Abstract

Background

Significant knowledge gaps exist related to evaluating health product risk communication effectiveness in a regulatory setting. To this end, Health Canada is assessing methods to evaluate the effectiveness of their health product risk communications in an attempt to identify best practices.

Objective

We examined the health literacy burden of Public Advisories (PAs) before and after implementation of a new template. We also compared two methods for their usefulness and applicability in a regulatory setting.

Methods

Suitability assessment of materials (SAM) and readability tests were run by three independent evaluators on 46 PAs (14 “Pre-format change” and 32 “Post-format change”). These tests provided adequacy scores for various health literacy elements and corresponding scholastic grades.

Results

PAs using the new template scored better, with an average increase of 18 percentage points (p < 0.001), on the SAM test. All of the 46 PAs evaluated were rated as “requiring a college/university education comprehension level” using readability tests. Results among readability tests were comparable.

Conclusion

Improvements made to Health Canada’s PA template had a measurable, positive effect on reducing the health literacy burden, based on the SAM results. A greater focus on the use of plain language would likely add to this effect. The SAM test emerged as a robust, reliable, and informative health literacy tool to assess risk messages and identify further improvement efforts. Regulators, industry, and public sector organizations involved in communicating health product risk information should consider the use of this test as a best practice to evaluate health literacy burden.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Background

Health Canada is the federal department responsible for maintaining and improving the health of Canadians [1]. Its mission is to make Canada one of the healthiest countries in the world through evidence-based decision making, public consultations, risk communications, and by encouraging Canadians to take an active role in their personal health [1]. Part of Health Canada’s responsibility is to identify, assess, and communicate safety information to Canadians using a variety of risk communication tools. Specific tools are selected according to the content, urgency, target audience, and developer of the risk communication [2]. These tools include Dear Healthcare Professional Letters, Notices to Hospitals, the Canadian Adverse Reaction Newsletter, Fact Sheets, Product Monographs, Recall Notices, Public Communications, Information Updates, It’s Your Health Publications, Foreign Product Alerts, and Public Advisories (PAs). PAs are a particularly important risk communication tool used for urgent and high-risk issues [2]. The importance of PAs are highlighted in their definition: “to inform the public of possible serious health hazards and enable Canadians to make informed decisions concerning the continued use of marketed health products” [2].

A PA template revision occurred in 2010 with a goal of improving the quality and accessibility of risk communications for the public. The revisions aligned Health Canada’s PAs with international regulators and attempted to clarify information through several mechanisms. The new template clearly identified health risks, actions to address the identified risks, and ways that Canadians could protect themselves (see Electronic Supplementary Material I for original and revised PA examples). These changes were recommended through different external drivers (e.g., The Office of the Auditor General of Canada and the Carlin Jury recommendations) and endorsed by Health Canada’s Expert Advisory Committee on the Vigilance of Health Products [3, 4]. The revised template shifted from a media-based “press release” format to a patient-directed “question–answer” style format and included the use of prioritized message order, boxed text, visual cues, and key bullets. Although not included in the template revisions themselves, an emphasis on easy-to-read titles and a reading grade level of 6–8 was targeted for all public communications, as per recommendations made in Health Canada’s Clear Writing Guide. Taken together, these revisions attempted to improve the way Health Canada communicated risk information to the general public.

Communicating health risk information is a key part of risk management and public health education [5, 6]. Health Canada’s risk communications are written with the assumption that readers are able to understand and make use of the information being provided, which is typically determined by the health literacy level of the reader. Health literacy is a person’s “ability to access, understand, evaluate and communicate information to promote, maintain and improve health in various life-course settings” [7]. Skills that contribute to health literacy include reading, writing, listening, speaking, numeracy, critical analysis, and communication and interaction skills [8]. Health literacy extends beyond general literacy, as it requires the reader to understand concepts related to science and medicine [8]. This poses a challenge in providing useful, evidence-based risk information while engaging Canadians through text they can understand.

