Abstract

Every women’s and men’s world records from 5 km to the marathon has been broken since the introduction of carbon fibre plate (CFP) shoes in 2016. This step-wise increase in performance coincides with recent advancements in shoe technology that increase the elastic properties of the shoe thereby reducing the energy cost of running. The latest CFP shoes are acknowledged to increase running economy by more than 4%, corresponding to a greater than 2% improvement in performance/run time. The recently modified rules governing competition shoes for elite athletes, announced by World Athletics, that includes sole thickness must not exceed 40 mm and must not contain more than one rigid embedded plate, appear contrary to the true essence and credibility of sport as access to this performance-defining technology becomes the primary differentiator of sporting performance in elite athletes. This is a particular problem in sports such as athletics where the primary sponsor of the athlete is very often a footwear manufacturing company. The postponement of the 2020 Summer Olympics provides a unique opportunity for reflection by the world of sport and time to commission an independent review to evaluate the impact of technology on the integrity of sporting competition. A potential solution to solve this issue can involve the reduction of the stack height of a shoe to 20 mm. This simple and practical solution would prevent shoe technology from having too large an impact on the energy cost of running and, therefore, determining the performance outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Recent improvements in long-distance running world records are unlikely physiological but rather technological, if for no other reason that such a step-wise improvement in physiological attributes underpinning performance is unlikely. On the other hand, there has been such a step improvement in shoe technology. |

Current shoe designs for road running, and more recently for track running, that include a CFP seem to greatly reduce the energy cost of running and, as a consequence, most long-distance road running records have been broken in the last 3 years by athletes wearing CFP shoes. |

Current rules are therefore no longer fit for purpose, requiring revision to safeguard the integrity of sport. A potential solution to solve this issue can involve the reduction of the stack height of a shoe to 20 mm. |

1 Background

On 12th October 2019, Kenyan athlete Eliud Kipchoge ran 42.2 km in 1:59:40 h:min:sec, racing in personalised carbon fibre plate (CFP) shoes (i.e., Nike Alphafly) in an unofficial event in Vienna [1]. The following day, Eliud’s compatriot, Brigid Kosgei ran 2:14:04 h:min:sec in the Chicago marathon using Nike prototype CFP shoes, breaking Paula Radcliffe’s 16-year-old women’s marathon record by over a minute [2]. Kosgei’s previous personal best times were 2:18:35 h:min:sec and 2:18:20 h:min:sec set at the 2018 Chicago and 2019 London marathons, respectively [3, 4]. Since the launch of CFP shoes by Nike in 2016, the men’s and women’s world records in long-distance road running (i.e., from 5 km to the marathon) have all been broken by athletes wearing CFP shoes (Table 1), raising concerns that the introduction of this technology leads to a distinct non-physiological advantage. Notably, the first spikes including a full-length rigid plate within the midsole were introduced by Nike at the 2020 Diamond League in Monaco (14th of August 2020), and their impact was immediate [5]. Of the 65 athletes competing in races between 800 and 5000 m, 50 athletes wore Nike spikes, and 40 of these athletes wore the new spiked shoes [6]. During this event, the 5000 m male world record was broken by an athlete wearing the new spikes; a record that had stood for 16 years [7]. Two months later during a race in Valencia, this same athlete broke the 15-year-old world record in the men’s 10,000 m wearing the same spiked shoe (Table 1) [8]. This event in Valencia also saw Ethiopian athlete Letesenbet Gidey break the 12-year-old world record in the women’s 5000 m (Table 1) [8]. This situation has led some athletes to take drastic measures, for example, a well-known Spanish marathoner who holds the third fastest Spanish marathon time: 2:07:27 h:min:sec, chose to break his Adidas contract to use a Nike CFP shoe and subsequently qualified for Tokyo 2020 [9]. In response to the performance advantage experienced by athletes wearing CFP shoes designed by Nike, other companies have reacted by designing their own CFP shoes aiming to provide their athletes with a competitive advantage (shoe models displayed in Table 2).

