Abstract

Background

Since the introduction of the five-level version of the EQ-5D (5L), many studies have comparatively investigated the measurement properties of the original three-level version (3L) with the 5L version.

Objective

The aim of this study was to consolidate the available evidence on the performance of both instruments.

Methods

A systematic literature search of studies in the English and German languages was conducted (2007–January 2018) using the PubMed, EMBASE, and PsycINFO (EBSCO) databases, as well as the EuroQol Research Foundation website. Data were extracted and assessed on missing values, distributional properties, informativity indices (Shannon’s H′ and J′), inconsistencies, responsiveness, and test–retest reliability.

Results

Twenty-four studies were included in the review. Missing values and floor effects (percentage reporting the worst health state) were found to be negligible for both 3L and 5L (< 5%). From 18 studies, inconsistencies ranged from 0 to 10.6%, although they were generally well below 5%, with 9 studies reporting the most inconsistencies for Usual Activities (mean percentage 4.1%). Shannon’s indices were always higher for 5L than for 3L, and all but three studies reported lower ceiling effects (‘11111’) for 5L than for 3L. There is mixed and insufficient evidence on responsiveness and test–retest reliability, although results on index values showed better performance for 5L on test–retest reliability.

Conclusion

Overall, studies showed similar or better measurement properties of the 5L compared with the 3L, and evidence indicated moderately better distributional parameters and substantial improvement in informativity for the 5L compared with the 3L. Insufficient evidence on responsiveness and test–retest reliability implies further research is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

This review supports the use of both the 3L and the 5L in a broad range of patients, populations and countries. |

The 5L showed better or at least similar measurement properties when compared to the 3L. |

Evidence on responsiveness is inconclusive and requires further research. |

1 Introduction

The EQ-5D is one of the most widely used instruments to describe and value health [1, 2]. It is a generic, self-completion questionnaire consisting of two parts: a 5-item descriptive system and a thermometer-like visual analogue scale ranging from 0 to 100 (the EQ-VAS). It comprises five items, each describing one dimension [Mobility (MO), Self-Care (SC), Usual Activities (UA), Pain/Discomfort (PD), and Anxiety/Depression (AD)]. The original questionnaire, introduced in 1990 [3], allows respondents to choose between three options; level 1, representing no problems; level 2, reflecting small or moderate problems; and level 3, indicating extreme problems (or ‘unable to’). Self-ratings on the three levels in the five dimensions (items) can be summarized to produce 243 health states, also known as a health profile. Health profiles can be assigned index values derived from econometric techniques to elicit societal preference weights. These index values can then be used in economic evaluation of health programs [1, 4].

The EQ-5D was conceptualized to capture deviations from ‘normal’ health, thereby focusing on self-reported health and health-related quality-of-life problems while not attempting to capture aspects beyond health. Internationally, it is currently one of the most widely used preference-based quality-of-life questionnaires. A large body of literature demonstrates that the instrument is valid and reliable [5,6,7]. However, although the EQ-5D was developed to supplement other instruments, this simple and short measure has been increasingly used as a ‘stand-alone tool’ [8, 9]. The increase in use of the EQ-5D in the field of health technology assessment raises concerns about methodological measurement issues [10]. The first is the EQ-5D’s ceiling effect, or a high proportion of participants reporting ‘no problems’ on one or all dimensions [11,12,13]. Second, some studies found the EQ-5D to be less responsive to changes in health compared with other preference-based measures [e.g. Health Utility Index (HUI), Short-Form 6-Dimension (SF-6D), Quality of Well-Being Scale–Self Administered (QWB-SA)] [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. To address these concerns, paired with the inherent aspiration of the ever-expanding research community to continually improve the instrument, a new version of the EQ-5D was developed by the EuroQol group [22,23,24]. The new version expanded the response choices from three to five levels and changed the wording of some of the response categories (Table 1). The new version is called the EQ-5D-5L [25], and can describe 3125 (= 55) health conditions.

Since introducing the EQ-5D-5L in 2011, many studies have comparatively investigated the measurement properties of the original EQ-5D (now interchangeably referred to as EQ-5D-3L or 3L) and the newer EQ-5D-5L (now interchangeably referred to as EQ-5D-5L or 5L). In this review we summarize the consolidated findings from these studies.

