Abstract

Background

The Canadian Emergency Team Initiative (CETI) cohort showed that minor injuries like sprained ankles or small fractures trigger a downward spiral of functional decline in 16% of independent seniors up to 6 months post-injury. Such seniors frequently receive medications with sedative or anticholinergic properties. The Drug Burden Index (DBI), which summarises the drug burden of these specific medications, has been associated with decreased physical and cognitive functioning in previous research.

Objectives

We aimed to assess the contribution of the DBI to functional decline in the CETI cohort.

Methods

CETI participants were assessed physically and cognitively at baseline during their consultations at emergency departments (EDs) for their injuries and up to 6 months thereafter. The medication data were used to calculate baseline DBI and functional status was measured with the Older Americans Resources and Services (OARS) scale. Multivariate linear regression models assessed the association between baseline DBI and functional status at 6 months, adjusting for age, sex, baseline OARS, frailty level, comorbidity count, and mild cognitive impairment.

Results

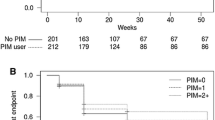

The mean age of the 846 participants was 77 years and their mean DBI at baseline was 0.24. Complete follow-up data at 3 or 6 months was available for 718 participants among whom a higher DBI at the time of injury contributed to a lower functional status at 6 months. Each additional point in the DBI lead to a loss of 0.5 points on the OARS functional scale, p < 0.001. Among those with a DBI ≥ 1, 27.4% were considered ‘patients who decline’ at 3 or 6 months’ follow-up, compared with 16.0% of those with a DBI of 0 (p = 0.06).

Conclusions

ED visits are considered missed opportunities for optimal care interventions in seniors; Identifying their DBI and adjusting treatment accordingly may help limit functional decline in those at risk after minor injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Drug use among seniors in Canada, 2016. Ottawa: CIHI; 2018.

Ruxton K, Woodman RJ, Mangoni AA. Drugs with anticholinergic effects and cognitive impairment, falls and all-cause mortality in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(2):209–20.

Hilmer SN, McLachlan AJ, Le Couteur DG. Clinical pharmacology in the geriatric patient. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2007;21(3):217–30.

Kashyap M, Belleville S, Mulsant BH, et al. Methodological challenges in determining longitudinal associations between anticholinergic drug use and incident cognitive decline. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(2):336–41.

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ. 2015;349:g7647.

Zulman DM, Sussman JB, Chen X, et al. Examining the evidence: a systematic review of the inclusion and analysis of older adults in randomized controlled trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(7):783–90.

Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294(6):716–24.

Mangoni AA, Jackson SH. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57(1):6–14.

Fulton MM, Allen ER. Polypharmacy in the elderly: a literature review. J Am Acad Nurse Practitioners. 2005;17(4):123–32.

Ganjavi H, Herrmann N, Rochon PA, et al. Adverse drug events in cognitively impaired elderly patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;23(6):395–400.

Cherubini A, Ruggiero C, Gasperini B, et al. The prevention of adverse drug reactions in older subjects. Curr Drug Metab. 2011;12(7):652–7.

Chumney EC, Robinson LC. The effects of pharmacist interventions on patients with polypharmacy. Pharm Pract. 2006;4(3):103–9.

Tamura BK, Bell CL, Inaba M, et al. Outcomes of polypharmacy in nursing home residents. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28(2):217–36.

Zed PJ, Abu-Laban RB, Balen RM, et al. Incidence, severity and preventability of medication-related visits to the emergency department: a prospective study. CMAJ. 2008;178(12):1563–9.

Ambrose AF, Paul G, Hausdorff JM. Risk factors for falls among older adults: a review of the literature. Maturitas. 2013;75(1):51–61.

Bennett A, Gnjidic D, Gillett M, et al. Prevalence and impact of fall-risk-increasing drugs, polypharmacy, and drug-drug interactions in robust versus frail hospitalised falls patients: a prospective cohort study. Drugs Aging. 2014;31(3):225–32.

