Abstract

The phase III, randomized, open-label CheckMate 025 study showed an overall survival benefit in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab versus everolimus. Here, we review the health-related quality of life (HRQoL) results of this trial, in which nivolumab was associated with significant improvements in HRQoL, with more patients having a clinically meaningful HRQoL improvement and a shorter time to onset of improvement compared with everolimus. Further exploratory analysis suggests a positive correlation between baseline HRQoL scores and overall survival. These results support the use of HRQoL as a valuable measure of patient perspective that could translate into better clinical outcomes and should be taken into account during treatment selection.

Similar content being viewed by others

In cancer, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a composite indicator of tumor symptoms and adverse events (AEs) from treatment that may reveal differences in patients’ perceptions of tolerability that are not captured from standard AE reporting measures. In metastatic renal cell carcinoma, for example, studies of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) in the first-line setting have demonstrated the important effect that differing AE profiles can have on patient preferences for treatments. In the COMPARZ study, patient perceptions of greater fatigue, mouth/throat soreness, and foot soreness with sunitinib versus pazopanib were consistent with physician-assessed AEs and associated with lower treatment satisfaction [1]. However, in the PISCES study, significantly more patients preferred pazopanib over sunitinib (70% vs. 22%; P < 0.001) despite an equal or worse incidence of AEs. Better HRQoL was commonly cited by patients as a reason for preferring pazopanib. Patient preference was consistent with physician preference (61% vs. 22%) [2]. These results suggest that perceptions of HRQoL are multifaceted and subjective, and cannot be captured by incidence and severity of individual AEs—possibly because of individual variations in frequency and severity, and because of differences in patients’ perceptions of the relevance of certain AEs. While physicians tend to focus on more serious AEs, these studies illustrate the importance of low-grade AEs and their perception for patients’ HRQoL.

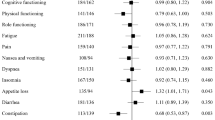

A comparison of the effects on HRQoL of an immune checkpoint programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitor (nivolumab) with the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor everolimus in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma has recently been published [3]. CheckMate 025 was a robustly designed study comparing nivolumab and everolimus in a large patient population (n = 821) with renal cell carcinoma who had received prior antiangiogenic therapy [4]. All procedures followed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before they were included in the study. The primary endpoint of the study was overall survival; secondary endpoints included the objective response rate, progression-free survival, and safety. The minimum follow-up period was 14 months. Median overall survival was 25.0 months [95% confidence interval (CI) 21.8–not reached] in the nivolumab group and 19.6 months (95% CI 17.6–23.1) in the everolimus group [hazard ratio (HR) 0.73; 98.5% CI 0.57–0.93; P = 0.002]. The objective response rate was higher with nivolumab than with everolimus (25% vs. 5%; odds ratio 5.98; 95% CI 3.68–9.72; P < 0.001). Median progression-free survival was 4.6 months (95% CI 3.7–5.4) in the nivolumab group and 4.4 months (95% CI 3.7–5.5) in the everolimus group (HR, 0.88; 95% CI 0.75–1.03; P = 0.11). The incidence of treatment-related AEs was lower in the nivolumab group (79%) compared with the everolimus group (88%) [4]. HRQoL was assessed using the nine-item Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Kidney Symptom Index–Disease-Related Symptoms (FKSI-DRS) questionnaire that measures symptoms predominantly related to kidney cancer (energy, pain, weight loss, bone pain, fatigue, dyspnea, cough, fevers, and hematuria) [3]. The study had high HRQoL questionnaire completion rates (86–89%). Nivolumab was associated with significant improvement in HRQoL that began in week 20 and lasted the duration of the study. Compared with everolimus, the change from baseline to week 84 was statistically significant and observed in all items of the FKSI-DRS except bone pain [4]. More patients had a clinically meaningful HRQoL improvement with nivolumab compared with everolimus (55% vs. 37%, respectively), and the time to onset of improvement was shorter with nivolumab [3]. Although the open-label nature of the study could have induced a biased response, this seems unlikely to have been a major factor, given that the effects were long-lasting. In addition, the relationship between the clinical response and quality of life (QoL) components is complex, in part because the latter, being a patient-reported outcome (PRO), reflects subjective differences in the individual reports of changes in HRQoL.

The improvement observed with nivolumab compared with everolimus in CheckMate 025 is notable, given the efficacy and safety profile of everolimus in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma [4]. Furthermore, the QoL improvement with nivolumab was linked to improvements in clinical outcomes, which suggests that the effect is associated with treatment efficacy rather than the absence of TKI-related AEs. An exploratory analysis showed a positive correlation between baseline HRQoL scores and overall survival [3], and tumor responses with nivolumab tended to occur before HRQoL improvements: the median time to tumor response was 3.5 months (range 1.4–24.8), while the time to HRQoL response was 4.7 months (95% CI 3.7–7.5) [3, 4]. However, the magnitude of the effect suggests that patients treated with nivolumab experience greater treatment benefit than might be expected on the basis of the objective tumor response rate.

