Abstract

Purpose of Review

Our review critically examines research on trends in mental health among US adults following the COVID-19 pandemic’s onset and makes recommendations for research on the topic.

Recent Findings

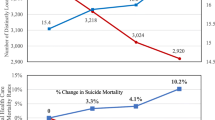

Studies comparing pre-pandemic nationally representative government surveys (“benchmark surveys”) with pandemic-era non-benchmark surveys generally estimated threefold to fourfold increases in the prevalence of adverse mental-health outcomes following the pandemic’s onset. However, studies analyzing trends in repeated waves of a single survey, which may carry a lower risk of bias, generally estimated much smaller increases in adverse outcomes. Likewise in our analysis of benchmark surveys, we estimated < 1% increases in the prevalence of adverse outcomes from 2018/2019–2021. Finally, studies analyzing vital-statistics data estimated spiking fatal-overdose rates, but stable suicide rates.

Summary

Although fatal-overdose rates increased substantially following the pandemic’s onset, evidence suggests the population prevalence of other adverse mental-health outcomes may have departed minimally from prior years’ trends, at least through 2021. Future research on trends through the pandemic’s later stages should prioritize leveraging repeated waves of benchmark surveys to minimize risk of bias.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of Data and Materials

Our R code is Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/twsrj/?view_only=bf350ae7d72948d29c3911588a9e52fc), where readers can find information about accessing the data analyzed.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

McIntosh K. COVID-19: epidemiology, virology, and prevention. 2023 [cited 2023 Apr 12]. Available from: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/covid-19-epidemiology-virology-and-prevention. Accessed 12 Apr 2023.

National Center for Health Statistics. COVID-19 Mortality overview: provisional death counts for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). 2022 [cited 2023 Apr 12]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/mortality-overview.htm. Accessed 12 Apr 2023.

Arias E, Tejada-Vera B, Kochanek KD, Ahmad FB. Provisional life expectancy estimates for 2021. National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.); 2022. Report No.: 23. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr023.pdf. Accessed 12 Apr 2023.

Woolf SH, Masters RK, Aron LY. Effect of the covid-19 pandemic in 2020 on life expectancy across populations in the USA and other high income countries: simulations of provisional mortality data. BMJ. 2021;373: n1343.

Laster Pirtle WN. Racial capitalism: a fundamental cause of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic inequities in the United States. Health Educ Behav. 2020;47:504–8.

Baker MG. Nonrelocatable occupations at increased risk during pandemics: United States, 2018. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:1126–32.

Chen Y-H, Glymour M, Riley A, Balmes J, Duchowny K, Harrison R, et al. Excess mortality associated with the COVID-19 pandemic among Californians 18–65 years of age, by occupational sector and occupation: March through November 2020. Devleesschauwer B, editor. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0252454.

McClure ES, Vasudevan P, Bailey Z, Patel S, Robinson WR. Racial capitalism within public health: how occupational settings drive COVID-19 disparities. Am J Epidemiol. 2020;189:1244–53.

Feldman JM, Bassett MT. Variation in COVID-19 mortality in the US by race and ethnicity and educational attainment. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4: e2135967.

Galea S, Merchant RM, Lurie N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: the need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:817.

Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:547–60.

Martínez-Alés G, Keyes K. Invited commentary: modern epidemiology confronts COVID-19–reflections from psychiatric epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2023;192:856–60.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Unemployment rate rises to record high 14.7 percent in April 2020: The Economics Daily. [cited 2023 Apr 12]. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2020/unemployment-rate-rises-to-record-high-14-point-7-percent-in-april-2020.htm?view_full. Accessed 12 Apr 2023.

Cajner T, Crane L, Decker R, Grigsby J, Hamins-Puertolas A, Hurst E, et al. The U.S. labor market during the beginning of the pandemic recession. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020 May p. w27159. Report No.: w27159. Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w27159.pdf. Accessed 12 Apr 2023.

Bach K. New data shows long Covid is keeping as many as 4 million people out of work. Brookings. 2022 [cited 2023 Apr 12]. Available from: https://www.brookings.edu/research/new-data-shows-long-covid-is-keeping-as-many-as-4-million-people-out-of-work/. Accessed 12 Apr 2023.

Faghri PD, Dobson M, Landsbergis P, Schnall PL. COVID-19 pandemic: what has work got to do with it? J Occup Environ Med. 2021;63:e245–9.

