Abstract

Background

Seriously ill people at high risk of death face difficult decisions, especially concerning the extent of medical intervention. Given the inherent difficulty and complexity of these decisions, the care they receive often does not align with their preferences. Patient decision aids that educate individuals about options and help them construct preferences about life-sustaining care may reduce the mismatch between the care people say they want and the care they receive. The quantity and quality of patient decision aids for those at high risk of death, however, are unknown.

Objective

This protocol describes an approach for conducting an environmental scan of life-sustaining treatment patient decision aids for seriously ill patients, identified online and through informant analysis. We intend for the outcome to be an inventory of all life-sustaining treatment patient decision aids for seriously ill patients currently available (either publicly or proprietarily) along with information about their content, quality, and known use.

Methods

We will identify patient decision aids in a three-step approach (1) mining previously published systematic reviews; (2) systematically searching online and in two popular app stores; and (3) undertaking a key informant survey. We will screen and assess the quality of each patient decision aid identified using the latest published draft of the U.S. National Quality Forum National Standards for the Certification of Patient Decision Aids. Additionally, we will evaluate readability via readable.io and content via inductive content analysis. We will also use natural language processing to assess the content of the decision aids.

Discussion

Researchers increasingly recognize the environmental scan as an optimal method for studying real-world interventions, such as patient decision aids. This study will advance our understanding of the availability, quality, and use of decision aids for life-sustaining interventions targeted at seriously ill patients. We also aim to provide patients, their families, and friends, along with their clinicians, a broad set of resources for making life-sustaining treatment decisions. Although we intend to capture all patient decision aids for the seriously ill in our review, we anticipate the possibility that we may miss some decision aids. In addition to publishing our findings in an academic journal, we plan to post our inventory online in an easy-to-read format for public and clinical consumption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Many tools for helping patients and families make decisions about life-sustaining treatments are available, but most have not been accounted for or rigorously evaluated, and very little is known about their use. |

Patients, families, and clinicians do not have a trusted resource for finding appropriate tools for making life-sustaining treatment decisions. |

This study aims to inventory and appraise life-sustaining treatment decision-making tools. |

1 Background

There is a mismatch between patients stated final care preferences and their actual dying experiences [1, 2]. Decision making about death is personal, complex, and multifaceted. Decisions concern the benefits and drawbacks of certain interventions, but also patients’ values and preferences [3]. Circumstances can vary from person to person but may include place of death, whether or for how long to pursue aggressive intervention, and more [4]. In light of this complexity, there is evidence that people do not consistently receive the care they want when they are dying [5]. Most people say they do not want aggressive interventions if they are dying [6,7,8]. Nearly one in five, however, die in hospitals, where they often receive aggressive care [9]. One in seven die in intensive care units, where care is even more aggressive [1].

Contributors to the mismatch between care preferences and care received are complex. There is evidence, for instance, that the majority of patients do not know ahead of time that they are dying [10]. A systematic review conducted by Applebaum and colleagues [10] found up to 75% of patients with advanced cancer were unaware of their prognosis. In some studies, patients with advanced cancer did not know they had the condition. Patients and families may also have goals that their care teams do not think are medically feasible [11]. There is also consistent evidence that patients—and by extension, their families—do not understand nearly half of the medical terminology used and may not understand or be able to differentiate between the medically feasible options given a patient’s condition [12,13,14].

Federal policies in the USA have increasingly opened the door to discussions about goals of care, and inpatient hospital deaths have decreased in recent years [1, 15, 16]. Nevertheless, care provided to patients during the last 6 months of life accounts for roughly 30% of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ total spending [17]. To reduce this burden, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced in 2015 that it would begin reimbursing for advance care planning conversations between patients and their clinicians [16]. This rule change will likely facilitate increased advance care planning discussions and documentation of advance directives in both the inpatient and outpatient settings [16]. Advance directives encompass both distal and proximal decision making; they often document preferences well before life-sustaining treatment decisions are at hand [16]. However, there is evidence that preferences are sensitive to context and people determine their preferences in the moment, not ahead of time [18]. This may make advance directives insufficient tools for proximate decision making about life-sustaining treatments [18].

