Abstract

Background

During sepsis, optimal plasma antibiotic concentrations are mandatory. Modifications of pharmacokinetic parameters could lead to low drug concentrations and therefore, insufficient therapeutic levels.

Objective

The aim of this study was to build a population pharmacokinetic model for cefotaxime and its metabolite desacetylcefotaxime in order to optimize individual dosing regimens for critically ill children.

Methods

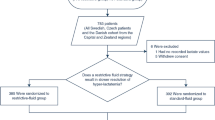

All children aged < 18 years, weighing more than 2.5 kg, and receiving intermittent cefotaxime infusions were included in this study. Cefotaxime and desacetylcefotaxime were quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography. Pharmacokinetics were described using the non-linear mixed-effect modeling software MONOLIX, and Monte Carlo simulations were used to optimize dosing regimen in order to maintain serum concentrations above the target concentration (defined at 2 mg·L−1) throughout the dosing interval.

Results

We included 49 children with a median (range) postnatal age of 23.7 (0.2–229) months, and median body weight (range) of 10.9 (2.5–68) kg. A one-compartment model with first-order elimination adequately described the data. Median (range) values for cefotaxime clearance, desacetylcefotaxime clearance, and volume of distribution were 0.97 (0.3–7.1) L·h−1, 3.2 (0.6–16.3) L·h−1, and 0.3 (0.2–0.41) L·kg−1, respectively. Body weight and postnatal age were statistically significant covariates. Cefotaxime-calculated residual concentrations were low, and no patient succeeded in attaining the target. Unlike intermittent administration, a dosing regimen of 100 mg·kg−1·day−1 administered by continuous infusion provided a probability of target attainment of 100%, regardless of age and weight.

Conclusions

Standard intermittent cefotaxime dosing regimens in critically ill children are not adequate to reach the target. We showed that, for the same daily dose, continuous infusion was the only administration that enabled the target to be attained, for children over 1 month of age. As continuous administration is achievable in the pediatric intensive care unit, it should be considered for clinical practice.

Trial registration number

Registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT02539407.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Spyridis N, Syridou G, Goossens H, Versporten A, Kopsidas J, Kourlaba G, et al. Variation in paediatric hospital antibiotic guidelines in Europe. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:72–6.

Amadeo B, Zarb P, Muller A, Drapier N, Vankerckhoven V, Rogues A-M, et al. European Surveillance of Antibiotic Consumption (ESAC) point prevalence survey 2008: paediatric antimicrobial prescribing in 32 hospitals of 21 European countries. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:2247–52.

Versporten A, Bielicki J, Drapier N, Sharland M, Goossens H. The Worldwide Antibiotic Resistance and Prescribing in European Children (ARPEC) point prevalence survey: developing hospital-quality indicators of antibiotic prescribing for children. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:1106–17.

Wise R, Wills PJ, Andrews JM, Bedford KA. Activity of the cefotaxime (HR756) desacetyl metabolite compared with those of cefotaxime and other cephalosporins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980;17:84–6.

Drusano GL. Antimicrobial pharmacodynamics: critical interactions of “bug and drug”. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:289–300.

Huttner A, Harbarth S, Hope WW, Lipman J, Roberts JA. Therapeutic drug monitoring of the β-lactam antibiotics: what is the evidence and which patients should we be using it for? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:3178–83.

Thakkar N, Salerno S, Hornik CP, Gonzalez D. Clinical pharmacology studies in critically ill children. Pharm Res. 2017;34:7–24.

Blot SI, Pea F, Lipman J. The effect of pathophysiology on pharmacokinetics in the critically ill patient: concepts appraised by the example of antimicrobial agents. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;77:3–11.

Udy AA, Roberts JA, Lipman J. Clinical implications of antibiotic pharmacokinetic principles in the critically ill. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:2070–82.

Leroux S, Roué J-M, Gouyon J-B, Biran V, Zheng H, Zhao W, et al. A population and developmental pharmacokinetic analysis to evaluate and optimize cefotaxime dosing regimen in neonates and young infants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:6626–34.

Kearns GL, Young RA. Pharmacokinetics of cefotaxime and desacetylcefotaxime in the young. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;22:97–104.

Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:2–8.

Schwartz G, Brion L, Spitzer A. The use of plasma creatinine concentration for estimating glomerular filtration rate in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Clin N Am. 1987;34:571–90.

Food and Drug Administration. Professional drug information. 2017. https://www.drugs.com/pro/cefotaxime.html. Accessed 1 May 2017.

Lüthy R, Münch R, Blaser J, Bhend H, Siegenthaler W. Human pharmacology of cefotaxime (HR 756), a new cephalosporin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;16:127–33.

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Antimicrobial wild type distributions of microorganisms. https://mic.eucast.org/Eucast2/SearchController/search.jsp?action=performSearch&BeginIndex=0&Micdif=mic&NumberIndex=50&Antib=44&Specium=-1. Accessed 1 Apr 2017.

Doerr BI, Glomot R, Kief H, Kramer M, Sakaguchi T. Toxicology of cefotaxime in comparison to other cephalosporins. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1980;6:79–82.

LeFrock JL, Prince RA, Leff RD. Mechanism of action, antimicrobial activity, pharmacology, adverse effects, and clinical efficacy of cefotaxime. Pharmacotherapy. 1982;2:174–84.

Ahsman MJ, Wildschut ED, Tibboel D, Mathot RA. Pharmacokinetics of cefotaxime and desacetylcefotaxime in infants during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:1734–41.

