Abstract

Brittle basement and sedimentary rocks, in particular if these are underlain by radiogenic crust, are considered a prime target for enhanced geothermal systems (EGS). They are marked by high geothermal gradients, caused by radiogenic heat production, and are well suited to be used for geothermal doublets after hydraulic stimulation. Critical conditions for successful EGS projects are: (a) tectonic stresses close to failure, allowing creation of induced fractures by means of hydraulic stimulation; (b) sufficient high temperatures >150 °C, preferably in excess of 200 °C, at depths of less than 5 km; (c) sufficient high water flow rates, to be sustained through induced fractures. For geothermal production, knowledge on thermo-mechanical properties of the lithosphere provides critical constraints on crustal stresses and basement temperatures. We developed a freely available 1D thermal and rheological model for basement-sedimentary areas. This tool helps to understand variability of deep temperatures, as an effect of uncertainties in thermal and rheological properties and tectonic constraints for the lithosphere, important for assessing geothermal prospectivity. The tool is demonstrated on the Central System in Spain and the adjacent Tajo and Duero basins.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Economics limit development of enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) to areas with elevated geothermal gradients. Sufficient high temperatures (>150 °C, preferably in excess of 200 °C) are required at depths of less than 5 km, partly due to increasing drilling costs (e.g. Limberger et al. 2014), but mainly due to decreasing chances at large depths to induce fractures with hydraulic stimulation allowing sufficient and sustainable water flow rates. An example of such a favourable setting is an area where highly radiogenic crust is insulated by overlying brittle basement and sedimentary rocks (e.g. Cloetingh et al. 2010), well suited for geothermal doublets after hydraulic stimulation (e.g. Wassing et al. 2014).

In basement-sedimentary environments, explored for EGS prospectivity, the target depth is generally beyond the reach of existing oil and gas wells (e.g. Bonté et al. 2012). Thermo-mechanical characterization of such a setting typically lacks calibration data at relevant depth. The characterization depends on tectonic forward models, with boundary conditions such as surface or basement heat flow (e.g. Van Wees et al. 2009; Cloetingh et al. 2010), and thermal and rheological properties typically based on simplistic stratified models with constant properties per layer (e.g. Van Wees and Beekman 2000; Cloetingh et al. 2010). In the last years, basin modelling studies have made significant advances improving parametrization of thermal properties (e.g. Hantschel and Kauerauf 2009). For the lithosphere, recent studies highlight the importance of variability of thermal and rheological properties as a function of lithotype, temperature and pressure (e.g. Tesauro et al. 2009).

In order to facilitate geothermal exploration, we developed a freely available spreadsheet tool with tectonically-constrained thermal and rheological predictions based on up-to-date parametrization. In this paper, we highlight its features in view of advancing and simplifying the construction of thermal and rheological strength profiles and to assess sensitivity of results to different interpretation scenarios. The tool is demonstrated on a case study for the Spanish Central System and the adjacent Tajo and Duero basins. Here, we investigate scenarios for radiogenic heat production in basement rocks, with or without sedimentary cover, potentially suited for the development of enhanced geothermal systems.

2 Method

For the construction of 1D temperature and rheology we adopt a steady-state conductive thermal model, solved for temperature boundary conditions at the surface and a lithospheric thickness, denoted as Lithosphere Asthenosphere Boundary (LAB), at which the temperature corresponds to 1300 °C.

For the calculation of temperature, the depth range of the lithosphere is subdivided in depth intervals in order of 100 m. For each depth interval, adopting constant heat flow Q at the top of the interval z = z 0 and constant thermal conductivity k and radiogenic heat production A in this interval, the temperature in the interval can be obtained by:

Based on a default geotherm and hydrostatic pressure, the temperature- and pressure-dependent thermal properties are estimated for all intervals (see Table 1 and sections below), and subsequently used to estimate surface heat flow to match the LAB depth (cf. Van Wees et al. 2009). Before the temperature is computed, the heat flow is extrapolated downwards to obtain the heat flow as a function of depth, \( Q\left( z \right) \) (W m−2) at the top of all intervals, by subtracting the integral of the radiogenic heat production between the surface and depth \( z \), \( \mathop \smallint \limits_{0}^{z} A\left( \zeta \right)d\zeta \) (W m−2), from the surface heat flow:

Since the updated properties are not entirely consistent with the default geothermal gradient and associated thermal properties, several iterations are required to ensure that the surface heat flow honours the lower boundary condition in agreement with the LAB temperature at a specified depth.