The field of health literacy has experienced significant innovation throughout the past 25 years and continues to be a topic of interest as an important contributor to overall health [9, 10]. Low health literacy individuals mismanage chronic illness, use preventative services less, and have poorer health in general [11, 12]. Studies have shown that the link between health literacy and population health may have direct implications on healthcare spending and patient decision making [13]. Yet nearly 60 % of Canadians 16 years and older do not have the minimum health literacy levels needed to fully understand the health information they receive [13]. This is further pronounced in Canadian seniors, with more than 80 % having poor health literacy levels [13, 14]. Previous internal work found that PAs were written at a graduate student’s level—well above the average health literacy level of the general public.

Although we provide a general definition of health literacy, defining and measuring health literacy has not yet achieved consensus in the literature [15]. Furthermore, health literacy is often inferred from tests that measure the ‘health literacy burden’ of materials (i.e., how difficult materials would be for an individual with a particular health literacy level) as opposed to direct means, such as focus groups [16, 17]. This has led to a variety of tools being used to measure the health literacy burden, many of which vary in validity and applicability [18–20].

For this study, two types of health literacy tools were used to compare PAs: readability formulas and suitability assessment of materials (SAM) tests. These two tools were selected for three key reasons. First, readability and SAM tests were found to be very common in the literature as a means to evaluate the clarity or health literacy burden of printed and/or computer-viewed materials [21–23]. Second, the tools were inexpensive, easy to use, and not resource intensive; an important consideration during times of limited government spending [24]. Finally, they provided a systematic, reliable way to evaluate health literacy concepts in written and visual materials [24, 25].

Although readability and SAM tests overlap in what they measure, the two tools differ in what data they can provide. Readability tests use mathematical formulas to measure word length, number of syllables per word, number of words per sentence, and number of sentences per paragraph [26]. They provide an objective score that loosely translates into what school grade equivalent would be needed for an individual to read and understand the text [26]. For example, a text that scored 6.0 would generally be appropriate for a grade 6 student in elementary school.

Readability software was compared with a test that takes additional health literacy factors into consideration. The SAM test considers content, literacy demand, graphics, layout, font style, stimulatory factors, and motivational cues when evaluating texts [27]. The SAM test is subjective but has undergone extensive validation across various cultures to support it as a reflection of how low health literacy individuals would judge materials [27]. Members of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, University of North Carolina School of Public Health and Veterans Affairs Hospital contributed to determining if the SAM scores can measure how clear written text is for a low health literacy patient [27]. Although not validated by Health Canada, studies on risk communication tools support the validity of SAM tests in this context [28, 29].

The goal of this study was to compare PAs written using the original (Pre-format) and the revised (Post-format) template through readability and SAM tests. Additionally, the tests themselves were evaluated for their usefulness and applicability in a regulatory setting.

2 Materials and Methods

This retrospective study collected PAs from Health Canada’s website (http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/medeff/advisories-avis/index-eng.php). Only PAs written for marketed health products posted between 3 May 2009 and 4 May 2011 were considered for this study. A “health product” was defined as a pharmaceutical, biologic, natural health product, or medical device. 92 PAs were originally collected. This study excluded any non-English PAs; therefore, 46 PAs were included for analysis (14 “Pre-format change” and 32 “Post-format change”).

2.1 Readability Tests

Assessment of readability was performed using Readability Studio 2009, version 3.2.7.0 (Oleander Software, Vandalia, OH, USA). PA text was entered into the software by the evaluators. Non-body text, such as the advisory number, date, and the “for immediate release” disclaimer were not included. For “Post-format change” samples, the “Related Health Canada Web Content” section was also omitted since it is not directly part of the risk communication. All graphics, tables, corresponding titles, and captions were excluded from the readability tests. Bullet points were converted automatically by the software into sentences.

