Abstract

Background

Morning hypertension is a risk factor for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events, and consequently diagnosis and control of morning hypertension are considered very important. We previously reported the results of the Azelnidipine Treatment for Hypertension Open-label Monitoring in the Early morning (At-HOME) Study, which indicated that azelnidipine effectively controlled morning hypertension.

Objectives

The objective of this At-HOME subgroup analysis was to evaluate the sustained blood pressure (BP)-lowering effect of azelnidipine, using mean morning and evening systolic BP [ME average] and morning systolic BP minus evening systolic BP (ME difference).

Methods

We analyzed the self-measured home BP data (measured in the morning and at bedtime) from this 16-week prospective observational study to clarify the effect of morning dosing of azelnidipine (mean [± standard deviation] maximum dose 14.3 ± 3.6 mg/day). A subgroup of patients from the At-HOME Study who had an evening home BP measurement within 28 days prior to the baseline date were used for efficacy analysis (n = 2,546; mean age, 65.1 years; female, 53.6 %).

Results

Home systolic BP/diastolic BP levels in the morning and evening were significantly lowered (p < 0.0001) by −19.4 ± 17.1/−10.3 ± 10.6 and −16.9 ± 17.0/−9.4 ± 10.6 mmHg, respectively. Home pulse rates in the morning and evening were also significantly lowered (p < 0.0001) by −3.5 ± 7.8 and −3.5 ± 7.3 beats/min, respectively. At baseline, patients whose ME average was ≥135 mmHg and whose ME difference was ≥15 mmHg (defined as morning-predominant hypertension) accounted for 20.4 % of the study population. However, at the end of the study, the number of such patients was significantly reduced to 7.9 % (p < 0.0001). Patients whose ME average was ≥135 mmHg and whose ME difference was <15 mmHg (defined as sustained hypertension) accounted for 71.1 % of the study population at baseline. This was reduced significantly to 42.8 % at the end of the study (p < 0.0001). ME average decreased significantly from 153.8 ± 15.5 mmHg to 135.6 ± 11.9 mmHg, and ME difference also decreased significantly from 6.7 ± 13.1 mmHg to 4.7 ± 10.8 mmHg (both p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

These results suggest that azelnidipine improved morning hypertension with its sustained BP-lowering effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Blood pressure (BP) fluctuates daily in a circadian pattern, i.e., it is elevated from evening to morning, and the frequency of myocardial infarction or stroke is also increased during the same period [1, 2]. Morning BP correlates with cardiovascular events, and therefore morning hypertension during the high-risk hours is very important [3–5]. Organ damage is related more to morning hypertension than to hypertension defined on the basis of measurement of BP at the clinic (clinic BP) [6]. Morning hypertension has been reported to be associated with an increased risk of future stroke [4, 7].

Although there is no consensus definition of morning hypertension, one practical definition is BP of 135/85 mmHg or higher measured at home in the morning (morning home BP) [8]. In the Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring (ABPM) Study [7], subjects were classified using the following thresholds: (i) an average of morning and evening systolic BP [ME average] of 135 mmHg; and (ii) a difference between morning and evening systolic BP (ME difference) of 20 mmHg; the relative risk of stroke was compared in the resulting four groups of subjects with normal BP, normal BP with a morning BP surge pattern, sustained hypertension, and morning-predominant hypertension. The risks of stroke were 2.1 and 6.6 times higher in the sustained hypertension and morning-predominant hypertension groups, respectively, than in the normal BP group. The stroke risk increased by 41 % with a 10 mmHg increase in ME average and by 24 % with a 10 mmHg increase in ME difference. Given that other cardiovascular risks also increase in the morning, the diagnosis of morning hypertension and control of BP have tremendous significance.

In the practical treatment of morning hypertension, it is ideal to combine the nonspecific approach of lowering ME average of home BP and the specific approach of reducing greater than threshold ME differences, leading the vector of BP lowering to normal BP limits [5].

Azelnidipine is a dihydropyridine calcium antagonist, which was synthesized by Ube Industries, Ltd. and developed by Sankyo Co., Ltd. (now known as Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). This agent has a potent and sustained BP-lowering effect in various animal models of hypertension [9]. It has also been confirmed to have renoprotective effects (such as reducing proteinuria by dilating efferent arterioles), as well as cardioprotective, insulin resistance-improving, cerebroprotective, and anti-atherosclerotic effects [10, 11].