2.1 Thermal conductivity

In many cases, properties of sediments and crustal basement have not been measured, or have been measured at pressures and temperatures not representative for the in situ conditions of the rock. In this chapter, we outline various approaches to constrain thermal and mechanical properties of rocks, including thermal conductivity, radiogenic heat production, porosity and permeability, and rheological parameters.

Throughout the whole model the thermal conductivity is temperature and pressure dependent (Fig. 1), resulting in a collection of 1D thermal conductivity profiles:

where \( k_{SED} \left( z \right) \), \( k_{UC} \left( z \right) \), \( k_{LC} \left( z \right) \) and \( k_{LM} \left( z \right) \) are thermal conductivities (W m−1 K−1) as a function of depth \( z \) (m) for the sediments, upper crust, lower crust and lithospheric mantle, respectively. \( z_{topUC} \), \( z_{topLC} \), \( z_{topLM} \) and \( z_{LAB} \) are the depths (m) of the top of the upper crust, lower crust, lithospheric mantle and the lithosphere-asthenosphere boundary, respectively. For the different lithotypes in the sedimentary layer we use the relationship defined by Sekiguchi (1984) for the thermal correction of the matrix thermal conductivity:

where \( \lambda_{i}^{20} \) is the matrix thermal conductivity at room temperature (20 C°) (W m−1 K−1) and \( T \) is the temperature (K). The temperature-dependent matrix thermal conductivity for each lithological component and the temperature-dependent thermal conductivity of the pore fluid are calculated separately. Matrix conductivities of shale and carbonates are also corrected for the change in anisotropy with increasing compaction (cf. Hantschel and Kauerauf 2009).

Fixed densities are assumed for all layers to calculate the vertical effective stress. For the pore fluid, we assume pure water and we adopt hydrostatic conditions. The effective vertical stress \( \sigma_{v}^{'} \) (MPa) is obtained by subtracting the hydrostatic pressure from the lithostatic stress. Then the function of \( \sigma_{v}^{'} \) with depth \( z \) (m) is used for calculating compaction curves.

For each lithotype we adopt the depositional porosity defined by Hantschel and Kauerauf (2009) as surface porosity. These surface porosities are then combined with corresponding compaction coefficients to calculate the porosity at each depth.

The harmonic mean is taken from the different matrix thermal conductivities to obtain the bulk rock matrix conductivity \( k_{bulkmatrix} \) (W m−1 K−1) (Eq. 5). The harmonic mean was chosen over the geometric mean because it is better suited for horizontal layered systems such as the infill of sedimentary basins, which we try to encompass in our single sedimentary layer. Finally, the bulk thermal conductivity of the sedimentary layer \( k_{sed} \) (W m−1 K−1) is obtained by using the geometric mean of the bulk rock matrix thermal conductivity and the pore fluid \( k_{w} \) (W m−1 K−1):

where \( \phi \) is the porosity (0–1) and \( n \) is the number of lithological components for the matrix thermal conductivity.

For the deeper layers, we assume that the effective vertical stress is equal to the lithostatic pressure to correct for the pressure dependency of the thermal conductivity (Eq. 4–6).