Seven different readability tests were performed on each PA and then compared with each other to determine school grade equivalents. An average of all seven readability tests was also obtained for each PA. These tests show the education level that would be required to understand the text, with results expressed in a school grade equivalent. Table 1 provides a list of the tests used, the applicable scoring ranges, and how these scores translate into school grade equivalents.

2.2 Suitability Assessment of Materials (SAM) Tests

Suitability assessment of materials testing was independently performed on each PA by three different evaluators. PAs were printed and assessed in this format. The method required evaluators scoring document elements as either 0 (“inadequate”), 1 (“adequate”) or 2 (“superior”) based on elements within five categories (Table 2). Overall SAM scores were summed and divided by the total possible SAM score to create a percentage. Percentages were interpreted as follows: 70–100 % was for superior material that was suitable for low health literacy individuals, 40–69 % was for adequate material that may or may not be understood by low health literacy individuals, and 0–39 % was for not suitable material that would not be understood by low health literacy individuals. For more details on how to score materials, the elucidation of each category/elements and construct validation of the SAM, refer to Doak et al. [27].

Since the SAM was originally designed for patient education print materials, not all categories applied to the assessment of the PA. As a result, a modified SAM test was performed on all PAs in the study with the removal of certain categories/elements based on irrelevance or lack of applicability. Summary reviews, cover graphics, and lists/tables were not included because PAs do not typically have those items. “Interaction Used” was removed because PAs are not a health product risk communication designed to work through an interactive process. Lastly, “Cultural Appropriateness” was removed because it was outside the scope of this study.

2.3 Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). The Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparisons between “Pre-format change” and “Post-format change” PAs to measure the significance of differences seen in the results. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. All values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean.

3 Results

3.1 Readability Tests

The results in Fig. 1 show the average readability score, in grade levels, of PAs developed with either the original (“Pre-format change”) or revised (“Post-format change”) template. The majority of PAs fell into the grade 13–15 range regardless of the template used. Furthermore, there was little to no difference observed between readability tests (see Electronic Supplementary Material II for readability and SAM scores).

3.2 SAM Tests

The results in Fig. 2 show the average SAM score for PAs using the original or revised template. On average, PAs written using the original template scored adequately, at 51 %. PAs written using the revised template also scored adequately, at 69 %. The SAM scores increased, on average, by 18 percentage points and were statistically significant (p < 0.001). Grouping of PAs was attempted for similar products and classes of drugs, but no differences in scoring trends were observed.

Individual categories in the SAM test were analyzed and, as seen in Fig. 3, significantly improved when the revised template was used. “Literacy Demand,” “Graphics,” and “Layout and Typography” were increased by 25.7 (p < 0.001), 19.7 (p = 0.020), and 27.8 (p < 0.001) percentage points, respectively.

Comparison of the average suitability assessment of materials results, by category, using Public Advisories “Pre-format change” (n = 14) versus “Post-format change” (n = 32). Values are mean ± standard error of the mean. C Content, G Graphics, L Literacy Demand, L&M Learning Stimulation and Motivation, L&T Layout and Typography, SAM suitability assessment of materials

An analysis of elements within the aforementioned categories indicated select improvements (Table 3). Two “Literacy Demand” factors, namely “Writing Style” (p < 0.001) and “Use of Learning Aids” (p < 0.001), improved significantly after the template was revised. In the “Graphics” category, “Captions” significantly improved (p < 0.001) from inadequate to adequate. “Layout” and “Subheadings” improved significantly (p < 0.001) in the “Layout and Typography” category, while “Typography” decreased significantly (p = 0.042). The use of subheadings improved from inadequate to superior. None of the elements under “Content” or “Learning Stimulation” changed significantly.

