Abstract

Background

Self-reported outcome measures of athlete health, wellbeing and performance add information to that obtained from clinical measures. However valid, universally accepted outcome measures are required.

Objective

To determine which athlete-reported outcome measures of performance have been used to measure the impact of injury and illness on performance in sport and assess evidence to support their validity.

Methods

The authors searched Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, CINAHL Plus, SPORTDiscus with Full Text and Cochrane library to January 2016. Predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied and papers included if an outcome measure of performance, assessed in relation to illness, injury or a related intervention, was reported by an elite, adult, able-bodied athlete. A checklist was used to assess eligible outcome measures for aspects of validity. Reporting of this study was guided by PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews.

Results

Twenty athlete-reported outcome measures in 21 papers were identified. Of these 20, only four cited validation. Of these four, three reported evidence to support validity in elite athlete groups as defined by the predetermined checklist. Fifteen patient-reported outcome measures were identified, of which four demonstrated validity in young athletic populations.

Conclusions

Most athlete-reported outcome measures of performance have been designed for individual studies with no reported assessment of validity. Despite some limitations, the Oslo Sports Trauma Centre overuse injury questionnaire demonstrates validity and potential utility to investigate the self-reported impact of pre-defined conditions on athletic performance across different sports.

Similar content being viewed by others

Valid self-reported outcome measures can contribute to a greater understanding of the impact of illness and injury on athletic performance. |

There is currently no universally accepted self-reported outcome measure of athlete performance. |

The Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre overuse injury questionnaire has potential for development for use across different sports. |

1 Background

Athlete-reported measures of health, wellbeing and performance can add meaningful information to that obtained from traditional physiological and biochemical performance measures [1, 2]. Research which includes the athlete’s perspective has contributed to a greater understanding of development and performance along with issues pertaining to athlete welfare and wellbeing [1, 3].

Validity and reliability are key characteristics of self-reported outcome measures [4] and questionnaires with evidence of validity and reliability in a general population or even a younger active population have been previously used in the sporting setting. However their length, narrow focus or lack of specificity to the athlete population has led to widespread use of study-specific questionnaires within sports medicine. While this reflects an attempt to reduce the burden on the athlete and increase the relevance, it may compromise validity and reliability [2, 5].

The scores obtained from these self-reported measures should allow valid inferences to be made including hypothesis-testing, therefore they should be assessed for validity in the particular population of interest. Evidence of validity accumulates over time from multiple studies [4, 5], therefore there is a need for consensus regarding the methods used to record and measure health-related incidents and their consequences for athletes [4–6]. Used together these values describe change that can be distinguished from measurement error and is important to athletes [6].

Athletes are different from the general population [7, 8]. They have higher levels of physical function, psychological function and perceived health. Physical activity is often their main employment, therefore the morbidity consequences of injury and illness tend to be high [9]. Athletes may not manifest symptoms during activities of daily living, and existing outcomes measures may not detect problems resulting from the demands of their training and competition [10], thus development of outcome measures that are specific to high performance sport could be important [9, 11–13].

The negative consequences of health problems include impairment, activity limitation and participation restrictions [11, 12]. Information regarding the prevalence and impact of health-related incidents is important to establish the burden of health problems and inform appropriate preventive and health promotion strategies [13–17]. However, athletes may not always seek medical care or present as patients, therefore patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) may not be sufficient to capture all available information [9, 11, 18–21]. Additional barriers to the use of self-reported outcome measures include time to complete and lack of accessibility [2, 22].

Measures that are easy to understand, administer, score and interpret are more likely to be useful to all stakeholders in sport, including athletes, clinicians, researchers, support staff, funding bodies and policy makers [9]. We aimed to review the evidence to determine which athlete-reported outcomes have been used to evaluate the impact of health problems on performance in sport. A secondary objective was to evaluate eligible outcome measures for evidence of validity and potential for future research.

2 Methods

In order to address the first objective we conducted a systematic review to answer the focused question: “Which athlete-reported outcome measures of performance have been used to measure the impact of injury and illness on performance in sport?”