In this study using the results from our previously reported special survey of azelnidipine (the Azelnidipine Treatment for Hypertension Open-label Monitoring in the Early morning [At-HOME] Study [12]), we performed subgroup analyses in cases with measurements of BP at home in the evening (evening home BP), to evaluate the effects of the agent on morning and evening home BP, using mainly ME average and ME difference as measures.

2 Subjects and Methods

2.1 Subjects

The At-HOME study [12] was conducted according to Article 14-4 (re-examination) of the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act, Japan, and in compliance with Good Post-marketing Study Practice (GPSP). For a list of participating medical centers [in Japanese], see the electronic supplementary material. The study included patients who met all of the following requirements at baseline when they started taking the study drug, azelnidipine (Calblock® tablets; Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd.): (i) outpatient with hypertension; (ii) no previous use of the study drug; (iii) clinic BP measurement within 28 days prior to baseline; and (iv) morning home BP measurement using an electronic brachial-cuff device at least two times on separate dates within 28 days prior to baseline. The study was conducted using the central enrollment method, in which patients from contracted medical institutions nationwide were registered by the enrollment center within 14 days after the baseline date. The enrollment period was one year from May 2006, and the planned number of cases to be investigated was 5,000.

From among the patients who were included in the primary analysis of the At-HOME Study [12], cases with evening home BP measurements within 28 days prior to the baseline date are described in this article.

The study drug was administered at the investigator’s discretion, according to the dosage and administration instructions in the package insert, with no limit set on dose increases or decreases, or on pretreatment or concomitant use of antihypertensive drugs. The standard observation period was 16 weeks, during which the study drug was administered, except in cases of withdrawal or dropout.

2.2 Outcome Measures

We investigated the patient characteristics, study drug dosage, study drug compliance, pretreatment with antihypertensive drugs, use of concomitant drugs, clinical course, clinical examinations, conditions of BP measurement at home, and adverse events occurring during or after treatment with the study drug. In order to investigate the variables under actual conditions, the method of BP measurement and the timing of dosing and BP measurement during the observation period were not specified in the study protocol, and these decisions were left to the investigators. Investigators assessed safety on the basis of the results of patient interviews and clinical examinations.

2.3 Subject Inclusion in Analysis Sets

The following enrolled patients were excluded from the safety analysis population: (i) those who reported no data from the investigation [non-respondents]; (ii) those who did not return to the clinic after the initial visit, precluding assessment of adverse events; (iii) those who took no study drug; (iv) those with no written description of adverse events; and (v) those who exceeded the timeframe for registration (ineligibility proven after data collection). From among the safety analysis population, the following patients were excluded from the efficacy analysis population: (i) those who were not outpatients with hypertension at baseline; (ii) those who had previously used the study drug; (iii) those with no clinic BP measurement within 28 days prior to the baseline date; (iv) those with no morning home BP measurement using an electronic brachial-cuff device within 28 days prior to the baseline date; and (v) those whose reported compliance was “[I] almost never take the study drug”. Although at least two morning home BP measurements on separate dates were required for enrollment in the study, patients with only one morning home BP measurement were also included in the study analyses. It was confirmed that there were no major differences in the results of the primary analysis when only those patients with two measurements of BP (protocol-compliant cases) were included. From among the safety and efficacy populations included in the primary analysis of the At-HOME Study [12], patients with no evening home BP measured within 28 days prior to the baseline date were excluded from the present study.

Patient classification according to morning and evening systolic blood pressure (ME average) and morning systolic blood pressure minus evening systolic blood pressure (ME difference) [5]. BP blood pressure

2.4 Methods of Analysis

The morning and evening home BP and pulse rates at weeks 4, 8, 12, and 16 of treatment were compared with those at baseline by Dunnett’s test. Changes from before to after azelnidipine treatment were analyzed using a paired t-test. Values were expressed as means ± standard deviations (SDs).

Figure 1 shows the patient classification system using ME average and ME difference as measures. The cut-off values of ME average and ME difference were 135 mmHg and 15 mmHg, respectively. Evaluation was carried out in the following four groups: those with normal BP (ME average of <135 mmHg and ME difference of <15 mmHg); those with normal BP with a morning BP surge pattern (ME average of <135 mmHg and ME difference of ≥15 mmHg); those with morning-predominant hypertension (ME average of ≥135 mmHg and ME difference of ≥15 mmHg); and those with sustained hypertension (ME average of ≥135 mmHg and ME difference of <15 mmHg). Changes in the patient distribution based on ME average and ME difference from before to after azelnidipine treatment were evaluated using the McNemar test. All tests were two-sided, with the significance level being set at p = 0.05.

Adverse events and adverse drug reactions were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA)/J version 11.0 and classified according to their Preferred Terms.

3 Results

3.1 Patient Disposition

Figure 2 shows the patient disposition. After exclusion of patients with no evening home BP measurement within 28 days prior to the baseline date, 2,590 and 2,546 patients were included in the safety and efficacy analysis populations, respectively.

3.2 Patient Characteristics

Table 1 shows the patient characteristics at baseline. The mean age was 65.1 ± 11.7 years, and 53.6 % of patients were female. The mean baseline home systolic BP (SBP)/diastolic BP (DBP) values were 156.9 ± 16.1/89.7 ± 11.7 mmHg in the morning and 150.2 ± 17.6/85.6 ± 12.2 mmHg in the evening. The mean pulse rates were 72.1 ± 10.2 beats/min in the morning and 72.5 ± 9.6 beats/min in the evening. During the observation period, morning home BP was usually measured before breakfast and before dosing in a large proportion (86.8 %) of cases.

3.3 Dosage of the Study Drug

Table 2 shows the dosage of the study drug. The most frequently used initial daily dose and maximal daily dose was 16 mg (in 66.5 % and 77.1 % of cases, respectively). The mean initial and maximal daily doses were 13.3 ± 3.9 mg and 14.3 ± 3.6 mg, respectively.

Table 3 details the concomitant drugs used by patients at baseline. Antihypertensive drugs other than the study drug were concomitantly used in 46.0 % of the patients; among those antihypertensive drugs, angiotensin II receptor blockers were those most frequently used (36.4 %).

3.4 Changes in Morning and Evening Home Blood Pressure and Pulse Rates

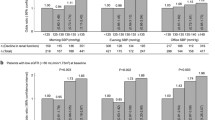

The mean values of the morning and evening home BP and pulse rates at each timepoint are shown in Fig. 3 and Table 4. The morning and evening home SBP, DBP, and pulse rates decreased significantly by week 4 as compared with baseline (p < 0.0001), and these improvements were maintained at 16 weeks (p < 0.0001).

Table 5 shows the mean values and changes in morning and evening home BP and pulse rates before and after treatment with the study drug. The morning and evening home SBP/DBP values decreased significantly (p < 0.0001), with the changes being −19.4 ± 17.1/−10.3 ± 10.6 and −16.9 ± 17.0/−9.4 ± 10.6 mmHg, respectively. Pulse rates also decreased significantly (p < 0.0001) both in the morning and in the evening, by −3.5 ± 7.8 and −3.5 ± 7.3 beats/min, respectively.

3.5 Changes in ME Average and ME Difference

The changes in ME average and ME difference after azelnidipine treatment are shown in Table 6. ME average decreased significantly from 153.8 ± 15.5 mmHg at baseline to 135.6 ± 11.9 mmHg at the end of the investigation (endpoint), with the change being −18.1 ± 15.6 mmHg (p < 0.0001). ME difference also decreased significantly from 6.7 ± 13.1 mmHg at baseline to 4.7 ± 10.8 mmHg at the endpoint, with the change being −2.5 ± 13.2 mmHg (p < 0.0001).

3.6 Changes in Patient Distribution Based on ME Average and ME Difference

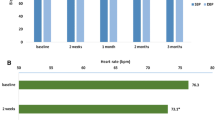

Table 7 and Fig. 4 show the changes in the distribution (based on ME average and ME difference) of 2,101 patients in whom both morning and evening home BP were measured before and after azelnidipine treatment. At baseline, 5.7 % (n = 120), 2.8 % (n = 58), 20.4 % (n = 429), and 71.1 % (n = 1,494) of patients were classified as having normal BP, normal BP with a morning BP surge pattern, morning-predominant hypertension, and sustained hypertension, respectively; at the endpoint, the corresponding values were 42.8 % (n = 899), 6.5 % (n = 136), 7.9 % (n = 166), and 42.8 % (n = 900), respectively. Of the patients with morning-predominant hypertension and sustained hypertension at baseline, 35.0 % and 42.6 %, respectively, were classified as having normal BP at the endpoint.

