Abstract

Background

Severe hypercholesterolemia is a major risk factor of death in patients with coronary heart disease. New adjunctive drug therapies (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 [PCSK9] inhibitors) have gained approval in Europe and the USA.

Objective

In this empirical study, we documented preferences regarding adjuvant drug therapy in apheresis-treated patients with severe familial hypercholesterolemia.

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature search to identify patient-relevant outcomes in patients with severe hypercholesterolemia currently undergoing apheresis. Data were used to generate a semi-structured qualitative interview that enabled seven patient-relevant characteristics with three levels each to be identified. For the discrete choice experiment, an experimental design (7 × 3) was generated using NGene Software that consisted of 96 choices divided into eight blocks. The survey was conducted between November 2015 and April 2016 using computer-assisted personal interviews.

Results

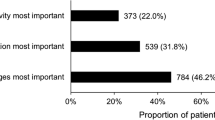

The survey was completed by 348 patients (64.9% male). The random parameter logit estimation showed predominance for the attribute ‘reduction of LDL-C (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol) level’. ‘Risk of myopathy’ and ‘frequency of apheresis’ dominated next. Within the random parameter logit estimation, all coefficients were significant (P ≤ 0.01). The latent class analysis identified three patient groups. The first group (126 patients) found ‘reduction of LDL-C level in blood’ to be most important. This group focused solely on this treatment outcome independently of apheresis frequency or additional injections. The second group (106 patients) focused on three attributes: ‘frequency of apheresis’, ‘risk of myopathy’, and ‘reduction of LDL-C level in blood’. Respondents clearly considered a high frequency of apheresis to have a negative impact. The third group (116 patients) demonstrated the highest preference for apheresis. These patients have adjusted to apheresis for > 10 years.

Conclusion

Regarding patient preference, clinical efficacy seems to dominate. Hence, ‘reduction of LDC-C in blood’ was ranked highest above patient-relevant modes of administration and adverse effects. In the patient groups identified, reduction of apheresis was important for only a subsegment (30%) of patients. Another 30% wanted effective LDL-C reduction by whatever means necessary. Most strikingly, another 30% preferred higher frequencies of apheresis.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bruckert E, Saheb S, Bonté JR, Coudray-Omnès C. Daily life, experience and needs of persons suffering from homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: insights from a patient survey. Atheroscler Suppl. 2014;15(2):46–51.

Walzer S, Travers K, Rieder S, Erazo-Fischer E, Matusiewicz D. Homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HoFH) in Germany: an epidemiological survey. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:189.

Goldberg AC, Hopkins PN, Toth PP, Ballantyne CM, Rader DJ, Robinson JG, et al. Familial hypercholesterolemia: screening, diagnosis and management of pediatric and adult patients: clinical guidance from the National Lipid Association Expert Panel on Familial Hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Lipidol. 2011;5(3):133–40.

Raal FJ, Santos RD. Homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: current perspectives on diagnosis and treatment. Atherosclerosis. 2012;223(2):262–8.

Bruckert E. Recommendations for the management of patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: overview of a new European Atherosclerosis Society consensus statement. Atheroscler Suppl. 2014;15(2):26–32.

Santos RD. What are we able to achieve today for our patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia, and what are the unmet needs? Atheroscler Suppl. 2014;15(2):19–25.

Julius U. Lipoprotein apheresis in the management of severe hypercholesterolemia and of elevation of lipoprotein (a): current perspectives and patient selection. Med Dev (Auckl). 2016;9:349–60.

Vogt A. The genetics of familial hypercholesterolemia and emerging therapies. Appl Clin Genet. 2015;8:27–36.

Stefanutti C, Julius U. Lipoprotein apheresis: state of the art and novelties. Atheroscler Suppl. 2013;14(1):19–27.

Moriarty PM, Parhofer KG, Babirak SP, Cornier M-A, Duell PB, Hohenstein B, et al. Alirocumab in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia undergoing lipoprotein apheresis: the ODYSSEY ESCAPE trial. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(48):3545–8.

Olshavsky RW, Granbois DH. Consumer decision making—fact or fiction? J Consumer Res. 1979;6(2):93–100.

Johnson FR. Why not ask? Measuring patient preferences for healthcare decision making. Patient. 2008;1(4):245–8.

Laine C, Davidoff F. Patient-centered medicine: a professional evolution. JAMA. 1996;275(2):152–6.

Trope Y, Liberman N. Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychol Rev. 2010;117(2):440.