Studies were included if they met the following eligibility criteria: (1) participants were currently or had been competing at an elite level as able-bodied athletes; elite level was defined as competitive at Olympic, international, national or professional level [7], (2) any outcome measure of performance, assessed in relation to illness, injury or a related intervention, was reported by the athlete including functional and generic patient-reported outcome measures (PROMS), athlete diaries, interviews and patient satisfaction surveys; (3) the study was published in English. Studies were excluded from the review based on the following criteria: (1) participants were under the age of 16 years; (2) participants were competing at a recreational level; (3) the study was undertaken with a heterogeneous sample (e.g. elite and non-elite, able-bodied and disabled, under and over age 16 years) without reporting groups separately.

2.1 Search Methods for Identification of Studies

2.1.1 Electronic Searches

The databases of MEDLINE (Ovid version), EMBASE, CINAHL Plus, SPORTDiscus with Full Text, and Cochrane library were searched to 26 January 2016. A sensitive search strategy was devised initially in MEDLINE including the following search terms: self-report * athlete * patient reported outcome measure * and used in subsequent searches. An overview of the search strategy is available on request.

2.1.2 Searching Other Resources

The reference lists of included studies were checked for other papers that might be suitable for inclusion.

2.2 Data Extraction

Titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility by one of the authors (JG). The full text of all potentially eligible studies was assessed for inclusion by two authors in duplicate and independently (JG and RGS), resolving disagreements by discussion. Where resolution could not be achieved, a third author, experienced in conducting systematic reviews, arbitrated (IN). For included studies, data were extracted using a specially designed form (piloted before use) also in duplicate and independently by two reviewers. Where information in a paper was unclear, the corresponding author was contacted for clarification. Data extraction related to type of study, setting where the study took place, sport, population, injury or illness regardless of need for medical attention and details of the outcome measure.

2.3 Quality Assessment

In order to address our second objective, validity of development of outcome measures was assessed. Aspects of validity were evaluated using a pre-defined checklist based on the taxonomy and criteria proposed by Terwee et al. [23, 24] for evaluation of measurement properties of health status questionnaires.

2.3.1 Validity

There are many types of validity evidence [6] including face validity (the instrument actually measures the intended construct), content and construct validity. We considered evidence for content validity to include a clear description of the measurement aim, the target population, the concepts being measured and item selection. In addition the target population should have been involved in item selection. Evidence for internal consistency required factor analysis to be applied, with a Cronbach’s alpha value between 0.7 and 0.95. Ideally there should be at least 50 participants and minimal floor or ceiling effects [21].

Evidence for construct validity included reporting of values to show convergent validity (agreement in scores from other outcome measures which aim to assess similar constructs) and/or divergent validity (low correlation with scores from outcome measures which assess different constructs). Correlation coefficients such as the Spearman rho or Pearson r are most commonly reported in construct validation studies [6]. There should be at least 50 participants and at least 75% of the results should support a previously defined hypothesis [21].

2.3.2 Reproducibility (Agreement and Reliability)

The outcome measure scores should reflect changes where real change has occurred rather than changes due to measurement error. Evidence for agreement included at least 50 participants and the standard error of measurement (SEM) to be reported along with smallest detectable change (SDC) and minimal important change (MIC) or convincing arguments that agreement is acceptable. Evidence for reliability required at least 50 participants and an intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) of at least 0.7 to be reported [21].

2.3.3 Responsiveness (Longitudinal Validity)

Evidence for the outcome measurement instrument to detect clinically important change over time included correlation with scores from other outcome measures of the same construct. Interpretability was assessed from evidence that a (change in) score was clinically meaningful along with means and standard deviations (SDs) of scores of reference populations and participant subgroups. In addition an MIC should be defined [21].

2.4 Data Synthesis and Reporting

In keeping with the aims of the review, findings from eligible studies were combined narratively using tables of evidence. The characteristics of the outcomes were used to synthesise results as well as validity outcomes. Reporting of the review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guideline [25].

3 Results

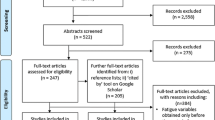

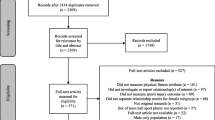

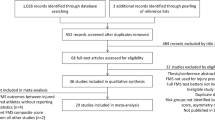

The adopted search strategies yielded 6536 results. After removal of duplicates and titles clearly not relevant to the research question, 1358 articles were further screened by title and abstract for consideration in full text screening. The full text of 159 articles was assessed against eligibility criteria and 21 articles were finally included [26–46]. Agreement on article inclusion was high (0.8). Reasons for exclusion of full text studies are given in Fig. 1.

