Abstract

Purpose of Review

CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing holds promise for the future correction of congenital defects in vivo, providing potentially curative interventions for numerous intractable diseases. Nevertheless, the bacterial origin of the Cas9 endonuclease raises the spectre of pre-existing immunity that threatens to undermine the success of this powerful technology, necessitating a careful assessment of the potential risks involved.

Recent Findings

Given that genome editing commonly exploits the specificity of Cas9 endonucleases from species of bacteria that are a common cause of infection in humans, the recent discovery of neutralising antibodies in the sera of healthy individuals is consistent with pre-existing immunity. Furthermore, the demonstration of T cell responses to Cas9 epitopes suggests that cells and tissues successfully targeted for correction of congenital mutations may be rendered vulnerable to cytotoxic T cell lysis, potentially confounding any future benefits to human health.

Summary

Although the full impact of pre-existing immunity to Cas9 on the success of in vivo genome editing has yet to be fully determined, it is timely to discuss ways of evading destructive immunity to ensure that its future potential is fully realised.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Heralded by Science as its breakthrough of the year 2015 [1], the discovery of the clustered regularly interspaced palindromic sequences (CRISPR)-Cas9 system for genome editing offers a new age in humanity’s interaction with its own genetic code. By offering opportunities for the introduction of subtle changes directly into the genome, CRISPR-Cas9 has already proven to be a powerful tool for the generation of novel animal models of human disease [2,3,4] and, controversially, the genetic modification of human embryos [5•], culminating in the widely condemned birth of twins in China rendered immune to HIV-1 infection [6]. While such misuse of a promising technology continues to attract most attention, a far more important application may involve the development of therapies for human illnesses, such as sickle cell anaemia and Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy (DMD) that traditionally have been intractable to treatment: indeed, various clinical trials for cancer immunotherapy are currently underway, the majority based in China, which exploit the capacity for ex vivo editing of cells using CRISPR-Cas9 and their re-administration to patients, suggesting that a revolution in genome editing continues to gather pace [7, 8].

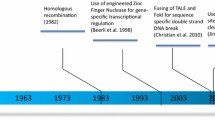

CRISPR-Cas9 represents the latest in a long line of tools for editing the human genome that have included zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) and TAL effector nucleases (TALENs), but is undoubtedly the most rapid and efficient method of genome editing developed so far (reviewed in [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]). The system derives from a primitive form of adaptive immunity found in numerous species of bacteria and archaea, which is based around a means for archiving short sequences of foreign phage DNA at the CRISPR loci. When transcribed, these sequences serve as antisense RNA guides that provide a record of past infections with bacteriophages and, when complexed with Cas proteins, can recognise and cleave foreign genetic material of the same origin upon subsequent infection [16]. The capacity to introduce double-strand breaks at specific locations within target DNA has been adapted for the purpose of genome editing of mammalian cells through the design of a short oligonucleotide complementary to the target sequence. So-called single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) are composed of a 20-nucleotide sequence at the 5′ end that confers specificity and a double-stranded structure at the 3′ end that interacts directly with the Cas9 nuclease. The ability to introduce a targeted DNA double-strand break may be exploited for the insertion or deletion of sequences or the correction of deleterious mutations through the provision of an exogenous DNA donor repair template which may be incorporated through homology-directed repair (HDR) pathways. Given that exquisite specificity may be conferred by sgRNAs that are straightforward to synthesise, the CRISPR-Cas9 system has significant advantages over other gene editing tools, such as the ZFNs, which require substantial protein engineering to confer a similar level of specificity [16].