4 Discussion

This study compared PAs, before and after a template revision, using two different health literacy tools: readability and SAM tests. Readability tests are objective and provide a quantitative assessment of the text, limiting subjectivity. This tends to be crude, however, as it gives an idea of text difficulty without taking the entire document into context [25]. Text layout, organization of information, and pictures are completely ignored, even though they may be important in reducing the health literacy burden for the reader [25]. The SAM test, on the other hand, is subjective in nature and assesses text while considering many factors omitted in a readability test [27]. Although it can assess whether text is adequate for low health literacy individuals, it suffers more easily from subjectivity issues and biases [27]. The results of each test are discussed below.

4.1 Readability Tests

The average reading grade level for PAs did not change with the template revision. The readability test results for PAs remained at a grade 13–15 level (i.e., requiring a college or university education to understand) after implementation of the revised template. These results were consistent among all seven readability tests used and demonstrated that no obvious advantage exists in using one method over another in terms of sensitivity and specificity. Although these findings are not surprising, given the limited impact the template change had on content development, this result highlights the need for further attention to how content is written and developed for PAs.

Readability tests were inexpensive and not resource intense but limited, overall, when examined for their usefulness and applicability in a regulatory setting. The limitations were intrinsic; readability tests use mathematical formulas to account for factors such as the number of words per sentence, syllables per word, etc. [36]. As such, readability scores need to be scrutinized when used alone to avoid misinterpretation: shortening of words/sentences does not necessarily make things easier to understand; people do not process text the same way a computer does; and readability formulas do not capture other important parts of the health literacy burden [36]. As mentioned earlier, many factors impact the complexity of understanding scientific and medical literature; therefore, the use of readability tests as a standalone measure should be cautioned unless combined with more robust tests [36].

4.2 SAM Tests

SAM tests consider a number of relevant factors such as presentation, context, and the use of images to measure the difficulty of a given text [27]. Although only capable of providing an estimate of the health literacy burden, SAM tests consider a greater array of health literacy factors than readability tests. Prioritized message order, boxed text, visual cues, and other factors contributed to better SAM scores in the revised PAs. PAs using the original format typically scored poorly (below 60 %) in many of the SAM categories. The overall “Pre-format change” average was ranked “Adequate”, but near the low end of the scale, at 51 % (Fig. 2). PAs using the revised template showed a significant improvement, with the overall average increasing by 18 percentage points (p < 0.001) and shifting towards the high end of the adequacy scale, at 69 %. This was only 1 percentage point away from achieving an average score of “Superior,” indicating that most materials were near suitable for low health literacy individuals.

Improvements in “Literacy Demand” were due to the use of an active voice, adoption of a more conversational style of writing, and addition of learning aids. Greater use of active voice in “Post-format change” PAs was apparent throughout, particularly in the “What You Should Do” section. For example, “Pre-format change” PAs would recommend contacting a healthcare professional in the following manner: “Consumers who have purchased ‘product X’ are advised not to use the product and to consult with a medical professional if they have used the product and have concerns about their health.” “Post-format change” PAs, however, would state: “Consult your healthcare practitioner if you have used any of these products and are concerned about your health”. This section used imperative tone and started with action verbs, such as “Consult,” “Read,” and “Report.”

Other improvements included the use of “road-signs,” or headers, which added structure and allowed the reader to better sort the information. An improved sentence structure, through a more dedicated use of context, ensured that important health-related information was more visible than in previous PAs. Improvements in context were important, but must be considered in relation to other elements. DeWalt et al. [37] reported that risk communication providers sometimes believe that context dictates readability and usability of a document. In reality, context is only one component of a clear risk communication and cannot solely determine how well the information will be understood by the end user. For this reason, DeWalt et al. [37] created a toolkit that was designed to address health literacy-based barriers in a variety of ways without over-relying on context.