Farrell B, Eisener-Parsche P, Dalton D. Turning over the rocks: role of anticholinergics and benzodiazepines in cognitive decline and falls. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60(4):345–50.

Fried TR, O’Leary J, Towle V, et al. Health outcomes associated with polypharmacy in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(12):2261–72.

Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):57–65.

Jano E, Aparasu RR. Healthcare outcomes associated with beers’ criteria: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(3):438–47.

Wennie Huang WN, Perera S, VanSwearingen J, et al. Performance measures predict onset of activity of daily living difficulty in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(5):844–52.

Lau DT, Briesacher BA, Touchette DR, et al. Medicare part D and quality of prescription medication use in older adults. Drugs Aging. 2011;28(10):797–807.

Peron EP, Gray SL, Hanlon JT. Medication use and functional status decline in older adults: a narrative review. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2011;9(6):378–91.

Gnjidic D, Bell JS, Hilmer SN, et al. Drug Burden Index associated with function in community-dwelling older people in Finland: a cross-sectional study. Ann Med. 2012;44:458–67.

Taipale HT, Bell JS, Gnjidic D, et al. Sedative load among community-dwelling people aged 75 years or older: association with balance and mobility. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(2):218–24.

Hilmer SN, Mager DE, Simonsick EM, et al. A drug burden index to define the functional burden of medications in older people. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(8):781–7.

Hilmer SN, Mager DE, Simonsick EM, et al. Drug burden index score and functional decline in older people. Am J Med. 2009;122(12):1142–1149.e1–2.

Gnjidic D, Cumming RG, Le Couteur DG, et al. Drug Burden Index and physical function in older Australian men. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68:97–105.

Cardwell K, Hughes CM, Ryan C. The association between anticholinergic medication burden and health related outcomes in the ‘oldest old’: a systematic review of the literature. Drugs Aging. 2015;32(10):835–48.

Tannenbaum C, Farrell B, Shaw J, et al. An ecological approach to reducing potentially inappropriate medication use: Canadian Deprescribing Network. Can J Aging. 2017;36(1):97–107.

Ioannidis G, Papaioannou A, Hopman WM, et al. Relation between fractures and mortality: results from the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. CMAJ. 2009;181(5):265–71.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Seniors’ use of emergency departments in Ontario, 2004–2005 to 2008–2009. Ottawa: CIHI; 2010.

Bawa H, Brussoni M, De Gagné D, et al. Emergency Department Surveillance System: Seniors injury data report 2001–2003. Vancouver: BC Injury Research and Prevention Unit; 2004.

Sirois MJ, Emond M, Ouellet MC, et al. Cumulative incidence of functional decline after minor injuries in previously independent older Canadian individuals in the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(10):1661–8.

Hoogerduijn JG, Schuurmans MJ, Duijnstee MS, et al. A systematic review of predictors and screening instruments to identify older hospitalized patients at risk for functional decline. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(1):46–57.

Williams M, Soiza R, Jenkinson AM, et al. Exercising with computers in later life (EXCELL)—pilot and feasibility study of the acceptability of the Nintendo™ WiiFit in community dwelling. Biomed Cent Res Notes. 2010;3(238):1–8.

Salvi F, Morichi VGA, Giorgi R, et al. The elderly in the emergency department: a critical review of problems and solutions. Intern Emerg Med. 2007;2:292–301.

Platts-Mills TF, Owens ST, McBride JM. A modern-day purgatory: older adults in the emergency department with nonoperative injuries. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(3):525–8.

Provencher V, Sirois MJ, Ouellet MC, et al. Decline in basic activities of daily living following visits to Canadian emergency department for minor injuries among independent seniors: Are frail older adults with cognitive impairments at greater risk? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(5):860–8.

Lee J, Sirois MJ, Moore L, et al. Return to the ED and hospitalisation following minor injuries among older persons treated in the emergency department: predictors among independent seniors within 6 months. Age Ageing. 2015;44(4):624–9.