2 Methods

2.1 Data Sources, Search Strategy, Study Selection, and Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We conducted a systematic literature search to identify all studies in the English and German languages comparing the 3L and the 5L published between January 2007 and May 2016 using the following keywords: ‘EQ-5D-5L’, ‘EQ-5D 5L’, ‘EuroQol AND 5L’, ‘EuroQoL AND 5 level’. Electronic searches were performed in the PubMed, EMBASE, and PsycINFO (EBSCO) databases, in addition to the EuroQol Research Foundation website, for relevant publications. The inclusion criteria were primary study or conference paper comparing the final versions of the 3L and the 5L(studies using experimental versions were excluded). Articles were further excluded if they did not assess the EQ-5D, were of another publication type, it was not an empirical study in adults, were not in English or German, or were not available in full text. The review was updated during the process of manuscript revision using the same search algorithms, and inclusion and exclusion/eligibility criteria as detailed above. The search was conducted in articles published between May 2016 and January 2018. The process of study selection is shown in Fig. 1.

2.2 Screening and Data Extraction

Two researchers independently reviewed the title and abstract of all identified studies, while a third reviewer (TK or MFJ) was consulted in case of variance. After removing duplicates, full-text articles were reviewed by one reviewer (IB) and doubled-checked by the second reviewer (YSF) for missing extractions. For cases of papers that used the same data, those with more information on the indicators of interest were always included. When publications addressed different information based on the same data, both papers were included. For each article, the following information was extracted: authors, title and year of publication, sample characteristics (e.g. sample size, percentage of females, mean age), country, outcome measures used, aims of the study, study design, and parameters describing relevant measure properties. The measurement properties were distributional properties, informativity, inconsistencies, responsiveness and test–retest reliability. All of these properties were assessed in terms of results related to the descriptive systems of the 3L and 5L. For responsiveness and test–retest reliability, results on index values were also included.

2.3 Quality Assessment of Studies

The quality of the full-text articles included for review was assessed using a 9-item critical appraisal tool (see the electronic supplementary material [ESM]). The items were defined based on the ‘Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies’ from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) [26], and contained (1) objective/research questions; (2) study population; (3) groups recruited/eligibility criteria; (4) study design; (5) sample size; (6) response rate; (7) data collection; (8) outcome parameter; and (9) statistical tests/analysis. Study quality was assessed as excellent, good, fair or poor, with the corresponding number of criteria fulfilled being 8–9, 5–7, 3–4 or 0–2.

2.4 Distributional Properties

We compared the 3L and 5L on their classical distribution characteristics, such as the number and proportion of missing values, the number and percentage reporting the best (ceiling; ‘no problems’) and worst (floor) level of health state in each dimension and across all dimensions (e.g. ‘11111’ and ‘33333’ for the 3L or ‘55555’ for the 5L, respectively). The results are presented as ranges of percentages or numbers of studies in which the 5L performed equal to, worse than, or better than the 3L (e.g. How often did more than 15% [as suggested by Terwee et al. [27]] of the study sample report ‘no problems’ when using the 5L compared with the 3L?) We used random effects logit transformation to calculate pooled proportions from single proportions using R’s ‘meta’ package specifically for proportion reporting ‘no problems’ across all dimensions (‘11111’). Pooled proportions give an idea of the overall ceiling effect when taking into account the sample sizes across included studies.

2.5 Informativity

Shannon’s index is based on information theory and allows an assessment on the informational and discriminatory power of each descriptive system.

According to Shannon’s indices, an item is most efficiently used when all responses are evenly distributed across all response options [28], with a higher index indicating more information captured by the instrument. While H′ represents the extent to which the information is evenly distributed across all categories, Shannon’s J′ additionally takes into account the number of response options or descriptive categories of the measurement system. J′ can take values between 0 and 1, with a J′ of 0 representing that all responses are concentrated in one response level (most uneven distribution; worst discriminatory power) and 1 representing that all response levels are evenly distributed (even distribution; best discriminatory power). There is no straightforward interpretation for H′. Since H′max depends on the number of levels, within our context H′ can take values between 0 (no informational richness/discriminatory power) and 1.58 (log2L, with the number of levels L = 3) for the 3L and 2.32 (log2L, with L = 5) for the 5L (which corresponds to the highest informational richness/discriminatory power).

Within this review, H′ and J′ were extracted from the studies or calculated using these formulas, where p i is the proportion of responses in the ith response option:

Both indices are reported for each EQ-5D dimension. We aggregated the mean information gain by the 5L, which was calculated through dividing Shannon’s H′ of the 5L by Shannon’s H′ of the 3L (H′5L/H′3L) and Shannon’s J′ for the 5L by Shannon’s J′ for the 3L (J′5L/J′3L), respectively, with H′/J′ ≥1 showing the 5L descriptive classification system to be more informative than the 3L.

2.6 Inconsistencies

Due to the two additional response levels, we expect a redistribution that can be quantified with the help of the parameters already described (i.e. classical distribution properties on the one hand and Shannon’s indices on the other). In order to assess whether this redistribution of responses is conclusive in terms of content, we also considered inconsistent responses, as defined by Janssen et al. [8], as a qualitative distribution parameter, or if, and to what degree, 3L and 5L response pairs differ from each other. Operationally, we (1) transformed the 3L response levels 1, 2 and 3 to 5L response levels 1, 3 and 5 to calculate (2) the size of difference of corresponding responses. Paired responses differing more than one level were defined as ‘inconsistent’, with a size of inconsistency ranging from 1 to 3. All studies included in the review used the methods of Janssen et al. [8] to calculate inconsistencies.

