been estimated that between 25 to 61 % of individuals with ASD do not develop functional speech. While others might develop speech, it is often used in restrictive or stereotyped ways (Prizant 1996; Schlosser and Wendt 2008). Additionally, severe intellectual disability (i.e., IQ <50) appears to be evident in about 25 to 50 % of ASD cases, but average and even above average IQ scores have been identified in some people with ASD (Edelson 2006; Geschwind 2009; Mirenda 2008). Given this range in severity, it is perhaps not surprising that a range of treatment options have been investigated (Green et al. 2006).

Music therapy is one treatment that has been used for children with ASD (Green et al. 2006; Reschke-Hernández 2011). Music therapy has been defined as “a systematic process of intervention wherein the therapist helps the client to promote health using musical experiences and relationships that develop through them as dynamic forces of change” (Bruscia 1998, p. 20). A more recent definition has been provided by the World Federation of Music Therapy (WFMT):

Music therapy is the professional use of music and its elements as an intervention in medical, educational, and everyday environments with individuals, groups, families, or communities who seek to optimize their quality of life and improve their physical, social, communicative, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual health and wellbeing. Research, practice, education, and clinical training in music therapy are based on professional standards according to cultural, social, and political contexts (WFMT 2011).

As the number of children diagnosed with ASD has increased, there also appears to have been an increased demand for music therapy services for this population (Reschke-Hernández 2011). Wigram et al. (2002) discussed music therapy in special education settings, where music therapists work with individuals with learning disabilities, challenging behavior, social skill deficits, and comorbid psychological conditions. They asserted that music therapists use music as a tool by which to meet the needs of the clients.

The American Music Therapy Association (AMTA) emphasizes that music therapy should only be implemented by individuals trained in music therapy. Within the USA, this involves a bachelor’s degree or higher in music therapy, including 1200 h of clinical training and board certification (AMTA 2014). Requirements elsewhere (including Great Britain, Germany, Scandinavia, Canada, South America, Australia, and New Zealand) involve clinical training programs at the undergraduate or graduate level. Additionally, many countries require music therapists to be registered with the appropriate authorities in order to practice (Grocke and Wheeler 2001).

Music therapy can involve one or more of the following techniques: (a) free improvisation (i.e., without any stated boundaries for the music), (b) structured improvisation (i.e., some established parameters for the music), (c) performing or recreating pre-composed music, songs, and associated activities, (d) composing songs and instrumental music, and/or (e) engaging in listening experiences (Wheeler et al. 2005). Wheeler et al. (2005) argued for the usefulness of improvisation and pre-composed music and activities for working with children with special needs. They noted that songwriting might not be appropriate for younger children who lack the required literacy skills, but that this might be an enjoyable experience and a potential learning tool for adolescents. In contrast, isolated receptive listening experiences appear to be used less commonly (Wheeler et al. 2005).

Music therapy goals also vary widely and are determined by the needs of the client. Kaplan and Steele (2005) analyzed music therapy goals and outcomes for 40 music therapy clients with ASD over a two-year period. The analysis involved synthesis of data provided by an agency-wide computerized music therapy outcomes-based measurement program that tracked data for each individual who received music therapy services in a community-based music therapy program over the two-year time period. Participants ranged from 2 to 49 years of age (M = 13.9 years) and the sample included more males (70 %) than females (30 %). Participants received either individual or group music therapy sessions. Results suggested that music therapy goals focused primarily on improving communication and language as well as promoting behavioral and social skills.

In addition to examining goals, Gold et al. (2006) reviewed the efficacy of music therapy for individuals with ASD. They reviewed research up to July 2004 and included only studies involving a randomized control trial or controlled clinical trial design. Three studies met their inclusion criteria. The participants in these three studies were between 2 and 9 years of age, had been diagnosed with ASD, and received individual music therapy sessions. A summary of the outcomes suggested that music therapy had positive effects on nonverbal communication, gestural communication, and verbal communication. However, these three studies were limited in three ways. First, music therapy was provided for 1 week only in each of the three studies. Second, sample sizes were fairly small (4 to 10 participants). Third, only one study included active music making, which appears to be the more typical clinical practice (Wigram and Gold 2006).