Fillenbaum G. Multidimensional functional assessment: the OARS methodology—a manual. Durham: Center for the Study of Aging and Human development, Duke University; 1975. p. 134.

Agrément Canada, Institut canadien d’information sur la santé, Institut canadien pour la sécurité des patients, et al. Bilan comparatif des médicaments au Canada: hausser la barre—Progrès à ce jour et chemin à parcourir. Ottawa, ON: Agrément Canada; 2012. p. 24.

World Health Organization. WHO Collaborating Center for Drug Statistics Methodology. 2009 [Internet]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/whosis/data/Search.jsp.

Dispennette R, Elliott D, Nguyen L, et al. Drug Burden Index score and anticholinergic risk scale as predictors of readmission to the hospital. Consultant Pharm. 2014;29(3):158–68.

Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties, online version (e-CPS). © Canadian Pharmacists Association, 2014. Available from: https://www-e-therapeutics-ca.acces.bibl.ulaval.ca/legacy/cps.showMonograph.action.

Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. 37th edition [Internet]. The Pharmaceutical Press. MedicinesComplete © 2015. 2015. Available from: https://www-medicinescomplete-com.acces.bibl.ulaval.ca/mc/martindale/current/.

Gnjidic D, Hilmer SN, Hartikainen S, et al. Impact of high risk drug use on hospitalization and mortality in older people with and without Alzheimer’s disease: a national population cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e83224.

Haywood KL, Garratt AM, Fitzpatrick R. Quality of life in older people: a structured review of generic self-assessed health instruments. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(7):1651–68.

Haywood KL, Garratt AM, Fitzpatrick R. Older people specific health status and quality of life: a structured review of self-assessed instruments. J Eval Clin Pract. 2005;11(4):315–27.

McCusker J, Bellavance F, Cardin S, et al. Detection of older people at increased risk of adverse health outcomes after an emergency visit: the ISAR screening tool. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(10):1229–37.

Abdulaziz K, Perry JJ, Taljaard M, et al. National survey of geriatricians to define functional decline in elderly people with minor trauma. Can Geriatr J. 2016;19(1):2–8.

Ensrud KE, Ewing SK, Cawthon PM, et al. A comparison of frailty indexes for the prediction of falls, disability, fractures, and mortality in older men. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(3):492–8.

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005;173(5):489–95.

Canadian Study of Health and Aging Working Group. Canadian Study of Health and Aging: study methods and prevalence of dementia. CMAJ. 1994;150(6):899–913.

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–9.

Brandt J, Spencer M, Folstein M. The telephone interview for cognitive status. Cogn Behav Neurol. 1988;1(2):111–8.

Lacruz M, Emeny R, Bickel H, et al. Feasibility, internal consistency and covariates of TICS-m (telephone interview for cognitive status-modified) in a population-based sample: findings from the KORA-Age study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(9):971–8.

Knopman DS, Roberts RO, Geda YE, et al. Validation of the telephone interview for cognitive status-modified in subjects with normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment, or dementia. Neuroepidemiology. 2010;34(1):34–42.

Lee JY, Dong Woo L, Cho SJ, et al. Brief screening for mild cognitive impairment in elderly outpatient clinic: validation of the Korean version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2008;21(2):104–10.

Luis CA, Keegan AP, Mullan M. Cross validation of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment in community dwelling older adults residing in the Southeastern US. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(2):197–201.

Gallo JJ, Breitner JC. Alzheimer’s disease in the NAS-NRC Registry of aging twin veterans, IV. Performance characteristics of a two-stage telephone screening procedure for Alzheimer’s dementia. Psychol Med. 1995;25(6):1211–9.

Vercambre MN, Cuvelier H, Gayon YA, et al. Validation study of a French version of the modified telephone interview for cognitive status (F-TICS-m) in elderly women. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(11):1142–9.

Whitney SL, Marchetti GF, Schade A, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of the Timed “Up & Go” and the Dynamic Gait Index for self-reported falls in persons with vestibular disorders. J Vestib Res. 2004;14(5):397–409.