We report and compare the percentage of inconsistencies by dimension, the range of percentage of inconsistencies by dimension, and the total number and average of inconsistencies. Notwithstanding the fact that the mere presence of inconsistent responses does not provide any information about the underlying causes, their consideration is of particular interest when they occur systematically, e.g. only in certain patient groups, which could affect validity, responsiveness and reliability.

2.7 Responsiveness

To evaluate how the instruments capture changes in health over time, we collected all reported distribution-based effect sizes (ESs), such as the standardized ES and the standardized response mean (SRM), and non-parametric test statistics, such as the Wilcoxon signed-rank order test or the probability of superiority (PS) as defined by Grissom and Kim [29]. The ES is the mean change divided by the standard deviation of the baseline measurement. It disregards the variation in change which is considered by the SRM (the ratio of the mean change to the standard deviation of the change). The Wilcoxon test is the non-parametric equivalent of the t-test for dependent samples and is applied when the prerequisites for a parametric procedure are not met.

2.8 Test–Retest Reliability

Several methods can determine whether a measurement tool consistently produces the same results if the attribute of interest remains stable [30, 31]. We extracted and summarized any reported information regarding the magnitude of agreement of data collected at two points in time: intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs), Cohen’s Kappa (κ), weighted Kappa (wκ), and percentage of agreement (POA).

An ICC quantifies the dependency of interval-scaled data pairs if the order of measurement is negligible. Values range from -1 to 1 with values less than 0 indicating a reliability of 0 and values higher or equal to 0.70 indicating good reliability [32].

κ is the most widely used measure to assess the agreement for categorical data [33]; it measures the random corrected degree of agreement between two ratings. In contrast to the simple percentage of agreement of two ratings, it considers that ratings will sometimes agree or disagree by chance. When additionally taking into account the size of the deviation (one vs. several categories) within ordinal-scaled data (such as the EQ-5D responses), calculating wκ is indicated [34]. Kappa is 1 if two ratings perfectly match, and 0 when agreement equals chance. Kappa is negative if the match is poorer than chance [35]. Note that a wκ using quadratic weights is one type of ICC. Based on the Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS), a κ > 0.40 and ICCs >0.6 were considered acceptable [30].

3 Results

Of the 497 studies identified from the search, 215 were selected for full-text review based on title and abstract screening. Of those, 190 did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded. The remaining 20 articles that compared methodical properties of the official versions of the 3L and 5L were included in the review (Fig. 1 [36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59]). An update carried out in the course of the manuscript revision resulted in a further four hits, therefore the final review is based on a total of 24 articles. All papers were of good to excellent quality (see the ESM).

The sample size of the included articles ranged from 50 to 7294 for the 3L, and 50 to 6800 for the 5L (Table 2). Data were collected in 18 different countries in the following settings: general population (8 studies) and patient populations (16 studies). All but two studies directly compared the 3L and the 5L (head-to-head, i.e. the same respondents completed both the 3L and 5L questionnaires). In head-to-head comparison studies, the 5L was administered before the 3L (Table 3). Two of the crossover studies (i.e. studies that randomized the administration order of the 3L and 5L) reported that order of administration had no influence on response trends [37, 43].

3.1 Missing Values and Distributional Properties

Fifteen studies reported missing values below 5% for both 3L (range for the dimensions: 0–1.9%; range for the profile: 0–6.6%) and 5L (range for the dimensions: 0–1.6%; range of the profile: 0–4.0%). One study found 8.5% left the 5L blank and 0.8% left the 3L blank entirely, which is probably due to the methodology of how the 3L is first presented in this study [52]. Floor effects by dimension were reported in 19 studies and were almost always below 5% (3L: 0–26.1%; 5L: 0–6.5%) [Table 4]. Mean absolute reduction in floor effects ranged from 0.16 percentage points (Usual Activities) to 4.18 percentage points (Pain/Discomfort). For the profile, floor effects ranged from 0 to 2.7% for the 3L and 0 to 1.8% for the 5L (five studies).

