Abstract

Background

Tranexamic acid (TXA) effectively reduces blood loss and transfusion requirements during craniofacial surgery. The pharmacokinetics of TXA have not been fully characterized in paediatric patients and dosing regimens remain diverse in practice. A mixed-effects population analysis would characterize patient variability and guide dosing practices.

Objective

The objective of this study was to conduct a population pharmacokinetic analysis and develop a model to predict an effective TXA dosing regimen for children with craniosynostosis undergoing cranial remodelling procedures.

Methods

The treatment arm of a previously reported placebo-controlled efficacy trial was analysed. Twenty-three patients with a mean age 23 ± 19 months received a TXA loading dose of 50 mg/kg over 15 min at a constant rate, followed by a 5 mg/kg/h maintenance infusion during surgery. TXA plasma concentrations were measured and modelled with a non-linear mixed-effects strategy using Monolix 4.1 and NONMEM® 7.2.

Results

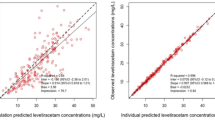

TXA pharmacokinetics were adequately described by a two-compartment open model with systemic clearance (CL) depending on bodyweight (WT) and age. The apparent volume of distribution of the central compartment (V1) was also dependent on bodyweight. Both the inter-compartmental clearance (Q) and the apparent volume of distribution of the peripheral compartment (V2) were independent of any covariate. The final model may be summarized as: CL (L/h) = [2.3 × (WT/12)1.59 × AGE–0.0934] × eη1, V1 (L) = [2.34 × (WT/12)1.4] × eη2, Q (L/h) = 2.77 × eη3 and V2 (L) = 1.53 × eη4, where each η corresponds to the inter-patient variability for each parameter. No significant correlation was found between blood volume loss and steady-state TXA concentrations. Based on this model and simulations, lower loading doses than used in the clinical study should produce significantly lower peak concentrations while maintaining similar steady-state concentrations.

Conclusions

A two-compartment model with covariates bodyweight and age adequately characterized the disposition of TXA. A loading dose of 10 mg/kg over 15 min followed by a 5 mg/kg/h maintenance infusion was simulated to produce steady-state TXA plasma concentrations above the 16 μg/mL threshold. This dosing scheme reduces the initial high peaks observed with the larger dose of 50 mg/kg over 15 min used in our previous clinical study.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Chadduck W. Craniosynostosis. In: Cheek WR, Marlin AE, McLone DG, editors. Pediatric neurosurgery. 3rd ed. Houston: W.B. Saunders Company; 1994. p. 111–23.

Reiner D. Intracranial pressure in craniosynostosis: pre- and postoperative recordings, correction with functional results. In: Edgerton M, Baltimore JS, editors. Scientific foundation and surgical treatment of craniosynostosis. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1989. p. 263–9.

Vamvakas EC. Long-term survival rate of pediatric patients after blood transfusion. Transfusion. 2008;48:2478–80.

Czerwinski M, Hopper RA, Gruss J, Fearon JA. Major morbidity and mortality rates in craniofacial surgery: an analysis of 8101 major procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:181–6.

Phillips RJ, Mulliken JB. Venous air embolism during a craniofacial procedure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;82:155–9.

Faberowski LW, Black S, Mickle JP. Blood loss and transfusion practice in the perioperative management of craniosynostosis repair. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 1999;11:167–72.

Buntain SG, Pabari M. Massive transfusion and hyperkalaemic cardiac arrest in craniofacial surgery in a child. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1999;27:530–3.

Williams GD, Ellenbogen RG, Gruss JS. Abnormal coagulation during pediatric craniofacial surgery. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2001;35:5–12.

Ririe DG, Lantz PE, Glazier SS, Argenta LC. Transfusion-related acute lung injury in an infant during craniofacial surgery. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1003–6.

Tuncbilek G, Vargel I, Erdem A, Mavili ME, Benli K, Erk Y. Blood loss and transfusion rates during repair of craniofacial deformities. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16:59–62.

Stricker PA, Shaw TL, Desouza DG, Hernandez SV, Bartlett SP, Friedman DF, et al. Blood loss, replacement, and associated morbidity in infants and children undergoing craniofacial surgery. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;20:150–9.

Goobie SM, Meier PM, Pereira LM, McGowan FX, Prescilla RP, Scharp LA, et al. Efficacy of tranexamic acid in pediatric craniosynostosis surgery: a double-blind placebo controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2011;114(4):862–71.

Dadure C, