Abstract

Background

Menstrual cycle (MC) disorders and MC-related symptoms can have debilitating effects on the health and performance of female athletes. As the participation of women in sports continues to increase, understanding the prevalence of a range of MC disorders and MC-related symptoms may guide preventive strategies to protect the health and optimise the performance of female athletes.

Objective

To examine the prevalence of MC disorders and MC-related symptoms among female athletes who are not using hormonal contraceptives and evaluate the assessment methods used to identify MC disorders and MC-related symptoms.

Methods

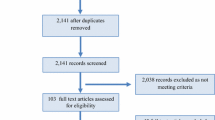

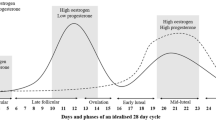

This systematic review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). Six databases were searched until September 2022 for all original research that reported the prevalence of MC disorders and/or MC-related symptoms in athletes not using hormonal contraceptives, which included the definitions of the MC disorders examined, and the assessment methods used. MC disorders included amenorrhoea, anovulation, dysmenorrhoea, heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB), luteal phase deficiency (LPD), oligomenorrhoea, premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). MC-related symptoms included any affective and physical symptoms related to the MC that do not cause significant personal, interpersonal or functional impairment. The prevalence data across eligible studies were combined, and all studies were qualitatively synthesised to evaluate the assessment methods and tools used to identify MC disorders and MC-related symptoms. The methodological quality of studies was assessed using a modified Downs and Black checklist.

Results

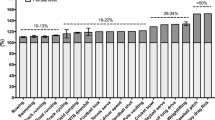

Sixty studies involving 6380 athletes were included. A wide range of prevalence was observed for all types of MC disorders, with a dearth of data on anovulation and LPD. Based on pooled data, dysmenorrhoea (32.3%; range 7.8–85.6%) was the most prevalent MC disorder. Studies reporting MC-related symptoms mostly examined the premenstrual and menstruation phases, where affective symptoms appeared more prevalent than physical symptoms. A larger proportion of athletes reported symptoms during the initial days of menstruation compared with the premenstrual phase. MC disorders and MC-related symptoms were retrospectively assessed using self-report methods in 90.0% of studies. Most studies (76.7%) in this review were graded as moderate quality.

Discussion

MC disorders and MC-related symptoms are commonplace among female athletes, warranting further research examining their impact on performance and preventive/management strategies to optimise athlete health. To increase the quality of future studies, researchers should adopt standardised definitions of MC disorders and assessment methods such as a combination of calendar counting, urinary ovulation tests and a mid-luteal phase serum progesterone measurement when assessing menstrual function. Similarly, standardised diagnostic criteria should be used when examining MC disorders such as HMB, PMS and PMDD. Practically, implementing prospective cycle monitoring that includes ovulation testing, mid-luteal blood sampling (where feasible) and symptom logging throughout the MC could support athletes and practitioners to promptly identify and manage MC disorders and/or MC-related symptoms.

Trial Registration

This review has been registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42021268757).

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

17 July 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-023-01893-2

References

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 128: Diagnosis of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding in Reproductive-Aged Women. 2012. https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Citation/2012/07000/Practice_Bulletin_No__128__Diagnosis_of_Abnormal.41.aspx. Accessed 1 Nov 2021.

Broekmans FJ, Visser JA, Laven JSE, Broer SL, Themmen APN, Fauser BC. Anti-Müllerian hormone and ovarian dysfunction. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2008;19:340–7.

Phillips NA, Bachmann G. Premenstrual syndrome and dysphoric disorder - Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment. BMJ Best Practice. 2022. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-us/419. Accessed 10 Nov 2022.

Goldman MB, Hatch MC. Women and Health. Berlin: Elsevier; 1999.

Ellison PT. Human ovarian function and reproductive ecology: new hypotheses. Am Anthropolog. 1990;92:933–52.

Bernardi M, Lazzeri L, Perelli F, Reis FM, Petraglia F. Dysmenorrhea and related disorders. F1000Res. 2017;6:1645.

Biggs WS, Demuth RH. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Am Fam Phys. 2011;84:918–24.

Manore MM. Dietary recommendations and athletic menstrual dysfunction. Sports Med. 2002;32:887–901.

Otis CL, Drinkwater B, Johnson M, Loucks A, Wilmore J. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. The Female Athlete Triad. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29:i–ix.

