Abstract

Background

Point of care ultrasound (POCUS) is a useful diagnostic tool in medicine. POCUS provides an easy and reproducible method of diagnosis where conventional radiologic studies are unavailable. Telemedicine is also a great means of communication between educators and students throughout the world.

Hypothesis

Implementing POCUS with didactics and hands-on training, using portable ultrasound devices followed by telecommunication training, will impact the differential diagnosis and patient management in a rural community outside the United States.

Materials and methods

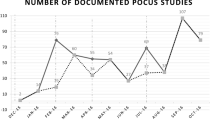

This is an observational prospective study implementing POCUS in Las Salinas, a small village in rural western Nicaragua. Ultrasound was used to confirm a diagnosis based on clinical exam, or uncover a new, previously unknown diagnosis. The primary endpoint was a change in patient management. International sonographic instructors conducted didactic and practical training of local practitioners in POCUS, subsequently followed by remote guidance and telecommunication for 3 months.

Results

A total of 132 patients underwent ultrasound examination. The most common presentation was for a prenatal exam (23.5 %), followed by abdominal pain (17 %). Of the 132 patients, 69 (52 %) were found to have a new diagnosis. Excluding pregnancy, 67 patients of 101 (66 %) were found to have a new diagnosis. A change in management occurred in a total of 64 (48 %) patients, and 62 (61 %) after excluding pregnancy.

Conclusion

Implementing POCUS in rural Nicaragua led to a change in management in about half of the patients examined. With the appropriate training of clinicians, POCUS combined with telemedicine can positively impact patient care.

Sommario

Background

La diagnostica ecografica (POCUS) é un utile strumento diagnostico in medicina. Fornisce un metodo semplice e riproducibile di diagnosi, dove studi radiologici convenzionali non siano disponibili. Anche la telemedicina é un grande mezzo di comunicazione tra docenti e studenti di tutto il mondo.

Ipotesi

L’implementazione della POCUS con formazione didattica diretta, utilizzando ecografi portatili, seguita da una formazione attraverso la telecomunicazione, avrà un impatto nella diagnosi differenziale e nella gestione del paziente in una comunità rurale fuori degli Stati Uniti.

Materiali e Metodi

Presentiamo uno studio prospettico sull’implementazione della POCUS a Las Salinas, un piccolo villaggio rurale del Nicaragua occidentale. L’ecografia è stata utilizzata per confermare la diagnosi clinica, o per nuove diagnosi. Il punto primario era un cambiamento nella gestione del paziente. Istruttori internazionali hanno condotto una formazione didattica pratica locale, poi seguita da una guida a distanza con telecomunicazione, per tre mesi.

Risultati

Un totale di 132 pazienti sono stati sottoposti ad esame ecografico. L’esame più comune era per la diagnostica prenatale (23,5 %), seguito dal dolore addominale (17 %). Dei 132 pazienti, 69 (52 %) hanno avuto una nuova diagnosi. Nella diagnosi di esclusione di gravidanza 67 pazienti su 101 (66 %) hanno avuto una nuova diagnosi. Un cambiamento nella gestione si è verificato in un totale di 64 (48 %) pazienti, e in 62 (61 %) dopo aver escluso la gravidanza.

Conclusione

L’implementazione della POCUS nelle zone rurali del Nicaragua ha portato ad un cambiamento di gestione in circa la metà dei pazienti esaminati. Con la formazione adeguata dei medici, la POCUS, combinata con la telemedicina, può avere un impatto positivo nella cura del paziente.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Langlois S (2007) Focused ultrasound training for clinicians. Crit Care Med 35(5):S138–S143

Evans N, Gournay V, Cabanas F et al (2001) Point-of-care ultrasound in the neonatal intensive care unit: international perspectives. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 16(1):61–68

Vieira RL, Hsu D, Nagler J et al (2013) Pediatric emergency medicine fellow training in ultrasound: consensus educational guidelines. Acad Emerg Med 20(3):300–306

Dulchavsky SA, Henry SE, Diebel LN (2002) Advanced ultrasonic diagnosis of extremity trauma: the FASTER examination. J Trauma 53(1):28–32