In an effort to fully hone the utility of CRISPR-Cas9 for use in clinical trials, most progress has been made in the areas of specificity, delivery and efficacy [17]. Efforts to create a high-fidelity Cas9 enzyme and Cas9-directed base editors have already increased efficacy of genome editing and reduced the incidence of potentially deleterious off-target effects [18••]. However, other challenges may ultimately derail the upward trajectory of such a powerful development, including unexpected interference from the immune system of the recipient. Since Cas9 is a protein of microbial origin with orthologs across many species including the common human pathogens Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) and Staphylococcus aureus (SaCas9), it is conceivable that there is widespread pre-existing immunity throughout the human population. It has been estimated, for instance, that at any time, as many as 40% of people are colonised by S. aureus [19] while approximately 12% of children under 18 may harbour asymptomatic infections of S. pyogenes which, under certain circumstances, may become opportunistic, resulting in pharyngitis or pyoderma. Such routine exposure to the organisms from which Cas9 is commonly derived has led to the screening of healthy individuals for hallmarks of immunity that might confound attempts to exploit the unique properties of this nuclease for therapeutic purposes.

Evidence of Humoral Immunity to Cas9

The first evidence of humoral immunity to Cas9 was suggested in a seminal study by Wang and colleagues in which CRISPR-Cas9 was used to disrupt Pten gene expression in the hepatocytes of mice, thereby creating an effective model of human non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) [2]. Although genome editing was successfully achieved, the authors observed SpCas9-specific antibodies of the IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b isotypes 14 days later, findings that have since been independently verified [2, 20], confirming the immunogenicity of the enzyme. In these studies, the CRISPR-Cas9 system was delivered via adeno-associated viral vectors (AAV), preferred for their serological compatibility with a large proportion of the human population, their lack of pathogenicity and capacity for a semi-selective biodistribution [2]. Given that this approach elicited humoral responses, despite delivering the genes encoding SpCas9 directly to the target cells, it might be anticipated that the injection of pre-assembled SpCas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes into the circulation would have a far higher likelihood of eliciting primary responses or succumbing to neutralisation by pre-existing antibodies. While these findings might caution against such a mode of delivery, the direct i.v. administration of the genome editing machinery was recently favoured by Sangamo Therapeutics in a groundbreaking trial for the treatment of Hunter’s syndrome, albeit using ZFNs rather than CRISPR-Cas9 RPN complexes. Furthermore, the direct injection of SpCas9-sgRNA complexes into the tail veins of mice has been shown to correctly target hepatocytes at a frequency of 1/250 cells [4]. This efficacy might be significantly improved with the use of Cas9 orthologs from thermophiles such as Geobacillus stearothermophilus displaying significantly greater stability in human plasma compared to SpCas9, which is rapidly inactivated [21•]. Furthermore, as demonstrated by Wang and colleagues [2], the delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 via viral vectors does not preclude the induction of humoral responses to the Cas9 cargo: indeed, immunogenicity is arguably exacerbated by additional responses directed to the viral vectors which might serve the role of an adjuvant, providing multiple levels of potential sabotage. Consequently, it may yet prove premature to dismiss the direct i.v. administration of RNP complexes as a mode of delivery, raising questions as to whether Cas9 might induce similar responses in man as observed in mouse models.

Theoretical approaches to this question support the potential for humoral immunity to Cas9 in humans. Phage display may uncover potential conformational epitopes by examining mimotopes which model certain 3D features of Cas9, while computer modelling offers an alternative route to the prediction of epitopes of the protein. Although it has been shown that systems which predict B cell epitopes have limited specificity and accuracy [22, 23], several conformational epitopes for SpCas9, SaCas9 and Cas9 from Campylobacter jejuni (CjCas9) have already been identified [24] using the DiscoTope2.0 [25] and the ElliPro [26] systems. These findings suggest that prior exposure to common human pathogens such as S. aureus and S. pyogenes should not be dismissed lightly as having the potential to derail efforts for genome editing in vivo.

This issue was addressed directly in a widely publicised study by Porteus and colleagues, published on a pre-print server in January 2018 that has yet to be peer reviewed. The study analysed cord blood from 22 donors and sera from 12 healthy adults and reported the presence of antibodies against SpCas9 and SaCas9 in 79% and 65% of samples respectively [27]. Accessing a far larger cohort of 200 human sera, Simhadri et al. subsequently reported similar findings, although only 10% of donors were found to be seropositive for SaCas9 and 2.5% for SpCas9 [28••], such differences in frequency compared to previous estimates most likely being attributable to the sample size involved and the use of an ELISA as a readout, in preference to Western blotting. This suggests that the human immune system is routinely exposed to and mounts an immune response against these two homologues of Cas9 generating antibodies that could bind directly to the active site of the enzyme, sterically hindering interactions with the target DNA, or form immune complexes that would be actively cleared from the circulation. Although it might be argued that testing seropositive for neutralising antibodies to Cas9 might constitute an important criterion for exclusion from clinical trials of gene therapy, the high proportion of the population to which this might apply might prompt its re-assessment.