All studies reported information on the number or proportion reporting ‘no problems’ in any dimension or for the profile (‘11111’) [Table 4]. The percentage reporting ‘no problems’ ranged from 2.3 to 99.5% for the 3L and from 0.6 to 99.5% for the 5L. Using the 5L could reduce ceiling effects up to 16.9 percentage points (Mobility) to 30.0 percentage points (Self-Care). The highest absolute reduction of ceiling effects was found for Self-Care (−1.3 to 30.0 percentage points), followed by Pain/Discomfort (1.5 to 20.0 percentage points), and Anxiety/Depression (−3.4 to 19.7 percentage points). Regarding the profile, full health state profiles were reported for 0.6 to 68.0% of the samples studied with the 3L, compared with 0 to 55.0% of the samples studied with the 5L (Fig. 2).

Figure 3 presents the pooled ceiling effects (proportion reporting ‘11111’) for studies using patient (16 studies) and population (8 studies) samples. The pooled proportion of ceiling in the patient population was 0.23 [confidence interval (CI) 0.170–0.296] for 3L and 0.18 (CI 0.131–0.238) for 5L. Furthermore, the pooled proportion of ceiling in population-based studies was 0.53 (CI 0.474–0.593) for 3L, compared with 0.43 (CI 0.369–0.492) for 5L. The pooled proportions did not change substantially when excluding the two studies that did not use direct head-to-head comparisons (3L = 0.55, CI 0.472–0.623; 5L = 0.44, CI 0.367–0.517).

3.2 Informativity

Fourteen studies provided information on Shannon’s H′ and Shannon’s J′. In general, Shannon’s H′ was always higher in the 5L than in the 3L, and Shannon’s J′ was higher for the 5L than the 3L, in all but five studies. Across all studies and dimensions, mean Shannon’s H′ ranged from 0.72 to 1.43 for the 5L and from 0.47 to 0.98 for the 3L (Fig. 4). Mean information gain for Shannon’s H′ (H′5L/H′3L) ranged from 1.44 for Anxiety/Depression to 1.65 for Mobility. Shannon’s J′ differences between the 3L and the 5L were marginal (Fig. 4), with a mean information gain (J′5L/J′3L) ranging from 1.02 for Self-Care to 1.16 for Mobility.

3.3 Inconsistencies

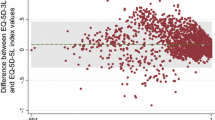

Eighteen studies provided information on inconsistencies. The total number and proportion of inconsistencies were, with four exceptions, well below 5%, ranging from 0 to 10.6% across 18 studies (Fig. 5). The most inconsistencies were reported for Usual Activities (mean percentage 4.1%), whereas the lowest number of inconsistencies was found for Mobility (2.5%). The total proportion of inconsistencies was lowest (range 0–5.4%) in healthy and chronic populations and highest (range 6–10.6%) in orthopedic settings (Fig. 5).

3.4 Responsiveness

Of the three studies analyzing responsiveness, two studies examined the index-level utility scores (using preference-based weights) [42, 45], whereas one study assessed responsiveness on the dimensional-level using percentage of improved, stable and deteriorated patients, and PS, a measure defined by Grissom and Kim [29, 37]. Distribution-based ES measures were only included in one of these studies [42]. In this longitudinal cohort, stroke patients were classified into three groups of improved, stable and deteriorated patients based on two external criteria: the Barthel Index and the modified Rankin Scale. Although both the 3L and the 5L were responsive, showing moderate ES and SRM, the 5L appeared to be (slightly) less responsive than the 3L but more responsive than the EQ-VAS. The other two studies overall found better responsiveness for the 5L compared with the 3L when using non-parametric test statistics in populations of liver disease patients and inpatient rehabilitation patients (Table 5) [37, 45]. Importantly, the two studies [42, 45] that analyzed the EQ-5D-5L on the index-level estimated index values using the crosswalk method, which maps 3L preference weights onto the 5L responses, which should be considered when interpreting these results.

3.5 Test–Retest Reliability

Six articles studied the reproducibility of the EQ-5D measure, with all but one specifying two or more measures of agreement. ICC was used in all six studies—wκ and POA in three studies, and Kappa in two studies. The time interval between repeated measurements varied from 1 to 3 weeks (Table 6). When using ICC, the studies reported moderate to excellent reproducibility for both 3L and 5L index scores, with ICC ranging from 0.52 to 0.83 for the 3L and from 0.69 to 0.93 for the 5L. When using unweighted Kappa, studies reported good to very good agreement (κ3L = 0.39–0.93, κ5L = 0.36–0.98, mean κ3L = 0.692, mean κ5L = 0.678), while studies using wκ statistics found mostly fair to moderate agreement (wκ3L = 0.31–0.70, wκ5L = 0.33–0.69, mean wκ3L = 0.527, mean wκ5L = 0.541). There is no clear pattern of better reliability for either the 3L or the 5L. POA was always the same or higher for the 3L when compared with the 5L (POA3L = 0.78–0.97, POA5L = 0.64–0.97, mean POA3L = 0.877, mean POA5L = 0.773).