Hile DC, Morgan AR, Laselle BT, Bothwell JD (2012) Is point-of-care ultrasound accurate and useful in the hands of military medical technicians? A review of the literature. Mil Med 177(8):983–987

Royse CF, Canty DJ, Faris J et al (2012) Core review: physician-performed ultrasound: the time has come for routine use in acute care medicine. Anesth Analg 115(5):1007–1028

Cohen JS, Teach SJ, Chapman JI (2012) Bedside ultrasound education in pediatric emergency medicine fellowship programs in the United States. Pediatr Emerg Care 28(9):845–850

Emergency Ultrasound Fellowship Programs. 2013. http://www.eusfellowships.com/programs.php. Accessed 1 June 2014

Mandavia DP, Aragona J, Chan L et al (2000) Ultrasound training for emergency physicians—A prospective study. Acad Emerg Med 7:1008–1014

Hoppman R, Rao V, Poston MB et al (2011) An integrated ultrasound curriculum (iUSC) for medical students: 4-year experience. Crit Ultrasound J 3(1):1–12

Swamy M, Searle RF (2012) Anatomy teaching with portable ultrasound to medical students. BMC Med Educ 22(12):99

Mouratev G, Howe D, Hoppmann R et al (2013) Teaching medical students ultrasound to measure liver size: comparison with experienced clinicians using physical examination alone. Teach Learn Med 25(1):84–88

Chin EJ, Chan CH, Mortazavi R et al (2013) A pilot study examining the viability of a Prehospital Assessment with Ultrasound for Emergencies (PAUSE) protocol. J Emerg Med 44(1):142–149

Shah S, Noble VE, Umulisa I et al (2008) Development of an ultrasound training curriculum in a limited resource international setting: successes and challenges of ultrasound training in rural Rwanda. Int J Emerg Med 1(3):193–196

Kimberly HH, Murray A, Mennicke M et al (2010) Focused maternal ultrasound by midwives in rural Zambia. Ultrasound Med Biol 36(8):1267–1272

Kendall JL, Hoffenberg SR, Smith RS (2007) History of emergency and critical care ultrasound: the evolution of a new imaging paradigm. Crit Care Med 35(5):S126–S130

Alajmi D, Almansour S, Househ MS (2013) Recommendations for implementing telemedicine in the developing world. Stud Health Technol Inform 190:118–120

Marchburn TH, Hadfield CA, Sargsyan AE et al (2014) New heights in ultrasound: first report of spinal ultrasound from the international space station. J Emerg Med 46(1):61–70

Killu K, Dulchavsky S, Coba V (2010) The ICU ultrasound pocket book. Medical Imagineering 2010, iTunes, Rochester, NY

Neri L, Storti E, Lichtenstein D (2007) Towards ultrasound training curriculum for critical care medicine. Crit Care Med 35(5):S290–S304

Tanzola RC, Walsh S, Hopman WM et al (2013) Brief report: focused transthoracic echocardiography training in a cohort of Canadian anesthesiology residents: a pilot study. Can J Anaesth 60(1):32–37

Price S, Via G, Sloth E et al (2008) Echocardiography, practice, training and accreditation in the intensive care: document for the World Interactive Network Focused on Critical Ultrasound (WINFOCUS). Cardiovasc Ultrasound 6:49

Blaivas M, Kuhn W, Reynolds B, Brannam L (2005) Change in differential diagnosis and patient management with the use of portable ultrasound in a remote setting. Wilderness Environ Med 16(1):38–41

Conlon R (2012) Teaching ultrasound in tropical countries. J Ultrasound 15(3):144–150

Conflict of interest

The authors on this manuscript have no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. All patients provided written informed consent to enrollment in the study and to the inclusion in this article of information that could potentially lead to their identification.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kolbe, N., Killu, K., Coba, V. et al. Point of care ultrasound (POCUS) telemedicine project in rural Nicaragua and its impact on patient management. J Ultrasound 18, 179–185 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40477-014-0126-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40477-014-0126-1