In contrast to Gold et al.’s (2006) review, Accordino et al. (2007) undertook a narrative review of the literature. They identified 20 studies, published between 1973 and 2000. Eleven were case studies. The participants ranged from 3 to 41 years of age and, at least one participant in each study had an ASD diagnosis. They classified therapy approaches in the following categories: (a) improvisational music therapy, (b) receptive music therapy, (c) activity music therapy, (d) melodic intonation therapy, (e) rhythmic entrainment, (f) musical synchronization, (g) behavioral therapy, (h) musical interaction therapy, and (i) auditory integration training (AIT). The most common approaches were AIT (seven studies), improvised music therapy (seven studies), and activity music therapy (five studies). Therapy outcomes were categorized as communicative, social, or behavioral. Seventeen studies focused on communication, 15 focused on social skills, and 12 focused on challenging behavior. Many of the studies addressed more than one of these outcomes. Based on their review of these studies, Accordino et al. (2007) concluded that there was limited empirical support for music therapy.

However, it is important to note that seven of the 20 studies in Accordino et al.’s (2007) review used AIT. The inclusion of AIT could have negatively skewed the overall analysis of the effects of music therapy because AIT has been repeatedly demonstrated to be ineffective (Mudford and Cullen 2005). Unlike music therapy, AIT is a form of sound or listening therapy predicated on an entirely different hypothesized mechanism of action (physiologically-oriented) to music therapy.

The inclusion of AIT in the narrative review by Accordino et al. (2007) and the omission of single-case research studies and the elapsed time since Gold et al.’s (2006) review would therefore seem to justify a further examination of the literature on music therapy for the treatment of individuals with ASD. The aim of the present review was to provide an updated review of both group and single-case studies that have evaluated music therapy for individuals with ASD. A review of this type was considered necessary to determine whether music therapy could be considered an evidence-based practice. Such information would be useful in the selection of treatment options for children with ASD. Our review was also intended to identify directions for future research.

Method

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies included in this systematic review had to involve experimental (randomized control trials, multiple-baseline designs) or quasi-experimental (e.g., A-B design) designs. The studies also had to have investigated the effects of music therapy on the behavior of at least one individual with ASD. Music therapy interventions were defined by the following criteria: (a) the use of music as a tool to address nonmusical goals, and (b) at least one of the researchers was a qualified music therapist or the study stated that music therapy sessions were conducted by a music therapist. Descriptive studies and studies on assessment of skills were excluded, as were other reviews and theoretical papers.

Search Procedures

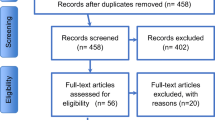

Four electronic databases were searched: (a) PsycINFO, (b) MEDLINE, (c) Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literatures (CINAHL), and (d) Education Resources Information Center (ERIC). Publication years were from 2004 until September 2013, as previous studies have reviewed the literature on music therapy and ASD up to 2004 (see Accordino et al. 2007; Gold et al. 2006). The search was also limited to English-language journal articles. In all database searches, the search terms music therapy and autism (with relevant BOOLEAN operators) were used.

A review of the abstracts of identified studies was utilized to determine inclusion in the review. The reference lists of the included studies were examined to identify any further possible studies for inclusion. Hand searches were completed for all of the journals in which the identified studies were published, and additional hand searches were conducted in the New Zealand Journal of Music Therapy, Australian Journal of Music Therapy, Canadian Journal of Music Therapy, and musictherapyworld.net (which contains an online journal and other archives). An author search for additional publications from each of the authors identified in the included studies was conducted in the four electronic databases. As a result of these search procedures, 19 studies were identified for possible inclusion in this systematic review. Each of these 19 studies was then assessed to determine whether it met the inclusion criteria (see “Inter-rater Agreement”).

Data Extraction

A summary of each study was generated in terms of (a) participants, (b) target skills for therapy (dependent variables), (c) music therapy intervention procedures, (d) intervention outcomes, and (e) certainty of evidence.

Intervention outcomes were rated as positive, negative, or mixed, in accordance with the definitions provided by Lang et al. (2012). Positive outcomes in single-case research were determined by visual analysis of data suggesting improvement in all dependent variables for all participants. Positive outcomes from studies involving a group design were determined by a statistically significant improvement in the music therapy treatment group compared with the control group. Negative outcomes in single-case research were determined by visual analysis of data suggesting no improvement for any of the participants on any of the dependent variables, while negative outcomes in group research were determined by the absence of statistically significant improvement in the treatment group. Mixed outcomes in single-case research showed some improvements for some dependent variables or for some participants, while mixed outcomes from studies involving a group design showed statistically significant improvements for some of the dependent variables in the experimental group.