3.1 Characteristics of Included Studies

The studies represented a range of countries, with the USA being the most frequent. Seven categories of health problems including hip and groin, knee, shoulder, lower back, eyes, oral health, overuse injuries and illness were represented across 34 different sports (Table 1). Ten of the 20 outcome measures were used in evaluations of medical interventions [31, 32, 34, 36–38, 41, 43–45].

3.2 Characteristics of the Athlete-Reported Outcome Measures

Athlete-reported outcome measures of performance included return to play, time to return to training/competition, level of competition, perception of performance compared to pre-injury, participation limitation, reduction in volume of training and impact on performance. A summary of the athlete-reported outcomes identified by the search is presented in Table 2.

3.3 Evaluation of Athlete-Reported Outcome Measures Used in Health Surveillance

Nine different athlete-reported outcome measures were used in ten observational (epidemiological or surveillance) studies [26, 27, 29, 30, 33, 35, 39, 40, 42, 46]. However, most were designed for use in individual studies without reference to evidence of validity. Self-reported information was used in one qualitative investigation of rugby players’ experiences following anterior cruciate ligament injury and repair, conducted over a period of rehabilitation and return to competition [28]. Quality criteria based on a pre-defined checklist [23, 24] were applied to the four questionnaires where the study had included a reference to evidence of validity of the outcome measure (Table 3).

3.4 Athlete- Versus Patient-Reported Outcomes to Evaluate Medical Interventions

None of the athlete-reported outcomes of performance used in evaluation of medical interventions cited assessment of validity; seven were used in conjunction with PROMs, not all of which cited validity in a sporting population (Table 2). However, three of the functional PROMs—International Hip Outcome Tool (iHOT-12), Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS) and Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment-Patellar Tendinopathy (VISA-P)—identified by this review have evidence of validity in a younger active population [48–50]. The three generic PROMs used in the studies—Short Form (12) Health survey (SF-12), Short Form (36) Health Survey (SF-36) and EuroQol (EQ-5D) Health Questionnaire—have been reviewed by another author and found to have limited validity in a sport and recreation population [9]. The Hip Sports Activity Scale (HSAS) used to identify level of sporting activity (Table 4) has evidence of validity in young patients with hip disease [47].

4 Discussion

Our key finding is that most athlete-reported outcome measures of performance to assess the impact of illness and injury on performance in sport identified in this review were developed for use in individual studies. There can never be a single study which validates an outcome measure; however, evidence of validity and reliability of the inferences drawn from the data accumulates over time with use in multiple studies, thereby allowing meaningful comparison across studies. One oral health self-reported measure of impact on performance was used in Olympic athletes and professional footballers, but evidence of its validity has been assessed in a general population only. Functional PROMs such as i-HOT12, HAGOS and VISA-P, developed using the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) guidelines, demonstrate validity in young, active populations but not specifically in elite sport groups (Table 4). The HSAS self-reported measure of athletic capability has evidence of validity and reliability and could be a useful model for a tool to report the level of competition of athletes in research studies. Although rich in qualitative information, athlete interviews require a substantial time commitment from both the athlete and the researcher, as does the use of multiple PROMs. Consistent use of outcome measures with evidence of validity and reliability could help to quantify the burden of injury and illness and relative risk in athletes across different sporting activities. Researchers should aim to identify and use outcome measures with evidence of validity in the target group in which they are to be used. Three athlete-reported outcome measures of impact on performance demonstrate validity in a high performance athletic population—the OSTRC overuse injury questionnaire, the OSTRC questionnaire on health problems and the KJOC shoulder and elbow questionnaire; however, the KJOC questionnaire is specific to overhead throwing athletes. All are short and straightforward to complete and measure impact on performance in terms of athlete-reported pain/symptoms, participation, volume and quality of training/competition.

4.1 Strengths and Limitations of the Included Evidence

There are challenges to drawing robust conclusions from the included evidence. In general, the data regarding the outcome measures were drawn from their use in single studies, although one measure of the impact of oral health on performance was used in two separate studies. Few questionnaires reported development using a structured approach and involvement of the target population, limiting their validity.

