Abstract

Background

While bereavement is associated with increased mortality, it is unclear how bereaved families utilize the healthcare system after the death of their loved ones.

Objective

The aim of this study was to examine the association between bereavement and healthcare expenditures for surviving spouses.

Methods

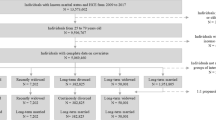

We used data from the Health and Retirement Study, a nationally representative cohort study of older adults linked to Medicare claims. We determined a spouse’s total Medicare expenditures 2 years before and after their partner’s death across six biennial interview waves. Using coarsened exact matching, we created a comparison group of non-bereaved dyads. Costs were wage index- and inflation-adjusted to 2017 dollars. We used generalized linear models and difference-in-differences (DID) analysis to calculate the average marginal effects of bereavement on Medicare spending by gender. We also examined subgroup differences based on caregiver status, cause of death, and length of terminal illness.

Results

Our sample consisted of 941 bereaved dyads and a comparison group of 8899 matched dyads. Surviving female spouses (68% of the sample) had a $3500 increase in spending 2 years after death (p < 0.05). Using DID analyses, bereavement was associated with a $625 quarterly increase in Medicare expenditures over 2 years for women. There was no significant increase in post-death spending for male bereaved surviving spouses. Results were consistent for spouses who survived at least 2 years after the death of their spouse (70% of the sample)

Conclusions

Bereavement is associated with increased healthcare spending for women regardless of their caregiving status, the cause of death, or length of terminal illness. Further study is required to examine why men and women have different patterns of healthcare spending relative to the death of their spouses.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ornstein KA, et al. A national profile of end-of-life caregiving in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(7):1184–92.

Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(2):250–67.

Buyck JF, et al. Informal caregiving and the risk for coronary heart disease: the Whitehall II Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(10):1316–23.

Ho SC, et al. Impact of caregiving on health and quality of life: a comparative population-based study of caregivers for elderly persons and noncaregivers. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(8):873–9.

Son J, et al. The caregiver stress process and health outcomes. J Aging Health. 2007;19(6):871–87.

Reeves KW, Bacon K, Fredman L. Caregiving associated with selected cancer risk behaviors and screening utilization among women: cross-sectional results of the 2009 BRFSS. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:685.

Elwert F, Christakis NA. The effect of widowhood on mortality by the causes of death of both spouses. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(11):2092–8.

Parkes CM, Benjamin B, Fitzgerald RG. Broken heart: a statistical study of increased mortality among widowers. Br Med J. 1969;1(5646):740–3.

Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet. 2007;370(9603):1960–73.

Sullivan AR, Fenelon A. Patterns of widowhood mortality. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69(1):53–62.

Vable AM, et al. Does the “widowhood effect” precede spousal bereavement? Results from a nationally representative sample of older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(3):283–92.

McHorney CA, Mor V. Predictors of bereavement depression and its health services consequences. Med Care. 1988;26(9):882–93.

Moore MJ, Zhu CW, Clipp EC. Informal costs of dementia care: estimates from the National Longitudinal Caregiver Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56(4):S219–28.

Schulz R, Cook T, Hunt G. AD caregivers: healthcare utilizations and cost over 18 months. Gerontologist. 2011;51(S2):568.

Grasel E. When home care ends: changes in the physical health of informal caregivers caring for dementia patients: a longitudinal study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(5):843–9.

Guldin MB, et al. Healthcare utilization of bereaved relatives of patients who died from cancer. A national population-based study. Psychooncology. 2013;22(5):1152–8.

Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Rosenheck RA. Preliminary explorations of the harmful interactive effects of widowhood and marital harmony on health, health service use, and health care costs. Gerontologist. 2000;40(3):349–57.

Rolden HJ, van Bodegom D, Westendorp RG. Changes in health care expenditure after the loss of a spouse: data on 6,487 older widows and widowers in the Netherlands. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e115478.

Stephen AI, et al. The economic cost of bereavement in Scotland. Death Stud. 2015;39(1–5):151–7.

Shah SM, et al. Impact of partner bereavement on quality of cardiovascular disease management. Circulation. 2013;128(25):2745–53.

Carey IM, et al. Increased risk of acute cardiovascular events after partner bereavement: a matched cohort study. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):598–605.