Ford S, Schofield T, Hope T. What are the ingredients for a successful evidence-based patient choice consultation? A qualitative study. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(3):589–602.

Edwards A, Elwyn G, Wood F, Atwell C, Prior L, Houston H. Shared decision making and risk communication in practice: a qualitative study of GPs’ experiences. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(510):6.

Edwards A, Elwyn G. Inside the black box of shared decision making: distinguishing between the process of involvement and who makes the decision. Health Expect. 2006;9(4):307–20.

Speedling EJ, Rose DN. Building an effective doctor-patient relationship: from patient satisfaction to patient participation. Soc Sci Med. 1985;21(2):115–20.

Holmes-Rovner M, Valade D, Orlowski C, Draus C, Nabozny-Valerio B, Keiser S. Implementing shared decision-making in routine practice: barriers and opportunities. Health Expect. 2000;3(3):182–91.

Mühlbacher A, Johnson FR. Choice experiments to quantify preferences for health and healthcare: state of the practice. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2016;14(3):253–66.

Mühlbacher A, Juhnke C. Patient preferences versus physicians’ judgement: does it make a difference in healthcare decision making? Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11(3):163–80.

Kennedy HL. The importance of randomized clinical trials and evidence-based medicine: a clinician’s perspective. Clin Cardiol. 1999;22(1):6–12.

Johnson FR, Beusterien K, Özdemir S, Wilson L. Giving patients a meaningful voice in United States regulatory decision making: the role for health preference research. Patient. 2017;10(4):523–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-017-0250-z

Mühlbacher AC, Johnson FR. Giving patients a meaningful voice in European health technology assessments: the role of health preference research. Patient. 2017;10(4):527–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-017-0249-5

Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlicheit im Gesundheitswesen (IQWiG). Wahlbasierte Conjoint-Analyse—Pilotprojekt zur Identifikation, Gewichtung und Priorisierung multipler Attribute in der Indikation Hepatitis C; IQWiG-Berichte—Nr. 227 [Pilot study: Conjoint Analysis in the indication “hepatitis C”]. Köln; 2014. https://www.iqwig.de/en/projects-results/projects/health-economic/ga10-03-pilot-study-conjoint-analysis-in-the-indication-hepatitis-c.1411.html. Accessed 24 Jan 2018.

Alonso-Coello P, Montori VM, Díaz MG, Devereaux PJ, Mas G, Diez AI, et al. Values and preferences for oral antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation: physician and patient perspectives. Health Expect. 2015;18(6):2318–27.

Cutler D, Skinner J, Stern AD, Wennberg D. Physician beliefs and patient preferences: a new look at regional variation in health care spending. NBER Working Paper no. 19320. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2013.

Orme B. Getting started with conjoint analysis. Madison: Research Publishers LLC; 2010.

Yang J-C, Johnson FR, Kilambi V, Mohamed AF. Sample size and utility-difference precision in discrete-choice experiments: a meta-simulation approach. J Choice Model. 2015;16:50–7.

de Bekker-Grob EW, Donkers B, Jonker MF, Stolk EA. Sample size requirements for discrete-choice experiments in healthcare: a practical guide. Patient. 2015;8(5):373–84.

Lancaster KJ. A new approach to consumer theory. J Polit Econ. 1966;74(2):132–57.

McFadden D. Conditional logit analysis of qualitative choice behavior. Zarembka. 1974;1974:105–42.

Ben-Akiva ME, Lerman SR. Discrete choice analysis: theory and application to travel demand. Cambridge: MIT; 1985.

Hensher DA, Rose JM, Greene WH. Applied choice analysis: a primer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005.

Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making: a user’s guide. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(8):661–78.

Bridges J, Hauber A, Marshall D, Lloyd A, Prosser L, Regier D, et al. Checklist for conjoint analysis applications in health: report of the ISPOR Conjoint Analysis Good Research Practices Taskforce. Value Health. 2009;14(4):403–13.

Mühlbacher A, Bethge S, Tockhorn A. Präferenzmessung im Gesundheitswesen: Grundlagen von Discrete-Choice-Experimenten. Gesundheitsökonomie Qualitätsmanagement. 2013;18(4):159–72.

Bridges JF, Kinter ET, Kidane L, Heinzen RR, McCormick C. Things are looking up since we started listening to patients: trends in the application of conjoint analysis in health 1982–2007. Patient. 2008;14(4):273–82.