Evidence for Cellular Immunity to Cas9

Whereas the delivery of genes encoding Cas9 via viral vectors may help reduce the impact of humoral immunity on the efficacy of genome editing, transient expression of the nuclease in correctly targeted cells would be expected to result in presentation of proteasome-spliced epitopes via HLA class I, potentially attracting the attention of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). Computer algorithms have been developed to identify potential epitopes of Cas9 based on the assumption that the higher the affinity of a peptide for the binding groove of MHC molecules, the greater the likelihood of peptide presentation and a subsequent T cell response [29,30,31]. Whereas such algorithms are reasonably accurate with certain HLA haplotypes [32], for others, the algorithm does not perform as well [33]. Nevertheless, such models predict that the Cas9 protein contains many peptide sequences which may bind to common HLA class I and class II determinants.

That cell-mediated immunity might pose a significant threat to the integrity of genetically modified cells was recently supported by the findings of Wagner and colleagues who demonstrated pre-existing effector T cells specific for SpCas9 in healthy individuals [18••]. Challenging peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) in vitro with recombinant SpCas9 revealed 96% of donors to be capable of responding with an effector T cell response involving the secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-2. Significantly, responding cells displayed an effector memory phenotype consistent with repetitive previous exposure to SpCas9. Furthermore, no such responses were obtained when using T cells purified from cord blood which would not be anticipated to show evidence of prior exposure to S. pyogenes infection. Similar findings were reported for SaCas9 by Charlesworth et al. [27] who showed that 46% of human peripheral blood samples contained antigen-specific CD4+ Th1 cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, although, curiously, none specific for SpCas9 could be detected.

The relevance of these findings might be questioned, however, by a number of studies in animal models. For instance, Amoasii and colleagues successfully performed genome editing in a canine model of DMD but found little CD4+ or CD8+ T cell infiltration 6 weeks after intramuscular delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 via AAV or 8 weeks after systemic administration [34]. In contrast, Chew et al. showed both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses to Cas9 delivered to mice via AAV9 [20]. Targeted muscles showed infiltration of CD45+ cells, enriched for T cells and cells of myeloid origin, which were preferentially localised around transgene-expressing myofibres: delivery of the same vectors without the Cas9 coding sequence failed to elicit infiltration. Nevertheless, T cell infiltration caused little detectable cellular damage, suggesting that the CTL displayed limited functionality; parallel findings have been reported previously for other transgene products encoded by AAV vectors [35]. One possible explanation for this apparent paradox may lie in the discovery of significant numbers of SpCas9-specific regulatory T cells (Treg) in the circulation of healthy individuals in addition to effector T cells. Their demonstrated capacity to suppress CTL activity [18••] suggests that the precarious balance between these cell types might determine the success or otherwise of genome editing in vivo, while providing a possible strategy for modulating the impact of pre-existing immunity to Cas9 in the future.

Toward Potential Solutions for Pre-Existing Immunity

Structural Modification of Cas9

One possible solution to the problem of pre-existing immunity is the ‘humanization’ of Cas9 by replacing portions of the bacterial protein with those of human origin in a manner similar to that routinely achieved for other biologicals such as monoclonal antibodies. Unfortunately, Cas9 has no human ortholog which significantly complicates this approach. In addition, it is widely recognised that humanised proteins may still retain some level of immunogenicity and may not, therefore, fully evade immune surveillance [36]. Another potential solution is ‘epitope masking’, which consists of identifying potentially immunogenic peptide sequences and modifying or removing them to prevent detection by the immune system while still maintaining the therapeutic function of the original protein [37]. This has been successful for B cell epitopes for the AAV vector [38,39,40,41] and has been achieved in mice for the Cas9 protein [20]. Nevertheless, there are inevitably limitations to this approach. Targeting immunodominant epitopes has the potential to reduce their immunogenicity in some cases [42] but increase immunogenicity in others [43]. Furthermore, while protein function has been preserved for certain proteins that have undergone epitope masking, such as GFP, Pseudomonas exotoxin A [44] and β-lactamase [45, 46], a similar outcome cannot be guaranteed for Cas9.

