Abstract

Background

Despite the rapid development of effective treatments, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological, insomnia management remains suboptimal at the practice interface. Patient preferences play a critical role in influencing treatment outcomes. However, there is currently a mismatch between patient preferences and clinician recommendations, partly perpetuated by a limited understanding of the patients’ decision-making process.

Objectives

The aim of our study was to empirically quantify patient preferences for treatment attributes common to both pharmacological and non-pharmacological insomnia treatments.

Method

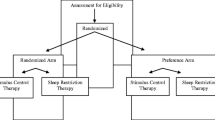

An efficient dual-response discrete choice experiment was conducted to evaluate patient treatment preferences for managing insomnia. The sample included 205 patients with self-reported insomnia and an Insomnia Severity Index ≥ 14. Participants were presented with two unlabelled hypothetical scenarios with an opt-out option across 12 choice sets. Data were analyzed using a mixed multinomial logit model to investigate the influence of five attributes (i.e. time, onset of action, maintainability of improved sleep, length of treatment, and monthly cost) on treatment preferences.

Results

Treatments were preferentially viewed if they conferred long-term sleep benefits (p < 0.05); had an ongoing, as opposed to a predefined, duration of treatment course (p < 0.05); required some, as opposed to no, additional time commitment (p < 0.05); and had lower monthly out-of-pocket treatment costs (p < 0.001). However, treatment onset of action had no influence on preference. Age, help-seeking status, concession card status and fatigue severity significantly influenced treatment preference.

Conclusion

Participants’ prioritization of investing time in treatment and valuing the maintainability of therapeutic gains suggests a stronger inclination towards non-pharmacological treatment, defying current assumptions that patients prefer ‘quick-fixes’ for managing insomnia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Benzodiazepine receptor agonists, e.g. temazepam and zolpidem.

Cognitive behavioural treatment for insomnia (CBT-I).

The Woolcock Institute of Medical Research (WIMR), Sydney, Australia, and Brain and Mind Centre (formerly Brain and Mind Research Institute), Sydney, Australia.

General Practice Clinics and Community Pharmacy.

Sleep Disorders Australia is a group that aims to provide information and support to individuals with sleep disorders and their families (https://www.sleepoz.org.au/)

The attribute levels for cost (i.e. $15, $30, $60, $120 and $240) were informed by an estimation of the cost of a private prescription for zolpidem at $19, the recommended fee schedule of $181 for a 31- to 45-min consultation with a psychologist in 2015. We also accounted for patients’ willingness to pay $40 into the cost attribute levels.

DASS-21 reported as three separate subscales for Depression, Anxiety and Stress symptoms.

References

Ohayon M. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6(2):97–111.

Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA, Cooke M, Denberg TD. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(2):125–33.

Morin CM, LeBlanc M, Daley M, Gregoire JP, Merette C. Epidemiology of insomnia: prevalence, self-help treatments, consultations, and determinants of help-seeking behaviors. Sleep Med. 2006;7(2):123–30.

Dyas JV, Apekey TA, Tilling M, Orner R, Middleton H, Siriwardena AN. Patients’ and clinicians’ experiences of consultations in primary care for sleep problems and insomnia: a focus group study. Br J Gen Pract. 2010;60(574):e180–200.

Sirdifield C, Chipchase SY, Owen S, Siriwardena AN. A systematic review and meta-synthesis of patients’ experiences and perceptions of seeking and using benzodiazepines and Z-drugs: towards safer prescribing. Patient. 2017;10(1):1–15.

Kripke DF. Mortality risk of hypnotics: strengths and limits of evidence. Drug Saf. 2016;39(2):93–107.

Panneman MJM, Goettsch WG, Kramarz P, Herings RMC. The costs of benzodiazepine-associated hospital-treated fall injuries in the EU: a pharmo study. Drugs Aging. 2003;20(11):833–9.

Pollmann AS, Murphy AL, Bergman JC, Gardner DM. Deprescribing benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in community-dwelling adults: a scoping review. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;16:19.

Mitchell M, Gehrman P, Perlis M, Umscheid C. Comparative effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:40.

Kaufmann CN, Spira AP, Alexander GC, Rutkow L, Mojtabai R. Trends in prescribing of sedative-hypnotic medications in the USA: 1993–2010. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(6):637–45.