Pandey K, Thurman M, Johnson SD, Acharya A, Johnston M, Klug EA, et al. Mental health issues during and after COVID-19 vaccine era. Brain Res Bull. 2021;176:161–73.

Ernst M, Niederer D, Werner AM, Czaja SJ, Mikton C, Ong AD, et al. Loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Am Psychol. 2022;77:660–77.

Verdery AM, Smith-Greenaway E, Margolis R, Daw J. Tracking the reach of COVID-19 kin loss with a bereavement multiplier applied to the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:17695–701.

Carr D, Boerner K, Moorman S. Bereavement in the time of coronavirus: unprecedented challenges demand novel interventions. J Aging Soc Policy. 2020;32:425–31.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About BRFSS. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system. 2014 [cited 2023 May 30]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/about/index.htm. Accessed 30 May 2023.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About the National Health Interview Survey. 2022 [cited 2023 May 30]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm. Accessed 30 May 2023.

•• Kessler RC, Ruhm CJ, Puac-Polanco V, Hwang IH, Lee S, Petukhova MV, et al. Estimated prevalence of and factors associated with clinically significant anxiety and depression among US adults during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2217223. Study analyzed trends in anxiety/depression by comparing estimates from repeated waves of a single benchmark survey, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

•• Bradley VC, Kuriwaki S, Isakov M, Sejdinovic D, Meng X-L, Flaxman S. Unrepresentative big surveys significantly overestimated US vaccine uptake. Nature. 2021;600:695–700. Study demonstrated potential bias from nonresponse and other design issues in the Household Pulse Survey.

Tolbert J, Ammula M. 10 things to know about the unwinding of the Medicaid continuous enrollment provision. KFF. 2023 [cited 2023 May 23]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/10-things-to-know-about-the-unwinding-of-the-medicaid-continuous-enrollment-provision/. Accessed 30 May 2023.

Sandoval-Olascoaga S, Venkataramani AS, Arcaya MC. Eviction moratoria expiration and COVID-19 infection risk across strata of health and socioeconomic status in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4: e2129041.

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Timeline: understanding the impact of the end of the public health emergency and COVID-19 waivers on SNAP households | Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. 2023 [cited 2023 May 23]. Available from: https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/understanding-the-impact-of-the-end-of-the-public-health-emergency-and. Accessed 30 May 2023.

• Twenge JM, Joiner TE. U.S. Census Bureau‐assessed prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID‐19 pandemic. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37:954–6. Study analyzed trends in anxiety/depression by comparing pre-pandemic estimates from the National Health Interview Survey with pandemic-era estimates from the Household Pulse Survey.

• Twenge JM, McAllister C, Joiner TE. Anxiety and depressive symptoms in U.S. Census Bureau assessments of adults: trends from 2019 to fall 2020 across demographic groups. J Anxiety Disord. 2021;83:102455. Study analyzed trends in anxiety/depression by comparing pre-pandemic estimates from the National Health Interview Survey with pandemic-era estimates from the Household Pulse Survey.

• Panchal N, Kamal R, Cox C, Garfield R. The implications of COVID-19 for mental health and substance use. San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2021. Available from: https://pameladwilson.com/wp-content/uploads/4_5-2021-The-Implications-of-COVID-19-for-Mental-Health-and-Substance-Use-_-KFF-1.pdf. Study analyzed trends in anxiety/depression by comparing pre-pandemic estimates from the National Health Interview Survey with pandemic-era estimates from the Household Pulse Survey. Accessed 30 May 2023.

• Raifman J, Ettman CK, Dean LT, Abdalla SM, Skinner A, Barry CL, et al. Economic precarity, loneliness, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Magalhaes PV da S, editor. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0275973. Study analyzed trends in suicidal ideation by comparing pre-pandemic estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey with pandemic-era estimates from the AmeriSpeak panel.

• Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2019686. Study analyzed trends in depression by comparing pre-pandemic estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey with pandemic-era estimates from the AmeriSpeak panel.

• McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Han H, Barry CL. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US Adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA. 2020;324:93. Study analyzed trends in psychological distress by comparing pre-pandemic estimates from the National Health Interview Survey with pandemic-era estimates from the AmeriSpeak panel.