Despite these legislative changes, the mismatch between dying preferences and the care patients receive persists [1]. When patients receive interventions that do not match their values and preferences, some decision-making experts call this a “preference misdiagnosis” [3]. Angelo Volandes, MD, a hospitalist and researcher goes further, asserting care that does not match a patient’s preferences is a “medical error” [19]. Shared decision making, a process through which patients and their clinicians make joint decisions about treatments and screening in light of patients’ values and preferences and what is medically possible, can help mitigate preference mismatch [20]. Shared decision making leverages evidence to weigh the benefits and harms of all potential interventions or decisions and help patients construct their choices [3, 20]. The literature suggests most patients prefer a shared decision-making approach, although it is important to note that some patients prefer arrangements that are more physician driven [6, 21]. Decision aids facilitate this process of prognosis and values-informed decision making [22]. In a 2017 review, Stacey and colleagues found patient decision aids improve patient knowledge, reduce feelings of decisional conflict, inspire a more active role in decision making, and improve understanding of risk [23]. There is also evidence that video patient decision aids detailing choices about cardiopulmonary resuscitation and intubation change patients’ preferences vs. verbal explication of options, indicating they may not have understood the choices at hand with verbal-only explanations [24, 25]. Studies also find a change in the knowledge of options after the use of patient decision aids [25].

The number of available patient decision aids for life-sustaining interventions is currently unknown. Butler and colleagues inventoried and evaluated advance care planning instruments in a 2014 review [4]. They found 16 published studies in the peer-reviewed literature that tested patient decision aids for advance care planning [4]. They also identified a number of decision aids by searching the gray literature and speaking with key informants (although how many decision aids were identified using this method is unclear) [4]. Included in their review were 19 decision aids, spanning from general population advance care planning to general decision aids for the seriously ill, to decision aids targeted at specific diseases or conditions with predictable treatment choices [4]. They report they found many more decision aids online [4]. Interestingly, they did not include the decision aids they found through online searching in their review, representing a gap in the literature [4]. Additionally, many studies of patient decision aids for life-sustaining treatments have focused on specific patient populations, or disease states [26,27,28]. However, the reality is that many adults, particularly those that are older or critically ill, have co-morbidities [29, 30]. Given this, understanding tools across various disease states and index decisions is critical. Our broader approach will provide this higher-level overview of the field.

2 Objectives and Research Questions

We will endeavor to identify, characterize, and assess the quality of all English-language patient decision aids currently available. Our research questions are as follows:

-

What English-language patient decision aids about life-sustaining treatments are available?

-

What are the characteristics of these patient decision aids?

-

What is the quality of these patient decision aids?

-

What organizations use these patient decision aids?

3 Methods

We adapted this environmental scan protocol from similar studies of patient decision aids and shared decision making [31,32,33]. Researchers increasingly regard the environmental scan as the strongest method of assessing the landscape of available patient decision aids [31,32,33]. With broader reach and inclusion criteria than systematic reviews, the environmental scan yields a more complete picture of the patient decision aids available for patient use, whether developed by academic researchers or private organizations [31,32,33]. In contrast, systematic reviews usually only include patient decision aids evaluated in published academic literature or gray literature. And although systematic reviews are well-established for answering questions about intervention effectiveness, they are less useful for answering questions like ours [34]. The Dartmouth College Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects reviewed this study protocol and declared this research exempt from further review.

3.1 Patient Decision Aid Identification

We will search for patient decision aids among published systematic reviews, Internet search results (Google.com), and app stores (Google Play and iTunes) [33]. We will also survey key informants [33]. Our search will be English language only, although we will include non-English patient decision aids that we discover. We detail our search concepts in Fig. 1.

Two reviewers (CHS and M-AD) will perform the screening [33]. The primary reviewer (CHS) will systematically screen all three data sources to identify patient decision aids: published reviews, online search results, and app store search results, and key-informant outreach and survey results [33]. Decision aids will be included in this scan if they meet the National Quality Forum’s screening criteria, which we adapted slightly for this study (see Table 1). The second reviewer (M-AD) will review 10% of data from all three sources to determine whether the patient decision aids included match those of the primary reviewer [33]. Inter-rater agreement will be calculated using Cohen’s kappa [35]. If the second reviewer uncovers significant disagreement, she will review 100% of the data. The reviewers will resolve all disputes through conversation and will involve a third researcher if they cannot reach consensus. After we identify all patient decision aids, two reviewers (CHS and M-AD) will review each patient decision aid and perform an assessment of whether the patient decision aid meets our inclusion criteria for life-sustaining treatments, i.e., it is appropriate or targeted at patients, who are seriously or critically ill [36]. We will conduct this exercise for every patient decision aid and calculate a Cohen’s kappa for inter-rater reliability. We added this second inclusion check because of the difficulty involved in identifying which patient decision aids address proximal decision making.

