Abstract

Background

A histamine-2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) is one of the common gastroprotective co-therapies used with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for the prevention or treatment of peptic ulcers (PUs). To date, no study has directly compared the prophylactic effectiveness between high-dose and low-dose H2RA.

Objective

Our objective was to compare the effectiveness of high-dose versus low-dose H2RAs in the primary prophylaxis of PUs among short-term NSAID users.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (CDARS) in Hong Kong. Patients aged 18 years or above who received a single prescription of oral NSAID with oral H2RA were identified within the study period (1 January 2009–31 December 2012). Patients with a history of or risk factors for PU in the corresponding 2 years prior to the index date (of the first NSAID prescription) were excluded. Log binomial regression analysis was used to calculate the relative risk of PU among NSAID users with high-dose H2RA versus low-dose H2RA exposure.

Results

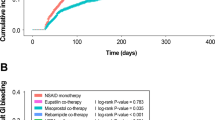

Among the NSAID cohort (n = 102,042), 77,509 (76 %) were on low-dose H2RA and 24,533 (24 %) were on high-dose H2RA. Of the total 69 PU cases identified during the drug exposure period, 64 (0.08 %) received low-dose-H2RA and five (0.02 %) received high-dose H2RA. The overall absolute risk of PUs for NSAID users whilst on H2RA was approximately 1 per 1,479 patients. The adjusted relative risk for NSAID users receiving high-dose H2RA versus low-dose H2RA was 0.32 (95 % confidence interval [CI] 0.13–0.79). Patients aged ≥65 years, receiving a longer duration of treatment, or with concomitant use of antiplatelet agents were found to be at higher risk of PU.

Conclusion

High-dose H2RA showed greater effectiveness than low-dose H2RA in the primary prophylaxis of NSAID-associated PUs in short-term new users.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lee YC. Effect and treatment of chronic pain in inflammatory arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2013;15(1):300.

Kingsbury SR, Hensor EM, Walsh CA, Hochberg MC, Conaghan PG. How do people with knee osteoarthritis use osteoarthritis pain medications and does this change over time? Data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(5):R106.

Rott KT, Agudelo CA. Gout. JAMA. 2003;289(21):2857–60.

Grosser T, Smyth E, FitzGerald GA. Anti-inflammatory, antipyretic, and analgesic agents; pharmacotherapy of gout. In: Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC, editors. Goodman & Gilman’s. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2011.

Patrignani P, Tacconelli S, Bruno A, Sostres C, Lanas A. Managing the adverse effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2011;4(5):605–21.

MacDonald TM, Morant SV, Robinson GC, Shield MJ, McGilchrist MM, Murray FE, et al. Association of upper gastrointestinal toxicity of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with continued exposure: cohort study. BMJ. 1997;315(7119):1333–7.

Lanza FL. A guideline for the treatment and prevention of NSAID-induced ulcers. Members of the Ad Hoc Committee on Practice Parameters of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(11):2037–46.

Rostom A, Muir K, Dube C, Lanas A, Jolicoeur E, Tugwell P. Prevention of NSAID-related upper gastrointestinal toxicity: a meta-analysis of traditional NSAIDs with gastroprotection and COX-2 inhibitors. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2009;1(1):47–71.

Hooper L, Brown TJ, Elliott RA, Payne K, Roberts C, Symmons D. The effectiveness of five strategies for the prevention of gastrointestinal toxicity induced by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: systematic review. BMJ. 2004;329(7472):948–52.

Lancaster-Smith MJ, Jaderberg ME, Jackson DA. Ranitidine in the treatment of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug associated gastric and duodenal ulcers. Gut. 1991;32(3):252–5.

Elliott RA, Hooper L, Payne K, Brown TJ, Roberts C, Symmons D. Preventing non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastrointestinal toxicity: are older strategies more cost-effective in the general population? Rheumatology. 2006;45(5):606–13.

Lazzaroni M, Porro GB. Management of NSAID-induced gastrointestinal toxicity focus on proton pump inhibitors. Drugs. 2009;69(1):51–69.

Moore A, Bjarnason I, Cryer B, Garcia-Rodriguez L, Goldkind L, Lanas A, et al. Evidence for endoscopic ulcers as meaningful surrogate endpoint for clinically significant upper gastrointestinal harm. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(11):1156–63.

Wolde ST, Dijkmans BA, Janssen M, Hermans J, Lamers CB. High-dose ranitidine for the prevention of recurrent peptic ulcer disease in rheumatoid arthritis patients taking NSAIDs. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10(3):347–51.

Hudson N, Taha AS, Russell RI, Trye P, Cottrell J, Mann SG, et al. Famotidine for healing and maintenance in nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-associated gastroduodenal ulceration. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(6):1817–22.

Graham DY. Endoscopic ulcers are neither meaningful nor validated as a surrogate for clinically significant upper gastrointestinal harm. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(11):1147–50.

Rostom A, Dube C, Wells GA, Tugwell P, Welch V, Jolicoeur E, McGowan J, Lanas A. Prevention of NSAID-induced gastroduodenal ulcers (Review). The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011(6):1–176.

Yeomans ND, Tulassay Z, Juhasz L, Racz I, Howard JM, van Rensburg CJ, et al. A comparison of omeprazole with ranitidine for ulcers associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Acid suppression trial: ranitidine versus omeprazole for NSAID-associated Ulcer Treatment (ASTRONAUT) Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(11):719–26.

Ho CW, Tse YK, Wu B, Mulder CJ, Chan FK. The use of prophylactic gastroprotective therapy in patients with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug- and aspirin-associated ulcer bleeding: a cross-sectional study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37(8):819–24.

Hospital Authority. Introduction (Accessed on: 15 November 2013). Available from: http://www.ha.org.hk/visitor/ha_visitor_index.asp?Content_ID=10008&Lang=ENG&Dimension=100&Parent_ID=10004.