2 Carbon-Fibre Plate Shoes and Running Performance

While the true impact of CFP shoes on running performance remains to be scientifically tested in the field, there are indications that the recent improvements in long-distance running times are unlikely to be biologically driven. Three main strategies have been proposed to reduce mechanical energy during exercise and therefore increase physical performance: (a) to optimise the musculoskeletal system, (b) to maximise the energy returned, and (c) to minimise the energy loss or absorption [61, 62]. Previous studies [63, 64] have demonstrated that flexion of the forefoot or metatarsophalangeal joint during running induces greater energy loss, resulting in reduced running and jumping energy costs when increasing the midsole longitudinal bending stiffness of a shoe and reducing the range of motion of the metatarsophalangeal joint. The current shoe technology including both CFP and thick but light midsoles (especially those composed of a polyamide block amide, PEBA [65]) are designed for increased energy return [66, 67] mediated by the action of passive elastic recoil, requiring less energy per step [68]. To obtain a more detailed image, our group performed a computed tomography scan of the CFP shoe that was used to win the 2016 Berlin marathon (shown in Fig. 1). The success of CFP shoes is reflected in public race reports and shoe records from the social-fitness network Strava. This network, containing hundreds of thousands marathon performances, shows that CFP shoes provide a 3–4% advantage over “traditional” running shoes [69]. Guinness et al. [70] observed in 578 elite marathoners (308 males, 270 females) that switching to CFP running shoes resulted in 75% of men running 1.5–2.9% faster (from 2 to 4 min) and 71% of women running 0.8–2.4% faster (from 1 to 4 min) during a marathon. These findings are consistent with an observational experiment by our group, in which we determined the effects of wearing CFP shoes (Vaporfly NEXT%) compared with “traditional” race shoes by the same manufacturer on 10 km performance in a semi-elite female athlete in 40 + age category. This athlete ran a total of six 10 km races over similar courses (three wearing a race shoe without a CFP, and three in the Nike NEXT%, in a randomised order) with a minimum of 2 weeks between races, and maintaining her habitual training load throughout this period. The courses were flat and at sea-level, and the CFP shoe elicited a 2.3% improvement over the “traditional” racing shoe (mean time: 39:04 min:sec vs. 40:03 min:sec, respectively). Notably, running cadence was identical (195 steps min−1), but stride length was 5 cm longer in the CFP shoe.

Supplementary material (MPG 473 kb).

Laboratory studies have reported improvements of approximately 4% in running economy (RE) while exercising in CFP shoes at a submaximal intensity (commonly between 14 and 18 km h−1) during a period of approximately 5 min [66, 71, 72]. Notably, large inter-individual differences in this important proxy of running performance have also been observed, with some runners experiencing no improvements in RE and others showing up to 6.4% [72]. This wide range of response in RE to CFP shoes seems to depend upon foot strike patterns and the different optimal shoe stiffness for different runners [12]. This inter-individual response to CFP shoes represents a priority area of future research. In our laboratory, the RE of an Olympic and current male world record holder improved by 2.6% when running on a treadmill at 21 km h−1 for 3 min while wearing a shoe containing a CFP compared with his previous preferred racing shoe. Notably, this athlete’s personal best in the marathon has improved by 2.7% in the 4 years since transitioning to CFP shoes.

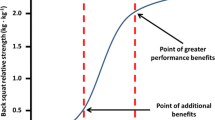

RE is highly influenced by anatomical and biomechanical differences [73], for example an increased lower-limb length due to a greater stack height of a running shoe will enhance RE when body mass is maintained [74]. Although the precise mechanisms are not clear [75], longer and thinner legs seem to contribute to a greater moment of inertia and therefore a reduced muscular demand to move the legs forward [76]. While increasing stride length has been observed to be more efficient than increasing stride frequency by devoting less energy to leg acceleration, longer legs have shown to favour longer stride length and therefore a better RE [76, 77]. In addition to improved RE by increasing leg length, a greater stack height provides an increased spring space within the shoe for more elastic energy to be stored and released during every foot-strike. For example, the 8 mm (from 23 to 31 mm) increase in effective leg length of the Vaporfly 4% shoe compared to its predecessor (i.e., Nike Streak) is thought to explain about 25% improvement provided by the Nike Vaporfly 4% [65]. This is based on a biomechanical model (i.e., the LiMb model) linking limb length to cost of transport in terrestrial animals [78, 79]. For running, this model derives the rate of muscular force production during running from effective limb length, the excursion angle of the limb during stance phase, and the energy cost of swinging the limb [80]. Although stack height is scaled according to shoe size, this is not linear and provides shorter athletes a disproportionally larger increase in lower leg length, which has been suggested to be a beneficial contributor to RE [75]. The newly released Nike Alphafly offers an additional 9 mm leg length and spring space (40 mm) and can be expected to further enhance RE by more than 4%. The energetic advantage of such CFP shoes is non-physiological and more in line with benefits derived from exoskeletons, blades and prosthetics limbs. While invariably CFP shoes improve running performance, there are no longitudinal studies advocating an increased risk of injury due to a more rigid/stiff sole [81]. However, an experienced marathoner with the second fastest marathon of all time, was forced to withdraw from the 2020 London marathon claiming his use of CFP shoes caused him several injuries due to the lack of foot stability [82]. Future research should also focus on the study of injury risk when using CFP shoes by developing standard testing protocols to identify optimal forefoot stiffness and stability depending on competitive level, individual foot strike patterns and running distances. The outcome of this research should also inform the shoe regulations.

