Abstract

Introduction

Active surveillance pharmacovigilance is a systematic approach to medicine safety assessment and health systems strengthening, but has not been widely implemented in low- and middle-income countries. This study aimed to assess the cost effectiveness of a national active surveillance pharmacovigilance system for highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) compared with the existing spontaneous reporting system in Namibia.

Methods

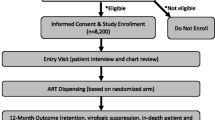

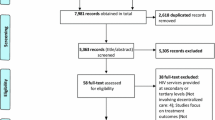

A cost–utility analysis from a governmental perspective compared active surveillance pharmacovigilance to spontaneous reporting. Data from a sentinel site active surveillance program in Namibia from August 2012 to April 2013 was projected to all HIV-infected adults initiating HAART in Namibia. Costs (pharmacovigilance program, HAART, adverse event [AE] treatment), quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), and incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs, dollars/QALY) were evaluated. Analysis was completed for (i) cohort analysis: a single cohort beginning HAART in 1 year in Namibia followed over their remaining lifetime, and (ii) population analysis: patients continued to enter and leave care and treatment over 10 years.

Results

For the cohort analysis, totals were US$21,267,902 (2015 US dollars) and 116,224 QALYs for care and treatment under active surveillance pharmacovigilance versus US$15,257,381 and 116,122 QALYs for care and treatment under spontaneous reporting pharmacovigilance, resulting in an ICER of US$58,867/QALY for active surveillance compared with spontaneous reporting pharmacovigilance. The population analysis ICER was US$4989/QALY. Results were sensitive to quality of life associated with AEs.

Conclusion

Active surveillance pharmacovigilance was projected to be highly cost effective to improve treatment for HIV in Namibia. Active surveillance pharmacovigilance may be valuable to improve lives of HIV patients and more efficiently allocate health resources in Namibia.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization WHO. The Importance of Pharmacovigilance—Safety Monitoring of medicinal products. 2002 [Internet]. Essential Medicines and Health Products Information Portal A World Health Organization resource; 2002;3–44. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js4893e/.

Al-Dakkak I, Patel S, McCann E, Gadkari A, Prajapati G, Maiese EM. The impact of specific HIV treatment-related adverse events on adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Care [Internet]. 2013;25(4):400–14. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22908886.

Bakare N, Edwards IR, Stergachis A, Pal S, Holmes CB, Lindquist M, et al. Global pharmacovigilance for antiretroviral drugs: overcoming contrasting priorities. PLoS Med [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2013 Oct 28];8(7):e1001054. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18070223.

Patel H, Parthasarathi G, Ramesh M. Pharmacovigilance of anti-neoplastic agents in a developing country—a report through a spontaneous reporting & continuous monitoring system. Value Health [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2016 Jan 5];18(7):A429–30. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26532417.

Ruud KW, Srinivas SC, Toverud E-L. Addressing gaps in pharmacovigilance practices in the antiretroviral therapy program in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Res Social Adm Pharm [Internet]. 2010;6(4):345–53. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21111391.

Centres P. A Practical Handbook on the Pharmacovigilance of Antiretroviral medicines. 2009 [cited 2013 Oct 28];150. Available from: http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=GlTtJsXfb9QC&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=hiv+pharmacovigilance&ots=PqWSKdKWT_&sig=1LEZbWu8qyePV045FOyLCW69LwE#v=onepage&q&f=true.

Holtz L, Cecilio L, Minowa E, Julian G. Pharmacovigilance in Oncology: Knowledge and Perception on Adverse Events Reporting in Brazil. Value Health [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2016 Jan 5];18(7):A815. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26534347.

Management Sciences for Health. Strengthening Pharmaceutical Systems [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2014 Mar 11]. Available from: https://depts.washington.edu/deptgh/globalmed/projects/strengthening-pharmaceutical-systems-sps/.

World Health Organisation. World Health Organization. Pharmacovigilance for antiretrovirals in resource-poor countries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007.

Nsubuga P, White ME, Thacker SB, Anderson MA, Blount SB, Broome CV, et al. Public health surveillance: a tool for targeting and monitoring interventions. Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, et al., editors. Dis control priorities dev ctries [Internet]. 2nd ed. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2006 [cited 2014 Jan 21];2:997–1018. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11770/.

Kouadio KI, Clement P, Bolongei J, Tamba A, Gasasira AN, Warsame A, et al. Epidemiological and surveillance response to Ebola virus disease outbreak in Lofa county, Liberia (March–September, 2014); lessons learned. PLoS Curr [Internet]. 2015 Jan [cited 2016 Mar 14];7. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4447624&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Pal SN, Duncombe C, Falzon D, Olsson S. WHO strategy for collecting safety data in public health programmes: Complementing spontaneous reporting systems. Drug Saf. 2013;36(2):75–81.

Miller V, Nwokike J, Stergachis A. Pharmacovigilance and global HIV/AIDS. Curr Opin HIV AIDS [Internet]. 2012;7(4):299–304. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22627711.

Eichler H-G, Bloechl-Daum B, Brasseur D, Breckenridge A, Leufkens H, Raine J, et al. The risks of risk aversion in drug regulation. Nat Rev Drug Discov [Internet]. 2013;12(12):907–16. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24232377.

Bouvy JC, Ebbers HC, Schellekens H, Koopmanschap MA. The cost-effectiveness of periodic safety update reports for biologicals in Europe. Clin Pharmacol Ther [Internet]. 2013;93(5):433–42. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23549148.

Bouvy JC, Koopmanschap MA, Shah RR, Schellekens H. The cost-effectiveness of drug regulation: the example of thorough QT/QTc studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther [Internet]. 2012;91(2):281–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22205197.

Bouvy JC, Koopmanschap MA, Schellekens H. Value for money of drug regulation. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res [Internet]. 2012;12(3):247–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22812545.

Bouvy J, Weemers J, Schellekens H, Koopmanschap M. Willingness to pay for adverse drug event regulatory actions. Pharmacoeconomics [Internet]. 2011;29(11):963–75. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21910513.

Babigumira JB, Stergachis A, Choi HL, Dodoo A, Nwokike J, Garrison LP. A framework for assessing the economic value of pharmacovigilance in low- and middle-income countries. Drug Saf [Internet]. 2014;37(3):127–34. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24550105.

Namibia | SIAPS Program [Internet]. [cited 2015 Nov 30]. Available from: http://siapsprogram.org/wherewework/namibia/.

Mann M, Mengistu A, Gaeseb J, Sagwa E, Mazibuko G, Baeten JM, Babigumira JB, Garrison LP, Stergachis A. Sentinel site active surveillance of safety of first-line antiretroviral medicines in Namibia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016. doi:10.1002/pds.4022.

Gold MR, Siegel JE, Russell LB, Weinstein MC. Cost-effectiveness in health and medicine [Internet]. J Ment Health Policy Econ. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. p. 425. Available from: http://books.google.com/books?id=HWttErwnBHsC&pgis=1.

Mengistu A, Gaeseb J, Stergachis A, Mann M, Sagwa E, Mazibuko G. Technical Report of the Active Surveillance of Safety of First line Antiretroviral Medicines in Windhoek Central & Katutura Intermediate Hospital. [Internet]. Submitted to the US Agency for International Development by the Systems for Improved Access to Pharmaceuticals; 2014. Available from: http://siapsprogram.org/publication/sentinel-site-active-surveillance-of-the-safety-of-first-line-antiretroviral-medicines-in-windhoek-central-hospital-and-katutura-intermediate-hospital/.

IHME Viz Hub. Mortality Viz [Internet]. [cited 2016 Apr 11]. Available from: http://vizhub.healthdata.org/mortality/.

Louwagie GM, Bachmann MO, Meyer K, Booysen F le R, Fairall LR, Heunis C. Highly active antiretroviral treatment and health related quality of life in South African adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a cross-sectional analytical study. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2007;7:244–5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17854510.

Pitt J, Myer L, Wood R. Quality of life and the impact of drug toxicities in a South African community-based antiretroviral programme. J Int AIDS Soc [Internet]. 2009;12:5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19393051.

Robberstad B, Olsen JA. The health related quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa— a literature review and focus group study. Cost Eff Resour Alloc [Internet]. 2010;8:5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20398367.