The study also found that baseline QoL has prognostic value. Conventionally, a patient’s prognosis is determined through a review of clinical parameters, as exemplified by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center prognostic criteria. These results suggest that a patient’s reported QoL provides additional information that may allow a more accurate estimate of prognosis. It is noteworthy, however, that nivolumab was associated with better clinical outcomes than everolimus (except for progression-free survival), regardless of baseline HRQoL [3].

The HRQoL instruments used in this study are the current mainstay for the assessment of QoL, although the therapeutic landscape has changed considerably since they were developed. The PRO version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE) is a recently developed instrument that employs a flexible, fit-for-purpose approach to assess the frequency of, severity of, and interference from symptomatic treatment-associated toxicities [5]. While the applicability and validity of newer tools such as the PRO-CTCAE are yet to be established for treatment with TKIs or immune checkpoint blockade, they may be used in future studies. Nevertheless, existing tools still capture the benefit of novel agents, as demonstrated by the CheckMate 025 QoL results.

Conclusions

Tolerability is an increasingly important aspect of renal cell carcinoma management, as patients are living longer due to efficacy advantages of modern treatments. HRQoL data provide an overall assessment of the patient-centered impact of treatment-related AEs, and the rapid and sustained HRQoL benefits of nivolumab reflect reduced treatment-related toxicity. This, and the higher number of patients with a clinically meaningful HRQoL response with nivolumab compared with everolimus, strengthens and supports observations of improved clinical outcomes.

References

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, Reeves J, Hawkins R, Guo J, Nathan P, Staehler M, de Souza P, Merchan JR, Boleti E, Fife K, Jin J, Jones R, Uemura H, De Giorgi U, Harmenberg U, Wang J, Sternberg CN, Deen K, McCann L, Hackshaw MD, Crescenzo R, Pandite LN, Choueiri TK. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:722–31.

Escudier B, Porta C, Bono P, Powles T, Eisen T, Sternberg CN, Gschwend JE, De Giorgi U, Parikh O, Hawkins R, Sevin E, Négrier S, Khan S, Diaz J, Redhu S, Mehmud F, Cella D. Randomized, controlled, double-blind, cross-over trial assessing treatment preference for pazopanib versus sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: PISCES Study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1412–8.

Cella D, Grünwald V, Nathan P, Doan J, Dastani H, Taylor F, Bennett B, DeRosa M, Berry S, Broglio K, Berghorn E, Motzer RJ. Quality of life in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma given nivolumab versus everolimus in CheckMate 025: a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17:994–1003.

Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, George S, Hammers HJ, Srinivas S, Tykodi SS, Sosman JA, Procopio G, Plimack ER, Castellano D, Choueiri TK, Gurney H, Donskov F, Bono P, Wagstaff J, Gauler TC, Ueda T, Tomita Y, Schutz FA, Kollmannsberger C, Larkin J, Ravaud A, Simon JS, Xu LA, Waxman IM, Sharma P, CheckMate 025 Investigators. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1803–13.

Dueck AC, Mendoza TR, Mitchell SA, Reeve BB, Castro KM, Rogak LJ, Atkinson TM, Bennett AV, Denicoff AM, O’Mara AM, Li Y, Clauser SB, Bryant DM, Bearden JD 3rd, Gillis TA, Harness JK, Siegel RD, Paul DB, Cleeland CS, Schrag D, Sloan JA, Abernathy AP, Bruner DW, Minasian LM, Basch E, National cancer Institute PRO-CTCAE Study Group. Validity and reliability of the US National Cancer Institute’s Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE). JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:1051–9.

Acknowledgements

The CheckMate 025 study and this article’s processing charges were also funded by Bristol–Myers Squibb GmbH & Co. KGaA.

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Professional medical writing support was provided by Juan Sanchez-Cortes, PhD, of PPSI (a PAREXEL Company), funded by Bristol–Myers Squibb GmbH & Co. KGaA.

Disclosures

Marc-Oliver Grimm received advisory/consultation fees from Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Bristol–Myers Squibb (BMS), GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Pfizer and speaker honoraria from BMS, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Pfizer. Viktor Grünwald received consultation fees from BMS, Novartis, Pfizer, and Bayer; speaker honoraria from BMS, Novartis, and Pfizer; and travel/accommodation support from BMS, Novartis, Pfizer, MSD, and Merck KGaA.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures followed in CheckMate 025 were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before they were included in the study.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to www.medengine.com/Redeem/73F7F0606CAF7DFF.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Grimm, MO., Grünwald, V. Health-Related Quality of Life as a Prognostic Measure of Clinical Outcomes in Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Review of the CheckMate 025 Trial. Oncol Ther 5, 75–78 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-017-0042-6

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40487-017-0042-6