3 Issues with Current Regulation

The magnitude of race performance improvements by athletes running in CFP shoes are analogous to those expected from various blood doping substances and methods included on the prohibited list of the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), such as erythropoietin, which have been shown to improve performance by 4–6% [83, 84]. On 31st January 2020, World Athletics reacted to this controversy in shoe technology by announcing new rules stating that sole thickness of a marathon shoe must not exceed 40 mm (25 mm for spiked shoes) and must be on sale for at least 4 months before they can be used in competition [85]. Soon after, Nike launched the Alphafly shoe with a 40 mm sole, a CFP insert, and the addition of air pods in the metatarsal region [86]. The close proximity of the Alphafly launch to the new regulation announcement raised concerns that the rules had been drafted to “legitimise” Nike’s CFP shoe series in response to accusations of “technological doping” [87], doing little to protect the principle of fairness in sporting competition. More recently WA approved a change to its rules governing development/prototype shoes following requests by the major shoe manufacturers and their representative industry body, the World Federation of the Sports Goods Industry (WFSGI) [88]. This amendment allows development shoes to be worn in international competitions prior to their availability to other athletes, upon approval of the shoe specifications by WA. These shoes will need to meet the same technical specifications as all other approved shoes. These new rules have resulted in a footwear arms race to develop patented CFP inserts by numerous shoe companies (Table 2). This is contrary to another important principle of fairness in sport—the universality of sport, where technological developments used by athletes need to be reasonably available to all competitors [85]. The cost of these shoes (shown in Table 2) would limit its availability only to a minority of athletes, being inaccessible for the largest sections of society especially from underdeveloped countries, ironically alienating many East Africans, who have dominated long-distance running worldwide for more than 50 years.

4 A Solution Towards Equity and Fairness in Sport

The sudden improvements in performance times witnessed since the emergence of CFP shoes in 2016 seem technologically driven rather than physiological, as recently suggested [89]. Joyner et al. recently discussed the different factors potentially explaining the fast marathons witnessed during the last few years [89]. Physiological and training factors in addition to shoe technology and drafting are proposed as the main contributors to recent official and unofficial (i.e., exhibitions in Monza and Vienna) fast marathons. However, the abrupt drop in world records across all distances since the launch of CFP shoes suggest that shoe technology may have a greater role than the other proposed factors (i.e., since 2017, training methods or the physiology of the athletes are unlikely to have produced such fast marathons). Drafting is undoubtedly another factor influencing the energy cost of running, although this strategy has already been employed during official races much earlier than 2017, which suggests drafting could not explain the plethora of world records witnessed during the last 3 years. The International Olympic Committee recently announced a 1-year postponement of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics due to the COVID-19 pandemic [90]. This delay provides the opportunity for World Athletics to commission an independent review focusing on technological fairness to systematically evaluate the impact of technology on the essence and integrity of sporting competition. The controversy today surrounding the “legality” and “ethics” of CFP shoes is not unprecedented. In 2009, the International Swimming Federation (FINA) was obliged to modify the rules and ban full-body swimsuits in response to numerous sudden world records broken by swimmers wearing this technology [91]. Similarly, the IAAF (now World Athletics) faced their own technological issue with shoe designs in the 1960s. Both the 200 and 400 m world records were broken within the space of 2 weeks in 1968, with both athletes wearing the newly developed “brush” shoe [92]. This shoe contained 68 small pins, compared with the traditional four or six spike shoes and appeared to improve grip and stability on a racetrack. The advantage of this technology was later confirmed in a study that reported improvements in running performance in five out of six athletes tested [93]. The breaking of two world records within a short time period led to the banning of this technological advancement by the athletics governing body and the records broken with these shoes sponged from the records [92]. The recent decision to permit the use of CFP shoes throughout the sport of athletics (including track) is contrary to previous decisions of this governing body regarding footwear innovations; a decision that must be urgently and carefully reconsidered. A potential solution to solve this issue can involve the reduction of the stack height of a shoe to 20 mm. This simple and practical solution would prevent shoe technology from having too large an impact on the energy cost of running and, therefore, determining the performance outcome. Companies would be able to innovate within this space, but shoe technology would not be the primary differentiator of sporting performance in elite athletes.