Nattiv A, Loucks AB, Manore MM, Sanborn CF, Sundgot-Borgen J, Warren MP. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. The female athlete triad. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1867–82.

Shufelt CL, Torbati T, Dutra E. Hypothalamic amenorrhea and the long-term health consequences. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35:256–62.

De Souza MJ, West SL, Jamal SA, Hawker GA, Gundberg CM, Williams NI. The presence of both an energy deficiency and estrogen deficiency exacerbate alterations of bone metabolism in exercising women. Bone. 2008;43:140–8.

O’Donnell E, Harvey PJ, Goodman JM, De Souza MJ. Long-term estrogen deficiency lowers regional blood flow, resting systolic blood pressure, and heart rate in exercising premenopausal women. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1401-1409.

Rickenlund A, Eriksson MJ, Schenck-Gustafsson K, Hirschberg AL. Amenorrhea in female athletes is associated with endothelial dysfunction and unfavorable lipid profile. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1354–9.

Elliott-Sale KJ, Minahan CL, de Jonge XAKJ, Ackerman KE, Sipilä S, Constantini NW, et al. Methodological considerations for studies in sport and exercise science with women as participants: a working guide for standards of practice for research on women. Sports Med [Internet]. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01435-8.

Karlsson TS, Marions LB, Edlund MG. Heavy menstrual bleeding significantly affects quality of life. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93:52–7.

Gao M, Zhang H, Gao Z, Cheng X, Sun Y, Qiao M, et al. Global and regional prevalence and burden for premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101: e28528.

Ju H, Jones M, Mishra G. The prevalence and risk factors of dysmenorrhea. Epidemiol Rev. 2014;36:104–13.

Bruinvels G, Goldsmith E, Blagrove R, Simpkin A, Lewis N, Morton K, et al. Prevalence and frequency of menstrual cycle symptoms are associated with availability to train and compete: a study of 6812 exercising women recruited using the Strava exercise app. Br J Sports Med. 2021;55:438–43.

Armour M, Parry KA, Steel K, Smith CA. Australian female athlete perceptions of the challenges associated with training and competing when menstrual symptoms are present. Int J Sports Sci Coach. 2020;15:316–23.

Warren MP, Perlroth NE. The effects of intense exercise on the female reproductive system. J Endocrinol. 2001;170:3–11.

De Souza MJ, Toombs RJ, Scheid JL, O’Donnell E, West SL, Williams NI. High prevalence of subtle and severe menstrual disturbances in exercising women: confirmation using daily hormone measures. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:491–503.

Torstveit MK, Sundgot-Borgen J. The female athlete triad exists in both elite athletes and controls. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:1449–59.

McNulty KL, Elliott-Sale KJ, Dolan E, Swinton PA, Ansdell P, Goodall S, et al. The effects of menstrual cycle phase on exercise performance in eumenorrheic women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2020;50:1813–27.

Elliott-Sale KJ, McNulty KL, Ansdell P, Goodall S, Hicks KM, Thomas K, et al. The effects of oral contraceptives on exercise performance in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2020;50:1785–812.

Elliott-Sale KJ, Ross E, Burden R, Hicks K. The BASES Expert Statement on conducting and implementing female athlete-based research. Sport Exerc Sci. 2020;65:6–7.

Pitchers G, Elliott-sale K. Considerations for coaches training female athletes. Prof Strength Cond. 2019;55:19–30.

Roupas ND, Georgopoulos NA. Menstrual function in sports. Hormones (Athens). 2011;10:104–16.

De Souza MJ, Nattiv A, Joy E, Misra M, Williams NI, Mallinson RJ, et al. 2014 Female Athlete Triad Coalition consensus statement on treatment and return to play of the female athlete triad: 1st International Conference held in San Francisco, CA, May 2012, and 2nd International Conference held in Indianapolis, IN, May 2013. Clin J Sport Med. United States; 2014;24:96–119.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10:89.

Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:377–84.

McKay AKA, Stellingwerff T, Smith ES, Martin DT, Mujika I, Goosey-Tolfrey VL, et al. Defining Training and performance caliber: a participant classification framework. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2022;17:317–31.

Smith ES, McKay AKA, Ackerman KE, Harris R, Elliott-Sale KJ, Stellingwerff T, et al. Methodology review: a protocol to audit the representation of female athletes in sports science and sports medicine research. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2022;1:1–14.

Master-Hunter T, Heiman DL. Amenorrhea: evaluation and treatment. Am Family Phys. 2006;73:1374–82.

Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Current evaluation of amenorrhea. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:S219-225.

Hackney AC, Smith-Ryan AE, Fink JE. Methodological considerations in exercise endocrinology. In: Hackney AC, Constantini NW, editors. Endocrinology of physical activity and sport [Internet]. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-33376-8_1.

Klein DA, Poth MA. Amenorrhea: an approach to diagnosis and management. AFP. 2013;87:781–8.

Janse DE, Jonge X, Thompson B, Han A. Methodological recommendations for menstrual cycle research in sports and exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51:2610–7.

reVITALize: Gynecology Data Definitions. https://www.acog.org/en/practice-management/health-it-and-clinical-informatics/revitalize-gynecology-data-definitions. Accessed 1 Nov 2021.

ACOG Committee Opinion No. 760: Dysmenorrhea and endometriosis in the adolescent. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:e249–58.

Dawood MY. Primary dysmenorrhea: advances in pathogenesis and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:428–41.

Kadian S, O’Brien S. Classification of premenstrual disorders as proposed by the International Society for Premenstrual Disorders. Menopause Int. 2012;18:43–7.

Dickerson LM, Mazyck PJ, Hunter MH. Premenstrual syndrome. AFP. 2003;67:1743–52.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Lanhers C, Courteix D, Valente-Dos-Santos J, Ferry B, Gracia-Marco L, Pereira B, et al. Gonadal hormones may predict structural bone fragility in elite female soccer player. J Sports Sci. 2020;38:827–37.

Bacchi E, Spiazzi G, Zendrini G, Bonin C, Moghetti P. Low body weight and menstrual dysfunction are common findings in both elite and amateur ballet dancers. J Endocrinol Invest. 2013;36:343–6.

Barrack MT, Van Loan MD, Rauh MJ, Nichols JF. Physiologic and behavioral indicators of energy deficiency in female adolescent runners with elevated bone turnover. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:652–9.

Beals KA, Manore MM. Disorders of the female athlete triad among collegiate athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2002;12:281–93.

Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP, Hamilton LH. The relation of eating problems and amenorrhea in ballet dancers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1987;19:41–4.

Calabrese LH, Kirkendall DT, Floyd M, Rapoport S, Williams GW. Menstrual abnormalities, nutritional patterns, and body composition in female classical ballet dancers. Phys Sportsmed. 1983;11:86–90.

Cook SD, Harding AF, Thomas KA, Morgan EL, Schnurpfeil KM, Haddad RJ Jr. Trabecular bone density and menstrual function in women runners. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15:503–7.

Czajkowska M, Drosdzol-Cop A, Gałązka I, Naworska B, Skrzypulec-Plinta V. Menstrual cycle and the prevalence of premenstrual syndrome/premenstrual dysphoric disorder in adolescent athletes. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28:492–8.

Czajkowska M, Plinta R, Rutkowska M, Brzęk A, Skrzypulec-Plinta V, Drosdzol-Cop A. Menstrual cycle disorders in professional female rhythmic gymnasts. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:1470.

Dusek T. Influence of high intensity training on menstrual cycle disorders in athletes. Croat Med J. 2001;42:79–82.

Egan E, Reilly T, Whyte G, Giacomoni M, Cable NT. Disorders of the menstrual cycle in elite female ice hockey players and figure skaters. Biol Rhythm Res. 2003;34:251–64.

Fogelholm M, Van Marken LW, Ottenheijm R, Westerterp K. Amenorrhea in ballet dancers in the Netherlands. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1996;28:545–50.

Foster R, Vaisberg M, Araújo MP, Martins MA, Capel T, Bachi ALL, et al. Relationship between Anxiety and Interleukin 10 in Female Soccer Players with and Without Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS). Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2017;39:602–7.

Frisch RE, Albright T, Gotz-Welbergen AV, Witschi J, McArthur JW. Delayed menarche and amenorrhea of college athletes in relation to age of onset of training. J Am Med Assoc. 1981;246:1559–63.

Goodwin Y, Monyeki MA, Boit MK, De Ridder JH, Toriola AL, Mwangi FM, et al. Association between energy availability and menstrual function in elite Kenyan runners. Afr J Phys Health Educ Recreat Dance. 2014;20:291–307.

Guler F, Hascelik Z. Menstrual dysfunction rate and delayed menarche in top athletes of team games. Sports Med Train Rehabil. 1993;4:99–106.