Vincent N, Lionberg C. Treatment preference and patient satisfaction in chronic insomnia. Sleep. 2001;24(4):411–7.

Bluestein D, Healey AC, Rutledge CM. Acceptability of behavioral treatments for insomnia. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(3):272–80.

Légaré F, Witteman HO. Shared decision making: examining key elements and barriers to adoption into routine clinical practice. Health Aff. 2013;32(2):276–84.

Morin CM, Gaulier B, Barry T, Kowatch RA. Patients’ acceptance of psychological and pharmacological therapies for insomnia. Sleep. 1992;15(4):302–5.

Bouchard S, Bastien C, Morin CM. Self-efficacy and adherence to cognitive-behavioral treatment of insomnia. Behav Sleep Med. 2003;1(4):187–99.

Vincent N, Lewycky S, Finnegan H. Barriers to engagement in sleep restriction and stimulus control in chronic insomnia. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76(5):820–8.

Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572–8.

Horne R. Patients’ beliefs about treatment: The hidden determinant of treatment outcome? J Psychosom Res. 1999;47(6):491–5.

Johnson FR, Lancsar E, Marshall D, Kilambi V, Mühlbacher A, Regier DA, et al. Constructing experimental designs for discrete-choice experiments: report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis experimental design good research practices task force. Value Health. 2013;16(1):3–13.

Cheung JMY, Bartlett DJ, Armour CL, Laba T-L, Saini B. To drug or not to drug: a qualitative study of patients’ decision-making processes for managing insomnia. Behav Sleep Med. 2018;16(1):1–26.

Bliemer MCJ, Rose JM, Hess S. Approximation of bayesian efficiency in experimental choice designs. J Choice Model. 2008;1(1):98–126.

Rose JM, Bliemer MCJ. Constructing efficient stated choice experimental designs. Transp Rev. 2009;29(5):587–617.

Laba T-L, Brien J-A, Fransen M, Jan S. Patient preferences for adherence to treatment for osteoarthritis: the MEdication Decisions in Osteoarthritis Study (MEDOS). BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14(1):160.

de Bekker-Grob EW, Bliemer MCJ, Donkers B, Essink-Bot ML, Korfage IJ, Roobol MJ, et al. Patients’ and urologists’ preferences for prostate cancer treatment: a discrete choice experiment. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(3):633–40.

Pearmain D. Stated preference techniques: a guide to practice. London: Steer Davies Gleave; 1991.

Veldwijk J, Lambooij MS, de Bekker-Grob EW, Smit HA, de Wit GA. The effect of including an opt-out option in discrete choice experiments. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e111805.

Brazell JD, Diener CG, Karniouchina E, Moore WL, Séverin V, Uldry P-F. The no-choice option and dual response choice designs. Mark Lett. 2006;17(4):255–68.

Stinson K, Tang NKY, Harvey AG. Barriers to treatment seeking in primary insomnia in the United Kingdom: a cross-sectional perspective. Sleep. 2006;29(12):1643–6.

Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2(4):297–307.

Morin CM, Vallières A, Ivers H. Dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes about sleep (DBAS): validation of a brief version (DBAS-16). Sleep. 2007;30(11):1547–54.

Ng F, Trauer T, Dodd S, Callaly T, Campbell S, Berk M. The validity of the 21-item version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales as a routine clinical outcome measure. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2007;19(5):304–10.

Valko PO, Bassetti CL, Bloch KE, Held U, Baumann CR. Validation of the fatigue severity scale in a Swiss cohort. Sleep. 2008;31(11):1601–7.

Vermeulen B, Goos P, Vandebroek M. Rank-order choice-based conjoint experiments: efficiency and design. J Stat Plan Inference. 2011;141(8):2519–31.

Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008;26(8):661–77.

Lusk JL. Effects of cheap talk on consumer willingness-to-pay for golden rice. Am J Agric Econ. 2003;85(4):840–56.

Obse A, Ryan M, Heidenreich S, Normand C, Hailemariam D. Eliciting preferences for social health insurance in Ethiopia: a discrete choice experiment. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(10):1423–32.

Bliemer MCJ, Rose JM. Confidence intervals of willingness-to-pay for random coefficient logit models. Trans Res Part B Methodol. 2013;58:199–214.