References

INEOS 1:59 Challenge [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 10]. https://www.ineos159challenge.com/.

I can go quicker, says Brigid Kosgei after smashing Paula Radcliffe’s world record |Sport| The Guardian [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 10]. https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2019/oct/13/brigid-kosgei-world-marathon-record-paula-radcliffe-chicago.

Brigid Kosgei Wins 2018 Bank of America Chicago Marathon Women’s Race—NBC Chicago [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 10]. https://www.nbcchicago.com/news/sports/chicago-marathon/chicago-marathon-2018-womens-winner-kosgei-dereje/49990/.

London Marathon 2019: Eliud Kipchoge and Brigid Kosgei Dominate—The New York Times [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 10]. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/28/sports/london-marathon-2019.html.

Results: 2020 Herculis Monaco Diamond League |Watch Athletics [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 10]. https://www.watchathletics.com/article/11192/results-2020-herculis-monaco-diamond-league.

Everything we know about Nike’s newly-released plated spikes—Canadian Running Magazine [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 1]. https://runningmagazine.ca/sections/gear/everything-we-know-about-nikes-newly-released-plated-spikes/.

Joshua Cheptegei breaks 16-year 5,000m world record at Diamond League [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 10]. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/athletics/2020/08/14/joshua-cheptegei-breaks-16-year-5000m-world-record-diamond-league/.

Cheptegei and Gidey break world records in Valencia |News [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 10]. https://www.worldathletics.org/news/report/cheptegei-gidey-valencia-world-records.

The great success of Javi Guerra, the marathoner who broke up with Adidas to run with the “magic” Vaporfly—Teller Report [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 10]. https://www.tellerreport.com/sports/2020-02-23---the-great-success-of-javi-guerra--the-marathoner-who-broke-up-with-adidas-to-run-with-the--magic--vaporfly-.rkjorDeV8.html.

World Athletics [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.worldathletics.org/records/by-category/world-records.

Joshua Cheptegei’s dominant 5k World Record! || 12:51—WOW!!—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s4dCbp1EFf0.

Joshua Cheptegei 12:35 5000m World Record!!!—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TO3IHDiUARc.

Rhonex Kipruto 10km Road World Record 26:24 [HD]—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7s_uVI9ob7A&t=1582s.

10K World Record: Joshua Cheptegei 26:11 [full race]—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TNaOQBC9gGo.

Joshua Cheptegei World Record at 2018 Zevenheuvelenloop 15 km—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lER_CfDKlCY.

Copenhagen Half Marathon 2019 new World Record!—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bhXRKwEieIw.

Men One Hour Mo Farah World Record 2020 Diamond League Brussels—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4r1jsyKho8o.

Eliud Kipchoge 2018 Berlin Marathon World Record—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GpBZhK5Kpd0.

Monaco Run 2019 |2 World Records—5 km Herculis—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bp3YodtONZA.

5K World Record Letesenbet Gidey 14:06 [full race]—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g3ZSkjojnXA.

Joyciline Jepkosgei 10K World Record at Birell Prague Grand Prix 2017—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fAeTE5sFfSE.

15K World Record 2019 | Letesenbet Gidey—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qsdtJIK5dfQ.