Hagmar M, Berglund B, Brismar K, Hirschberg AL. Hyperandrogenism may explain reproductive dysfunction in olympic athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009;41:1241–8.

Hammar ML, Hammar-Henriksson MB, Frisk J, Rickenlund A, Wyon YA. Few oligo-amenorrheic athletes have vasomotor symptoms. Maturitas. 2000;34:219–25.

Harber VJ, Webber CE, Sutton JR, MacDougall JD. The effect of amenorrhea on calcaneal bone density and total bone turnover in runners. Int J Sports Med. 1991;12:505–8.

Hoch AZ, Pajewski NM, Moraski L, Carrera GF, Wilson CR, Hoffmann RG, et al. Prevalence of the female athlete triad in high school athletes and sedentary students. Clin J Sport Med. 2009;19:421–8.

Ihalainen JK, Kettunen O, McGawley K, Solli GS, Hackney AC, Mero AA, et al. Body composition, energy availability, training, and menstrual status in female runners. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2021;16:1043–8.

Jenkins PJ, Ibanez-Santos X, Holly J, Cotterill A, Perry L, Wolman R, et al. IGFBP-1: a metabolic signal associated with exercise-induced amenorrhoea. Neuroendocrinology. 1993;57:600–4.

Kishali NF, Imamoglu O, Katkat D, Atan T, Akyol P. Effects of menstrual cycle on sports performance. Int J Neurosci. 2006;116:1549–63.

Maïmoun L, Coste O, Georgopoulos NA, Roupas ND, Mahadea KK, Tsouka A, et al. Despite a high prevalence of menstrual disorders, bone health is improved at a weight-bearing bone site in world-class female rhythmic gymnasts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:4961–9.

Martin D, Sale C, Cooper SB, Elliott-Sale KJ. Period Prevalence and perceived side effects of hormonal contraceptive use and the menstrual cycle in elite athletes. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2018;13:926–32.

Melin A, Tornberg ÅB, Skouby S, Møller SS, Sundgot-Borgen J, Faber J, et al. Energy availability and the female athlete triad in elite endurance athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2015;25:610–22.

Möller-Nielsen J, Hammar M. Women’s soccer injuries in relation to the menstrual cycle and oral contraceptive use. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1989;21:126–9.

Molnár AH, Vidiczki-Dóczi A, Petrovszki Z, Győri F. Prevalence of eating disorders and menstrual irregularities among female football players. Arena J Phys Activ. 2016;5:16–27.

Momma R, Nakata Y, Sawai A, Takeda M, Natsui H, Mukai N, et al. Comparisons of the prevalence, severity, and risk factors of dysmenorrhea between Japanese female athletes and non-athletes in universities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;19:52.

Mukherjee P, Mishra SK, Ray S. Menstrual characteristics of adolescent athletes: a study from West Bengal, India. Coll Antropol. 2014;38:917–23.

Myburgh KH, Berman C, Novick I, Noakes TD, Lambert EV. Decreased Resting Metabolic Rate in Ballet Dancers With Menstrual Irregularity. Int J Sport Nutr. 1999;9:285.

Nichols JF, Rauh MJ, Lawson MJ, Ji M, Barkai HS. Prevalence of the female athlete triad syndrome among high school athletes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:137–42.

Nose-Ogura S, Yoshino O, Dohi M, Kigawa M, Harada M, Kawahara T, et al. Low bone mineral density in elite female athletes with a history of secondary amenorrhea in their teens. Clin J Sport Med. 2020;30:245–50.

Oxfeldt M, Dalgaard LB, Jørgensen AA, Hansen M. Hormonal contraceptive use, menstrual dysfunctions, and self-reported side effects in elite athletes in Denmark. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2020;15:1377–84.

Parker LJ, Elliott-Sale KJ, Hannon MP, Morton JP, Close GL. An audit of hormonal contraceptive use in Women’s Super League soccer players; implications on symptomology. Sci Med Footb. 2022;6:153–8.

Pollock N, Grogan C, Perry M, Pedlar C, Cooke K, Morrissey D, et al. Bone-mineral density and other features of the female athlete triad in elite endurance runners: a longitudinal and cross-sectional observational study. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2010;20:418–26.

Quah YVMS, Poh BKP, Ng LODP, Noor MIP. The female athlete triad among elite Malaysian athletes: prevalence and associated factors. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2009;18:200–8.