The proportion of patients with normal BP increased from 5.7 % to 42.8 % after treatment, which was higher than the 37.9 % value reported in the Jichi Morning Hypertension Research (J-MORE) Study [13] (Fig. 5). The proportion of patients who achieved ME average of <135 mmHg increased from 8.5 % to 49.3 %, and the proportion of those who achieved ME difference of <15 mmHg increased from 76.8 % to 85.6 %. The study treatment was associated with a significant improvement in the patient distribution based on ME average and ME difference (p < 0.0001).

Patient classification according to morning and evening systolic blood pressure (ME average) and morning systolic blood pressure minus evening systolic blood pressure (ME difference) in patients who received antihypertensive medication in the Jichi Morning-Hypertension Research (J-MORE) Study [13]. BP blood pressure

Scatter plots of the patient distribution based on ME average and ME difference before and after treatment are shown in Fig. 6. The study treatment was associated with an obvious tendency toward improvements in both ME average and ME difference.

Changes in patient distribution according to morning and evening systolic blood pressure (ME average) and morning systolic blood pressure minus evening systolic blood pressure (ME difference): a patient distribution at baseline (n = 2,546); b patient distribution at the study endpoint (n = 2,408). BP blood pressure

3.7 Safety

Table 8 shows adverse drug reactions reported in the safety analysis population, classified according to their MedDRA Preferred Terms. Adverse drug reactions occurred in 3.13 % of patients (81/2,590), and the incidences of adverse drug reactions commonly associated with calcium antagonists were 0.50 % for dizziness, 0.31 % for headache, 0.19 % for palpitations, 0.15 % for hot flushes, and 0.15 % for edema.

4 Discussion

Morning hypertension is a risk factor for cardiovascular events, especially stroke, which occur most frequently in the morning hours [1, 2]. The J-MORE Study reported that morning BP was poorly controlled in more than half of the patients whose clinic BP was controlled by antihypertensive treatment [13]. It is impossible to detect abnormal variation in BP (a manifestation associated with morning hypertension) by means of clinic BP measurements, and therefore it is clinically highly significant to appropriately diagnose and treat morning hypertension by making the most of home BP monitoring, which is widely used by hypertensive patients in Japan [14, 15]. In addition, home BP monitoring is useful for improving the compliance of patients and for evaluating the sustained BP-lowering effect of a drug.

In this investigation, we conducted subgroup analyses of data from the At-HOME Study [12] to evaluate the effects of azelnidipine on morning and evening home BP, using mainly ME average and ME difference as measures. The effect on home pulse rates was also evaluated.

All morning and evening home BP (SBP and DBP) values and pulse rates decreased significantly by week 4 as compared with baseline (p < 0.0001), and the significant BP-lowering effect lasted through week 16 (p < 0.0001). The changes also demonstrated the significant decreases in morning and evening home BP and pulse rates (p < 0.0001).

In the management of hypertension, the end result of treatment with antihypertensive drugs with insufficient sustained BP-lowering effects could be morning hypertension. As nearly half of hypertensive patients are those with morning hypertension, treatment targeting morning hypertension (as assessed by measuring ME average and ME difference) should be added to standard therapy [5].

Regarding the changes in patient distribution based on ME average and ME difference, in this investigation the proportion of patients classified as having normal BP increased significantly from 5.7 % to 42.8 %, which was higher than the value of 37.9 % reported in the J-MORE Study [13]. Of the patients with morning-predominant hypertension at baseline, 35.0 % were classified as having normal BP at the endpoint.

The proportion of patients who achieved ME average of <135 mmHg increased from 8.5 % to 49.3 % after azelnidipine treatment. The proportion of those who achieved ME difference of <15 mmHg also increased from 76.8 % to 85.6 %, which was higher than the value of 74.9 % reported in the J-MORE Study [13].

Scatter plots of the patient distribution based on ME average and ME difference before and after treatment also demonstrated that azelnidipine treatment was associated with an obvious tendency toward normalization of BP in terms of both ME average and ME difference.