The certainty of evidence of each study was rated as insufficient, preponderant, or conclusive based on the definitions provided by Davis et al. (2013). Studies using quasi-experimental designs were rated as capable of providing only insufficient certainty of evidence. For studies to be rated at the preponderant level, they were required to have (a) an experimental design, (b) inter-observer agreement (IOA) data collected in at least 20 % of the sessions, and with the resulting agreement of 80 % or higher, (c) operationally-defined dependent variables, and (d) sufficient methodological detail to replicate the study. However, these studies were limited in some way with confounds that affected their ability to control for alternative explanations for intervention effects. For example, confounds related to attrition, carry-over, or blinding may have been present. Studies rated as having conclusive evidence possessed all the features described at the preponderant level and attempted to control for alternative explanations for intervention effects and may have also included measures for treatment fidelity.

Inter-rater Agreement

The first author examined the initial set of 19 studies to determine whether each met the inclusion criteria. The ninth author independently assessed these 19 studies against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Agreement on inclusion and exclusion of studies was initially obtained for 16 of the 19 studies (84 %). After discussion to clarify the criteria, consensus was reached to exclude 7 studies and include 12 studies in this systematic review.

Guided by the procedures outlined in Sigafoos et al. (2009), the first author produced summaries of each of the 12 included studies, which were assessed by the eighth author for accuracy and generate a measure of inter-rater agreement for data extraction and analysis. Each summary was read and checked against the original study, and a checklist of five questions was completed to indicate the accuracy of the summary with regard to participants, target skills, interventions, outcomes, and certainty of evidence. There were 60 items for which there could be inter-rater agreement or disagreement, as there were 12 studies with 5 questions each. There was agreement on 59 of the 60 items (98 %).

Results

From a pool of 19 studies, 7 were excluded, leaving 12 studies for summary and analysis. The appendix provides the details of excluded studies, while included studies are indicated in the reference list with an asterisk. Table 1 provides summaries of the participants, target skills, procedures, main findings, and certainty of evidence for each of the 12 included studies.

Participants

Within these 12 studies, a total of 147 participants received music therapy. Two studies did not report the participants’ genders, but the other studies had a collective total of 77 males and 8 females. Participant ages ranged from 3 to 38 years (M = 6.97 years). In a majority of studies, participants were between 3 and 5 years of age.

Sample size of individuals in studies ranged from 1 to 50 participants (M = 12.25). Two studies included only 1 participant [Studies 4 and 9], three studies had 2 to 4 participants [Studies 1, 2, and 5], and four studies had 8 to 12 participants [Studies 3, 6, 7, and 8]. The remaining three studies had sample sizes of 22, 24, and 50 participants, respectively [Studies 10, 11, and 12]. All of the participants had been diagnosed with a type of ASD. One study specified that, of the 24 participants included, 10 had diagnoses of autistic disorder, while 12 had diagnoses of pervasive developmental disorder, not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), and two had diagnoses of Asperger’s disorder [Study 11]. Four studies used the Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS; Schopler et al. 1988, 1998) to identify the severity of ASD for each participant [Studies 2, 5, 9 and 10]. From the 57 participants in these four studies, 25 were categorized as having mild symptoms of autism, five were categorized as having mild/moderate symptoms, 26 were categorized as having moderate/severe symptoms, and one was categorized as having severe symptoms.

Settings

Intervention settings were described for 7 of the 12 studies [Studies 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 9, and 11]. Of these, one study was conducted at a private practice clinic [Study 6], one was conducted in a hospital [Study 11], one was conducted in participants’ homes [Study 1], three were conducted in a preschool [Studies 2, 4, and 5], and one was split between the participant’s home and a preschool [Study 9]. The research took place in a range of countries, including the USA, Canada, South Korea, Italy, Japan, and Brazil.

Dependent Variables

Target skills for intervention were coded into five categories: (a) decreasing undesirable behavior, (b) promoting social interaction and social communication, (c) improving independent functioning, (d) enhancing understanding of emotions, and (e) increasing verbal communication. Two studies, involving 11 participants [Studies 1 and 3] targeted decreasing undesirable behaviors, such as aberrant vocalizations, rewinding/fast forwarding video tapes, rummaging in the kitchen, or psychomotor agitation (although the authors did not operationally define psychomotor agitation). Social interaction and social communication were the broad foci for five studies, involving 49 participants [Studies 2, 6, 8, 9, and 11]. Specific targets in this category included increasing peer interaction and participation; facilitating joint attention behaviors and nonverbal communication skills; and increasing emotional, motivational, and interpersonal responsiveness in joint engagement.