Wouters E, Heunis C, van Rensburg D, Meulemans H. Physical and emotional health outcomes after 12 months of public-sector antiretroviral treatment in the Free State Province of South Africa: a longitudinal study using structural equation modelling. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2009;9:103–11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19368714.

Bendavid E, Grant P, Talbot A, Owens DK, Zolopa A. Cost-effectiveness of antiretroviral regimens in the World Health Organization’s treatment guidelines: a South African analysis. AIDS [Internet]. 2011;25(July 2010):211–20. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21124202.

World Bank. Namibia | Data [Internet]. [cited 2015 May 16]. Available from: http://data.worldbank.org/country/namibia.

UNAIDS. Namibia [Internet]. [cited 2013 Oct 28]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/namibia/.

Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS)–Explanation and elaboration: a report of the ISPOR Health Economic Evaluations Publication Guidelines Task Force. Value Heal. 2013;16:231–50.

Republic of Namibia Ministry of Health and Social Services. The Namibia AIDS Response Progress Report 2015 [Internet]. [cited 2016 Apr 8]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/NAM_narrative_report_2015.pdf.

Republic of Namibia Ministry of Health and Social Services. GLOBAL AIDS RESPONSE PROGRESS REPORTING 2013 Monitoring the 2011 Political Declaration on HIV/AIDS [Internet]. Directorate of Special Programmes Division Expanded National HIV/AIDS Coordination Subdivision: Response Monitoring and Evaluation. [cited 2015 Dec 8]. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/NAM_narrative_report_2014.pdf.

WHO. WHO CHOICE: cost effectiveness thresholds [Internet]. [cited 2015 May 28]. Available from: http://www.who.int/choice/costs/CER_thresholds/en/.

Services M of H and S. Namibia Standard Treatment Guidelines. First Edition, 2011 [Internet]. 2011. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s19260en/s19260en.pdf.

UNAIDS. 90-90-90 An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. 2014;40. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2014/90-90-90.

Masenyetse LJ, Manda SO, Mwambi HG. An assessment of adverse drug reactions among HIV positive patients receiving antiretroviral treatment in South Africa. AIDS Res Ther [Internet]. 2015;12:6. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25745501.

Rosen S, Long L, Fox M, Sanne I. Cost and cost-effectiveness of switching from stavudine to tenofovir in first-line antiretroviral regimens in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr [Internet]. 2008;48(3):334–44. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18545151.

Anwikar SR, Bandekar MS, Smrati B, Pazare AP, Tatke PA, Kshirsagar NA. HAART induced adverse drug reactions: A retrospective analysis at a tertiary referral health care center in India. Int J Risk Saf Med [Internet]. 2011;23(3):163–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22020396.

Marshall C, Richards M, McBryde E. Do active surveillance and contact precautions reduce MRSA acquisition? A prospective interrupted time series. PLoS One [Internet]. Public Library of Science; 2013 [cited 2016 Apr 11];8(3):e58112. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0058112.

Republic of Namibia Ministry of Health and Social Services. Namibia Standard Treatment Guidelines [Internet]. 2011. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s19260en/s19260en.pdf.

Fox MP, Rosen S. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs up to three years on treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, 2007-2009: systematic review. Trop Med Int Health [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2016 Apr 1];15 Suppl 1:1–15. Available from: http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2948795&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract.

Disease-specific Toolkits. Pharmacovigilance Toolkit. [cited 2014 Feb 23];(January 2012):1–117. Available from: http://www.pvtoolkit.org.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This report was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the US Agency for International Development (USAID), under the terms of cooperative Agreement Number AID-OAA-A-11-00021. The contents are the responsibility of Management Sciences for Health and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

Conflict of interest

Marita Mann, Assegid Mengistu, Johannes Gaeseb, Evans Sagwa, Greatjoy Mazibuko, Joseph B. Babigumira, Louis P. Garrison, Jr., and Andy Stergachis have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mann, M., Mengistu, A., Gaeseb, J. et al. Active Surveillance versus Spontaneous Reporting for First-Line Antiretroviral Medicines in Namibia: A Cost–Utility Analysis. Drug Saf 39, 859–872 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-016-0432-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-016-0432-y