4.2 Strengths and Limitations of the Review

4.2.1 Eligibility Criteria; Performance Level

In order to limit the review we made a decision to limit the participants in the studies to high performance, able-bodied athletes. This focus resulted in several studies being excluded because the studies included participants with disabilities, participants under the age of 16 years or recreational sports people who could not be separated out from the highest level athletes.

4.2.2 Performance Versus Functional Outcomes

Return to play is dependent on a number of factors, most of which are outside an athlete’s control. Included studies had to demonstrate that a self-reported outcome measure was used to evaluate the impact upon performance in elite athletes. This resulted in exclusion of studies which included heterogeneous samples and reported on the development of functional outcome measures using the COSMIN criteria, such as the Functional Assessment Scale for Acute Hamstring Injuries (FASH) [52] and Victorian Institute of Sport Assessment—Achilles Tendinopathy (VISA-A)

4.2.3 Risk of Bias and Quality Assurance

We attempted to minimise bias by developing the protocol a priori and employing duplicate full-text screening and data abstraction. However, initial eligibility assessment of titles and abstracts was carried out by one researcher (JG), which might have introduced bias in study selection.

4.2.4 Comparison with Other Reviews

This review supports the finding of related reviews. One systematic review of PROMs used to assess Achilles tendon rupture management [53] applied COSMIN criteria to 17 region-specific and condition-specific outcome measures; the authors found only four were presented in articles that referenced development and/or validation of that outcome measure and of these only one was developed using recognised methodology for outcome measure development. A systematic review of instruments used to assess outcomes of sport and active recreation injury [9] listed seven different health status and health-related quality-of-life measures, five different functional outcome measures and three physical activity measures; the authors stated that none have been specifically or region designed to measure injury outcomes in a general sport and active recreation population. One recent study of low back pain in international level rowers [54] recommended using the OSTRC overuse injury questionnaire, demonstrating its potential for use across all sports.

5 Conclusion

Within the limits of this review there is currently no universally accepted athlete-reported outcome measure of the impact of injury/illness on performance in sport. Most questionnaires were designed for individual studies and evidence to support their validity, reliability and responsiveness has not been reported. The KJOC shoulder and elbow questionnaire has evidence to support its validity, reliability and responsiveness but is specific to professional baseball players. Consistent use of self-reported outcome measures with evidence of validity, reliability and responsiveness would lead to more reliable and comparable evidence. Despite some limitations, as a potential tool to measure athlete-reported impact on performance across a variety of sports, the OSTRC questionnaire on overuse injuries forms a model that could be adapted to evaluate the impact of any pre-defined health problem on athletic performance. The addition of items related to impact on quality of life could add value in terms of understanding the negative consequences of injury and illness in sport.

References

Saw AE, Main LC, Gastin PB. Monitoring the athlete training response: subjective self-reported measures trump commonly used objective measures: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2015. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094758.

Saw AE, Main LC, Gastin PB. Monitoring athletes through self-report: factors influencing implementation. J Sports Sci Med. 2015;14(1):137–46.

Weissensteiner JR. The importance of listening: engaging and incorporating the athlete’s voice in theory and practice. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(13):839–40. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094601.

Kelly PA, O’Malley KJ, Kallen MA, et al. Integrating validity theory with use of measurement instruments in clinical settings. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(5 Pt 2):1605–19. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00445.x.

Messick S. Validity of psychological assessment: validation of inferences from persons’ responses and performances as scientific inquiry into score meaning. Am Psychol. 1995;50(9):741–9. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.50.9.741.

Davidson M, Keating J. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): how should I interpret reports of measurement properties? A practical guide for clinicians and researchers who are not biostatisticians. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(9):792–6. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2012-091704.

Swann C, Moran A, Piggott D. Defining elite athletes: Issues in the study of expert performance in sport psychology. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2015;16:Part 1:3–14. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.07.004.

De Pauw K, Roelands B, Cheung SS, et al. Guidelines to classify subject groups in sport-science research. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2013;8(2):111–22.

Andrew NE, Gabbe BJ, Wolfe R, et al. Evaluation of instruments for measuring the burden of sport and active recreation injury. Sports Med. 2010;40(2):141–61.

Alberta FG, ElAttrache NS, Bissell S, et al. The development and validation of a functional assessment tool for the upper extremity in the overhead athlete. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(5):903–11. doi:10.1177/0363546509355642.