Ornstein KA, et al. Downstream effects of end-of-life care for older adults with serious illness on health care utilization of family caregivers. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(9):736–7.

Hurd MD, et al. Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(14):1326–34.

van den Berg B, Brouwer WB, Koopmanschap MA. Economic valuation of informal care. An overview of methods and applications. Eur J Health Econ. 2004;5(1):36–45.

Family Caregiver Alliance. Caregiving. 2009 [cited 19 Sep 2013]. Available at: http://www.caregiver.org/caregiver/jsp/content_node.jsp?nodeid=2313.

Health and Retirement Study. 2013 [cited 17 Sep 2013]. Available at: http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/.

United States Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index. 2018 [cited 15 Jul 2018]. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/cpi/.

MEDPAC. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. [cited 15 Jul 2018]. Available at: http://www.medpac.gov/.

Wennberg JE, Cooper M. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. 2013 [cited 17 Sep 2013]. Available at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/.

Iacus CM, King G, Porro G. Causal inference without balance checking: coarsened exact matching. Polit Anal. 2011;20:1–24.

Garrido MM, et al. Methods for constructing and assessing propensity scores. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(5):1701–20.

Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28(25):3083–107.

Deb P, Norton EC. Modeling health care expenditures and use. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39:489–505.

Katz SJ, Kabeto M, Langa KM. Gender disparities in the receipt of home care for elderly people with disability in the United States. JAMA. 2000;284(23):3022–7.

Davydow DS, et al. Depressive symptoms in spouses of older patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(8):2335–41.

Ryan AM, Burgess JF Jr, Dimick JB. Why we should not be indifferent to specification choices for difference-in-differences. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(4):1211–35.

Zhang AY, Zyzanski SJ, Siminoff LA. Differential patient-caregiver opinions of treatment and care for advanced lung cancer patients. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(8):1155–8.

Morgan T, et al. Gender and family caregiving at the end-of-life in the context of old age: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2016;30(7):616–24.

Washington KT, et al. Gender differences in caregiving at end of life: implications for hospice teams. J Palliat Med. 2015;18(12):1048–53.

Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: an updated meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61(1):P33–45.

Williams LA, et al. ‘Because it’s the wife who has to look after the man’: a descriptive qualitative study of older women and the intersection of gender and the provision of family caregiving at the end of life. Palliat Med. 2017;31(3):223–30.

DiGiacomo M, et al. Transitioning from caregiving to widowhood. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2013;46(6):817–25.

Burkhauser RV, et al. Until death do us part: an analysis of the economic well-being of widows in four countries. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2005;60(5):S238–46.

DiGiacomo M, et al. The business of death: a qualitative study of financial concerns of widowed older women. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15:36.

Moon JR, et al. Widowhood and mortality: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23465.

Dunlay SM, et al. Patient and spousal health and outcomes in heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10(10) (pii: e004088).

Caregiving in the U.S. 2015. National Alliance for Caregiving and the AARP Public Policy Institute; 2015.

Calasanti T, King N. Taking ‘women’s work’ ‘like a man’: husbands’ experiences of care work. Gerontologist. 2007;47(4):516–27.

Calasanti T. Feminist gerontology and old men. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2004;59(6):S305–14.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KO and AK developed the research question, and KO, MG, O-KR and EB-L developed the research methodology and conducted the analyses. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Katherine Ornstein, Melissa Garrido, Albert Siu, Evan Bollens-Lund, Omari-Khalid Rahman, and Amy Kelley have no financial conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding

The HRS is funded by the National Institute of Aging (NIA) [NIA U01 AG009740] and the Social Security Administration. The study investigators were supported by the National Institute on Aging (Grant Numbers K01AG047923 [Dr. Ornstein] and R01AG054540 [Dr. Kelley]), and VA HSR&D 16-140 (Dr. Garrido). The funding sources had no role in the design, conduct, and analysis of this study or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ornstein, K.A., Garrido, M.M., Siu, A.L. et al. An Examination of Downstream Effects of Bereavement on Healthcare Utilization for Surviving Spouses in a National Sample of Older Adults. PharmacoEconomics 37, 585–596 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-019-00787-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-019-00787-4