Information Services Department HKSARG. Hong Kong: The facts 2013 (Accessed on:15 November 2013). Available from: http://www.gov.hk/en/about/abouthk/factsheets/docs/population.pdf.

Hospital Authority. Clusters, Hospitals & Institutions (Accessed on:15 November 2013). Available from: http://www.ha.org.hk/visitor/ha_visitor_index.asp?Content_ID=10036&Lang=ENG&Dimension=100&Parent_ID=10004.

Wong MC, Tam WW, Cheung CS, Tong EL, Sek AC, John G, et al. Initial antihypertensive prescription and switching: a 5 year cohort study from 250,851 patients. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53625.

Mok CC, Kwok CL, Ho LY, Chan PT, Yip SF. Life expectancy, standardized mortality ratios, and causes of death in six rheumatic diseases in Hong Kong. China. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(5):1182–9.

Cheuk BL, Cheung GC, Cheng SW. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in a Chinese population. Br J Surg. 2004;91(4):424–8.

Chui CS, Man KK, Cheng CL, Chan EW, Lau WC, Cheng VC et al. An investigation of the potential association between retinal detachment and oral fluoroquinolones: a self-controlled case series study. J Antimicrob Chemother. Epub ahead of print 2014 May 15.

Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary (BNF). 63rd ed. London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutial Press; 2012.

Lanza FL, Chan FK, Quigley EM. Guidelines for prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(3):728–38.

Gutthann SP, Garcia Rodriguez LA, Raiford DS. Individual nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and other risk factors for upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation. Epidemiology. 1997;8(1):18–24.

Langman MJ, Weil J, Wainwright P, Lawson DH, Rawlins MD, Logan RF, et al. Risks of bleeding peptic ulcer associated with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Lancet. 1994;343(8905):1075–8.

Wilson EB. Probable inference, the law of succession, and statistical inference. J Am Statist Assoc. 1927;22(158):209–12.

Rothman KJ, Greendland S. Modern Epidemiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998.

Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ. 1995;310(6977):452–4.

Kelsey JL, Whittemore AS, Evans AS, Thompson WD. Methods in Observational Epidemiology. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996.

Tuskey A, Peura D. The use of H2 antagonists in treating and preventing NSAID-induced mucosal damage. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15(Suppl 3):S6.

Mejia A, Kraft WK. Acid peptic diseases: pharmacological approach to treatment. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2009;2(3):295–314.

Chan FK, Sung JJ. Role of acid suppressants in prophylaxis of NSAID damage. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;15(3):433–45.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NSAIDs: prescribing issues summary 2013 (Accessed on: 3 Nov 2013). Available from: http://cks.nice.org.uk/nsaids-prescribing-issues#!scenariorecommendation:3.

Rostom A, Moayyedi P, Hunt R. Canadian consensus guidelines on long-term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy and the need for gastroprotection: benefits versus risks. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(5):481–96.

Brown TJ, Hooper L, Elliott RA, Payne K, Webb R, Roberts C, et al. A comparison of the cost-effectiveness of five strategies for the prevention of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced gastrointestinal toxicity: a systematic review with economic modelling. Health Technol Assess. 2006;10(38):1–183.

Barozzi N, Tett SE. Gastroprotective drugs in Australia: utilization patterns between 1997 and 2006 in relation to NSAID prescribing. Clin Ther. 2009;31(4):849–61.

Valkhoff VE, van Soest EM, Sturkenboom MC, Kuipers EJ. Time-trends in gastroprotection with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(11):1218–28.

Lopez-Pintor E, Lumbreras B. Use of gastrointestinal prophylaxis in NSAID patients: a cross sectional study in community pharmacies. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(2):155–64.

Laine L. Approaches to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in the high-risk patient. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(3):594–606.

Kang JM, Kim N, Lee BH, Park HK, Jo HJ, Shin CM, et al. Risk factors for peptic ulcer bleeding in terms of Helicobacter pylori, NSAIDs, and antiplatelet agents. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(11):1295–301.

Laine L, Curtis SP, Cryer B, Kaur A, Cannon CP. Risk factors for NSAID-associated upper GI clinical events in a long-term prospective study of 34,701 arthritis patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32(10):1240–8.

Laine L. GI risk and risk factors of NSAIDs. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2006;47(Suppl 1):S60–6.

Ray WA. Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: new-user designs. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(9):915–20.

Masclee GM, Valkhoff VE, van Soest EM, Schade R, Mazzaglia G, Molokhia M, et al. Cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors or nonselective NSAIDs plus gastroprotective agents: what to prescribe in daily clinical practice? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38(2):178–89.

WHO and Hong Kong Department of Health. Hong Kong (China) Health Service Delivery Profile 2012 (Accessed on:15 Novermber 2013). Available from: http://www.wpro.who.int/health_services/service_delivery_profile_hong_kong_%28china%29.pdf.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Vincent C.C. Cheng for his support on the verification of ICD-9-CM codes for related diagnosis/procedures in this study. We also thank Lisa Wong for proofreading and editing the manuscript.

Declaration of funding interests

None to declare.

Declaration of competing interest

Ying He, Esther W. Chan, Kenneth K.C. Man, Wallis C.Y. Lau, Wai K. Leung, Lai M. Ho, and Ian C.K. Wong declare no support from any organization for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organization that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/HA Hong Kong West Cluster (IRB reference number: UW 12-196).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

He, Y., Chan, E.W., Man, K.K.C. et al. Dosage Effects of Histamine-2 Receptor Antagonist on the Primary Prophylaxis of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug (NSAID)-Associated Peptic Ulcers: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Drug Saf 37, 711–721 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-014-0209-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-014-0209-0