Another area for investigation is the potential to intervene in the presentation of epitopes of Cas9 through the inhibition of proteasomal degradation in a manner similar to that exploited by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). It has been shown that regularly interspersed alanine within the Gly-Ala repeat domain of EBV nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) inhibits ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation [47,48,49,50,51], restricting the presentation of EBNA1 peptides. The introduction of such domains into the structure of Cas9 might likewise restrict its proteasomal degradation and presentation to CTLs via HLA class I.

Orthologs of Cas9 from Non-Pathogenic Bacteria

Another potential solution to the issue of immunogenicity may lie in the identification of orthologs of Cas9 from distantly related bacterial species that have no capacity to infect human hosts. Hundreds of CRISPR-Cas9 systems have already been discovered [52] which, in principle, could be tested with the appropriate computer models or phage display for the identification of T and B cell epitopes. Indeed, it may even prove feasible to create a sequential regimen of CRISPR-Cas9 therapies using orthologs with minimal predicted immunogenicity, a new ortholog being selected once immunity to previous variants has become established. Given the enhanced stability of GeoCas9 in human plasma [21•], and that soil, thermal vents and oceanic sediment are the preferred habitat of G. stearothermophilus from which this particular ortholog is derived, prior exposure to the nuclease by potential recipients of genome editing would appear highly unlikely. Although, in practice, GeoCas9 may well prove as immunogenic as either SpCas9 or SaCas9, and is likely, therefore, to elicit primary immune responses in vivo, being non-permissive for human infection removes the spectre of pre-existing antibodies or antigen-specific T cells, facilitating at least one administration of RNP complexes prior to the establishment of entrenched immunity. In this context, the judicious use of immune suppression might prove beneficial, an approach which is less likely to yield benefits when delivering Cas9 into individuals already harbouring memory T and B cells and high titres of neutralising antibodies.

Immune Privilege

The principles of immune privilege might also be exploited in the service of genome editing by providing a microenvironment actively accommodating of foreign proteins such as Cas9. As the initial site to which food antigens and microbial proteins from the gut microbiota are transported, the liver constitutes an environment that is relatively immunosuppressive and is frequently the target organ of choice for delivery of viral vectors carrying transgenes, including Cas9. Importantly, presentation of antigen by liver sinusoidal endothelial cells has been shown to induce CD8+ T cell tolerance [53]: indeed, CD8+ T cells in the liver may demonstrate a reduced life span and are unable to mediate hepatocellular injury due to the loss of cytotoxic function [54]. Given that cytotoxic T cell activity is likely to be the most detrimental facet of adaptive immunity for genetically modified cells transiently expressing Cas9, the unique environment afforded by the liver has contributed significantly to the success of genome editing in vivo.

By virtue of the blood–brain barrier, the brain is also considered a powerfully immune-privileged environment and has, therefore, served as a convenient anatomical site in mice for the delivery of AAV vectors carrying a CRISPR-Cas9 cargo [55]. Furthermore, Staahl and colleagues injected a variant of Cas9 RNP engineered to express multiple SV40 nuclear localization sequences directly into the hippocampus, striatum and cortex of the brains of mice. Importantly, this route of administration failed to induce innate microglial responses, as evidenced by the lack of IBA-1 expression and failure to upregulate a panel of immunologically relevant genes as assessed by qPCR [56••], implying that Cas9 had been smuggled into the brains of mice without registering on the immunological radar. While there is little doubt that such a strategy fails to offer a general solution to the issue of immunogenicity, it may, nevertheless, provide an approach to the treatment of various diseases of neurological origin.