Independent functioning featured in two studies, involving three participants [Studies 4 and 5]. The target skills involved increasing independent completion of multi-step tasks, such as hand washing, toileting, cleaning up, and performing a morning greeting routine at preschool. One study [Study 7], with 12 participants, focused on developing understanding of four emotions (i.e., happiness, sadness, anger, and fear) by measuring participants’ abilities to recognize facial expression in pictures and facially express corresponding emotions themselves. Finally, three studies, including 96 participants, focused on increasing verbal communication [Studies 10, 11, and 12]. Study 11 was the only study that was identified in two categories, namely verbal communication and social interaction/social communication.

Intervention Procedures

Many of the studies implemented music therapy interventions featuring the use of specific songs with lyrics related to target skills [Studies 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, and 12]. Ninety-five of the 147 participants (65 %) received this type of intervention approach. Two studies used pre-composed songs that fit the purposes of the intervention, including a song about cleaning up, and children’s songs about emotions [Studies 4 and 7]. Three studies used adapted lyrics set to familiar melodies [Studies 1, 4, and 9], and six studies used originally composed lyrics and music [Studies 2, 4, 5, 7, 10, and 12]. In Study 1, a prescriptive song protocol was used to compose song lyrics based on social stories (Gray and Garand 1993). In Study 10, a video recording of the songs was made, which the participants watched in the intervention.

Several studies focused on music improvisation as the main music therapy approach [Studies 6, 7, 8, and 11]. Fifty-six of the 147 participants (38 %) received this type of intervention. Studies 6 and 8 divided improvised music therapy sessions into two halves. The first half involved following the child’s lead in musical play, which was then supported by the therapist. The second half was therapist-directed, that is the therapist introduced modeling and turn-taking activities. In addition to pre-composed songs, Study 7 used recordings of piano improvisations to represent four emotions: happiness, sadness, anger, and fear. The recordings were then played as background music during verbal instruction for each emotion. Study 11 used relational music therapy, which was described as an approach where sessions were mainly client-led and improvised activities were used. Study 3 involved active music therapy sessions including drumming, singing, and piano playing. However, it is unclear whether these were structured or improvisational activities.

Study Designs

Studies were classified as experimental or quasi-experimental. Quasi-experimental designs included A-B designs or a single-group design (Lang et al. 2012; Davis et al. 2013). Ten of the 12 included studies, involving a total of 138 participants, were classified as experimental [Studies 1, 2, 5–12]. Two studies, involving nine participants, were classified as quasi-experimental [Studies 3 and 4].

The experimental studies included the use of several types of single-case experimental designs [Studies 1, 2, 5, and 9]. For example, Studies 1 and 5 used an A-B-A-B design or modified A-B-A-B design, Study 2 used a multiple-baseline design, and Study 9 used an alternating treatments design with baseline and follow-up. The remaining experimental studies were randomized controlled trials, involving 74 participants [Studies 10 and 11], or a repeated-measures design with a control condition and counterbalancing [Studies 6, 7, 8, and 12], involving 54 participants. Study 3 was classified as quasi-experimental because it utilized a pre-post measure without a control group, and Study 4 was classified as quasi-experimental because it seemingly employed an A-B design, although it was unclear whether baseline data were collected.

Follow-Up and Generalization

Only one study reported follow-up data after implementation of the intervention [Study 9]. In this study, follow-up took place two weeks after the intervention had ended. Two follow-up sessions, one week apart, were conducted. Additionally, Study 1 stated that the music therapist followed up with the families of each of the participants three weeks after completion of the intervention to obtain verbal reports of occurrences of target behaviors. None of the studies reported measures of generalization; however, the third phase of Study 9 appeared to have included an element of generalization. Specifically, in Phase B, an alternating treatments intervention was introduced, alternating between play sessions with three toys, and musical play sessions with three other toys. In Phase C, the music sessions were continued, as these sessions appeared to be the more effective of the two treatments. At this stage, the toys from the Phase B play session were used in the music sessions to see whether the positive effects observed in the Phase B music sessions would still be evident with the use of the other toys.