4 Discussion

The EQ-5D-5L was developed to improve the discriminative and evaluative properties of the EQ-5D-3L. Since publication of the 5L, a body of evidence has emerged that allows us to determine whether it has improved upon those properties. This review systematically summarizes the evidence of studies comparing the methodological properties of the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L, with a special focus on redistribution of responses, including ceiling effects, floor effects, inconsistent responses, reliability and responsiveness. In the face of the reviewed results, both instruments demonstrated appropriateness for use in a wide range of study populations, addressing a variety of research questions and using different study designs. They show (1) the 5L responses logically distribute from the 3L, and (2) the 5L has advantages in terms of ceiling, (re-)distribution/distributional properties and how the descriptive system is used, but there are (3) some areas, such as responsiveness, in which the evidence is mixed and further research is needed. Furthermore, other aspects beyond the reviewed methodological parameters are important when choosing between 3L and 5L.

The low percentage of inconsistencies found in head-to-head studies demonstrates that the 3L redistributes logically to the 5L and that results of the 5L and 3L are comparable. The 5L is successful in reducing ceiling effects; a smaller proportion of respondents reported ‘11111’ on the 5L than on the 3L, especially in healthier samples. Thus, the 5L is suggested if the main goal is to discriminate among patients with milder health states. Moreover, the 5L outperformed the 3L when considering Shannon’s H′, with H′ being approximately 1.5-fold higher for the 5L compared with the 3L, without a relevant decrease of J′.

Missing values are negligible for both instruments demonstrating acceptance by respondents. Floor effects are also negligible for both instruments, meaning few respondents reported having the third or fifth levels of function in EQ-5D dimensions (e.g. ‘unable to wash or dress myself’). Most value sets assign negative weights to poor EQ-5D health states, meaning respondents valued many of these health states as worse than death (death is anchored at zero).

There is mixed evidence for better reliability on dimensional level, while evidence on index values shows better performance of 5L. Evidence on comparative responsiveness of the 3L and 5L is mixed [37, 42, 45]. This is surprising since adding levels to the 3L was intended to improve the responsiveness of the 3L. While two studies found the 5L to be slightly more responsive than the 3L when using non-parametric test statistics, Golicki et al. [42] found the crosswalk-derived 5L index to be less responsive than the 3L index when using several distribution-based approaches. There could be an explanation for why Golicki et al. conflicted with the other two studies. Crosswalk-derived utility scores tend to underdetect health gains [60,61,62]. For a preference-based instrument, it may be more appropriate to assess how changes in 5L versus 3L index scores are reflected in incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) or quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) [63]. Furthermore, differences with how participants value 3L versus 5L health states must be more closely examined [64, 65]. More research into sensitivity to change of the 5L and 3L is needed.

4.1 Limitations

This review has several limitations. Although all but two studies directly compared the 3L and the 5L, there are several reasons that the results of this review are difficult to generalize. The data have been derived from (1) different studies, (2) sampled from different population or patient samples, (3) use different language versions or values sets of the EQ-5D, and (4) use varying research designs (e.g. order of 3L vs. 5L, placing other, and how many, questionnaires in between 3L and 5L). Due to the differing methods, designs, analyses and potential cross-cultural differences in EQ-5D response patterns [66], it was difficult to summarize results. There are no guidelines for preference-based measures or established guidelines and standards (such as, for example, COSMIN). The EuroQol Group could create a task force to develop reporting standards in order to ensure future studies are well-defined and use more homogenous methods.

However, choosing between using the 3L and 5L requires consideration of aspects beyond methodological characteristics (which were specifically addressed in the scope of this review), such as setting and respondents, purpose of use, and availability of instruments and value sets. For all self-assessment instruments, and for preference-based instruments in particular, the choice of instrument should always take into account the perspective of those who complete the instrument, i.e. patients or respondents. There is evidence that patients prefer the 5L to the 3L, although the reason is not clear [8, 45, 67]. Fewer patients reported problems filling in the EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, and more patients deem the 5L to be easier to answer than the 3L and can find statements to describe their own health state on the 5L.

Another crucial aspect is the available language version, and, related to that, the availability of a value set to calculate the index score for the target population. Currently, both the 3L and 5L are available in more than 120 languages (3L: >170; 5L: >130) and for various administration modes (www.euroqol.org). To calculate an index score, the availability of a value set for the target population is necessary. The number of value sets available for the 3L (at least 27) is much larger than for the 5L (at least 8), with the crosswalk serving as the interim scoring method, while population-specific 5L value sets are being developed. There are also some cases where a 5L value set is available but a 3L is not; for those situations, population-specific 3L scores cannot be calculated.