3.1.1 Published Systematic Reviews

Using a search strategy developed with a librarian (see Fig. 1), we will identify published systematic reviews of patient decision aids for life-sustaining treatments using the MEDLINE database (see Table 2). The primary reviewer (CHS) will examine the results of the MEDLINE search identifying reviews, including patient decision aids eligible for our study. Decision aids will then be extracted using a data collection form (see Table 3). Additionally, we will add the first authors of the systematic reviews to our informant contact list. We will archive all results that the queries of the academic databases yield [33]. We will download articles that mention patient decision aids in the abstracts for full-text review.

Using Google Advanced Search, we will run the queries detailed in Table 4. We will disable cookies and limit our search to English [33]. The primary reviewer will run each Google search, archiving the first 100 results [33]. This record will include web addresses, page titles, and other relevant details [37]. The primary reviewer will subsequently review the results, indicating which could potentially contain references to patient decision aids [33]. Given online content changes, the reviewer will also open each relevant page and archive it [33]. If any pages reference patient decision aids, we will attempt to find them [33]. We will also classify all patient decision aids as eligible or ineligible for inclusion in the study, using the patient decision aid definition detailed in Table 1. If discovered patient decision aids are unavailable online, we will contact stakeholders to inquire about them [33]. The team will document all reasons for exclusion [33].

We will follow a similar procedure as we search for applications, using the search terms to identify the first 50 results for both the Apple App Store and Google Play [33]. After recording all results and archiving descriptions, we will download potentially relevant apps for further review [33]. Again, reasons for exclusion will be noted [33].

3.1.2 Key Informant Survey

We will also conduct key-informant outreach in two parts. First, we will attempt to identify decision aids that do not appear in our Internet search and identify those that were mentioned but not available online. To do this, we will contact individuals or organizations that we have identified as using, developing, or studying specific Internet and app store patient decision aids through our Internet search, emailing them to request access.

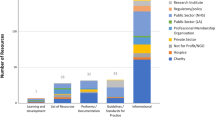

Second, we will simultaneously distribute a survey to 187 organizations and individuals that work in or study issues related to aging, death, or dying, or shared decision making and might be aware of patient decision aids for life-sustaining treatments. We identified these contacts through existing contacts and networks and the inventory of patient decision aid developers recently published by our research group [38]. We will deploy the survey using Qualtrics, an online survey software (see Appendix in the Electronic Supplementary Material). The questionnaire will address awareness of patient decision aids of life-sustaining treatments and knowledge of healthcare organizations that use the patient decision aids. We will request, review, and save decision aids suggested by informants. Additionally, we will use a snowball approach, asking sources if they are aware of other individuals or organizations we should contact [39]. When survey respondents recommend that we reach out to stakeholders, we will schedule calls or reach out to these people via email.

3.2 Data Abstraction and Analysis

3.2.1 Inclusion Criteria

For inclusion in our study, tools must be patient decision aids that help seriously ill patients and their families make decisions about life-sustaining treatments.

3.2.2 Decision Aid Criteria

Concerning meeting our decision aid criteria, for the purpose of this review, we will define decision aids using the draft National Quality Forum standards for screening patient decision aids [40]. The National Quality Forum uses the Cochrane Collaborative definition of patient decision aids: “an evidence-based tool designed to help patients to participate in making specific, deliberate choices among health care options” [23, 40]. The National Quality Forum screening criteria are broader than the commonly used International Patient Decision Aid Standards, thus using this approach will be more inclusive, furthering our aim of developing a comprehensive inventory [40, 41]. The National Quality Forum also recently updated their standards, meaning they are more current than International Patient Decision Aid Standards [40, 41]. Notably, some tools that do not qualify as patient decision aids using International Patient Decision Aid Standards, qualify as patient decision aids using the draft National Quality Forum criteria [40, 41]. Decision aids that are available either online or in print will be eligible for inclusion in our study; this may include commercially available decision aids, publicly accessible decision aids, or proprietary decision aids.

3.2.3 Index Decision Criteria

Concerning serious illness, we will consider any decision aids for choices about devices or procedures that sustain organ function. This may include but is not limited to cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ventilation, heart assist devices (left ventricular assist device), renal dialysis, artificial hydration or nutrition, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Patient decision aids intended for patients with specific diseases or characteristics will be eligible for inclusion. We will, however, exclude patient decision aids designed exclusively for children.