Kafetzis DA, Brater DC, Kanarios J, Sinaniotis CA, Papadatos CJ. Clinical pharmacology of cefotaxime in pediatric patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981;20:487–90.

van Zanten ARH, Oudijk M, Nohlmans-Paulssen MKE, van der Meer YG, Girbes ARJ, Polderman KH. Continuous vs. intermittent cefotaxime administration in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and respiratory tract infections: pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, bacterial susceptibility and clinical efficacy. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:100–9.

Turnidge JD. Pharmacodynamic (kinetic) considerations in the treatment of moderately severe infections with cefotaxime. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;22:57–69.

Anderson BJ, Holford NHG. Mechanism-based concepts of size and maturity in pharmacokinetics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48:303–32.

Baird-Lambert J, Doyle PE, Thomas D, Cvejic M, Buchanan N. Pharmacokinetics of cefotaxime in neonates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1984;13:471–7.

Udy AA, Roberts JA, Boots RJ, Paterson DL, Lipman J. Augmented renal clearance: implications for antibacterial dosing in the critically ill. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:1–16.

Brogden RN, Spencer CM. Cefotaxime. A reappraisal of its antibacterial activity and pharmacokinetic properties, and a review of its therapeutic efficacy when administered twice daily for the treatment of mild to moderate infections. Drugs. 1997;53:483–510.

Doluisio JT. Clinical pharmacokinetics of cefotaxime in patients with normal and reduced renal function. Rev Infect Dis. 1982;4:S333–45.

Avedissian SN, Bradley E, Zhang D, Bradley JS, Nazer LH, Tran TM, et al. Augmented renal clearance using population-based pharmacokinetic modeling in critically ill pediatric patients. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18(9):e388–94. doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000001228.

McKinnon PS, Paladino JA, Schentag JJ. Evaluation of area under the inhibitory curve (AUIC) and time above the minimum inhibitory concentration (T>MIC) as predictors of outcome for cefepime and ceftazidime in serious bacterial infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31:345–51.

Vincent J-L, Rello J, Marshall J, Silva E, Anzueto A, Martin CD, et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA. 2009;302:2323–9.

Mehrotra R, De Gaudio R, Palazzo M. Antibiotic pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations in critical illness. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:2145–56.

Taccone FS, Laterre P-F, Dugernier T, Spapen H, Delattre I, Wittebole X, et al. Insufficient β-lactam concentrations in the early phase of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care. 2010;14:R126.

Jacobs RF, Darville T, Parks JA, Enderlin G. Safety profile and efficacy of cefotaxime for the treatment of hospitalized children. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:56–65.

Gupta VD. Stability of cefotaxime sodium after reconstitution in 0.9% sodium chloride injection and storage in polypropylene syringes for pediatric use. Int J Pharm Compd. 2002;6:234–6.

Walker MC, Lam WM, Manasco KB. Continuous and extended infusions of β-lactam antibiotics in the pediatric population. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46:1537–46.

Gonçalves-Pereira J, Póvoa P. Antibiotics in critically ill patients: a systematic review of the pharmacokinetics of β-lactams. Crit Care. 2011;15:R206.

Roberts JA, Kirkpatrick CMJ, Roberts MS, Dalley AJ, Lipman J. First-dose and steady-state population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of piperacillin by continuous or intermittent dosing in critically ill patients with sepsis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;35:156–63.

Abdul-Aziz MH, Lipman J, Akova M, Bassetti M, De Waele JJ, Dimopoulos G, et al. Is prolonged infusion of piperacillin/tazobactam and meropenem in critically ill patients associated with improved pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic and patient outcomes? An observation from the Defining Antibiotic Levels in Intensive care unit patients (DALI) cohort. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:196–207.

Tamma PD, Putcha N, Suh YD, Van Arendonk KJ, Rinke ML. Does prolonged β-lactam infusions improve clinical outcomes compared to intermittent infusions? A meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:181.

Abhilash B, Tripathi CD, Gogia AR, Meshram GG, Kumar M, Suraj B. Variability in plasma concentration of cefotaxime in critically ill patients in an Intensive Care Unit of India and its pharmacodynamic outcome: a nonrandomized, prospective, open-label, analytical study. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2016;7:15–21.

Jones RN. Cefotaxime and desacetylcefotaxime antimicrobial interactions. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1995;22:19–33.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the PICU team (physicians and nurses) who included the children and realized the samples, making this work possible. They also thank the Pharmacology Laboratory of the Cochin Teaching Hospital, which analyzed the samples. Agathe Béranger is currently receiving a grant from the Agence Régionale de Santé Ile-de-France, for 1 year of research, as a fellow in the EA7323.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Agathe Béranger, Mehdi Oualha, Saïk Urien, Mathieu Genuini, Sylvain Renolleau, Radia Aboura, Déborah Hirt, Claire Heilbronner, Julie Toubiana, Jean-Marc Tréluyer, and Sihem Benaboud declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research study did not receive funds or support from any sources.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all parents of the children included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

40262_2017_602_MOESM2_ESM.tif

Supplementary Fig. 1 Description of the pharmacokinetic model. IV 30 min shows the intravenous infusion over 30 min of the CTX. VCTX and VD-CTX are the volume of distribution for the parent and the metabolite respectively. CL10 and CL20 are the elimination clearance for the parent and the metabolite respectively. CL12 is the metabolite formation clearance. (TIFF 201 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Béranger, A., Oualha, M., Urien, S. et al. Population Pharmacokinetic Model to Optimize Cefotaxime Dosing Regimen in Critically Ill Children. Clin Pharmacokinet 57, 867–875 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-017-0602-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-017-0602-9