5 Conclusions

This review supports the use of both the 3L and the 5L in a broad range of patients, populations, and countries. The 5L performs slightly better in terms of reducing ‘ceiling’ effects, and similarly in many other distributional properties. More research must be conducted to clarify both instruments’ performance on sensitivity to change and reliability, for which our review found mixed results from a few studies. The EuroQol group considering guiding end users with the decision to use the 5L or 3L as the choice of instrument would be based on aspects beyond measurement properties. The evidence presented in this paper can benefit the development of new EQ-5D versions, such as a 5L version of the child-friendly EQ-5D-Y [68], or exploring additional dimensions to the current five-dimension format (‘bolt-ons’) [69, 70].

References

Devlin NJ, Brooks R. EQ-5D and the EuroQol Group: Past, Present and Future. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(2):127–37.

Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37(1):53–72.

Devlin NJ, Krabbe PF. The development of new research methods for the valuation of EQ-5D-5L. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(Suppl. 1):1–3.

Szende A, Oppe M, Devlin N. EQ-5D value sets: inventory, comparative review and user guide. EuroQol Group Monographs ed. Dordrecht: Springer; 2007.

Dyer MTD, Goldsmith KA, Sharples LS, Buxton MJ. A review of health utilities using the EQ-5D in studies of cardiovascular disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:13.

Prieto L, Novick D, Sacristan JA, Edgell ET. Alonso J, on behalf of the SOHO Study Group. A Rasch model analysis to test the cross-cultural validity of the EuroQoL-5D in the Schizophrenia Outpatient Health Outcomes Study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107(Suppl. 416):24–9.

Luo N, Chew LH, Fong KY, Koh DR, Ng SC, Yoon KH, Vasoo S, Li SC, Thumboo J. Validity and reliability of the EQ-5D self-report questionnaire in English-speaking Asian patients with rheumatic diseases in Singapore. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(1):87–92.

Janssen MF, Birnie E, Haagsma JA, Bonsel GJ. Comparing the standard EQ-5D three-level system with a five-level version. Value Health. 2008;11(2):275–84.

Lloyd A. EQ-5D: Moving from Three Levels to Five. Editorial. Value Health. 2018;21(1):57–8.

Payakachat N, Ali MM, Tilford JM. Can the EQ-5D detect meaningful change? A systematic review. PharmacoEconomics. 2015;33(11):1137–54.

Johnson JA, Pickard AS. Comparison of the EQ-5D and SF-12 health surveys in a general population survey in Alberta, Canada. Med Care. 2000;38(1):115–21.

Lubetkin E, Jia H, Gold MR. Construct validity of the EQ-5D in low-income Chinese American primary care patients. Qual Life Res. 2004;13(8):1459–68.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National Healthcare Quality Report. 2003.

Kopec JA, Willison KD. A comparative review of four preference-weighted measures of health-related quality of life. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56(4):317–25.

Moock J, Kohlmann T. Comparing preference-based quality-of-life measures: results from rehabilitation patients with musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, or psychosomatic disorders. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(3):485–95.

Szende A, Leidy NK, Stahl E, Svensson K. Estimating health utilities in patients with asthma and COPD: evidence on the performance of EQ-5D and SF-6D. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(2):267–72.

Richardson J, Iezzi A, Khan A, Chen G, Maxwell A. Measuring the sensitivity and construct validity of 6 utility instruments in 7 disease areas. Med Decis Making. 2016;36(2):147–59.

Sintonen H. Comparing properties of the 15D and the EQ-5D in measuring health-related quality of life. Arch Hell Med. 2001;18(2):156–60.

Marra CA, Woolcott JC, Kopec JA, Shojania K, Offer R, Brazier JE, Esdaile JM, Anis AH. A comparison of generic, indirect utility measures (the HUI2, HUI3, SF-6D, and the EQ-5D) and disease-specific instruments (the RAQoL and the HAQ) in rheumatoid arthritis. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60(7):1571–82.

Papaioannou D, Brazier J, Parry G. How valid and responsive are generic health status measures, such as EQ-5D and SF-36, in schizophrenia? A Systematic Review. Value Health. 2011;14(6):907–20.

Obradovic M, Lal A, Liedgens H. Validity and responsiveness of EuroQol-5 dimension (EQ-5D) versus Short Form-6 dimension (SF-6D) questionnaire in chronic pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:110.

Bonsel G, van Agt H. The number of levels in the descriptive system. Rotterdam: Institute of Medical Technology Assessment; 1994. p. 115–20.

Kind P, Macran S. Levelling the playing field: increasing the number of response categories in EQ-5D. 19th Plenary Meeting of the EuroQol Group Discussion Papers. New York, Centre for Health Economics; 2002. pp. 311–22.

Van Reenen M, Janssen B. EQ-5D-5L User Guide, Basic Information on how to use the EQ-5D-5L instrument. Version 2.1. EuroQol Research Foundation; 2015.

Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen M, Kind P, Parkin D, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727–36.

NIH National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Study quality assessment tools. 2017. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools. Accessed 30 Mar 2017

Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(1):34–42.

Teachmann J. Analysis of population diversity. Sociol Methods Res. 1980;8:341–62.

Grissom RJ, Kim JJ. Effect sizes for research: Univariate and multivariate applications. 2nd ed. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2012.

Kottner J, Audigé L, Brorsonc S, Donner A, Gajewski BJ, Hróbjartsson A, Roberts C, Shoukri M, Streiner DL. Guidelines for reporting reliability and agreement studies (GRRAS) were proposed. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:96–106.

Watson PF, Petrie A. Method agreement analysis: a review of correct methodology. Theriogenology. 2010;73:1167–79.

Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(2):420–8.

Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med. 2005;37(5):360–3.

Spitzer RL, Cohen J, Fleiss JL, Endicott J. Quantification of agreement in psychiatric diagnosis. A new approach. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1967;17(1):83–7.

Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficent as measures of reliability. Educ Psychol Meas. 1973;33:613–9.

Agborsangaya CB, Lahtinen M, Cooke T, Johnson JA. Comparing the EQ-5D 3L and 5L: measurement properties and association with chronic conditions and multimorbidity in the general population. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:74.

Buchholz I, Thielker K, Feng YS, Kupatz P, Kohlmann T. Measuring changes in health over time using the EQ-5D 3L and 5L: a head-to-head comparison of measurement properties and sensitivity to change in a German inpatient rehabilitation sample. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(4):829–35.

Conner-Spady BL, Marshall DA, Bohm E, Dunbar MJ, Loucks L, Al KA, et al. Reliability and validity of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L in patients with osteoarthritis referred for hip and knee replacement. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(7):1775–84.

Craig BM, Pickard AS, Lubetkin EI. Health problems are more common, but less severe when measured using newer EQ-5D versions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(1):93–9.

Feng Y, Devlin N, Herdman M. Assessing the health of the general population in England: how do the three- and five-level versions of EQ-5D compare? Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:171.

Golicki D, Niewada M, Buczek J, Karlińska A, Kobayashi A, Janssen MF, Pickard AS. Validity of EQ-5D-5L in stroke. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(4):845–50.

Golicki D, Niewada M, Karlinska A, Buczek J, Kobayashi A, Janssen MF, et al. Comparing responsiveness of the EQ-5D-5L, EQ-5D-3L and EQ VAS in stroke patients. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(6):1555–63.

Greene ME, Rader KA, Garellick G, Malchau H, Freiberg AA, Rolfson O. The EQ-5D-5L Improves on the EQ-5D-3L for Health-related Quality-of-life Assessment in Patients Undergoing Total Hip Arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(11):3383–90.

Janssen MF, Pickard AS, Golicki D, Gudex C, Niewada M, Scalone L, Swinburn P, Busschbach J. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(7):1717–27.

Jia YX, Cui FQ, Li L, Zhang DL, Zhang GM, Wang FZ, et al. Comparison between the EQ-5D-5L and the EQ-5D-3L in patients with hepatitis B. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(8):2355–63.

Khan I, Morris S, Pashayan N, Matata B, Bashir Z, Maguirre J. Comparing the mapping between EQ-5D-5L, EQ-5D-3L and the EORTC-QLQ-C30 in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:60.

Kim TH, Jo MW, Lee SI, Kim SH, Chung SM. Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L in the general population of South Korea. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(8):2245–53.

Kim SH, Kim HJ, Lee SI, Jo MW. Comparing the psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L in cancer patients in Korea. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(6):1065–73.

Pan CW, Sun HP, Wang X, Ma Q, Xu Y, Luo N, Wang P. The EQ-5D-5L index score is more discriminative than the EQ-5D-3L index score in diabetes patients. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(7):1767–74.

Pattanaphesaj J, Thavorncharoensap M. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to EQ-5D-3L in the Thai diabetes patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:14.

Scalone L. Comparing the standard EQ-5D-3L versus 5L version for the assessment of health of patients with live diseases. EuroQol Proc. 2011;16:213–39.

Scalone L, Ciampichini R, Fagiuoli S, Gardini I, Fusco F, Gaeta L, et al. Comparing the performance of the standard EQ-5D 3L with the new version EQ-5D 5L in patients with chronic hepatic diseases. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(7):1707–16.

Scalone L, Cortesi PA, Ciampichini R, Cesana G, Mantovani LG. Health Related Quality of Life norm data of the general population in Italy: results using the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L instruments. Epidemiol Biostat Public Health. 2015;12(3):e11457-1–-15.