New Women’s half marathon World Record! | Rak Half Marathon 2020 | Ababel Brihane—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=viuzcLv-fm4.

New Women’s Only Half Marathon World Record—Peres Jepchirchir—Gdynia, Poland 2020—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9k7iYbcRINc.

Sifan Hassan beats Brigid Kosgei to the 1-Hour World Record!—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eDHToL1nPH4.

Chicago Marathon World Record | Brigid Kosgei 2:14:04!—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kn3y50MRGjY.

Keitany sets new world record in women’s marathon—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Skr7sGWVDmA.

Adidas Adizero Adios PRO | Todo lo que debes saber [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.sport.es/labolsadelcorredor/adidas-adizero-adios-pro/.

Adidas Adizero Adios Pro Review—Doctors of running [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.doctorsofrunning.com/2020/07/adidas-adizero-adios-pro-initial-review.html.

Zapatilla de running Adizero Adios Pro—Blanco adidas | adidas España [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.adidas.es/zapatilla-de-running-adizero-adios-pro/FX1765.html.

Pebax Powered® | Innovative Sports Equipment | Stretch Your LimitsTM [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.pebaxpowered.com/en/.

Nike Air Zoom Alphafly Next% Review | Running Shoes Guru [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.runningshoesguru.com/2020/09/nike-air-zoom-alphafly-next-review/.

Nike Air Zoom Alphafly NEXT% Review—Doctors of running [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.doctorsofrunning.com/2020/09/nike-air-zoom-alphafly-next-review.html.

Nike Air Zoom Alphafly NEXT% Zapatillas de competición—Hombre. Nike ES [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.nike.com/es/t/air-zoom-alphafly-next-zapatillas-de-competicion-KQKNTf/CI9925-800.

Nike ZoomX Vaporfly NEXT% Performance Review. Believe in the Run [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.believeintherun.com/2019/08/06/nike-vaporfly-next-performance-review/.

Nike ZoomX Vaporfly Next% Overview | Running Shoes Guru [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.runningshoesguru.com/overview/nike-zoomx-vaporfly-next/.

Nike ZoomX Vaporfly NEXT% Zapatillas de running. Nike ES [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.nike.com/es/t/zoomx-vaporfly-next-zapatillas-de-running-T5qg9m/AO4568-800.

Nike ZoomX Dragonfly zapatillas de running con clavos—HO20—Haz tu pedido hoy y ahorra | SportsShoes.com [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.sportsshoes.com/es-es/producto/nik17319/nike-zoomx-dragonfly-zapatillas-de-running-con-clavos-~-ho20/.

Nike ZoomX Dragonfly Unisex White | 21RUN [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://21run.com/eu/nike-zoomx-dragonfly-unisex-cv0400-100.

Joshua Cheptegei’s 12:35 5,000 Meter World Record shoes are impossibly Good | Nike ZoomX Dragonfly—YouTube [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qyrLyfe-b_A.

Nike ZoomX Dragonfly Unisex Spikes Black/Blue [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.runningwarehouse.com/Nike_ZoomX_Dragonfly_Unisex_Spikes/descpage-NZMZD01.html.

Nike Air Zoom Victory Unisex Spikes White/Crimson/Blk [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.runningwarehouse.com/Nike_Air_Zoom_Victory_Unisex_Spikes/descpage-NZVUS01.html.

Saucony Endorphin Pro Multiple Tester Review—Doctors of running [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.doctorsofrunning.com/2020/03/saucony-endorphin-pro-review.html.

Men’s Endorphin Pro—Endorphin Pro | Saucony [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.saucony.com/en/endorphin-pro/44571M.html?dwvar_44571M_color=S20598-10#start=1.

Las 10 partes de unas Asics—Running [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://running.es/las-10-partes-de-unas-asics/.

Asics Metaracer Performance Review. Believe in the Run [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.believeintherun.com/2020/03/31/asics-metaracer-performance-review/.

Asics MetaRacer: Características—Zapatillas Running | Runnea [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 30]. https://www.runnea.com/zapatillas-running/asics/metaracer/6391/.

Skechers GOrun Speed Elite Hyper Review | Running Shoes Guru [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 2]. https://www.runningshoesguru.com/2020/03/skechers-gorun-speed-elite-hyper-review/.