Ljungqvist A, Jenoure P, Engebretsen L, et al. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) Consensus Statement on periodic health evaluation of elite athletes March 2009. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(9):631–43. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2009.064394.

Matheson GO, Klugl M, Engebretsen L, et al. Prevention and management of non-communicable disease: the IOC consensus statement, Lausanne 2013. Sports Med. 2013;43(11):1075–88. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0104-3.

Code médical du Mouvement olympique—Olympic Movement Medical Code État en vigueur au 1er octobre 2009—In force as from 1 October 2009. <Olympic_Movement_Medical_Code_eng.pdf>.

Finch C. A new framework for research leading to sports injury prevention. J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9(1–2):3–9. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2006.02.009.

Needleman I, Ashley P, Fine P, et al. Oral health and elite sport performance. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(1):3–6. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-093804.

Engebretsen L, Soligard T, Steffen K, et al. Sports injuries and illnesses during the London Summer Olympic Games 2012. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(7):407–14. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092380.

Steffen K, Soligard T, Engebretsen L. Health protection of the Olympic athlete. BJSM online. 2012;46(7):466–70. doi:10.1136/466bjsports-2012-091168.

Ashley P, Di Iorio A, Cole E, et al. Oral health of elite athletes and association with performance: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(1):14–9. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-093617.

Davis JC, Bryan S. Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) have arrived in sports and exercise medicine: why do they matter? Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(24):1545–6. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-093707.

Dijkstra HP, Pollock N, Chakraverty R, et al. Managing the health of the elite athlete: a new integrated performance health management and coaching model. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(7):523–31. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-093222.

Clarsen B, Bahr R. Matching the choice of injury/illness definition to study setting, purpose and design: one size does not fit all! BJSM online. 2014;48(7):510–2. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-093297.

Valier ARS, Jennings AL, Parsons JT, et al. Benefits of and barriers to using patient-rated outcome measures in athletic training. J Athl Train. 2014;49(5):674–83.

Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, et al. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: an international Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(4):539–49. doi:10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8.

Terwee CB, Bot SDM, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(1):34–42. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–12. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005.

Azodo CC, Osazuwa O. Dental conditions among competitive university athletes in Nigeria. Odontostomatol Trop. 2013;36(141):34–42.

Bjorneboe J, Florenes TW, Bahr R, et al. Injury surveillance in male professional football; is medical staff reporting complete and accurate? Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21(5):713–20. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01085.x.

Carson F, Polman R. Experiences of professional rugby union players returning to competition following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Phys Ther Sport. 2012;13(1):35–40. doi:10.1016/j.ptsp.2010.10.007.

Clarsen B, Myklebust G, Bahr R. Development and validation of a new method for the registration of overuse injuries in sports injury epidemiology: the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre (OSTRC) overuse injury questionnaire. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(8):495–502. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2012-091524.

Clarsen B, Ronsen O, Myklebust G, et al. The Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center questionnaire on health problems: a new approach to prospective monitoring of illness and injury in elite athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(9):754–60. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2012-092087.

Cohen DB, Coleman S, Drakos MC, et al. Outcomes of isolated type II SLAP lesions treated with arthroscopic fixation using a bioabsorbable tack. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(2):136–42.

Dugas JR, Bilotta J, Watts CD, et al. Ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction with gracilis tendon in athletes with intraligamentous bony excision: technique and results. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(7):1578–82. doi:10.1177/0363546512446927.

Franz JO, McCulloch PC, Kneip CJ, et al. The utility of the KJOC score in professional baseball in the United States. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(9):2167–73. doi:10.1177/0363546513495177.

Mann CD, Sutton CD, Garcea G, et al. The inguinal release procedure for groin pain: initial experience in 73 sportsmen/women. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(8):579–83. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.053132.

Matthews A, Pyne D, Saunders P, et al. A self-reported questionnaire for quantifying illness symptoms in elite athletes. Open Access J Sports Med. 2010;1:15–22.

McAllister DR, Tsai AM, Dragoo JL, et al. Knee function after anterior cruciate ligament injury in elite collegiate athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31(4):560–3.

Muschaweck U, Berger L. Minimal Repair technique of sportsmen’s groin: an innovative open-suture repair to treat chronic inguinal pain. Hernia. 2010;14(1):27–33. doi:10.1007/s10029-009-0614-y.