For the upper and lower crust, we use the temperature- and pressure-dependent relations described by Chapman (1986) that are based on thermal conductivity measurements:

where \( \lambda_{i}^{0} \) is the thermal conductivity (W m−1 K−1) at a temperature of 0 °C and at atmospheric pressure, \( b \) (K−1) and \( c \) (km−1) are constants, \( \sigma_{v}^{'} \) is the effective vertical stress and \( T \) is the temperature (°C). With increasing temperature, the contribution of the radiative component of the thermal conductivity increases compared to the lattice component (e.g. Hofmeister 1999). This effect is especially relevant for lithospheric mantle that consists mainly of olivine. We use Schatz and Simmons (1972) for the temperature-dependent radiative contribution \( \lambda_{rad} \left( T \right) \) and follow Xu et al. (2004) for the temperature- and pressure-dependent lattice thermal conductivity \( \lambda_{lat}^{25} \left( {T,\sigma_{v}^{'} } \right) \):

where \( \lambda_{i}^{25} \) is the thermal conductivity (W m−1 K−1) of olivine at a temperature of 25 °C and at atmospheric pressure, \( T \) is the temperature (K) and \( \sigma_{v}^{'} \) is the effective lithostatic stress (GPa) (Fig. 1).

Temperature and porosity dependency of bulk thermal conductivity for a typical shale (SH red) and sandstone (SS orange) sequence of 6 km thick, underlain by crystalline basement. The thermal conductivity of the sediments (center) consists of a mixture between the thermal conductivity of the pore fluid (blue) and rock matrix (striped/dotted). The ratio between pore fluid and matrix is determined by the porosity of the rock (left) that generally decreases with depth due to overburden compaction. Thermal conductivity of the pore fluid (blue) and rock matrix are also dependent on the geothermal gradient (right), leading to increasing thermal conductivities with increasing temperature (center). (Color figure online)

2.2 Radiogenic heat generation and partition model

Fixed values for the radiogenic heat generation \( A\left( z \right) \) (μW m−3) are used throughout the lithosphere:

where \( A_{SED} \), \( A_{UC} \),\( A_{LC} \) and \( A_{LM} \) are the values of radiogenic heat generation (μW m−3) used for sediments, upper crust, lower crust and lithospheric mantle, respectively. For the sedimentary layer, fixed values for the radiogenic heat generation \( A_{bulk } \) are used depending on the lithotype. For most continental lithosphere, the ratio between the surface heat flow \( Q_{0} \) (W m−2) and the radiogenic heat generation in the upper crust \( A_{UC} \) abides the partition model of Pollack and Chapman (1977) (Eq. 9), where \( r \) is a ratio (0–1) and \( D_{UC} \) is the thickness of the upper crust (m). The ratio \( r \) in the partition model usually lies between 0.26 and 0.4 (e.g. Pollack and Chapman 1977; Hasterok and Chapman 2011) for continental crust.

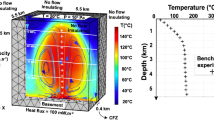

Figure 2 shows an example of a thermal model with a lithosphere thickness of 110 km, and a Moho depth at 36 km. A 6-km sequence of sediments is underlain by a radiogenic upper crust of 15 km, marked by r = 0.4, and a lower crust of 15 km. The model parametrization and corresponding temperatures demonstrate a strong sensitivity to the lithological composition of sediment infill.

In summary, thermal properties are strongly dependent on lithotype and are marked by a significant variation as a function of porosity pressure and temperature.

2.3 Rheology construction

Deformation distribution is determined by the interplay of intraplate forces and the rheological structure of the lithosphere (e.g. Ziegler et al. 1995, 1998). Therefore, rheological parametrization is an important issue to be considered in models for stress prediction in general, and in geothermal exploration contexts where reservoir permeability is often controlled by faults and fractures (e.g. Cloetingh et al. 2010).

For rheology, it is assumed that Earth’s lithosphere can behave either brittle, or ductile, depending on which deformation mechanism requires least differential stress, given the tectonic setting (extension, strike-slip, or compression).