Skechers—Skechers GOrun Speed Elite Hyper [Internet]. https://www.skechers.com/men/shoes/skechers-gorun-speed-elite-hyper/55221.html.

Brooks Hyperion Elite—Análisis a fondo y opiniones en Foroatletismo.com [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 2]. https://www.foroatletismo.com/zapatillas/brooks-hyperion-elite/.

Brooks Hyperion Elite | Unisex Running Shoes | Brooks Running [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 2]. https://www.brooksrunning.com/en_us/hyperion-elite-unisex-running-shoe/100032.html.

Brooks Hyperion Elite 2: Características y review—Foroatletismo.com [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 2]. https://www.foroatletismo.com/zapatillas/brooks-hyperion-elite-2/.

Brooks Hyperion Elite 2 | Unisex Running Shoes | Brooks Running [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 2]. https://www.brooksrunning.com/en_us/hyperion-elite-2-unisex-running-shoe/100037.html.

New Balance FuelCell RC Elite Review | Running Shoes Guru [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.runningshoesguru.com/2020/10/new-balance-fuelcell-rc-elite-review/.

Road Trail Run: New Balance FuelCell RC Elite Multi Tester Review: A Balanced, Satisfying and Smooth Blend of Performance, Light Weight, and Comfort [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.roadtrailrun.com/2020/09/new-balance-fuelcell-rc-elite-multi.html.

Las Fuel Cell RC Elite de New Balance para conquistar el maratón [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.runnersworld.com/es/zapatillas-correr-material-deportivo/a31034273/zapatillas-new-balance-fuel-cell-rc-elite-running-opiniones/.

Running Shoe Reviews: ON Cloudboom—Runner’s Tribe [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.runnerstribe.com/shoe-reviews/running-shoe-reviews-on-cloudboom/.

Cloudboom: carbon fiber plate racing shoes | On [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.on-running.com/es-es/products/cloudboom.

Hoka One One Carbon X | Shoe Reviews [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.runnersworld.com/gear/a27495253/hoka-one-one-carbon-x/.

Carbon X [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.hokaoneone.eu/es/es/hombre-caminata/carbon-x/1102886.html?dwvar_1102886%09_color=ABEP.

Nigg BM, Segesser B. Orthopedic and biomechanical concepts of sports shoe construction. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;24:595–602.

Nigg BM, Stefanyshyn D, Denoth J. Mechanical considerations of work and energy. Biomech Biol Mov. 2000;5–18.

Stefanyshyn D, Fusco C. Increased shoe bending stiffness increases sprint performance. Sport Biomech. 2004;3:55–66.

Stefanyshyn DJ, Nigg BM. Mechanical energy contribution of the metatarsophalangeal joint to running and sprinting. J Biomech. 1997;30:1081–5.

Burns GT, Tam N. Is it the shoes? A simple proposal for regulating footwear in road running. Br J Sport Med. 2019;bjsports-2018-100480.

Hoogkamer W, Kipp S, Frank JH, Farina EM, Luo G, Kram R. A comparison of the energetic cost of running in marathon racing shoes. Sports Med. 2018;48:1009–19.

Wang L, Hong Y, Li JX. Durability of running shoes with ethylene vinyl acetate or polyurethane midsoles. J Sports Sci. 2012;30:1787–92.

Weyand PG. Now Afoot: engineered running economy. J Appl Physiol. 2020;128:1083.

Kealy K, Katz J. Nike Says Its $250 Running Shoes Will Make You Run Much Faster. What if That’s Actually True? [Internet]. New York Times. 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/section/upshot.

Guinness J, Bhattacharya D, Chen J, Chen M, Loh A. An observational study of the effect of Nike Vaporfly shoes on marathon performance. arXiv. 2020.

Barnes KR, Kilding AE. A randomized crossover study investigating the running economy of highly-trained male and female distance runners in marathon racing shoes versus track spikes. Sports Med. 2019;49:331–42.

Hunter I, McLeod A, Valentine D, Low T, Ward J, Hager R. Running economy, mechanics, and marathon racing shoes. J Sport Sci. 2019;37:2367–73.

Raichlen DA, Armstrong H, Lieberman DE. Calcaneus length determines running economy: implications for endurance running performance in modern humans and Neandertals. J Hum Evol. 2011;60:299–308.