Reliability of Data and Treatment Integrity

Most of the studies reported assessing reliability of data collection using inter-observer agreement measures [Studies 1, 2, 4–11]. Of the inter-rater reliability data reported, most were above the generally accepted standard of 80 % agreement. It was unclear whether inter-rater reliability was collected for Study 7, but the authors stated that a researcher and three reliability observers matched photographs to emotions, with a criterion set at .75 for a photograph to be coded as a correct response. Study 11 reported a procedure where inter-rater agreement between two raters was determined by using the study’s dependent variables to rate seven children who were not part of the study. Measures of inter-rater reliability would have been appropriate in the two remaining studies [Studies 3 and 12], but such data do not seem to have been collected.

Treatment integrity data were only reported in one study [Study 2] where teachers and peers were trained by the music therapist to implement a music intervention. The results were varied, but the study reported that most teachers and peers demonstrated a high level of treatment fidelity. Some studies described use of treatment protocols or guidelines [Studies 5, 6, 8, and 11].

Outcomes

Intervention outcomes were classified as positive, negative, or mixed, in accordance with the categories described by Lang et al. (2012). Seven of the studies (58 %), involving 99 of the total 147 participants (67 %), demonstrated positive outcomes [Studies 2, 5, 6, 8–10, 12]. In these studies, significant gains for the treatment condition were found, compared with the control group/condition, or visual analysis of data suggested improvement in all dependent variables for all participants for single-subject research designs. There were mixed results for the remaining five studies [Studies 1, 3, 4, 7, and 11], which involved a total of 48 participants.

Study 1 used an ABAB design. The intervention effects appeared positive from baseline to intervention; however, there was a failure to observe a reversal of trends in the second baseline for two of the three participants. In Study 3, significant improvements in dependent variables were observed for only some of the time periods. Study 4 demonstrated generally positive effects, but the results did not show one condition as consistently more effective than the other in the alternating treatment design. Generally, positive effects were also observed in Study 7; however, the intervention conditions did not show evidence of significantly greater improvement compared with control conditions. A further analysis revealed that once participants’ pre-test scores were taken into account, the intervention conditions appeared to be more effective than the control conditions. Similarly, Study 11 did not demonstrate a significant improvement in the experimental group compared with the control group, but a further analysis showed a statistically significant improvement for a subset of the participants. Only participants in the experimental group with diagnoses of autistic disorder (rather than PDD-NOS or Asperger’s disorder) showed significant improvement compared with the control group.

Certainty of Evidence

The certainty of evidence was rated as insufficient, preponderant, or conclusive in accordance with Davis et al.’s (2013) definitions. Seven of the studies provided conclusive evidence [Studies 2, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, and 11]. The majority of these were those that indicated positive outcomes (excluding Study 11). Three studies were rated as providing preponderant evidence [Studies 1, 7, and 12], and two studies were rated as providing insufficient evidence [Studies 3 and 4]. The preponderant ratings were due to the presence of confounding variables and possible carry-over effects [Study 1] and insufficient or absent inter-rater agreement data [Studies 7 and 12]. The two studies with insufficient evidence ratings were classified as such due to reliance on quasi-experimental designs. Study 3 employed a pre-post-test without a control group, while Study 4 employed what appeared to be an A-B design.

Discussion

Twelve studies evaluating the effects of music therapy for individuals with ASD were identified and analyzed in this systematic review. Our analysis of 12 studies indicated that most studies reported positive outcomes, suggesting that music therapy might be a promising intervention for some individuals with ASD and for some specific purposes. However, a number of limitations were revealed in this corpus of studies that warrant discussion.

In terms of scope, there were relatively few studies identified (n = 12). This review only appraised research since 2004 because Gold et al. (2006) had reviewed the literature prior to 2004. However, Gold et al.’s (2006) review included only group research designs and did not appraise studies using single-case research designs. The most up-to-date research that met inclusion criteria was published in 2011. It is unclear why there are not any more recently published data, although a study protocol for a proposed randomized controlled trial of improvisational music therapy for treatment of ASD was published in 2012 (Geretsegger et al. 2012).

A total of 147 individuals were represented in the identified studies. However, age range of participants was limited; eight of the studies included participants in the 3 to 5-year age range, while only one study focused on intervention for adults with ASD. This may be due, in part, to an emphasis on early intervention; however, more research on the effects of music therapy for older children, adolescents, and adults with ASD is needed. Another limitation is related to methodological quality. There is still a need for more rigorous, high-quality experimental research. The majority of studies failed to report treatment integrity data or include measures of generalization or maintenance.