3.2.4 Serious Illness Criteria

Most advance directive forms will not qualify for inclusion in our review because they do not cater to individuals who are imminently facing decisions about life-sustaining treatments. In 2010, Warren and colleagues described preference construction as an acknowledgment that preferences are context sensitive and people determine preferences at the time of decision making [18]. We will adhere to this dual definition of preference construction, ensuring the patient decision aids we include are appropriate for proximal life-sustaining treatment decisions [18]. Specifically, that means we will include only patient decision aids that explicitly identify individuals who are seriously or critically ill as target users or offer outcome information tailored specifically at this group. We define serious illness as “a health condition that carries a high risk of mortality and either negatively impacts a person’s daily function or quality of life, or excessively burdens their caregivers” [36]. The seriously ill are the group typically targeted by palliative services for conversations about the risk of death and options because people nearing death cannot be predicted with precision ahead of the event [42]. These criteria disqualify many advance directives often used well in advance of serious decisions [4].

3.2.5 Data Abstraction

After we have identified all the patient decision aids that meet the inclusion criteria, we will collect information on each. See Table 3 for the data collection form. The data collection form will capture descriptions of the decision aids, developer information, index decisions, specific patient populations, the availability of the patient decision aid, and any information about patient decision aid use.

3.3 Patient Decision Aid Assessment

3.3.1 Quality Assessment

Two reviewers (CHS and KP) will independently assess the quality of each patient decision aid, using the draft National Standards for the Certification of patient decision aids from the National Quality Forum. There are 13 recommended certifying criteria for patient decision aid certification [40]. We will only be including criteria that are applicable to the patient decision aids themselves, not any supplementary materials, as we do not anticipating having access to all supplementary materials. We included detailed information concerning the plan for evaluating each quality measure in Table 1. We will calculate inter-rater reliability using Cohen’s Kappa [35].

3.3.2 Content Review

The reviewers will report themes in patient decision aid content using an inductive analysis approach [43]. We will pay particular attention to objective vs. subjective; and directive vs. nondirective language [33]. After we have coded all content, we will meet to identify themes [44]. For analysis, the reviewers will meet weekly to discuss patterns in content coding [44]. A second reviewer (M-AD) will review a 10% sample of the patient decision aids to confirm agreement with theme identification. Concurrently, we are exploring the development of a natural language processing program for rating the objectivity and subjectivity of patient decision aids, and we will analyze the results of this scan using that technique as well [45].

4 Anticipated Outcomes

The primary result of this study will be an inventory of life-sustaining treatment patient decision aids for patients and their clinicians, along with information on the quality and use. We anticipate that we will find 50 decision aids, created by both academic researchers and non-academic developers, based on our preliminary data screening. As a part of this outcome, we will assess the quality of each decision aid and characterize the content of the patient decision aids.

Our secondary outcome is a set of recommendations of opportunities for the future development or improvement of existing decision aids. Additionally, we anticipate we will further demonstrate the appropriateness of the environmental scan methodology for uncovering the landscape of available patient decision aids, by finding many tools outside of the published literature.

5 Discussion

This study will (1) identify and assess available patient decision aids for life-sustaining treatments. Subsequent studies will (2) explore barriers and facilitators to patient decision aid use by patients and families in hospitals, and (3) clarify the extent to which these patient decision aids are used in inpatient settings.

Producing a comprehensive inventory of decision aids for patients and families facing difficult decisions about life-sustaining care will be a valuable resource and novel contribution to the field. We intend to publish this inventory on a publicly available website, where patients, families, and clinical care teams can access the decision aids and make decisions about which decision aids are appropriate for their individual needs. We intend to make this resource available for 3 years. We will also publicize this resource in consumer-facing media. This approach will give patients and families, along with their care teams, a sense of the characteristics and quality of the decision aids they choose to explore.

Beyond the patient and clinical benefits, this work will help the research community. Characterizing the landscape of available life-sustaining treatment patient decision aids will give us an opportunity to recognize the advantages and deficits of the current approach to decision aid development. We hope to recommend improvements to both academic and non-academic developers of patient decision aids based on our findings. Many previous examinations of patient decision aids for life-sustaining treatments have focused on specific disease states. Our broader approach will provide an overview of this field across disease areas.