The differential stress required for ductile deformation depends on composition, temperature, presence or absence of fluids, and sustained strain rates. These are constrained by power-law and Dorn-law creep formula, determined from lab experiments (e.g. Carter and Tsenn 1987; Kirby and Kronenberg 1987; Tesauro et al. 2010). Typically, the differential stress is valid for a specific strain rate and decreases exponentially with increasing temperature and depth.

The differential stress required for brittle deformation is largely independent on temperature and composition of the rock, but increases from zero linearly with depth (Byerlee 1978). Consequently, rocks easily break and slide at shallow depth, while at larger depth and at increasing temperature, ductile deformation becomes the dominant deformation mechanism.

Theoretical rheological models (e.g. Panza et al. 1980; Kusznir and Park 1987; Stephenson and Cloetingh 1991; Van Wees and Beekman 2000; Cloetingh and Van Wees 2005) indicate that thermally stabilized continental lithosphere consists of mechanically strong upper crust, separated by weak lower crust from the strong upper part of the lithospheric mantle, which in turn overlies the weak lower lithospheric mantle. The strength of continental crust depends largely on its composition, thermal regime and presence of fluids, and also on the availability of pre-existing crustal discontinuities. Rheological types in our model can be chosen from the lithotypes defined by Tesauro et al. (2009).

Figure 3 shows an example of rheological strength profiles for two extreme cases (pure sandstone and pure shale) of sediment infill (cf. Figure 2). It demonstrates the strong dependency of the mechanical structure on temperature, which in turn is controlled by thermal properties of sediments.

Geothermal gradients (left) and strength profiles (right), for the same shale- (red) and sandstone-dominated (orange) example (Fig. 2). A dry quartzite is adopted for the upper crust, mafic granulite for the lower crust, and dry olivine for the mantle. Negative values indicate a compressional stress regime, while positive values indicate extension. (Color figure online)

a Active (far-field) tectonic stresses around the Iberia Microplate from moment tensor focal mechanisms: extension (blue), strike-slip (white), and compression (red) (after De Vicente et al. 2008). b Relationship between seismicity and main Cenozoic faults of western Iberia. c Subsiding (−) and uplifting (+) zones in the Iberia foreland related to active stresses. The Central system (CS) is related to the central WSW-ENE fault system. (Color figure online)

3 Application to the Central System in Iberia

The modelling approach is demonstrated for the Central System (CS) in Iberia and two adjacent basins: the Duero Basin (DB) to the north and the Tajo Basin (TB) to the south. The Central System mountain range is located in the center of Spain (Fig. 5). The Iberian Peninsula is a tectonically active region, generally marked by a strike-slip regime with NW–SE compression (De Vicente et al. 2011). In particular, neotectonic studies and seismicity patterns show that the WSW-ENE trending Central System is marked by a perpendicular NNW-SSE maximum horizontal stress (Fig. 4). Induced shear fractures are likely to partly follow natural weak zones, trending in directions that can favour movements with a dominant strike-slip and/or reverse component, depending on their orientation (De Vicente et al. 2008, 2011). It may also be possible that portions of existing strike-slip (and to a lesser extent thrust faults) provide natural conduits for hot water, when drilled.

Heat flow measurements in most of Iberia are scarce (Fig. 5). They suggest average values in the order of 60–70 mW m−2 in Western Iberia, and higher values to the east, including the Catalan Coastal Ranges. Despite relatively low heat flows over most of Iberia, spatial variability related to crustal heterogeneity—i.e. granitic heat production or natural heat convection—can be very high. Lithosphere models calibrated by estimates on lithospheric thickness and thermal properties of the lithosphere layers, including crust and sediments (e.g. Cloetingh et al. 2005; Tejero and Ruiz 2002), allow quantitative assessments of temperature variability in relation to variations in thermal properties, useful for exploration and development of enhanced geothermal systems (Cloetingh et al. 2010).