Another category that significantly improved was “Graphics.” “Graphics” scored poorly with “Pre-format change” PAs in two areas: “Relevance” and “Captions.” The “Relevance” was inadequate because PAs generally failed to illustrate key points visually or contained visual distractions. “Captions” were rarely included or failed to provide a quick reference to the reader about the graphic. Although this section improved significantly (p = 0.020), from not suitable to adequate, failure to reach a superior score provides evidence that PAs did not fully capitalize on the potential for using graphics effectively. The “Post-format change” PAs did, however, use pictures, tables/charts, and other visual aids more often. Most of the PAs using the revised template included a photograph of the particular health product along with a short caption (typically the name of the product). These photographs were meant to be simple and provide readers with a visual aid to facilitate product recognition. The use of images has been shown to improve attention to and recall of health material, thus playing a significant role in reducing the health literacy burden of information [38].

The “Layout and Typography” category experienced the greatest increase, as the revised template focused mainly on format elements such as font, layout, subheadings, and “chunking.” Font was standardized, illustrations were added in logical sequence, and colored boxes were used to highlight and divide important text and headers into easy-to-read sections. “Layout” and “Subheadings or ‘Chunking’” had significant increases in SAM scores after the template revision was implemented, making it the category that had the largest impact on improving SAM scores. Interestingly, “Typography” decreased significantly (although only marginally in score). This was most likely attributed to printer settings when PAs were produced for analysis, as evaluators noted that font sizes were smaller for several revised PAs even though the original source material was standardized for type size.

The “Content” category of the PAs remained unchanged with the template revision. This result was not surprising given that there was no change in the need for risk communications, the type of information that was communicated, or the scope of the PA’s objectives. As such, the SAM scores for “Purpose,” “Content Topics,” and “Scope” remained similar between “Pre-format change” and “Post-format change” PAs. The overall score in the “Content” category remained superior, but this does not preclude further improvements in future PAs. Including the purpose directly in the title, tailoring the scope of the information to the target audience and providing a short summary at the end of the information could improve SAM scores for the “Content” section.

Similarly, the SAM score for the “Learning Stimulation and Motivation” category remained unchanged after the template revisions. This result was also not surprising since the format change did not focus on adding desired behaviors or motivational points. Although this category scored in the superior range for both “Pre-format change” and “Post-format change” PAs, this was likely due to how information was presented and not because of interactive components. As other media (e.g., social media) become more prevalent in the risk communication process, this category may need to be studied further to determine how best to capitalize on elements related to “Learning Stimulation and Motivation.”

Overall, the SAM test emerged as a useful and applicable tool for evaluating health product risk communications in a regulatory setting. The tool was inexpensive and provided a more robust analysis of PAs before and after a template revision. The results also highlighted the impact the PA template had on SAM scores, providing targets for further improvement.

4.3 Limitations

There were several limitations to this study that the authors would like to acknowledge. The use of cultural analysis was omitted from the SAM test. Ensuring that risk communications issued by Health Canada were sensitive and motivating to such a broad range of ethnic groups was considered outside the scope and resources of this study. Further study, in this regard, would add another dimension to the findings in terms of how various cultural and linguistic backgrounds may absorb the information relayed by PAs.

A similar analysis of French PAs would undoubtedly provide a more generalizable study. Given the two official languages of Canada are French and English, future studies would provide more insight into the health literacy burden of French PAs.

As previously stated, the SAM test is subjective by nature, which can lead to significant bias in the end results. This subjectivity can negatively impact inter-rater reliability since evaluators may interpret elements differently. The use of more than one evaluator is recommended to reduce the potential for bias; however, all evaluators should discuss the relevance of test elements and how scoring will be conducted before testing begins. For example, deciding what text will be included, what counts as a table versus a list or picture, and how readability will be measured can help improve reliability among different evaluator results.

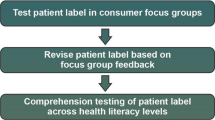

Finally, assessment of comprehension by means of public consultations was not performed as part of this study. Although conducting public consultations and focus groups would vastly improve understanding of the use and comprehensibility of PAs, these measures are resource intensive. The SAM was designed and validated with this in mind and attempts to gather consultation-like data in its assessment of health information. Furthermore, the SAM test measures the health literacy burden, which can be used to infer how clear the material will be for low health literacy individuals. That being said, the SAM results should be supported with consultations, if resources are available, to measure how clear a health product risk communication is to the target audience.