Steudel-Numbers KL, Weaver TD, Wall-Scheffler CM. The evolution of human running: effects of changes in lower-limb length on locomotor economy. J Hum Evol. 2007;53:191–6.

Lucia A, Esteve-Lanao J, Oliván J, Gómez-Gallego F, San Juan AF, Santiago C, et al. Physiological characteristics of the best Eritrean runners—exceptional running economy. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2006;31:530–40.

Mooses M, Mooses K, Haile DW, Durussel J, Kaasik P, Pitsiladis YP. Dissociation between running economy and running performance in elite Kenyan distance runners. J Sport Sci. 2015;33:136–44.

Sleivert GG, Rowlands DS. Physical and physiological factors associated with success in the triathlon. Sports Med. 1996;22(1):8–18.

Pontzer H. A new model predicting locomotor cost from limb length via force production. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:1513–24.

Pontzer H. Predicting the energy cost of terrestrial locomotion: a test of the LiMb model in humans and quadrupeds. J Exp Biol. 2007;210:484–94.

Pontzer H. Effective limb length and the scaling of locomotor cost in terrestrial animals. J Exp Biol. 2007;210:1752–61.

Sun X, Lam WK, Zhang X, Wang J, Fu W. Systematic review of the role of footwear constructions in running biomechanics: implications for running-related injury and performance. J Sport Sci Med. 2020;19(1):20–37.

London Marathon: Kenenisa Bekele to miss race because of injury—BBC Sport [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 3]. https://www.bbc.com/sport/athletics/54386018.

Haile DW, Durussel J, Mekonen W, Ongaro N, Anjila E, Mooses M, et al. Effects of EPO on blood parameters and running performance in Kenyan Athletes. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2019;51:299–307.

Durussel J, Daskalaki E, Anderson M, Chatterji T, Wondimu DH, Padmanabhan N, et al. Haemoglobin mass and running time trial performance after recombinant human erythropoietin administration in trained men. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e56151.

World Athletics. World Athletics modifies rules governing competition shoes for elite athletes [Internet]. [cited 2020 Feb 17]. https://www.worldathletics.org/news/press-release/modified-rules-shoes.

Alphafly NEXT%. Nike.com [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 10]. https://www.nike.com/running/alphafly.

Kelland K. Nike Vaporflys: World Athletics set to clamp down on ‘technological doping’ | The Independent [Internet]. [cited 2020 Apr 2]. https://www.independent.co.uk/sport/general/athletics/nike-vaporflys-world-athletics-record-rules-soles-latest-news-a9299951.html.

https://www.worldathletics.org/news/press-releases/amendment-to-development-shoe-rules-in-international-competitions. Accessed 30 Dec 2020

Joyner MJ, Hunter SK, Lucia A, Jones AM. Physiology and fast marathons. J Appl Physiol. 2020;128:1065–8.

Olympic Games postponed to 2021 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 10]. https://tokyo2020.org/en/news/joint-statement-from-international-olympic-committee-and-tokyo2020.

Full Body Swimsuit Now Banned for Professional Swimmers—ABC News [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 10]. https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/full-body-swimsuit-now-banned-professional-swimmers/story?id=9437780.

The Puma shoe that upended the 1968 Olympics and threatened Adidas—Sports Illustrated [Internet]. [cited 2020 Sep 24]. https://www.si.com/track-and-field/2019/11/15/puma-shoe-upended-1968-olympics.

Wood DW. An experimental test of the Puma Model Number 296 Brush Spike Shoe and the Mexico Puma Model Number 295 Standard Four Spike shoe as to their effect on sprint running. Ohio University; 1972.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this article.

Conflict of interest

One of the authors, YP, is the founding member of the Sub2 project (http://www.sub2hrs.com). Author SS is a PhD student partly funded by the Sub2hrs project. None of the authors are paid consultants or have ownership of any patents linked to the present review.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

BMP, SS and YP: conceived the idea of this review and wrote the first draft. KA, FMG and AB: significantly contributed during further drafts and all authors read and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Muniz-Pardos, B., Sutehall, S., Angeloudis, K. et al. Recent Improvements in Marathon Run Times Are Likely Technological, Not Physiological. Sports Med 51, 371–378 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01420-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-020-01420-7