Induction of Immunological Tolerance

While most therapeutic interventions seek merely to reduce immunogenicity, the induction of immunological tolerance to the Cas9 protein might, in principle, provide a permanent solution to the issues of immunity, facilitating in vivo genome editing, unencumbered by adverse immune responses. Prospects for establishing a state of operational tolerance have recently received support from Wagner and colleagues who showed that, in addition to effector T cell responses to SpCas9 in 96% of healthy individuals, antigen-specific Treg cells were also evident in the peripheral circulation and comprised between 11.0 and 71.2% of the total CD4+ T cell response to SpCas9. Importantly, this source of Treg cells displayed the ability to suppress the proliferative response of Cas9-specific effector T cells but not those specific for unrelated antigens derived from cytomegalovirus (CMV). Furthermore, they decreased CTL lysis of target cells expressing Cas9, albeit with only moderate efficacy [18••]. Given the prevalence of Treg cells within the circulation of individuals due to repeated prior exposure to S. pyogenes, strategies for the induction of tolerance that amplify this natural resource might provide a potential way forward.

One such approach involves the purification of autologous Treg cells from the peripheral blood of patients and their re-administration following ex vivo expansion, thereby enhancing the numbers of Treg cells relative to their effector counterparts. Such a strategy has already proven successful for the treatment of inflammatory responses during the early stages of allograft rejection in kidney transplant patients [57]. In this study, Treg cells were polyclonal and non-specific: the expansion of SpCas9-specific Treg cells ex vivo from the recipients of gene therapy might, therefore, be anticipated to demonstrate far greater capacity for tolerance induction, the numbers of Treg cells that can be obtained having the potential to control even pre-existing immunity to Cas9. The preferential use of Cas9 orthologs from distantly related species of bacteria that fail to infect humans may circumvent the issues of entrenched immunity but would doubtless provoke primary immune responses without some form of immune intervention. In this context, the differentiation of dendritic cells from peripheral blood monocytes under conditions known to confer a tolerogenic phenotype might permit the presentation of SpCas9 epitopes to naïve T cells in advance of genome editing, resulting in their polarisation towards a Treg phenotype and participation in the induction of antigen-specific tolerance [58, 59].

Conclusion

There is little doubt that exploiting the unique functionality of CRISPR-Cas9 offers unrivalled opportunities for genome editing in vivo, raising prospects for the treatment of numerous intractable disease states. Nevertheless, the recent demonstration that routine prior exposure to the microorganisms from which Cas9 is commonly derived is responsible for pre-existing immunity to the enzyme poses a significant threat to its use for downstream clinical applications. Clinical trials to date have focussed on the use of CRISPR-Cas9 to modify cells of the immune system ex vivo prior to their re-administration [7], thereby minimising the impact that circulating Cas9-specific T cells and antibodies might have on efficacy. The recent demonstration of genome editing of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from patients with recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa so as to correct causative mutations in the COL7A1 gene [60•] suggests that an ex vivo approach might be extended to the generation of numerous cell types by combining genome editing with induced pluripotency. Nevertheless, the delivery of Cas9 direct to defective cell types in vivo would doubtless constitute a more effective option for many congenital diseases. Such ambitions will, however, necessitate the development of approaches to limiting the impact of pre-existing immunity, for which an attractive strategy might be the expansion of Cas9-specific Treg cells, already prevalent within the circulation of individuals pre-exposed to common human pathogens.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Travis J. Making the cut: CRISPR-genome editing technology shows its power. Science. 2015;350:1456–7.

Wang D, Mou H, Li S, Li Y, Hough S, Tran K, et al. Adenovirus-mediated somatic genome editing of Pten by CRISPR/Cas9 in mouse liver in spite of Cas9 specific immune responses. Hum Gene Ther. 2015;26:432–42.

Wang F, Qi LS. Applications of CRISPR genome engineering in cell biology. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:875–88.

Yin H, Wen X, Chen S, Bogorad RL, Benedetti E, Grompe M, et al. Genome editing with Cas9 in adult mice corrects a disease mutation and phenotype. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:551–3.