Dunne SS, Dunne CP. What do people really think of generic medicines? A systematic review and critical appraisal of literature on stakeholder perceptions of generic drugs. BMC Med. 2015;13:173.

Falloon K, Elley CR, Fernando A 3rd, Lee AC, Arroll B. Simplified sleep restriction for insomnia in general practice: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65(637):e508–15.

Ellis JG, Cushing T, Germain A. Treating acute insomnia: a randomized controlled trial of a “single-shot” of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep. 2014;38(6):971–8.

Ellis JG, Barclay NL. Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Insomnia: state of the science or a stated science? Sleep Med. 2014;15(8):849–50.

Dollman W, LeBlanc VT, Roughead E. Managing insomnia in the elderly: what prevents us using non-drug options? J Clin Pharm Ther. 2003;28(6):485–91.

Thomas A, Grandner M, Nowakowski S, Nesom G, Corbitt C, Perlis ML. Where are the behavioral sleep medicine providers and where are they needed? A geographic assessment. Behav Sleep Med. 2016;14(6):687–98.

Okada EM, Hoch SJ. Spending time versus spending money. J Consum Res. 2004;31(2):313–23.

Everitt H, McDermott L, Leydon G, Yules H, Baldwin D, Little P. GPs’ management strategies for patients with insomnia: a survey and qualitative interview study. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(619):e112–9.

Cheung JMY, Atternäs K, Melchior M, Marshall NS, Fois RA, Saini B. Primary health care practitioner perspectives on the management of insomnia: a pilot study. Aust J Prim Health. 2013;20(1):103–12.

Morgenthaler T, Kramer M, Alessi C, Friedman L, Boehlecke B, Brown T, et al. Practice parameters for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: an update. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep. 2006;29(11):1415–9.

Pieterse AH, de Vries M, Kunneman M, Stiggelbout AM, Feldman-Stewart D. Theory-informed design of values clarification methods: a cognitive psychological perspective on patient health-related decision making. Soc Sci Med. 2013;77:156–63.

Alessi C, Vitiello MV. Insomnia (primary) in older people. BMJ Clin Evid. 2011;2011:2302.

Buysse DJ, Germain A, Moul DE, et al. Efficacy of brief behavioral treatment for chronic insomnia in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(10):887–95.

Ensor T, Cooper S. Overcoming barriers to health service access: influencing the demand side. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19(2):69–79.

Aikens JE, Rouse ME. Help-seeking for insomnia among adult patients in primary care. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18(4):257–61.

Chen JA, Keller SM, Zoellner LA, Feeny NC. “How will it help me?” Reasons underlying treatment preferences between sertraline and prolonged exposure in PTSD. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201(8):691–7.

Savage SJ, Waldman DM. Learning and fatigue during choice experiments: a comparison of online and mail survey modes. J Appl Econometr. 2008;23(3):351–71.

Van de Mortel TF. Faking it: social desirability response bias in self-report research. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2008;25(4):40.

Fifer S, Rose J, Greaves S. Hypothetical bias in stated choice experiments: is it a problem? And if so, how do we deal with it? Transp Res Part A Policy Pract. 2014;61:164–77.

Acknowledgements

The current study was undertaken with financial support in the form of ‘seed funding’ provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council, CIRUS, Centre for Integrated Research and Understanding of Sleep, Woolcock Institute of Medical Research, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia (grant number 571421). Bandana Saini is the chief investigator and Janet M. Y. Cheung is the associate investigator.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JC conducted the research, analysis and writing of the initial draft of the manuscript. TL and JC conceptualized the initial econometric design for the research instrument. TL, JC BS, DB, CA refined the econometric design for the research instrument. TL provided expert advice on the econometric modelling technique and guided the data analysis. JC carried out the initial analysis and interpretation of the data. TL, DB, CA and BS provided advice on the interpretation of the data. All authors critically revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Janet M.Y. Cheung, Delwyn J. Bartlett, Carol L. Armour, Bandana Saini and Tracey-Lea Laba have no further financial or intellectual conflicts of interest to declare.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cheung, J.M.Y., Bartlett, D.J., Armour, C.L. et al. Patient Preferences for Managing Insomnia: A Discrete Choice Experiment. Patient 11, 503–514 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-018-0303-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-018-0303-y