5 Conclusion

Implementation of a revised PA template reduced the health literacy burden of Health Canada’s PAs as measured by SAM tests; however, the revisions did not improve readability. The SAM test, as described in this study, is a useful, applicable tool in a regulatory setting. The findings are important to drug regulators who communicate risk information pertaining to health products, but should also be considered by industry and public sectors as a best practice for measuring the health literacy burden of risk communications.

Future research should focus on supporting data obtained from SAM tests with public consultations (such as focus groups) to more accurately validate this test as a measure of risk communication effectiveness. As well, studies should investigate if the SAM test is an informative tool for evaluating the effectiveness of French risk communications from the standpoint of clarity and readability.

References

Health Canada. About Health Canada (2012). http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/index-eng.php. Accessed 2 Nov 2012.

Health Canada. Description of current risk communication documents for marketed health products for human use – guidance document (2011). http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/pubs/medeff/_guide/2008-risk-risques_comm_guid-dir/index-eng.php. Accessed 15 Jul 2013.

Health Canada. Health Canada’s response to the Carlin Jury recommendations aimed at the department or directly relevant to its mandate (2011). http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/pubs/hpfb-dgpsa/inquest-enquete_carlin-eng.php. Accessed 1 Feb 2013.

Office of the Auditor General. 2011 June status report of the Auditor General. http://www.oag-bvg.gc.ca/internet/English/parl_oag_201106_06_e_35374.html. Accessed 11 Feb 2013.

Bahri P, Harrison-Woolrych M. Focusing on risk communication about medicines. Drug Saf. 2012;35(11):971–5.

Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int. 2000;15(3):259–67.

Neilsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA. What is health literacy? In: Committee on Health Literacy, editor. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. London: National Academies Press; 2004.

Coleman C, Kurtz-Rossi S, McKinney J, Pleasant A, Rootman I, Shohet L. The Calgary Charter on Health Literacy: rational and core principles for the development of health literacy curricula (2008). http://www.centreforliteracy.qc.ca/health_literacy/calgary_charter. Accessed 12 Feb 2013.

Hernandez L. Innovations in Health Literacy. In: Health Literacy: Improving Health, Health Systems and Health Policy Around the World. London: National Academies Press; 2013. http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=18325. Accessed 12 Jul 2013.

Pleasant A. Health literacy: an opportunity to improve individual, community and global health. New Dir Adult Contin Edu. 2011;130:43–53.

Murray S, Rudd R, Kirsch I, Yamamoto K, Grenier S. Health literacy in Canada: initial results from the International Literacy and Skills Survey 2007. Canadian Council of Learning. http://www.ccl-cca.ca/pdfs/HealthLiteracy/HealthLiteracyinCanada.pdf. Accessed 15 Jul 2013.

Baker D, Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson JA, Gazmararian JA, Huang J. Health literacy and mortality among elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(14):1503–9.

Rootman I, Gordon-El-Bihbety D. A vision for a health literate Canada: report of the Expert Panel on Health Literacy. Ottawa: Canadian Public Health Association; 2008. http://www.cpha.ca/en/portals/h-l/panel.aspx. Accessed 5 Jun 2013.

Statistics Canada. International Adult Literacy and Skills Survey (2005). http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SurvId=4406&SurvVer=1&InstaId=15966&InstaVer=2&SDDS=4406. Accessed 21 Mar 2013.

Pleasant A, McKinney J. Coming to consensus on health literacy measurement: an online discussion and consensus-gauging process. Nurs Outlook. 2011;59:95–106.

Weintraub D, Maliski S, Fink A, Choe S, Litwin MS. Suitability of prostate cancer education materials: applying a standardized assessment tool to currently available materials. Pat Edu Coun. 2004;55(2):275–80.