3.1 Thermal results

We applied our 1D thermal and rheological construction on Iberia for the Central System and the adjacent Neogene basins, the Duero Basin to the north and Tagus Basin to the south (Fig. 6). The crustal geometry, lithosphere thickness and sediment infill have been based on earlier studies including Tejero and Ruiz (2002), De Vicente et al. (2007) and Torne et al. (2015). Model parameters have been listed in Table 1 and model scenarios in Table 2. In the default model, it is assumed that the upper crust of the Central System is marked by higher heat production than the basement underlying the Duero and Tagus basins, due to the presence of local granitic bodies, extending over the whole crust (e.g. De Vicente et al. 2007). Consequently, the basement temperatures in the CS are significantly elevated compared to the adjacent basins. In addition, the model shows that thermal properties of sediments can greatly influence the regional heat flow of a basin: thermal blanketing by sediments with lower conductivity than the underlying basement enhances geothermal gradients in the Duero and Tagus basins. Thermal blanketing of highly radiogenic granitic bodies by low-conductive sediments could lead to the largest enhancement of geothermal gradients, which is very likely in the western Tagus Basin (De Vicente et al. 2007). While we assume steady-state conditions for our models, erosion of 1–2 km in the last 5 My (De Vicente et al. 2008) is likely to have induced a ca. 10% increase in rock temperatures, as a result of heat advection, relative to steady-state values (e.g. Cloetingh et al. 2010).

Modelled geothermal gradients for the Central System (CS black), the Duero Basin (DB yellow), and the Tajo Basin (TB red), representative for the locations in the cross section given in Fig. 6. Thermal properties of sediments, upper crust, lower crust, and lithospheric mantle are given in Table 2. The Central System is modelled with normal (CS black striped) and high (CS black) values for radioactive heat production in the upper crust. For the Duero Basin, a typical sandstone lithology (SS) was chosen (DB yellow), while the Tajo Basin is tested for both a typical sandstone lithology (SS) with normal radiogenic heat production in the upper crust (TB red striped) and a clay-rich sandstone (SSCR) in combination with high radioactive heat production in the upper crust (TB red). (Color figure online)

3.2 Implications on rheology

Rheological reconstructions indicate that the lithosphere is relatively weak in the area of the Central System compared to its margins, due to elevated temperatures and a relative thick crust (Tejero and Ruiz 2002; Fig. 8). Many findings are in accordance with a weak shear resistance in the area of the Central System. Van Wees et al. (1996) show that flexural rigidity of the CS and adjacent basins is in the order of few kilometers. Analogue and numerical models strongly suggest a weak zone in the area of the Central System, resulting in short wave-length deformation super-imposed on long wave-length buckling for the western part of Iberia (Fernández-Lozano et al. 2012).

The inferred concentration of brittle deformation within upper portions of the crust in this area, appears to be consistent with data from structural mapping, showing active thrusting and strike-slip deformation (De Vicente et al. 2007, 2008). The active faults and fractures in basement rocks are likely to provide natural conduits for flow and may cause elevated temperatures, in excess of the steady-state geotherm due to natural convection (e.g. Lipsey et al. 2016).

4 Conclusions

Thermal and rheological models, constrained by tectonic concepts and geophysical constraints help to assess the geothermal prospectivity of basement-sedimentary areas. They enable deep thermo-mechanical characterization, as a function of uncertainties in thermal and rheological properties and tectonic constraints on the deep lithosphere structure. To assist geothermal exploration, we developed an easy-to-use spreadsheet allowing calculations of 1D steady-state geotherms and rheological strength profiles. The public domain tool is available from the www.thermogis.nl and incorporates lithotype, pressure- and temperature-dependent thermal and rheological properties. The tool has been demonstrated on the Central System in Spain, which is a potential target for EGS development. Results of the model show that the thermal gradient in the top 5 km is strongly influenced by the thermal properties of sediments, and underlying radiogenic crust, suggesting elevated thermal gradients in the Central System. These results, together with detailed maps of existing thrust/strike-slip faults and constraints on crustal stress fields, can be used to target natural conduit zones of hot fluids. Despite relatively low heat flows over most of Iberia, spatial variability related to crustal heterogeneity –i.e. granitic heat production or natural heat convection—can be very high. This makes Iberia a region of interest for EGS.