It was inferred from these findings that azelnidipine suppresses the morning BP surge because its BP-lowering effect persists until the morning of the following day, i.e., for 24 h. The treatment of morning hypertension may include a combination of nonspecific and specific approaches, according to the morning BP levels [5]. In nonspecific treatment, long-acting antihypertensive drugs are used in principle, and the goal is to achieve an ME average of 135 mmHg or lower by using long-acting calcium antagonists or diuretics. On the other hand, in specific treatment, the goal is to decrease ME difference to 15–20 mmHg or lower by evening dosing with renin-angiotensin system inhibitors or α-blockers, or by using calcium antagonists, which have a pulse rate-lowering effect [5]. ME difference has been reported to correlate significantly with the left ventricular mass index in hypertensive patients who have never been treated for this condition or who have recently been treated with long-acting antihypertensive drugs, and it is thought to be an important risk factor for left ventricular hypertrophy [6, 16]. Azelnidipine, a long-acting calcium antagonist with a pulse rate-lowering effect, decreased ME average and ME difference significantly in the present study. On the basis of these findings, azelnidipine seems to be useful for treating morning hypertension by exerting the combined effects of specific and nonspecific treatment. In addition, this drug may be expected to improve left ventricular hypertrophy by decreasing ME difference.

At present, the most common therapy for hypertension is long-acting antihypertensive drugs given once daily. The use of long-acting once-daily formulations improves patient compliance. If BP lowering due to once-daily antihypertensive drugs fails to persist for 24 h, then morning hypertension—an important risk factor for cardiovascular events—could be poorly controlled. Azelnidipine has superior affinity for vascular tissues because it is more lipophilic than other calcium antagonists. The drug has been reported to distribute within vascular tissues, where its strong binding to L-type calcium channels by the ‘membrane approach’ may enhance its ability to exert a gradual, long-lasting, and potent BP-lowering effect [17, 18]. The results of the present investigation confirmed that the BP-lowering effect of azelnidipine persists for 24 h (i.e., until the morning of the following day) and decreases ME average and ME difference. Specifically, its effect of restoring BP to normal in patients with morning-predominant hypertension suggests that the drug is highly valuable for those patients with morning hypertension, who are at high risk of cardiovascular events [3–5], especially stroke [7].

5 Conclusion

Patients with evening home BP measurements, drawn from the primary analysis population of the special survey of azelnidipine (the At-HOME Study) conducted from May 2006 to September 2007, were included in the present subgroup analyses to evaluate the effects of the drug on morning and evening home BP values. The results were as follows:

-

1

Both home SBP and DBP measured in the morning and evening decreased significantly by week 4 of azelnidipine treatment, and the BP-lowering effect lasted through week 16. The changes from baseline in home SBP/DBP were −19.4 ± 17.1/−10.3 ± 10.6 mmHg in the morning and −16.9 ± 17.0/−9.4 ± 10.6 mmHg in the evening, demonstrating significant changes after treatment.

-

2

In the patient distribution based on ME average and ME difference at the study endpoint, the proportion of those classified as having normal BP was 42.8 %, which was higher than the value of 37.9 % reported in the J-MORE Study. Of the patients with morning-predominant hypertension and sustained hypertension at baseline, 35.0 % and 42.6 %, respectively, were classified as having normal BP at the study endpoint.

-

3

The proportion of patients who achieved an ME average of <135 mmHg increased to 49.3 % after azelnidipine treatment. The proportion of those who achieved an ME difference of <15 mmHg was 85.6 %.

On the basis of these findings, azelnidipine appears to have a BP-lowering effect that lasts well into the morning of the next day, and therefore it may be very useful for treating patients with morning hypertension, who are at high risk of cardiovascular events, especially stroke.

References

Muller JE, Tofler GH, Stone PH. Circadian variation and triggers of onset of acute cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 1989;79(4):733–43.

Kelly-Hayes M, Wolf PA, Kase CS, et al. Temporal patterns of stroke onset: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1995;26(8):1343–7.

Willich SN, Lewis M, Lowel H, et al. Physical exertion as a trigger of acute myocardial infarction. Triggers and Mechanisms of Myocardial Infarction Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(23):1684–90.