A strength of this study is that it will provide a real-world picture of life-sustaining treatment patient decision aids available to patients, their families, and their clinicians, which currently does not exist. Systematic reviews often assess only small numbers of available decision aids, only those that researchers have formally evaluated [46]. In contrast, our study will attempt to produce a comprehensive inventory of patient decision aids available to patients facing life-sustaining treatment decisions. Similarly, our snowball sampling of key-informants approach increases the likelihood that we will reach out to all relevant patient decision aid developers and other stakeholders [39].

Our approach also has limitations. For instance, although we are trying to inventory all available decision aids in the English language for life-sustaining treatment decisions, we may miss some. For feasibility reasons, we limited our search to English-language search engines, thus our resulting inventory of instruments may consequently miss important foreign-language patient decision aids.

6 Conclusion

The proposed environmental scan will provide the broadest view yet of the patient decision aids available to patients and families for life-sustaining treatment choices. Additionally, the method is unique for examining the real-world tools available to patients and families facing life-sustaining treatment decisions.

References

Goodman D, Fisher E. The Dartmouth atlas of health care. 2013. http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/. Accessed 18 Jul 2017.

AARP Bulletin Poll. “Getting ready to go” executive summary. Washington, DC: AARP; 2008.

Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G. Stop the silent misdiagnosis: patients’ preferences matter. BMJ. 2012;345:e6572.

Butler M, Ratner E, McCreedy E, Shippee N, Kane RL. Decision aids for advance care planning: an overview of the state of the science. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:408–18.

California HealthCare Foundation. Snapshot final chapter: Californians’ attitudes and experiences with death and dying. Oakland (CA): California Healthcare Foundation. 2012. http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA LIBRARY Files/PDF/PDF F/PDF FinalChapterDeathDying.pdf. Accessed 18 Jul 2017.

Heyland DK, Cook DJ, Rocker GM, Dodek PM, Kutsogiannis DJ, Peters S, et al. Decision-making in the ICU: perspectives of the substitute decision-maker. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:75–82.

Nelson JE, Danis M. End-of-life care in the intensive care unit: where are we now? Crit Care Med. 2001;29(2 Suppl):N2–9.

Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, Grambow S, Parker J, et al. Preparing for the end of life: preferences of patients, families, physicians, and other care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:727–37.

Tarver T. Older Americans 2012: key indicators of well-being. J Consum Health Internet. 2013;17(1):114–5. doi:10.1080/15398285.2013.756760.

Applebaum AJ, Kolva EA, Kulikowski JR, Jacobs JD, DeRosa A, Lichtenthal WG, et al. Conceptualizing prognostic awareness in advanced cancer: a systematic review. J Health Psychol. 2014;19:1103–19.

McCabe MS, Storm C. When doctors and patients disagree about medical futility. J Oncol Pract. 2008;4:207–9.

Samora J, Saunders L, Larson RF. Medical vocabulary knowledge among hospital patients. J Health Hum Behav. 1961;2:83.

Boyle CM. Difference between patients’ and doctors’ interpretation of some common medical terms. BMJ. 1970;2:286–9.

Peckham TJ. Doctor, have I got a fracture or a break? Injury. 1994;25:221–2.

Tuller D. Aging and health: medicare coverage for advance care planning: just the first step. Health Aff. 2016;35:390–3.

Medicare Learning Network. Advance Care Planning [Internet]. 2016. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/AdvanceCarePlanning.pdf. Accessed 22 Feb 2017.

The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. 10 FAQs: Medicare’s role in end-of-life care. 2017. http://kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/10-faqs-medicares-role-in-end-of-life-care/. Accessed 18 Jul 2017.

Warren C, Mcgraw AP, Van Boven L. Values and preferences: defining preference construction. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci. 2011;2:193–205.

Volandes A. Medicine grand rounds: Dartmouth Hitchcock. Lebanon (NH); 2015.

Elwyn G, Laitner S, Coulter A, Walker E, Watson P, Thomson R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS. BMJ. 2010;341:c5146.

Curtis JR, Patrick DL. Barriers to communication about end-of-life care in AIDS patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:736–41.

Elwyn G, Frosch D, Volandes AE, Edwards A, Montori VM. Investing in deliberation: a definition and classification of decision support interventions for people facing difficult health decisions. Med Decis Mak. 2010;30:701–11.

Stacey D, Legare F, Lewis K, Barry MJ, Bennett CL, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD001431.