• Fogarty NME, McCarthy A, Snijders KE, Powell BE, Kubikova N, Blakeley P, et al. Genome editing reveals a role for OCT4 in human embryogenesis. Nature. 2017;550:67–73. A groundbreaking study which constitutes the first application of genome editing to human embryos, revealing an important role for the pluripotency gene OCT4 in embryogenesis.

Cyranoski D, Ledford H. International outcry over genome-edited baby claim. Nature. 2018;563:607–8.

Normile D. China sprints ahead in CRISPR therapy race. Science. 2017;358:20–1.

Yang Y, Wang Q, Li Q, Men K, He Z, Deng H, et al. Recent advances in therapeutic genome editing in China. Hum Gene Ther. 2018;29:136–45.

Komor AC, Badran AH, Liu DR. CRISPR-based technologies for the manipulation of eukaryotic genomes. Cell. 2017;168:20–36.

Mali P, Esvelt KM, Church GM. Cas9 as a versatile tool for engineering biology. Nat Methods. 2013;10:957–63.

Wright AV, Nunez JK, Doudna JA. Biology and applications of CRISPR systems: harnessing nature’s toolbox for genome engineering. Cell. 2016;164:29–44.

Fellmann C, Gowen BG, Lin PC, Doudna JA, Corn JE. Cornerstones of CRISPR-Cas in drug discovery and therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:89–100.

Sander JD, Joung JK. CRISPR-Cas systems for editing, regulating and targeting genomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:347–55.

Dominguez AA, Lim WA, Qi LS. Beyond editing: repurposing CRISPR-Cas9 for precision genome regulation and interrogation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17:5–15.

Kim H, Kim JS. A guide to genome engineering with programmable nucleases. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15:321–34.

Doudna JA, Charpentier E. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 2014;346:1258096-1–9.

Maggio I, Goncalves MA. Genome editing at the crossroads of delivery, specificity, and fidelity. Trends Biotechnol. 2015;33:280–91.

•• Wagner DL, Amini L, Wendering DJ, Burkhardt L-M, Akyuz L, Reinke P. et al. High prevalence of Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9-reactive T cells within the adult human population. Nat Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0204-6. A comprehensive analysis of pre-existing T cell responses to SpCas9 which reveals the presence not only of effector T cells but also of antigen-specific Treg cells which might be expanded for the induction of immunological tolerance.

Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:520–32.

Chew WL, Tabebordbar M, Cheng JK, Mali P, Wu EY, Ng AH, et al. A multifunctional AAV-CRISPR-Cas9 and its host response. Nat Methods. 2016;13:868–74.

• Harrington LB, Paez-Espino D, Staahl BT, Chen JS, Ma E, Kyrpides NC, et al. A thermostable Cas9 with increased lifetime in human plasma. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1424. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01408-4 Characterisation of Cas9 from G. stearothermophilus demonstrating a broader temperature tolerance and greater stability in human plasma than conventional orthologs from mesophiles, which may make it more suitable for genome editing in vivo.

Blythe MJ, Flower DR. Benchmarking B cell epitope prediction: underperformance of existing methods. Protein Sci. 2005;14:246–8.

Ponomarenko JV, Bourne PE. Antibody-protein interactions: benchmark datasets and prediction tools evaluation. BMC Struct Biol. 2007;7:64.

Chew WL. Immunity to CRISPR Cas9 and Cas12a therapeutics. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2017;10:e1408. https://doi.org/10.1002/wsbm.1408.

Kringelum JV, Lundegaard C, Lund O, Nielsen M. Reliable B cell epitope predictions: impacts of method development and improved benchmarking. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8:e1002829.

Ponomarenko J, Bui HH, Li W, Fusseder N, Bourne PE, Sette A, et al. ElliPro: a new structure-based tool for the prediction of antibody epitopes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:514.

Charlesworth CT, Deshpande PS, Dever DP, Dejene B, Gomez-Ospina N, Mantri S, et al. Identification of pre-existing adaptive immunity to Cas9 proteins in humans. 2018. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2018/01/05/243345. Accessed 20 Dec 2018.