Despite these methodological limitations, over half of the studies were of a sufficiently high standard to provide conclusive evidence. Positive outcomes were reported for 58 % of studies, while the remaining studies reported mixed outcomes. There were no studies reporting negative outcomes. Generally, positive outcomes were reported from studies that were mostly rated as capable of providing conclusive evidence, whereas studies reporting mixed outcomes generally had more procedural limitations.

Seven of the 12 studies focused on social interaction/social communication as the main intervention target [Studies 2, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12]. Other studies indirectly aimed to increase these behaviors; Studies 1 and 3 sought to decrease undesirable behaviors, thus promoting appropriate social interaction as alternative behavior. This supports the findings of Kaplan and Steele (2005) whose review of clinicians’ music therapy goals for individuals with ASD revealed that they were most likely to focus on improving communication and language, and promote behavioral and social skills.

As a considerable proportion of music therapy interventions for this population focused on increasing verbal and social communication, it would seem important to determine ASD severity, and indicate accompanying language impairments. A few studies reported on the severity of the symptoms of ASD [Studies 2, 5, 9, and 10], while two studies also specified whether participants were diagnosed with autistic disorder, PDD-NOS, or Asperger’s disorder [Studies 1 and 11]. With the release of The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM–5; American Psychiatric Association 2013), the former diagnoses of autistic disorder, PDD-NOS, Asperger’s disorder, and childhood disintegrative disorder have been collapsed into the single ASD category. Therefore, it may be particularly important to specify the severity of ASD. By doing so, further understanding may be gained about the impact of music therapy interventions for individuals with differing severity of ASD and language impairment.

The studies in this literature review primarily employed one of two music therapy approaches. These were the use of specific songs with lyrics related to target skills and the use of clinical improvisation. An analysis of intervention approach and study outcome revealed that both approaches were fairly equally spread across studies with positive results and studies with mixed results, suggesting that both approaches may be equally effective. However, there appears to be a paucity of research on other music therapy approaches that might be used with ASD populations, such as the use of structured musical activities, or songwriting and composition (see Wheeler et al. 2005). Future studies could investigate the effectiveness of these different approaches for individuals with ASD in different age ranges and with differing severity of ASD and language impairment.

At present, the results of this review point to an emerging evidence base on the effects of music therapy for individuals with ASD. Within this evidence base, there is sufficient conclusive evidence reporting positive outcomes to classify music therapy as a promising intervention for individuals with ASD. Positive outcomes have mainly been reported with respect to the frequency of verbal communication and social interaction. Because of its promise, additional research aimed at comparing music therapy to other forms of therapies for increasing communication and social skills would seem warranted. Studies evaluating the components responsible for, and the mechanism underlying, the promising effects of music therapy would also seem warranted.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the systematic review

Accordino, R., Comer, R., & Heller, W. B. (2007). Searching for music’s potential: a critical examination of research on music therapy with individuals with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 1, 101–115.

American Music Therapy Association (2014). Professional requirements for music therapists. Retrieved from http://www.musictherapy.org/about/requirements/

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author

*Boso, M., Emanuele, E., Minazzi, V., Abbamonte, M., & Politi, P. (2007). Effect of long-term interactive music therapy on behavior profile and music skills in young adults with severe autism. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 13, 709–712. doi:10.1089/acm.2006.6334

Bruscia, K. E. (1998). Defining music therapy (2nd ed.). Barcelona: Gilsum NH.

Cohen, I. L., & Sudhalter, V. (1999). Pervasive Developmental Disorder Behavior Inventory (PDDBI-C). NYS Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities.

Davis, T. N., O’Reilly, M., Kang, S., Lang, R., Rispoli, M., Sigafoos, J., ... Mulloy, A. (2013). Chelation treatment for autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7, 49–55.

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, L. M. (1997). Peabody picture vocabulary test (3rd ed.). Circle Pines: American Guidance Service.

Edelson, M. G. (2006). Are the majority of children with autism mentally retarded? A systematic evaluation of the data. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities, 21, 66–83.

*Finnigan, E., & Starr, E. (2010). Increasing social responsiveness in a child with autism: a comparison of music and non-music interventions. Autism, 14, 321–348. doi:10.1177/1362361309357747

Gardner, M. F. (2000a). Expressive one-word picture vocabulary test. Novato: Academic Therapy Publications.

Gardner, M. F. (2000b). Receptive one-word picture vocabulary test. Novato: Academic Therapy Publications.

