Abstract

Background and Objectives

This qualitative interview study was designed to highlight the symptoms and functional limitations experienced by patients in the year following a myocardial infarction (MI). This information can support the use or development of patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments in the post-MI population.

Methods

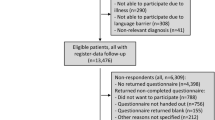

Individual face-to-face interviews were conducted with 38 participants who had experienced an MI (with or without ST segment elevation) within the past month to <6 months (n = 17), or 6 months to ≤12 months (n = 21). Using content and thematic analysis, patient reports of symptoms and functional limitations were coded and then grouped into categories. The specific content and frequency of the symptom and functional limitation reports were summarized.

Results

Nearly half of all symptom expressions were related to fatigue. Within this fatigue category, patients reported experiencing general tiredness, as well as a loss of physical energy, mental energy, and/or motivation. Chest pain and discomfort, sleep disruption, and shortness of breath were also frequently reported. Additionally, patients reported emotional effects, including worry and depression, as well as a negative impact on relationships and social activities.

Conclusions

Patients reported a wide variety of symptoms and functional limitations after an MI. Fatigue was the most commonly reported symptom and included several specific dimensions related to tiredness. Consideration of these concepts associated with the patient’s experience following an MI may yield novel endpoints for use in clinical trials and better therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sullivan PW, Lawrence WF, Ghushchyan V. A national catalog of preference-based scores for chronic conditions in the United States. Med Care. 2005;43:736–49.

Fredriksson-Larsson U, Alsen P, Karlson BW, Brink E. Fatigue two months after myocardial infarction and its relationship with other concurrent symptoms, sleep quality, an coping strategies. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:2192–200.

Brink E, Karlson BW, Hallberg LRM. Health experiences of first-time myocardial infarction: factors influencing women’s and men’s health-related quality of life after 5 months. Psychol Health Med. 2002;7(1):5–16.

Crane PB. Fatigue and physical activity in older women after myocardial infarction. Heart Lung. 2005;34:30–8.

Maddox TM, Reid KJ, Spertus JA, et al. Angina at 1 year after myocardial infarction. Prevalence and associated findings. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(12):1310–6.

Andersson EK, Borglin G, Willman A. The experience of younger adults following myocardial infarction. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(6):762–72.

Arnold LM, Wang F, Ahl L, et al. Improvement in multiple dimensions of fatigue in patients with fibromyalgia treated with duloxetine: secondary analysis of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis ResTher. 2011;13(3):R86.

Brink E, Brändström Y, Cliffordsson C, et al. Illness consequences after myocardial infarction: problems with physical functioning and return to work. J Adv Nurs. 2008;64(6):587–94.

Kruse M, Sorensen J, Davidsen M, et al. Short and long-term labour market consequences of coronary heart disease: a register-based follow up study. Eur Soc Cardiol. 2009;16:387–91.

Coyle MK. Over time: reflections after a myocardial infarction. Holist Nurs Pract. 2009;23:49–56.

Whooley MA, deJonge P, Vittinghoff E. Depressive symptoms, health behaviors, and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2008;300(20):2379–88.

US FDA. Guidance for industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling. US FDA; 2009.

Patrick D, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity-establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force Report. Part 1: eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health. 2011;14:967–77.

Sjostrom-Strand A, Ivarsson B, Sjoberg T. Women’s experience of a myocardial infarction: 5 years later. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25:459–66.

Johansson A, Dahlberg K, Ekebergh M. Living with experiences following a myocardial infarction. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2003;2:229–36.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

Maxwell JA. Using numbers in qualitative research. Qual Inq. 2010;16:475–82.

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough: an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18:59–82.

Larsen KK, Agerbo E, Christensen B, Sondergaard J, Vestergaard M. Myocardial infarction and risk of suicide: a population-based case-control study. Circulation. 2010;122(23):2388–93.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. MI-secondary prevention: secondary prevention in primary and secondary care for patients following a myocardial infarction. NICE clinical guideline 172. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2013.

Smith SC, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, Braun LT, Creager MA, Franklin BA, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2011;124(22):2458–73.

Langvik E, Hjemdal O. Symptoms of depression and anxiety before and after myocardial infarction: the HUNT 2 and HUNT 3 study. Psychol Health Med. 2015;20(5):560–9.

Ridker PM, Thuren T, Zalewski A, et al. Interleukin-1β inhibition and the prevention of recurrent cardiovascular events: rationale and design of the Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study (CANTOS). Am Heart J. 2011;162:597–605.

Lewis EF, Li Y, Pfeffer MA, et al. Impact of cardiovascular events on change in quality of life and utilities in patients after myocardial infarction: a VALIANT study (Valsartan In Acute Myocardial Infarction). JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2(2):159–65.

Ridker PM, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, Hennekens CH. Plasma concentration of interleukin-6 and the risk of future myocardial infarction among apparently healthy men. Circulation. 2000;101(15):1767–72.

Appels A, Bar FW, Bar J, Bruggeman C, de Baets M. Inflammation, depressive symptomtology, and coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(5):601–5.

Crane PB. Allen J. CVD risk reduction: the fountain of youth? Abstract 3017: physiological factors associated with fatigue in older adults after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116(Suppl 16):II-675–6.

Janszky I, Lekander M, Blom M, Georgiades A, Ahnve S. Self-rated health and vital exhaustion, but not depression, is related to inflammation in women with coronary heart disease. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19(6):555–63.

Kwaijtaal M, van Diest R, Bär FW, van der Ven AJ, Bruggeman CA, de Baets MH, et al. Inflammatory markers predict late cardiac events in patients who are exhausted after percutaneous coronary intervention. Atherosclerosis. 2005;182(2):341–8.

Bower JE, Lamkin DM. Inflammation and cancer-related fatigue: mechanisms, contributing factors, and treatment implications. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30(Suppl):S48–57.

Al-shair K, Kolsum U, Dockry R, Morris J, Singh D, Vestbo J. Biomarkers of systemic inflammation and depression and fatigue in moderate clinically stable COPD. Respir Res. 2011;12(1):3.

Gold SM, Irwin MR. Depression and immunity: inflammation and depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009;29(2):309–20.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lorie Scrabis for managing the operational aspects of the study, and Carla Ascoytia for her efforts in conducting the patient interviews.

Author contributions

Chad Gwaltney, Meaghan Krohe, Mona Martin, and Heather Falvey contributed to the study conception and design. Mona Martin was also involved in the collection of data. All authors were involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data, as well as drafting and critical revision of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Essex Institutional Research Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of interest

Chad Gwaltney, Matthew Reaney, Meaghan Krohe, and Mona Martin received consulting fees from Novartis Pharma AG for the completion of this work. Patrick Mollon holds stock from Pfizer Inc. and Novartis Pharma AG. Heather Falvey reports no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This study was funded by Novartis Pharma AG.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gwaltney, C., Reaney, M., Krohe, M. et al. Symptoms and Functional Limitations in the First Year Following a Myocardial Infarction: A Qualitative Study. Patient 10, 225–235 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-016-0194-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-016-0194-8