Hoffmann T, Mckenna K. Analysis of stroke patients’ and carers’ reading ability and the content and design of written materials: recommendations for improving written stroke information. Pat Edu Coun. 2006;60:286–93.

Rees C, Ford J, Sheard C. Patient information leaflets for prostate cancer: which leaflets should healthcare professionals recommend? Pat Edu Coun. 2003;49(3):263–72.

Winterhalter E. Assessing the health literacy environment: three domains of literacy evaluated in a pediatric diabetes clinic. Philadelphia: Thomas Jefferson University; 2012. http://jdc.jefferson.edu/mphcapstone_presentation/60/. Accessed 15 Jul 2013.

Wu AD, Begoray DL, Macdonald M, Wharf-Higgins J, Frankish J, Kwan B, et al. Developing and evaluating a relevant and feasible instrument for measuring health literacy of Canadian high school students. Health Promot Int. 2010;25(4):444–52.

Beyer DR, Lauer MS, Davis S. Readability of informed-consent forms. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(22):2262–3.

Kaphingst KA, Rudd R, DeJong W, Daltroy LH. Literacy demands of product information intended to supplement television direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertisements. Pat Edu Coun. 2004;55:293–300.

Helitzer D, Hollis C, Cotner J, Oestreicher N. Health literacy demands of written health information materials: an assessment of cervical cancer prevention materials. Cancer Control. 2009;16(1):70–8.

Smith S. SAM: suitability assessment of materials for evaluation of health-related information for adults (2012). http://aspiruslibrary.org/literacy/SAM.pdf. Accessed 15 Sep 2012.

Zarcadoolas C. The simplicity complex: exploring simplified health messages in a complex world. Health Promot Int. 2010;26:338–50.

Redish JC, Selzer J. The place of readability formulas in technical communications. Tech Commun. 1985;32(4):46–52.

Doak C, Doak LG, Root JH. Assessing Suitability of Materials. In: Belcher M, editor. Teaching patients with low literacy skills. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company; 1996.

Shieh C, Hosei B. Printed information materials: evaluation of readability and suitability. J Community Health Nurs. 2008;25(2):73–90.

Befort CA, Thomas JL, Daley CM, Rhode PC, Ahluwalia JS. Perceptions and beliefs about body size, weight, and weight loss among obese African American women: a qualitative inquiry. Health Educ Behav. 2008;35(3):410–26.

Smith EA, Senter RJ. Automated readability index. AMRL TR. 1967:1-14.

Coleman M, Liau T. A computer readability formula designed for machine scoring. J Appl Psychol. 1975;60:283–4.

Flesch R. A new readability yardstick. J Appl Psychol. 1948;32:221–33.

McLaughlin H. SMOG grading—a new readability formula. J Read. 1969;12(8):639–46.

Gunning R. The technique of clear writing. Michigan: McGraw-Hill; 1968.

Fry E. A readability formula that saves time. J Read. 1968;11:513–6.

Benjamin R. Reconstructing readability: recent developments and recommendations in the analysis of text difficulty. Educ Psychol Rev. 2011;24(1):63–88.

DeWalt AD, Broucksou KA, Hawk V, Brach C, Rudd R, Callahan L. Developing and testing the health literacy universal precautions toolkit. Nurs Outlook. 2011;59(2):85–94.

Houts PS, Doak C, Doak LG, Loscalzo MJ. The role of pictures in improving health communication: a review of research on attention, comprehension, recall and adherence. Pat Edu Coun. 2006;61(2):173–90.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Renato Giamberardino for refinement and editing of the article.

Funding

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

LeBrun, M., DiMuzio, J., Beauchamp, B. et al. Evaluating the Health Literacy Burden of Canada’s Public Advisories: A Comparative Effectiveness Study on Clarity and Readability. Drug Saf 36, 1179–1187 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-013-0117-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-013-0117-8