*Gattino, G. S., Riesgo, R. D. S., Longo, D., Leite, J. C. L., & Faccini, L. S. (2011). Effects of relational music therapy on communication of children with autism: a randomized controlled study. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 20, 142–154. doi:10.1080/08098131.2011.566933.

Geretsegger, M., Holck, U., & Gold, C. (2012). Randomised controlled trial of improvisational music therapy’s effectiveness for children with autism spectrum disorders (TIME-A): study protocol. BMC Pediatrics. doi:10.1186/1471-2431-12-2.

Geschwind, D. H. (2009). Advances in autism. Annual Review of Medicine, 60, 367–380.

Gold, C., Wigram, T., & Elefant, C. (2006). Music therapy for autistic spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004381.pub2.

Gray, C. A., & Garand, J. D. (1993). Social stories: improving responses of students with autism with accurate social information. Focus on Autistic Behavior, 8, 1–10.

Green, V. A., Pituch, K. A., Itchon, J., Choi, A., O’Reilly, M., & Sigafoos, J. (2006). Internet survey of treatments used by parents of children with autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 27, 70–84.

Grocke, D. E., & Wheeler, B. L. (2001). Information sharing: report from the World Federation of Music Therapy commission on education, training, and accreditation education symposium. Music Therapy Perspectives, 19, 63–67.

Guy, W. (Ed.). (1976). ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology (pp. 76–338). Washington, DC: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

Horovitz, M., Matson, J. L., & Sipes, M. (2011). The relationship between parents’ first concerns and symptoms of autism spectrum disorders. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 14, 372–377.

Kaplan, R. S., & Steele, A. L. (2005). An analysis of music therapy program goals and outcomes for clients with diagnoses on the autism spectrum. Journal of Music Therapy, 42, 2–19.

*Katagiri, J. (2009). The effect of background music and song texts on emotional understanding of children with autism. Journal of Music Therapy, 46, 15–31.

*Kern, P., & Aldridge, D. (2006). Using embedded music therapy interventions to support outdoor play of young children with autism in an inclusive community-based child care program. Journal of Music Therapy, 43, 270–294.

*Kern, P., Wakeford, L., & Aldridge, D. (2007a). Improving the performance of a young child with autism during self-care tasks using embedded song interventions: a case study. Music Therapy Perspectives, 25, 43–51.

*Kern, P., Wolery, M., & Aldridge, D. (2007b). Use of songs to promote independence in morning greeting routines for young children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1264–1271. doi:10.1007/s10803-006-0272-1

*Kim, J., Wigram, T., & Gold, C. (2008). The effects of improvisational music therapy on joint attention behaviors in autistic children: a randomized controlled study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1758–1766. doi:10.1007/s10803-008-0566-6

*Kim, J., Wigram, T., & Gold, C. (2009). Emotional, motivational and interpersonal responsiveness of children with autism in improvisational music therapy. Autism, 13, 389–409. doi:10.1177/1362361309105660

Lang, R., O’Reilly, M., Healy, O., Rispoli, M., Lydon, H., Streusand, W., ... Giesbers, S. (2012). Sensory integration therapy for autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 1004–1018.

Lang, R., Regester, A., Lauderdale, S., Ashbaugh, K., & Haring, A. (2010). Treatment of anxiety in autism spectrum disorders using cognitive behavior therapy: a systematic review. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 13, 53–63.

*Lim, H. A. (2010a). Effect of “developmental speech and language training through music” on speech production in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Music Therapy, 47, 2–26.

Lim, H. A. (2010b). Use of music in the applied behavior analysis verbal behavior approach for children with autism spectrum disorders. Music Therapy Perspectives, 28, 95–105.

*Lim, H. A., & Draper, E. (2011). The effects of music therapy incorporated with applied behavior analysis verbal behavior approach for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Music Therapy, 48, 532–550.

Mirenda, P. (2008). A back door approach to autism and AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 24, 220–234.

Mudford, O. C., & Cullen, C. (2005). Auditory integration training: a critical review. In J. W. Jacobsen, R. M. Foxx, & J. A. Mulick (Eds.), Controversial therapies for developmental disabilities: Fad, fashion, and science in professional practice (pp. 351–362). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Mundy, P., Delgado, C., Block, J., Venezia, M., Hogan, A. & Seibert, J. (2003). A manual for the abridged Early Social Communication Scales (ESCS). University of Miami

*Pasiali, V. (2004). The use of prescriptive therapeutic songs in a home-based environment to promote social skills acquisition by children with autism: three case studies. Music Therapy Perspectives, 22, 11–20

Pereira, A., Riesgo, R. S., & Wagner, M. B. (2008). Childhood autism: translation and validation of the childhood autism rating scale for use in Brazil. Jornal de Pediatria, 84, 487–494.