Roberts TA, Glen J, Kreipe RE. Disordered eating and menstrual dysfunction in adolescent female athletes participating in school-sponsored sports. Clin Pediatr. 2003;42:561–4.

Robinson TL. Bone mineral and menstrual cycle status in competitive female athletes: a longitudinal study. Oregon State University; 1996. https://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/concern/graduate_thesis_or_dissertations/gh93h161c. Accessed 6 Aug 2021.

Rutherford OM. Spine and total body bone mineral density in amenorrheic endurance athletes. J Appl Physiol. 1993;74:2904–8.

Schtscherbyna A, Soares EA, de Oliveira FP, Ribeiro BG. Female athlete triad in elite swimmers of the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Nutrition. 2009;25:634–9.

Stefani L, Galanti G, Lorini S, Beni G, Dei M, Maffulli N. Female athletes and menstrual disorders: a pilot study. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J (MLTJ). 2016;6:183–7.

Stokic E, Srdic B, Barak O. Body mass index, body fat mass and the occurrence of amenorrhea in ballet dancers. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2005;20:195–9.

Sygo J, Coates AM, Sesbreno E, Mountjoy ML, Burr JF. Prevalence of indicators of low energy availability in elite female sprinters. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2018;28:490–6.

Takeda T, Imoto Y, Nagasawa H, Muroya M, Shiina M. Premenstrual SYNDROME AND PREMENSTRUAL DYSPHORIC DISORDER in Japanese Collegiate Athletes. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28:215–8.

Takeda T, Imoto Y, Nagasawa H, Takeshita A, Shiina M. Stress fracture and premenstrual syndrome in Japanese adolescent athletes: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6: e013103.

Takeda T, Ueno T, Uchiyama S, Shiina M. Premenstrual symptoms interference and equal production status in Japanese collegiate athletes: a cross-sectional study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2018;44:488–94.

Thompson SHEC. Characteristics of the Female Athlete Triad in Collegiate Cross-Country Runners. J Am Coll Health. 2007;56:129–36.

Toriola AL. Survey of menstrual function in young Nigerian athletes. Int J Sports Med. 1988;9:29–34.

Toriola AL, Mathur DN. Menstrual dysfunction in Nigerian athletes. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1986;93:979–85.

Tsukahara Y, Torii S, Yamasawa F, Iwamoto J, Otsuka T, Goto H, et al. Bone parameters of elite athletes with oligomenorrhea and prevalence seeking medical attention: a cross-sectional study. J Bone Miner Metab. 2021;39:1009–18.

Wakat DK, Sweeney KA, Rogol AD. Reproductive system function in women cross-country runners. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14:263–9.

Yamada K, Takeda T. Low Proportion of Dietary Plant Protein among Athletes with Premenstrual Syndrome-Related Performance Impairment. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2018;244:119–22.

Feldmann JM, Belsha JP, Eissa MA, Middleman AB. Female adolescent athletes’ awareness of the connection between menstrual status and bone health. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011;24:311–4.

Muia EN, Wright HH, Onywera VO, Kuria EN. Adolescent elite Kenyan runners are at risk for energy deficiency, menstrual dysfunction and disordered eating. J Sports Sci. 2016;34:598–606.

Pavlak MJS. The inter-relatedness of nutrition, menstrual status, lean body mass, and injury among high school female varsity basketball players. Grand Valley State University; 1998. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1388&context=theses. Accessed 6 Aug 2021.

Snyder AC, Wenderoth MP, Johnston CC, Hui SL. Bone mineral content of elite lightweight amenorrheic oarswomen. Hum Biol. 1986;58:863–9.

Takeda T, Imoto Y, Nagasawa H, Takeshita A, Shiina M. Fish consumption and premenstrual syndrome and dysphoric disorder in Japanese Collegiate Athletes. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29:386–9.

Takeda T, Yoshimi K, Imoto Y, Shiina M. Associations between sleep habits and interference of premenstrual symptoms in athletic performance in Japanese adolescent athletes: a cohort study over a 2-year period. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2020;36:885–9.

Vannuccini S, Fondelli F, Clemenza S, Galanti G, Petraglia F. Dysmenorrhea and heavy menstrual bleeding in elite female athletes: quality of life and perceived stress. Reprod Sci. 2020;27:888–94.

de Oliveira FP, Bosi MLM, dos Vigário PS, Vieira da RS. Comportamento alimentar e imagem corporal em atletas. Rev Bras Med Esporte. 2003;9:348–56.