El-Jawahri A, Mitchell SL, Paasche-Orlow MK, Temel JS, Jackson VA, Rutledge RR, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a CPR and intubation video decision support tool for hospitalized patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:1071–80.

Volandes AE, Ferguson LA, Davis AD, Hull NC, Green MJ, Chang Y, et al. Assessing end-of-life preferences for advanced dementia in rural patients using an educational video: a randomized controlled trial. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:169–77.

Song MK, Ward SE, Fine JP, Hanson LC, Lin FC, Hladik GA, et al. Advance care planning and end-of-life decision making in dialysis: a randomized controlled trial targeting patients and their surrogates. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66:813–22.

Brom L, De Snoo-Trimp JC, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Widdershoven GAM, Stiggelbout AM, Pasman HRW. Challenges in shared decision making in advanced cancer care: a qualitative longitudinal observational and interview study. Health Expect. 2017;20:69–84.

El-Jawahri A, Paasche-Orlow MK, Matlock D, Stevenson LW, Lewis EF, Stewart G, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of an advance care planning video decision support tool for patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation. 2016;134:52–60.

van den Akker M, Buntinx F, Roos S, Knottnerus JA. Problems in determining occurrence rates of multimorbidity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:675–9.

Fortin M, Bravo G, Hudon C, Vanasse A, Lapointe L. Prevalence of multimorbidity among adults seen in family practice. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:223–8.

Aslakson RA, Schuster ALR, Miller J, Weiss M, Volandes AE, Bridges JFP. An environmental scan of advance care planning decision AIDS for patients undergoing major surgery: a study protocol. Patient. 2014;7:207–17.

Legare F, Politi MC, Drolet R, Desroches S, Stacey D, Bekker H. Training health professionals in shared decision-making: an international environmental scan. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88:159–69.

Donnelly KZ, Thompson R. Medical versus surgical methods of early abortion: protocol for a systematic review and environmental scan of patient decision aids. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007966.

Grimshaw J. A guide to knowledge synthesis [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2017 Jul 28]. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/41382.html

Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The equivalence of weighted Kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measures of reliability. Educ Psychol Meas. 1973;33:613–9.

Kelley A. Identifying the population with serious illness: the “denominator” problem. J Palliat Med. (accepted)

Tsulukidze M, Grande SW, Thompson R, Rudd K, Elwyn G. Patients covertly recording clinical encounters: threat or opportunity? A qualitative analysis of online texts. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0125824.

Elwyn G, Dannenberg M, Blaine A, Poddar U, Durand M-A. Trustworthy patient decision aids: a qualitative analysis addressing the risk of competing interests. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e012562.

Atkinson R, Flint J. Accessing hard to reach populations for research: snowball research strategies. Soc Res Updat. 2001;33:1–4.

National Quality Forum. National Standards for the Certification of Patient Decision Aids. Washington, D.C.: National Quality Forum; 2016.

IPDAS 2005. International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration. Table 3: IPDAS Patient Decision Aid Checklist for Users; 2005.

Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy SM, Shugarman LR, Wilkinson A, Mularski RA, et al. Evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:147.

Pope C, Mays N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311:42–5.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88.

Chowdhury GG. Natural language processing. Annu Rev Inf Sci Technol. 2005;37:51–89.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Altman D. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Pamela Bagley for her support in the development of the online and app store search strategy. They also thank Lisa Sharp-Grady for her assistance in manuscript preparation. Additionally, they acknowledge Khusbu Patel who will assist with the decision aid quality review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.H. Saunders planned and designed the study. M.-A. Durand, G. Elwyn, and K.B. Kirkland provided advice and guidance on the design. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and approved the final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No funding was received for the preparation of this article.

Conflict of interest

Glyn Elwyn is the founder of the Option Grid Collaborative and Consultant for Emmi Solutions LLC, developer of patient decision support materials, and a consultant for EBSCO Health. Marie-Anne Durand is involved in developing and disseminating patient decision aids as part of the Option Grid Collaborative, and a consultant for EBSCO Health. Catherine H. Saunders and Kathryn K. Kirkland have no conflicts of interest directly relevant to the content of this article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Saunders, C.H., Elwyn, G., Kirkland, K. et al. Serious Choices: A Protocol for an Environmental Scan of Patient Decision Aids for Seriously Ill People at Risk of Death Facing Choices about Life-Sustaining Treatments. Patient 11, 97–106 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-017-0268-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-017-0268-2