Asayama K, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, et al. Prediction of stroke by home “morning” versus “evening” blood pressure values: the Ohasama study. Hypertension. 2006;48(4):737–43.

Kario K. Clinician’s manual on early morning risk management in hypertension. London: Science Press; 2004. p. 1–68.

Shibuya Y, Ikeda T, Gomi T. Morning rise of blood pressure assessed by home blood pressure monitoring is associated with left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patients receiving long-term antihypertensive medication. Hypertens Res. 2007;30(10):908–11.

Kario K, Ishikawa J, Pickering TG, et al. Morning hypertension: the strongest independent risk factor for stroke in elderly hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res. 2006;29(8):581–7.

Ogihara T, Kikuchi K, Matsuoka H, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH2009). Hypertens Res. 2009;32(1):3–107.

Oizumi K, Nishino H, Koike H, et al. Antihypertensive effects of CS-905, a novel dihydropyridine Ca++ channel blocker, in SHR [in Japanese]. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1989;51:57–64.

Oizumi K, Nishino H, Miyamoto M, et al. Beneficial renal effects of CS-905, a novel dihydropyridine calcium blocker, in SHR [in Japanese]. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1989;51(4):501–8.

Ikeda K, Nishino H, Oizumi K, et al. Antihypertensive effects of CS-905, a new calcium antagonist, in cholesterol-fed rabbits [in Japanese]. Jpn J Pharmacol. 1992;58(Suppl):342.

Kario K, Sato Y, Shirayama M, et al. Inhibitory effects of azelnidipine (Calblock®) tablet on early-morning hypertension (At-HOME Study) [in Japanese]. J Clin Ther Med. 2008;24(12):1083–98.

Ishikawa J, Kario K, Hoshide S, et al. Determinants of exaggerated difference in morning and evening blood pressure measured by self-measured blood pressure monitoring in medicated hypertensive patients: Jichi Morning Hypertension Research (J-MORE) Study. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18(7):958–65.

Fukunaga E, Ohkubo T, Ohara T, et al. Current situation in home blood pressure measurement in Japan: practice and significance of 1,928 doctors. An investigation of the current situation in home blood pressure measurement [in Japanese]. J Blood Pressure. 2006;13:122–8.

Ohara T, Ohkubo T, Kikuya M, et al. Current situation in home blood pressure measurement in Japan: practice and significance in 8,506 outpatients [in Japanese]. An investigation of the current situation in home blood pressure measurement. J Blood Pressure. 2006;13:103–10.

Matsui Y, Eguchi K, Shibasake S, et al. Association between the morning–evening difference in home blood pressure and cardiac damage in untreated hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2009;27:712–20.

Sada T, Mizuno M, Miyama T, et al. Pharmacological characteristics of azelnidipine, a long-acting calcium antagonist, having vascular affinity (No. 2)—antihypertensive effect and pharmacokinetics in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) [in Japanese]. Jpn Pharmacol Ther. 2002;30(9):711–20.

Sada T, Mizuno M, Oohata K, et al. Antiatherosclerotic effect of azelnidipine, a long-acting calcium antagonist with high lipophilicity, in cholesterol-fed rabbits [in Japanese]. Jpn Pharmacol Ther. 2002;30(9):721–8.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the investigators who cooperated with the At-HOME Study and provided valuable data. The authors would also like to thank Rod McNab and Nila Bhana from inScience Communications, Springer Healthcare (Auckland, New Zealand), who provided English-language editing. This assistance, as well as the translation from Japanese to English, was funded by Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd (Tokyo, Japan). Kazuyuki Shimada is now employed by Oyama Municipal Hospital (Tochigi, Japan). Masahiro Komiya is now employed by Daiichi Sankyo Healthcare Co., Ltd (Tokyo, Japan). The authors have no other conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this article. A version of this manuscript was previously published in Japanese in the Journal of Clinical Therapeutics & Medicine [2009;25(3):281–96]. The publisher of the Journal of Clinical Therapeutics & Medicine has given permission for publication of this article in English.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kario, K., Uehara, Y., Shirayama, M. et al. Study of Sustained Blood Pressure-Lowering Effect of Azelnidipine Guided by Self-Measured Morning and Evening Home Blood Pressure: Subgroup Analysis of the At-HOME Study. Drugs R D 13, 75–85 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-013-0007-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40268-013-0007-7