Shiroiwa T, Fukuda T, Ikeda S, Igarashi A, Noto S, Saito S, Shimozuma K. Japanese population norms for preference-based measures: EQ-5D-3L, EQ-5D-5L, and Sf-6D. Qual Life Res. 2016;25(3):707–19.

Wang Y, Tan NC, Tay EG, Thumboo J, Luo N. Cross-cultural measurement equivalence of the 5-level EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in Singapore. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;13:103.

Ferreira LN, Ferreira PL, Ribeiro FP, Pereira LN. Comparing the performance of the EQ-5D-3L and the EQ-5D-5L in young Portuguese adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:89.

Poór AK, Rencz F, Brodszky V, Gulácsi L, Beretzky Z, Hidvégi B, Holló P, Kárpáti S, Péntek M. Measuement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L in psoriasis patients. Qual Life Res. 2017;26:3409–19.

Yfantopoulos J, Chantzaras AE. Validation and comparison of the psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L instruments in Greese. Eur J Health Econ. 2017;18:519–31.

Yfantopoulos J, Chantzaras A, Kontodimas S. Assesment of the psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-3L and EQ-5D-5L instruments in psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309:357–70.

Golicki D, Niewada M, van Hout B, Janssen MF, Pickard AS. Interim eq-5d-5 l value set for Poland: First crosswalk value set in Central and Eastern Europe. Value Health Reg Issues. 2014;4C:19–23.

Versteegh M, Vermeulen M, Evers AA, de Wit GA, Prenger R, Stolk A. Dutch tariff for the five-level version of EQ-5D. Value Health. 2016;19(4):343–52.

Petrou S, Rivero-Arias O, Dakin H, Longworth L, Oppe M, Froud R, et al. The maps reporting statement for studies mapping onto generic preference-based outcome measures. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A715–6.

Alava MH, Wailoo A, Grimm S, Pudney S, Gomes M, Sadique Z, Meads D, O’Dwyer J, Barton G, Irvine L. EQ-5D-5L versus EQ-5D-3L: the impact on cost effectiveness in the United Kingdom. Value Health. 2018;21(1):49–56.

Luo N, Cheung YB, Ng R, Lee CF. Mapping and direct valuation: do they give equivalent EQ-5D-5L index scores? Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:166.

Devlin NJ, Shah KK, Feng Y, Mulhern B, van Hout B. Valuing health-related quality of life: An EQ-5D-5L value set for England. Health Econ. 2018;27(1):7–22.

Feng Y, Herdman M, van Nooten F, Cleeland C, Parkin D, Ikeda S, et al. An exploration of differences between Japan and two European countries in the self-reporting and valuation of pain and discomfort on the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(8):2067–78.

Chevalier J, De Pouvourville G. Testing a new 5 level version of the EQ-5D in France. EuroQol Proceedings. 2008;14:75–88.

Ravens-Sieberer U, Wille N, Badia X, Bonsel G, Burström K, Cavrini G, Devlin N, Egmar AC, Gusi N, Herdman M, Jelsma J, Kind P, Olivares PR, Scalone L, Greiner W. Feasibility, reliability, and validity of the EQ-5D-Y: results from a multinational study. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(6):887–97.

Yang Y, Brazier J, Tsuchiya A. Effect of adding a sleep dimension to the EQ-5D descriptive system. A “Bolt-On” experiment. Med Decis Making. 2014;34(1):42–53.

Yang Y, Rowen D, Brazier J, Tsuchiya A, Young T, Longworth L. an exploratory study to test the impact on three “Bolt-On” items to the EQ-5D. Value Health. 2015;18(1):52–60.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Associate Professor Benjamin M. Craig and Professor A. Simon Pickard for their valuable input while preparing and revising the manuscript. In particular, they would also like to thank Katrin Heyn for carefully reading and managing the references.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IB and YSF reviewed the articles and extracted and synthesized the data for this work. MFJ and TK were consulted in case of disagreement, and IB conceptualized the paper. All authors contributed to the drafting, editing, or critically reviewing of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Not applicable since this study describes a literature review.

Funding

This work was funded by the EuroQol Research Foundation (grant number EQ Project 2016170).

Conflict of interest

All authors are members of the EuroQol Group and receive or have received research grants from the EuroQol Research Foundation.

Disclaimer

The views of the authors expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect the views of the EuroQol Group. Parts of the contents of this paper were presented at the 34th EuroQol Plenary Meeting in Barcelona, Spain.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed in this review were extracted from published articles (see the ESM) and are available from the corresponding authors of the included articles.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Buchholz, I., Janssen, M.F., Kohlmann, T. et al. A Systematic Review of Studies Comparing the Measurement Properties of the Three-Level and Five-Level Versions of the EQ-5D. PharmacoEconomics 36, 645–661 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0642-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0642-5