References

Bonté D, Van Wees JD, Verweij JM (2012) Subsurface temperature of the onshore Netherlands: new temperature dataset and modelling. Geol Mijnbouw 91:491–515

Byerlee JD (1978) Fiction of rocks. Pure Appl Geophys 116:615–626

Carter NL, Tsenn MC (1987) Flow properties of continental lithosphere. Tectonophysics 136:27–63

Chapman DS (1986) Thermal gradients in the continental crust. Geol Soc Lond Spec Publ 24:63–70

Cloetingh S, Van Wees J-D (2005) Strength reversal in Europe’s intraplate lithosphere: transition from basin inversion to lithospheric folding. Geology 33:285–288

Cloetingh S, Ziegler PA, Beekman F, Andriessen PAM, Hardebol N, Dèzes P (2005) Intraplate deformation and 3D rheological structure of the Rhine Rift System and adjacent areas of the northern Alpine foreland. Int J Earth Sci 94:758–778

Cloetingh S, Van Wees JD, Ziegler PA, Lenkey L, Beekman F, Tesauro M, Förster A, Norden B, Kaban M, Hardebol N, Genter A, Guillou-Frottier L, Ter Voorde M, Sokoutis D, Willingshofer E, Cornu T, Worum G, Bonté D (2010) Lithosphere tectonics and thermo-mechanical properties: an integrated modelling approach for enhanced geothermal systems exploration in Europe. Earth Sci Rev 102:159–206

De Vicente G, Vegas R, Muñoz Martín A, Silva PG, Andriessen P, Cloetingh S, González Casado JM, van Wees JD, Álvarez J, Carbó A, Olaiz A (2007) Cenozoic thick-skinned deformation and topography evolution of the Spanish Central System. Global Planet Change 58:335–381. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2006.11.042

De Vicente G, Cloetingh S, Muñoz Martín A, Olaiz A, Stich D, Vegas R, Galindo-Zaldívar J, Fernández-Lozano J (2008) Inversion of moment tensor focal mechanisms for active stresses around the microcontinent Iberia: tectonic implications. Tectonics 27:1–2. doi:10.1029/2006TC002093

De Vicente G, Cloetingh S, van Wees JD, Cunha PP (2011) Tectonic classification of Cenozoic Iberian foreland basins. Tectonophysics 502:38–61. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2011.02.007

Fernández M, Marzám I, Correia Ramalho E (1998) Heat flow, heat production, and lithospheric thermal regime in the Iberian Peninsula. Tectonophysics 291:29–53

Fernández-Lozano J, Sokoutis D, Willingshofer E, Dombrádi E, Martín AM, De Vicente G, Cloetingh S (2012) Integrated gravity and topography analysis in analog models: intraplate deformation in Iberia. Tectonics 31:TC6005. doi:10.1029/2012TC003122

Hantschel T, Kauerauf A (2009) Fundamentals of basin and petroleum systems modeling. Springer, Berlin. ISBN 978-3540723172

Hasterok D, Chapman DS (2011) Heat production and geotherms for the continental lithosphere. Earth Planet Sci Lett 307:59–70

Hofmeister AM (1999) Mantle values of thermal conductivity and the geotherm from phonon lifetimes. Science 283:1699–1702

Kirby SH, Kronenberg AK (1987) Rheology of the lithosphere: selected topics. Rev Geophys Space Phys 25:1219–1244

Kusznir NJ, Park RG (1987) The extensional strength of the continental lithosphere; its dependence on geothermal gradient, and crustal composition and thickness. Geol Soc Lond Spec Publ 28:35–52

Limberger J, Calcagno P, Manzella A, Trumpy E, Boxem T, Pluymaekers M, van Wees JD (2014) Assessing the prospective resource base for enhanced geothermal systems in Europe. Geotherm Energy Sci 2:55–71