Prizant, B. M. (1996). Brief report: communication, language, social and emotional development. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 26, 173–178.

Reschke-Hernández, A. E. (2011). History of music therapy treatment interventions for children with autism. Journal of Music Therapy, 48, 169–207.

Rutter, M., Le Couteur, A., & Lord, C. (1994). Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24, 659–685.

Schlosser, R. W., & Wendt, O. (2008). Effects of augmentative and alternative communication intervention on speech production in children with autism: a systematic review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17, 212–230.

Schopler, E., Reichler, R. J., & Renner, B. R. (1988). Childhood Autism Rating Scale. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Schopler, E., Reichler, R., & Rochen Renner, B. (1998). Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Sigafoos, J., Green, V. A., Schlosser, R., O’Reilly, M. F., Lancioni, G. E., Rispoli, M., & Lang, R. (2009). Communication intervention in Rett syndrome: a systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3, 304–318.

Thaut, M. H. (2005). Rhythm, music, and the brain: scientific foundations and clinical applications. New York: Routledge.

Ventura, J., Green, M. F., Shaner, A., & Liberman, R. P. (1993). Training and quality assurance with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: the drift busters. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 3, 221–244.

Wheeler, B. L., Shultis, C. L., & Polen, D. W. (2005). Clinical training guide for the student music therapist. Barcelona: Gilsum.

Wigram, T., & Gold, C. (2006). Music therapy in the assessment and treatment of autistic spectrum disorder: clinical application and research evidence. Child: Care, Health and Development, 32, 535–542.

Wigram, T., Pedersen, I. N., & Bonde, L. O. (2002). A comprehensive guide to music therapy: theory, clinical practice, research and training. London: Jessica Kingsley.

World Federation of Music Therapy (2011). What is music therapy? Retrieved from http://www.wfmt.info/WFMT/Info_Cards_files/ENGLISH%20-%20NEW%20What%20is%20music%20therapy.pdf

Zimmerman, I. L., Steiner, V. G., & Pond, R. E. (2006). Preschool language skill (4th ed.). San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation/Harcourt Brace.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Excluded Studies [and reason for exclusion]

Gadberry, A. L. (2012). Client communicative acts and therapist prompts with and without aided augmentative and alternative communication systems. Music Therapy Perspectives, 30, 151–157. [Not focused on determining the effect of music therapy intervention compared with control].

Hillier, A., Greher, G., Poto, N., & Dougherty, M. (2011). Positive outcomes following participation in a music intervention for adolescents and young adults on the autism spectrum. Psychology of Music, 40, 201–215. doi:10.1177/0305735610386837 [Not classified as a music therapy intervention].

Kalas, A. (2012). Joint attention responses of children with autism spectrum disorder to simple versus complex music. Journal of Music Therapy, 49, 430–452. [Not focused on determining the effect of music therapy intervention compared with control].

Kern, P. (2004). Using a music therapy collaborative consultative approach for the inclusion of young children with autism in a childcare program. (Doctoral thesis, University of Witten-Herdecke, Witten, Germany). Retrieved from http://www.wfmt.info/Musictherapyworld/modules/archive/dissertations/pdfs/Diss_2004_Petra_Kern.pdf [Duplication of Studies 2, 4, and 5].

Raglio, A., Traficante, D., & Oasi, O. (2011). Autism and music therapy: intersubjective approach and music therapy assessment. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 20, 123–141. doi:10.1080/08098130903377399 [Theoretical and descriptive article].

Sandiford, G. A., Mainess, K. J., & Daher, N. S. (2013). A pilot study on the efficacy of melodic based communication therapy for eliciting speech in nonverbal children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 1298–1307. doi:10.1007/s10803-012-1672-z [Not classified as a music therapy intervention].

Stephens, C. E. (2008). Spontaneous imitation by children with autism during a repetitive musical play routine. Autism, 12, 645–671. doi:10.1177/1362361308097117 [Not classified as a music therapy intervention].

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

James, R., Sigafoos, J., Green, V.A. et al. Music Therapy for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Systematic Review. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 2, 39–54 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-014-0035-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-014-0035-4