Tinetti M, Williams C. Falls, injuries due to falls, and the risk of admission to a nursing home. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(18):1279–84.

Ontario Injury Prevention Resource Center. Injuries among seniors in Ontario: a descriptive analysis of emergency department and hospitalization Data. Toronto: Ontario Injury Prevention Resource Centre; 2007.

Paniagua MA, Malphurs JE, Phelan EA. Older patients presenting to a county hospital ED after a fall: missed opportunities for prevention. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24(4):413–7.

Yardley L, Beyer N, Hauer K, et al. Development and initial validation of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I). Age Ageing. 2005;34(6):614.

Salahudeen MS, Chyou TY, Nishtala PS. Serum anticholinergic activity and cognitive and functional adverse outcomes in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the Literature. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0151084.

Salahudeen MS, Hilmer SN, Nishtala PS. Comparison of anticholinergic risk scales and associations with adverse health outcomes in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(1):85–90.

Wouters H, van der Meer H, Taxis K. Quantification of anticholinergic and sedative drug load with the Drug Burden Index: a review of outcomes and methodological quality of studies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73(3):257–66.

Melady D, Perry A. Ten best practices for the older patient in the emergency department. Clin Geriatr Med. 2018;34(3):313–26.

Tsunoda K, Uchida H, Suzuki T, et al. Effects of discontinuing benzodiazepine-derivative hypnotics on postural sway and cognitive functions in the elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(12):1259–65.

Curran HV, Collins R, Fletcher S, et al. Older adults and withdrawal from benzodiazepine hypnotics in general practice: effects on cognitive function, sleep, mood and quality of life. Psychol Med. 2003;33(7):1223–37.

Barker MJ, Greenwood KM, Jackson M, et al. Persistence of cognitive effects after withdrawal from long-term benzodiazepine use: a meta-analysis. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2004;19(3):437–54.

Salahudeen M, Duffull S, Nishtala P. Impact of anticholinergic discontinuation on cognitive outcomes in older people: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2014;31(3):185–92.

Kersten H, Molden E, Tolo IK, et al. Cognitive effects of reducing anticholinergic drug burden in a frail elderly population: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(3):271–8.

Boye NDA, van der Velde N, de Vries OJ, et al. Effectiveness of medication withdrawal in older fallers: results from the Improving Medication Prescribing to reduce Risk Of FALLs (IMPROveFALL) trial. Age Ageing. 2016;46(1):142–6.

Hilmer SN, Gnjidic D, Le Couteur DG. Thinking through the medication list - appropriate prescribing and deprescribing in robust and frail older patients. Aust Fam Physician. 2012;41(12):924–8.

Tannenbaum C, Martin P, Tamblyn R, et al. Reduction of inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions among older adults through direct patient education: the EMPOWER cluster randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(6):890–8.

Campbell AJ, Robertson MC, Gardner MM, et al. Psychotropic medication withdrawal and a home-based exercise program to prevent falls: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47(7):850–3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study received financial and logistic support from the Réseau québécois de recherche sur le vieillissement du Fonds de recherche québecois—santé (MJS and study team) and the Quebec Centre for Excellence in Aging of the Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux de la Capitale-Nationale (CIUSSSCN) (EK, MJS and study team) and from the Centre de recherche du CHU de Québec. None of the financial contributors participated in collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Edeltraut Kröger, Marilyn Simard, Marie-Josée Sirois, Marianne Giroux, Caroline Sirois, Lisa Kouladjian-O’Donnell, Emily Reeve, Sarah Hilmer, Pierre-Hugues Carmichael and Marcel Émond declare that they have no conflict of interest relevant to the content of this publication.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kröger, E., Simard, M., Sirois, MJ. et al. Is the Drug Burden Index Related to Declining Functional Status at Follow-up in Community-Dwelling Seniors Consulting for Minor Injuries? Results from the Canadian Emergency Team Initiative Cohort Study. Drugs Aging 36, 73–83 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-018-0604-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-018-0604-9