•• Simhadri VL, McGill J, McMahon S, Wang J, Jiang H, Sauna ZE. Prevalence of pre-existing antibodies to CRISPR-associated nuclease Cas9 in the USA population. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2018;10:105–12. A large-scale study of sera from 200 US donors which identified pre-existing antibodies to both SpCas9 and SaCas9. This study confirms the findings of Charlesworth et al. [27], which have yet to be peer reviewed.

van der Burg SH, Visseren MJ, Brandt RM, Kast WM, Melief CJ. Immunogenicity of peptides bound to MHC class I molecules depends on the MHC-peptide complex stability. J Immunol. 1996;156:3308–14.

Sette A, Vitiello A, Reherman B, Fowler P, Nayersina R, Kast WM, et al. The relationship between class I binding affinity and immunogenicity of potential cytotoxic T cell epitopes. J Immunol. 1994;153:5586–92.

Lazarski CA, Chaves FA, Jenks SA, Wu S, Richards KA, Weaver JM, et al. The kinetic stability of MHC class II: peptide complexes is a key parameter that dictates immunodominance. Immunity. 2005;23:29–40.

Nielsen M, Andreatta M. NetMHCpan-3.0; improved prediction of binding to MHC class I molecules integrating information from multiple receptor and peptide length datasets. Genome Med. 2016;8:33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-016-0288-x.

Rivino L, Tan AT, Chia A, Kumaran EA, Grotenbreg GM, MacAry PA, et al. Defining CD8+ T cell determinants during human viral infection in populations of Asian ethnicity. J Immunol. 2013;191:4010–9.

Amoasii L, Hildyard JCW, Li H, Sanchez-Ortiz E, Mireault A, Caballero D, et al. Gene editing restores dystrophin expression in a canine model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Science. 2018;362:86–91.

Lin S-W, Hensley SE, Tatsis N, Lasaro MO, Ertl HCJ. Recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors induce functionally impaired transgene product-specific CD8+ T cells in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3958–70.

Harding FA, Stickler MM, Razo J, DuBridge RB. The immunogenicity of humanized and fully human antibodies: residual immunogenicity resides in the CDR regions. MAbs. 2010;2:256–65.

Nagata S, Pastan I. Removal of B cell epitopes as a practical approach for reducing the immunogenicity of foreign protein-based therapeutics. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:977–85.

Bartel M, Schaffer D, Buning H. Enhancing the clinical potential of AAV vectors by capsid engineering to evade pre-existing immunity. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:204.

Zinn E, Pacouret S, Khaychuk V, Turunen HT, Carvalho LS, Andres-Mateos E, et al. In silico reconstruction of the viral evolutionary lineage yields a potent gene therapy vector. Cell Rep. 2015;12:1056–68.

Li C, Wu S, Albright B, Hirsch M, Li W, Tseng YS, et al. Development of patient-specific AAV vectors after neutralizing antibody selection for enhanced muscle gene transfer. Mol Ther. 2016;24:53–65.

Maheshri N, Koerber JT, Kaspar BK, Schaffer DV. Directed evolution of adeno-associated virus yields enhanced gene delivery vectors. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:198–204.

Yeung VP, Chang J, Miller J, Barnett C, Stickler M, Harding FA. Elimination of an immunodominant CD4+ T cell epitope in human IFN-beta does not result in an in vivo response directed at the subdominant epitope. J Immunol. 2004;172:6658–65.

Mok H, Lee S, Wright DW, Crowe JE. Enhancement of the CD8+ T cell response to a subdominant epitope of respiratory syncytial virus by deletion of an immunodominant epitope. Vaccine. 2008;26:4775–82.

King C, Garza EN, Mazor R, Linehan JL, Pastan I, Pepper M, et al. Removing T-cell epitopes with computational protein design. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:8577–82.

Salvat RS, Parker AS, Choi Y, Bailey-Kellogg C, Griswold KE. Mapping the pareto optimal design space for a functionally deimmunized biotherapeutic candidate. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11:e1003988.

Salvat RS, Choi Y, Bishop A, Bailey-Kellogg C, Griswold KE. Protein deimmunization via structure-based design enables efficient epitope deletion at high mutational loads. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2015;112:1306–18.