• Thomeer MB, Moody MD, Yahirun J. Racial and ethnic disparities in mental health and mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Racial Ethnic Health Disparities. 2023;10:961–76. Study analyzed trends in anxiety/depression by comparing pre-pandemic estimates from the National Health Interview Survey with pandemic-era estimates from the Household Pulse Survey.

• Grooms J, Ortega A, Rubalcaba JA-A, Vargas E. Racial and ethnic disparities: essential workers, mental health, and the coronavirus pandemic. Rev Black Polit Econ. 2022;49:363–80. Study analyzed trends in anxiety/depression by comparing pre-pandemic estimates from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System with pandemic-era estimates from the National Panel Study of COVID-19.

• Twenge JM, Joiner TE. Mental distress among U.S. adults during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Clin Psychol. 2020;76:2170–82. Study analyzed trends in psychological distress by comparing pre-pandemic estimates from the National Health Interview Survey with pandemic-era estimates from the Luc.id panel.

Panchal N, Saunders H, Rudowitz R, Cox C. The implications of COVID-19 for mental health and substance use (updated). San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2023. Available from: https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/. Accessed 30 May 2023.

Czeisler MÉ, Lane RI, Petrosky E, Wiley JF, Christensen A, Njai R, et al. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, June 24–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1049–57.

McKnight-Eily LR, Okoro CA, Strine TW, Verlenden J, Hollis ND, Njai R, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence of stress and worry, mental health conditions, and increased substance use among adults during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, April and May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:162–6.

McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Han H, Barry CL. Trends in psychological distress among US adults during different phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5: e2144776.

• Breslau J, Finucane ML, Locker AR, Baird MD, Roth EA, Collins RL. A longitudinal study of psychological distress in the United States before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev Med. 2021;143:106362. Study analyzed trends in distress by comparing estimates from repeated waves of a single non-benchmark sample from the Rand American Life Panel.

• Wanberg CR, Csillag B, Douglass RP, Zhou L, Pollard MS. Socioeconomic status and well-being during COVID-19: a resource-based examination. J Appl Psychol. 2020;105:1382–96. Study analyzed trends in anxiety/depression by comparing estimates from repeated waves of a single non-benchmark sample from the Rand American Life Panel.

• Brenan M. Americans’ Reported Mental Health at New Low; More Seek Help. Gallup.com. 2022 [cited 2023 May 24]. Available from: https://news.gallup.com/poll/467303/americans-reported-mental-health-new-low-seek-help.aspx. Study analyzed trends in poor/fair mental health by comparing estimates from repeated waves of a single non-benchmark Gallup survey. Accessed 24 May 2023.

Fritz CO, Morris PE, Richler JJ. Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2012;141:2–18.

•• Goodwin RD, Dierker LC, Wu M, Galea S, Hoven CW, Weinberger AH. Trends in U.S. depression prevalence from 2015 to 2020: the widening treatment gap. Am J Prev Med. 2022;63:726–33. Study analyzed trends in anxiety/depression by comparing estimates from repeated waves of a single benchmark survey, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

•• Villas-Boas SB, White JS, Kaplan S, Hsia RY. Trends in depression risk before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Renteria E, editor. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0285282. Study analyzed trends in anxiety/depression by comparing estimates from repeated waves of a single benchmark survey, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH): Population Data. Substance Abuse & Mental Health Data Archive. [cited 2023 May 10]. Available from: https://www.datafiles.samhsa.gov/dataset/national-survey-drug-use-and-health-2020-nsduh-2020-ds0001. Accessed 10 May 2023.

Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Hwang IH, Puac-Polanco V, Sampson NA, Ziobrowski HN, et al. Changes in prevalence of mental illness among US adults during compared with before the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2022;45:1–28.

Bohnert ASB, Sen S. Deaths attributed to psychiatric disorders in the United States, 2010–2018. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:1825–7.

Slavova S, Delcher C, Buchanich JM, Bunn TL, Goldberger BA, Costich JF. Methodological complexities in quantifying rates of fatal opioid-related overdose. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2019;6:263–74.

•• Ehlman DC, Yard E, Stone DM, Jones CM, Mack KA. Changes in suicide rates — United States, 2019 and 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:306–12. Study analyzed trends in suicide rates in vital statistics data.