O’Brien PMS, Bäckström T, Brown C, Dennerstein L, Endicott J, Epperson CN, et al. Towards a consensus on diagnostic criteria, measurement and trial design of the premenstrual disorders: the ISPMD Montreal consensus. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14:13–21.

Proctor M, Farquhar C. Diagnosis and management of dysmenorrhoea. BMJ. 2006;332:1134–8.

Armour M, Ee CC, Naidoo D, Ayati Z, Chalmers KJ, Steel KA, et al. Exercise for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database oSyste Rev [Internet]. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004142.pub4/full.

Casey ML, MacDonald PC, Mitchell MD. Despite a massive increase in cortisol secretion in women during parturition, there is an equally massive increase in prostaglandin synthesis. A paradox? J Clin Invest. 1985;75:1852–7.

Pascoe MC, Thompson DR, Ski CF. Yoga, mindfulness-based stress reduction and stress-related physiological measures: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017;86:152–68.

Bhatia SC, Bhatia SK. Diagnosis and treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder. AFP. 2002;66:1239.

McNamara A, Harris R, Minahan C. ‘That time of the month’… for the biggest event of your career! Perception of menstrual cycle on performance of Australian athletes training for the 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2022;8: e001300.

Findlay R, Macrae E, Whyte I, Easton C, Forrest (née Whyte) L. How the menstrual cycle and menstruation affect sporting performance: experiences and perceptions of elite female rugby players. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:1108–13.

Logue CM, Moos RH. Positive perimenstrual changes: Toward a new perspective on the menstrual cycle. J Psychosom Res. 1988;32:31–40.

Riaz Y, Parekh U. Oligomenorrhea [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 [cited 2022 Mar 15]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560575/.

Nazem TG, Ackerman KE. The female athlete triad. sports. Health. 2012;4:302–11.

Mallinson R, Souza MJD. Current perspectives on the etiology and manifestation of the “silent” component of the Female Athlete Triad. Int J Women’s Health. 2014;6:451–67.

De Souza MJ. Menstrual disturbances in athletes: a focus on luteal phase defects. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1553–63.

Russell M, Misra M. Influence of ghrelin and adipocytokines on bone mineral density in adolescent female athletes with amenorrhea and eumenorrheic athletes. Med Sport Sci. 2010;55:103–13.

Barrack MT, Gibbs JC, De Souza MJ, Williams NI, Nichols JF, Rauh MJ, et al. Higher incidence of bone stress injuries with increasing female athlete triad-related risk factors: a prospective multisite study of exercising girls and women. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:949–58.

Vanheest JL, Rodgers CD, Mahoney CE, De Souza MJ. Ovarian suppression impairs sport performance in junior elite female swimmers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46:156–66.

Mansour D, Hofmann A, Gemzell-Danielsson K. A Review of clinical guidelines on the management of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in women with heavy menstrual bleeding. Adv Ther. 2021;38:201–25.

Hinton PS. Iron and the endurance athlete. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2014;39:1012–8.

Davies J, Kadir RA. Heavy menstrual bleeding: An update on management. Thromb Res. 2017;151:S70–7.

Franchini E, Brito CJ, Artioli GG. Weight loss in combat sports: physiological, psychological and performance effects. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2012;9:52.

Thomas S, Gonzalez A, Ghigiarelli J. The Relationship between weight cutting and the female athlete triad in combat sport athletes. Int J Kinesiol Sports Sci. 2021;9:9.

Gordon CM, Ackerman KE, Berga SL, Kaplan JR, Mastorakos G, Misra M, et al. Functional hypothalamic amenorrhea: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:1413–39.

Sharps FRJ, Wilson LJ, Graham CA-M, Curtis C. Prevalence of disordered eating, eating disorders and risk of low energy availability in professional, competitive and recreational female athletes based in the United Kingdom. Eur J Sport Sci. 2022;22:1445–51.

Meng K, Qiu J, Benardot D, Carr A, Yi L, Wang J, et al. The risk of low energy availability in Chinese elite and recreational female aesthetic sports athletes. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2020;17:13.

Loucks AB, Kiens B, Wright HH. Energy availability in athletes. J Sports Sci. 2011;29:S7-15.

Kuikman MA, Mountjoy M, Burr JF. Examining the relationship between exercise dependence, disordered eating, and low energy availability. Nutrients. 2021;13:2601.