Levitskaya J, Coram M, Levitsky V, Imreh S, Steigerwald-Mullen PM, Klein G, et al. Inhibition of antigen processing by the internal repeat region of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen-1. Nature. 1995;375:685–8.

Levitskaya J, Sharipo A, Leonchiks A, Ciechanover A, Masucci MG. Inhibition of ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent protein degradation by the Gly-Ala repeat domain of the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:12616–21.

Dantuma NP, Heessen S, Lindsten K, Jellne M, Masucci MG. Inhibition of proteasomal degradation by the Gly-Ala repeat of Epstein-Barr virus is influenced by the length of the repeat and the strength of the degradation signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8381–5.

Sharipo A, Imreh M, Leonchiks A, Imreh S, Masucci MG. A minimal glycine-alanine repeat prevents the interaction of ubiquitinated I kappa B alpha with the proteasome: a new mechanism for selective inhibition of proteolysis. Nat Med. 1998;4:939–44.

Ossevoort M, Visser BM, van den Wollenberg DJ, van der Voort EI, Offringa R, Melief CJ, et al. Creation of immune ‘stealth’ genes for gene therapy through fusion with the Gly-Ala repeat of EBNA-1. Gene Ther. 2003;10:2020–8.

Shmakov S, Smargon A, Scott D, Cox D, Pyzocha N, Yan W, et al. Diversity and evolution of class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017;15:169–82.

Limmer A, Ohl J, Kurts C, Ljunggren HG, Reiss Y, Groettrup M, et al. Efficient presentation of exogenous antigen by liver endothelial cells to CD8+ T cells results in antigen-specific T-cell tolerance. Nat Med. 2000;6:1348–54.

Bowen DG, Zen M, Holz L, Davis T, McCaughan GW, Bertolino P. The site of primary T cell activation is a determinant of the balance between intrahepatic tolerance and immunity. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:701–12.

Swiech L, Heidenreich M, Banerjee A, Habib N, Li Y, Trombetta J, et al. In vivo interrogation of gene function in the mammalian brain using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:102–6.

•• Staahl BT, Benekareddy M, Coulon-Bainier C, Banfal AA, Floor SN, Sabo JK, et al. Efficient genome editing in the mouse brain by local delivery of engineered Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:431–4. An elegant study that exploits the immune-privileged environment of the brain to secure genome editing following direct delivery of Cas9 RNP complexes: the absence of an immunological gene expression signature suggests minimal recognition by innate immune cells.

Chandran S, Tang Q, Sarwal M, Laszik ZG, Putman AL, Lee K, et al. Polyclonal regulatory T cell therapy for control of inflammation in kidney transplants. Am J Transplant. 2017;17:2945–54.

Leishman A, Silk KM, Fairchild PJ. Pharmacological manipulation of dendritic cells in the pursuit of transplantation tolerance. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2011;16:372–8.

Horton C, Shanmugarajah K, Fairchild PJ. Harnessing the properties of dendritic cells in the pursuit of immunological tolerance. Biom J. 2017;40:80–93.

• Webber BR, Osborn MJ, McElroy AN, Twaroski K, Lonetree C, DeFeo AP, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-based genetic correction for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. NPJ Regen Med. 2016;1:16014. https://doi.org/10.1038/npjregenmed.2016.14. The authors perform genome editing of patient-derived iPSCs to correct the causative mutation of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. The capacity for differentiation of the gene-corrected cells into cell types such as keratinocytes, mesenchymal and haematopoietic stem cells that might be used for treatment of the disease suggests a paradigm for genome editing in the future that may circumvent pre-existing immunity to Cas9.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs Kumaran Shanmugarajah and Tim Davies for helpful discussions.

Funding

Work on tolerance in the authors’ laboratory is supported by Confidence in Concept awards from the MRC (Grant MC_PC_16056) and the Rosetrees Trust (Grant M638).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Cellular Transplants

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wignakumar, T., Fairchild, P.J. Evasion of Pre-Existing Immunity to Cas9: a Prerequisite for Successful Genome Editing In Vivo?. Curr Transpl Rep 6, 127–133 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40472-019-00237-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40472-019-00237-2