•• Curtin S, Garnett M, Ahmad F. Provisional numbers and rates of suicide by month and demographic characteristics: United States, 2021. National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.); 2022 Sep. Report No.: 24. Available from: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/120830. Accessed 30 May 2023. Study analyzed trends in suicide rates in vital statistics data.

•• Stone DM, Mack KA, Qualters J. Notes from the Field: Recent changes in suicide rates, by race and ethnicity and age group — United States, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:160–2. Study analyzed trends in suicide rates in vital statistics data.

•• Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Spencer MR, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2020. NCHS Data Brief. 2021;1–8. Study analyzed trends in fatal-overdose rates in vital statistics data.

•• Spencer MR, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 2001–2021. NCHS Data Brief. 2022;1–8. Study analyzed trends in fatal-overdose rates in vital statistics data.

•• Friedman JR, Hansen H. Evaluation of increases in drug overdose mortality rates in the US by race and ethnicity before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79:379. Study analyzed trends in fatal-overdose rates in vital statistics data.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. [cited 2023 May 10]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.html. Accessed 10 May 2023.

Blewett LA, Drew JAR, King ML, Williams KC, Del Ponte N, Convey P. IPUMS Health Surveys: National Health Interview Survey, Version 7.2. Minneapolis: IPUMS; 2022. Available from: https://nhis.ipums.org/. Accessed 10 May 2023.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health Interview Survey. [cited 2023 May 10]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/index.htm. Accessed 10 May 2023.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health. [cited 2023 May 10]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health. Accessed 10 May 2023.

IPUMS. 2019 NHIS Redesign. IPUMS Health Surveys. [cited 2023 May 10]. Available from: https://nhis.ipums.org/nhis/userNotes_2019_NHIS_Redesign.shtml. Accessed 10 May 2023.

Daly M, Robinson E. Psychological distress and adaptation to the COVID-19 crisis in the United States. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;136:603–9.

Goodwin RD, Weinberger AH, Kim JH, Wu M, Galea S. Trends in anxiety among adults in the United States, 2008–2018: rapid increases among young adults. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;130:441–6.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Report No.: SMA 16-4984.

Rockhill B. Theorizing about causes at the individual level while estimating effects at the population level: implications for prevention. Epidemiology. 2005;16:124–9.

Peterson S, Toribio N, Farber J, Hornick D. Nonresponse Bias Report for the 2020 Household Pulse Survey. United States Census Bureau; 2021. Available from: https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/demo/technical-documentation/hhp/2020_HPS_NR_Bias_Report-final.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2023.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System: 2021 Summary Data Quality Report. 2022. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2021/pdf/2021-DQR-508.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2023.

National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey: 2021 Survey Description. 2022. Available from: https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2021/srvydesc-508.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2023.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Report No.: PEP22-07-01–005. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt39443/2021NSDUHFFRRev010323.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2023.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). National Center for Health Statistics. 2022 [cited 2023 May 31]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/sources-definitions/nsduh.htm. Accessed 31 May 2023.

NORC at the University of Chicago. Technical Overview of the AmeriSpeak Panel: NORC’s Probability-Based Household Panel. 2022. Available from: https://amerispeak.norc.org/content/dam/amerispeak/research/pdf/AmeriSpeak%20Technical%20Overview%202019%2002%2018.pdf. Accessed 31 May 2023.

Pollard M, Baird M. The RAND American Life Panel: Technical Description. RAND Corporation; 2017 [cited 2023 May 11]. Available from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1651.html. Accessed 11 May 2023.

Kreuter F. What surveys really say. Nature. 2021;600:614–5.

Keiding N, Louis TA. Perils and potentials of self-selected entry to epidemiological studies and surveys. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc. 2016;179:319–76.

Parolin Z, Curran M, Matsudaira J, Waldfogel J, Wimer C. Estimating monthly poverty rates in the United States. J Policy Anal Manage. 2022;41:1177–203.

Wheaton L, Giannarelli L, Dehry I. 2021 Poverty projections: assessing the impact of benefits and stimulus measures. Washington D.C.: Urban Institute; 2021. Available from: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104603/2021-poverty-projections_0_0.pdf. Accessed 11 May 2023.

Ridley M, Rao G, Schilbach F, Patel V. Poverty, depression, and anxiety: causal evidence and mechanisms. Science. 2020;370:eaay0214.