Hagmar M, Berglund B, Brismar K, Hirschberg AL. Hyperandrogenism may explain reproductive dysfunction in olympic athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc United States. 2009;41:1241–8.

Althubaiti A. Information bias in health research: definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:211–7.

Small CM, Manatunga AK, Marcus M. Validity of self-reported menstrual cycle length. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:163–70.

Taffe J, Dennerstein L. Retrospective self-report compared with menstrual diary data prospectively kept during the menopausal transition. Climacteric. 2000;3:183–91.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Heavy menstrual bleeding: assessment and management. 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88. Accessed 22 Mar 2022.

Zakherah MS, Sayed GH, El-Nashar SA, Shaaban MM. Pictorial blood loss assessment chart in the evaluation of heavy menstrual bleeding: diagnostic accuracy compared to alkaline hematin. GOI Karger Publishers. 2011;71:281–4.

Higham JM, O’Brien PM, Shaw RW. Assessment of menstrual blood loss using a pictorial chart. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97:734–9.

Hald K, Lieng M. Assessment of Periodic Blood Loss: Interindividual and Intraindividual Variations of Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart Registrations. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:662–8.

Herman MC, Mol BW, Bongers MY. Diagnosis of heavy menstrual bleeding. Womens Health (Lond Engl). 2016;12:15–20.

Magnay JL, O’Brien S, Gerlinger C, Seitz C. Pictorial methods to assess heavy menstrual bleeding in research and clinical practice: a systematic literature review. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20:24.

Sokol ER, Casele H, Haney EI. Ultrasound examination of the postpartum uterus: what is normal? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004;15:95–9.

Hofmeister S, Bodden S. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder. AFP. 2016;94:236–40.

Diaz A, Laufer MR, Breech LL, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Adolescent Health Care. Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2245–50.

Jamieson MA. Disorders of Menstruation in Adolescent Girls. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2015;62:943–61.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 136: Management of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding Associated With Ovulatory Dysfunction. 2013. https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Citation/2013/07000/Practice_Bulletin_No__136__Management_of_Abnormal.38.aspx. Accessed 1 Nov 2021.

Armour M, Dahlen HG, Smith CA. More than needles: the importance of explanations and self-care advice in treating primary dysmenorrhea with acupuncture. Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2016;2016:3467067.

As-Sanie S, Black R, Giudice LC, Gray Valbrun T, Gupta J, Jones B, et al. Assessing research gaps and unmet needs in endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:86–94.

Hudelist G, Fritzer N, Thomas A, Niehues C, Oppelt P, Haas D, et al. Diagnostic delay for endometriosis in Austria and Germany: causes and possible consequences. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:3412–6.

Ramos-Pichardo JD, Ortega-Galán ÁM, Iglesias-López MT, Abreu-Sánchez A, Fernández-Martínez E. Why do some spanish nursing students with menstrual pain fail to consult healthcare professionals? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:8173.

Frankovich RJ, Lebrun CM. Menstrual cycle, contraception, and performance. Clin Sports Med. 2000;19:251–71.

Lethaby A, Wise MR, Weterings MA, Rodriguez MB, Brown J. Combined hormonal contraceptives for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000154.pub3/full.

Davis AR, Westhoff C, O’Connell K, Gallagher N. Oral contraceptives for dysmenorrhea in adolescent girls: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:97–104.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was funded by the Technological University of the Shannon: Midlands Midwest and the Irish Research Council under grant number GOIPG/2022/2230 awarded to Bernadette Cherianne Taim.

Conflicts of Interest

Bernadette Cherianne Taim, Ciarán Ó Catháin, Michèle Renard, Kirsty Jayne Elliot-Sale, Sharon Madigan and Niamh Ní Chéilleachair declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Availability of Data and Material

The data analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

BCT, MR and COC conceptualised the design of this study. BCT and MR conducted the literature search, screening and data extraction. BCT conducted the formal analysis. BCT, COC and NNC interpreted the data analysis. BCT wrote the manuscript with critical input from COC, KES, SM, NNC and MR. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Additional information

The original article has been updated: Due to co-author name update.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Taim, B.C., Ó Catháin, C., Renard, M. et al. The Prevalence of Menstrual Cycle Disorders and Menstrual Cycle-Related Symptoms in Female Athletes: A Systematic Literature Review. Sports Med 53, 1963–1984 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-023-01871-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-023-01871-8