Lipsey L, Pluymaekers M, Goldberg T, Van Oversteeg K, Ghazaryan L, Cloetingh S, Van Wees JD (2016) Numerical modelling of thermal convection in the Luttelgeest carbonate platform, the Netherlands. Geothermics. doi:10.1016/j.geothermics.2016.05.002

Panza CF, Mueller S, Calganile G (1980) The gross features of the lithosphere-asthenosphere system in Europe from seismic surface waves and body waves. Pure appl Geophys 118:1209–1213

Pollack HN, Chapman DS (1977) On the regional variation of heat flow, geotherms, and lithospheric thickness. Tectonophysics 38:279–296

Schatz JF, Simmons G (1972) Thermal conductivity of Earth materials at high temperatures. J Geophys Res. doi:10.1029/JB077i035p06966

Sekiguchi K (1984) A method for determining terrestrial heat flow in oil basinal areas. Tectonophysics 103:67–79

Stephenson RA, Cloetingh S (1991) Some examples and mechanical aspects of continental lithospheric folding. Tectonophysics 188:27–37

Tejero R, Ruiz J (2002) Thermal and mechanical structure of the central Iberian Peninsula lithosphere. Tectonophysics 350:49–62

Tesauro M, Kaban MK, Cloetingh S (2009) A new thermal and rheological model of the European lithosphere. Tectonophysics 476:478–495

Tesauro M, Kaban MK, Cloetingh S (2010) 3D crustal model of Western and Central Europe as a basis for modelling mantle structure. In: Cloetingh S, Negendank J (eds) New frontiers in integrated solid earth sciences. International year of planet earth. Springer, Dordrecht. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-2737-5_2

Torne M, Fernàndez M, Vergés J, Ayala C, Salas M, Jimenez-Munt I, Buffett G, Díaz J (2015) Crust and mantle lithospheric structure of the Iberian Peninsula deduced from potential field modeling and thermal analysis. Tectonophysics 663:419–433. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2015.06.003

Van Wees JD, Beekman F (2000) Lithosphere rheology during intraplate extension and compression: inferences from automated forward modelling of subsidence data. Tectonophysics 320:219–242

Van Wees JD, Cloetingh S, De Vicente G (1996) The role of pre-existing weak zones in basin evolution: constraints from 2D finite element and 3D flexure modelling. In: Buchanan PG, Nieuwland DA (eds) Geological Society Special Publication, pp 297–320

Van Wees JD, Bergen F, David P, Nepveu M, Beekman F, Cloetingh S, Bonté D (2009) Probabilistic Tectonic heat flow modelling for basin maturation: method and applications. J Mar Petrol Geol 26:536–551. doi:10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2009.01.020

Wassing B, Van Wees JD, Fokker P (2014) Coupled continuum modeling of fracture reactivation and induced seismicity during enhanced geothermal operations. Geothermics 52:153–164

Xu Y, Shankland TJ, Linhardt S, Rubie DC, Langenhorst F, Klasinski K (2004) Thermal diffusivity and conductivity of olivine, wadsleyite and ringwoodite to 20 GPa and 1373 K. Phys Earth Planet Inter 143–144:321–336

Ziegler PA, Cloetingh S, van Wees JD (1995) Dynamics of intraplate compressional deformation: the Alpine foreland and other examples. Tectonophysics 252:7–59

Ziegler PA, van Wees JD, Cloetingh S (1998) Mechanical controls on collision related compressional intraplate deformation. Tectonophysics 300:103–129

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme under Grant Agreement No. 608553 (Project IMAGE). We thank the editor and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments that helped us to improve the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Limberger, J., Bonte, D., de Vicente, G. et al. A public domain model for 1D temperature and rheology construction in basement-sedimentary geothermal exploration: an application to the Spanish Central System and adjacent basins. Acta Geod Geophys 52, 269–282 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40328-017-0197-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40328-017-0197-5