Zhu JM, Myers R, McConnell KJ, Levander X, Lin SC. Trends in outpatient mental health services use before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff. 2022;41:573–80.

McBain RK, Cantor J, Pera MF, Breslau J, Bravata DM, Whaley CM. Mental health service utilization rates among commercially insured adults in the US during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Health Forum. 2023;4: e224936.

Ali AK, Wehby GL. State eviction moratoriums during the COVID-19 pandemic were associated with improved mental health among people who rent. Health Aff. 2022;41:1583–9.

An X, Gabriel SA, Tzur-Ilan N. More than shelter: the effect of rental eviction moratoria on household well-being. AEA Pap Proc. 2022;112:308–12.

Leifheit KM, Pollack CE, Raifman J, Schwartz GL, Koehler RD, Rodriguez Bronico JV, et al. Variation in state-level eviction moratorium protections and mental health among US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4: e2139585.

Dore EC, Livingston MD III, Shafer PR. Easing cash assistance rules during COVID-19 was associated with reduced days of poor physical and mental health. Health Aff. 2022;41:1590–7.

Donnelly R, Farina MP. How do state policies shape experiences of household income shocks and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic? Soc Sci Med. 2021;269: 113557.

Courtin E, Kim S, Song S, Yu W, Muennig P. Can social policies improve health? A systematic review and meta-analysis of 38 randomized trials. Milbank Q. 2020;98:297–371.

Bradley EH, Canavan M, Rogan E, Talbert-Slagle K, Ndumele C, Taylor L, et al. Variation In health outcomes: the role of spending on social services, public health, and health care, 2000–09. Health Aff. 2016;35:760–8.

Dam D, Melcangi D, Pilossoph L, Toner-Rodgers A. What have workers done with the time freed up by commuting less?. New York: Federal Reserve Bank of New York; 2022. Available from: https://libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org/2022/10/what-have-workers-done-with-the-time-freed-up-by-commuting-less/. Accessed 12 May 2023.

Aksoy CG, Barrero JM, Bloom N, Davis S, Dolls, Zarate P. Commute time savings when working from home. Washington D.C.: Center for Economic Policy Research; 2023. Available from: https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/commute-time-savings-when-working-home. Accessed 12 May 2023.

Mayol-Garcia Y. Pandemic brought parents and children closer: more family dinners, more reading to young children. Census.gov. [cited 2023 May 12]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/01/parents-and-children-interacted-more-during-covid-19.html. Accessed 12 May 2023.

Clark B, Chatterjee K, Martin A, Davis A. How commuting affects subjective wellbeing. Transportation. 2020;47:2777–805.

Künn-Nelen A. Does commuting affect health? Health Econ. 2016;25:984–1004.

Artazcoz L, Cortes I, Escriba-Aguir V, Cascant L, Villegas R. Understanding the relationship of long working hours with health status and health-related behaviours. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:521–7.

Sato K, Kuroda S, Owan H. Mental health effects of long work hours, night and weekend work, and short rest periods. Soc Sci Med. 2020;246: 112774.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID Data Tracker. US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC. 2023 [cited 2023 Apr 19]. Available from: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker. Accessed 19 Apr 2023.

Pierce M, McManus S, Jessop C, John A, Hotopf M, Ford T, et al. Says who? The significance of sampling in mental health surveys during COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:567–8.

Hedden S, Gfroerer J, Barker P, Smith S, Pemberton MR, Saavedra LM, et al. Comparison of NSDUH mental health data and methods with other data sources. CBHSQ Data Review. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2012 [cited 2023 May 15]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK390286/. Accessed 15 May 2023.

Funding

J.E.G.’s and R.P.’s research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health (T32MH013043). J.E.G.’s research was additionally supported by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U48DP006396). J.R.P.’s research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health (K01DA058085).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.E.G. reviewed and interpreted the literature, conducted the statistical analyses, and drafted the initial version of the manuscript. All other authors advised J.E.G. on the literature review and statistical analyses and provided feedback on subsequent drafts of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

We used publicly available, deidentified data and thus were exempt from IRB review.

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Eisenberg-Guyot, J., Presskreischer, R. & Pamplin, J.R. Psychiatric Epidemiology During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Curr Epidemiol Rep (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-024-00342-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-024-00342-6