Louviere JJ, Hensher DA, Swait JD. Stated choice methods: analysis and application. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

Ryan M, Gerard K, Amaya-Amaya M. Using discrete choice experiments to value health and health care. Dordrecht: Springer; 2008.

Mühlbacher AC, Kaczynski A, Dippel F-W, Bethge S. Patient priorities in adjunctive drug therapy of severe hypercholesterolemia in Germany: an analytic hierarchy process (AHP). Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2017 (in press).

US Department of Health and Human Services. Common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) version 4.03. Bethesda: National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2010.

ChoiceMetrics. NGene. http://www.choice-metrics.com. Accessed 24 Jan 2018.

Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A, Pickles A. GLLAMM manual. Division of Biostatistics Working Paper Series. Berkeley: University of California; 2004.

IBM Corp. Released 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20.0. Armonk: IBM Corp.; 2011.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: release 13. College Station: StataCorp LP; 2013.

Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Model. 2007;14(4):535–69.

Yang C-C. Evaluating latent class analysis models in qualitative phenotype identification. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2006;50(4):1090–104.

Hess S, Ben-Akiva M, Gopinath D, Walker J. Advantages of latent class choice models over continuous mixed logit models. In: Proceedings of the 12th international conference on travel behaviour research; 13–18 Dec 2009; Jaipur.

Shen J. Latent class model or mixed logit model? A comparison by transport mode choice data. Appl Econ. 2009;41(22):2915–24.

Hess S. Chapter 14: Latent class structures: taste heterogeneity and beyond. In: Hess S, Daly A, editors. Handbook of choice modelling. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited; 2014. p. 311–30.

Roth EM, Bujas-Bobanovic M, Louie MJ, Cariou B. Patient and physician perspectives on mode of administration of the PCSK9 monoclonal antibody alirocumab, an injectable medication to lower LDL-C levels. Clin Ther. 2015;37(9):1945–54 e6.

Tatlock S, Grant L, Spertus JA, Khan I, Arbuckle R, Manvelian G, et al. Development and content validity testing of a patient-reported treatment acceptance measure for use in patients receiving treatment via subcutaneous injection. Value Health. 2015;18(8):1000–7.

Tatlock S, Grant L, Arbuckle R, Khan I, Manvelian G, Sanchez R. Development and content validity testing of a treatment acceptance measure for use in hypercholesterolemia patients receiving treatment via subcutaneous injection. Value Health. 2014;17(7):A569.

Klose G, Laufs U, Marz W, Windler E. Familial hypercholesterolemia: developments in diagnosis and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(31–32):523–9.

Robinson JG, Farnier M, Krempf M, Bergeron J, Luc G, Averna M, et al. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(16):1489–99.

Blinman P, Alam M, Duric V, McLachlan SA, Stockler MR. Patients’ preferences for chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review. Lung Cancer. 2010;69(2):141–7.

Mühlbacher A, Bethge S. Patients’ preferences: a discrete-choice experiment for treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Health Econ. 2015;16(6):657–70.

Burke PF, Burton C, Huybers T, Islam T, Louviere JJ, Wise C. The scale-adusted latent class model: application to museum visitation. Tour Anal. 2010;15(2):147–65.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Spreeconsult GmbH for conducting the survey interviews. Susanne Bethge made technical contributions to the organization of the study and the early study design and assisted in the pretesting of the survey. Finally, the authors would like to thank all survey participants.

Funding

This study was financed by Sanofi Deutschland GmbH, Berlin, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Axel Mühlbacher designed and directed this study as the principal investigator. Axel Mühlbacher and Andrew Sadler conceived and planned the experimental design of the study. Andrew Sadler performed analysis on all samples. Axel Mühlbacher, Andrew Sadler, and Christin Juhnke contributed to the interpretation of the results. Christin Juhnke helped with the qualitative interviews and took the lead in preparing the manuscript. Franz-Werner Dippel provided critical feedback and commented on the manuscript. All authors finally approved the latest version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Axel Mühlbacher, Andrew Sadler, and Christin Juhnke declare that they have no further conflicts of interest. Franz-Werner Dippel was an employee of Sanofi Deutschland GmbH during the time of the conduction of this study.

Data availability

The datasets on the respondents’ choices generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mühlbacher, A.C., Sadler, A., Dippel, FW. et al. Treatment Preferences in Germany Differ Among Apheresis Patients with Severe Hypercholesterolemia. PharmacoEconomics 36, 477–493 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0614-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-018-0614-9