Naal FD, Miozzari HH, Wyss TF, et al. Surgical hip dislocation for the treatment of femoroacetabular impingement in high-level athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(3):544–50. doi:10.1177/0363546510387263.

Needleman I, Ashley P, Meehan L, et al. Poor oral health including active caries in 187 UK professional male football players: clinical dental examination performed by dentists. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(1):41–4. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094953.

Needleman I, Ashley P, Petrie A, et al. Oral health and impact on performance of athletes participating in the London 2012 Olympic Games: a cross-sectional study. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(16):1054–8. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2013-092891.

Nho SJ, Magennis EM, Singh CK, et al. Outcomes after the arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement in a mixed group of high-level athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:14S–9S.

Nilstad A, Bahr R, Andersen TE. Text messaging as a new method for injury registration in sports: a methodological study in elite female football. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;24(1):243–9. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2012.01471.x.

Pascarella A, Alam M, Pascarella F, et al. Arthroscopic management of chronic patellar tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(9):1975–83.

Philippon MJ, Weiss DR, Kuppersmith DA, et al. Arthroscopic labral repair and treatment of femoroacetabular impingement in professional hockey players. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(1):99–104.

Sansone M, Ahlden M, Jonasson P, et al. Can hip impingement be mistaken for tendon pain in the groin? A long-term follow-up of tenotomy for groin pain in athletes. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2014;22(4):786–92. doi:10.1007/s00167-013-2738-y.

Waicus KM, Smith BW. Eye injuries in women’s lacrosse players. Clin J Sport Med. 2002;12(1):24–9.

Naal FD, Miozzari HH, Kelly BT, et al. The Hip Sports Activity Scale (HSAS) for patients with femoroacetabular impingement. Hip Int. 2013;23(2):204–11. doi:10.5301/hipint.5000006.

Hernandez-Sanchez S, Hidalgo MD, Gomez A. Responsiveness of the VISA-P scale for patellar tendinopathy in athletes. BJSM Online. 2014;48(6):453–7. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2012-091163.

Jonasson P, Baranto A, Karlsson J, et al. A standardised outcome measure of pain, symptoms and physical function in patients with hip and groin disability due to femoro-acetabular impingement: cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the international Hip Outcome Tool (iHOT12) in Swedish. Knee Surg Sport Tr A. 2014;22(4):826–34. doi:10.1007/s00167-013-2710-x.

Thorborg K, Holmich P, Christensen R, et al. The Copenhagen Hip and Groin Outcome Score (HAGOS): development and validation according to the COSMIN checklist. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(6):478–91. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2010.080937.

Locker D, Quinonez C. To what extent do oral disorders compromise the quality of life? Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2011;39(1):3–11. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.2010.00597.x.

Malliaropoulos N, Korakakis V, Christodoulou D, et al. Development and validation of a questionnaire (FASH–Functional Assessment Scale for Acute Hamstring Injuries): to measure the severity and impact of symptoms on function and sports ability in patients with acute hamstring injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(22):1607–12. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-094021.

Kearney RS, Achten J, Lamb SE, et al. A systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures used to assess Achilles tendon rupture management: what’s being used and should we be using it? Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(16):1102–9. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2011-090497.

Newlands C, Reid D, Parmar P. The prevalence, incidence and severity of low back pain among international-level rowers. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(14):951–6. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-093889.

Author contributions

Ian Needleman conceived the study. Robbie Lumsden assisted with formulating the systematic search strategy. Julie Gallagher and Ruben Garcia Sanchez were responsible for duplicate screening and data extraction. Julie Gallagher prepared the first draft of the study protocol and the manuscript and was chiefly responsible for the conduct of the review. Ian Needleman, Paul Ashley and Julie Gallagher contributed to the final draft of the protocol and manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The research project that resulted in this review was funded by an investigator-led grant from GlaxoSmithKline (Award Number 157871) and an Impact Award from University College London.

Conflict of interest

Julie Gallagher, Paul Ashley, Ruben Garcia Sanchez, Robbie Lumsden and Ian Needleman declare that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this review.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gallagher, J., Needleman, I., Ashley, P. et al. Self-Reported Outcome Measures of the Impact of Injury and Illness on Athlete Performance: A Systematic Review. Sports Med 47, 1335–1348 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0651-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0651-5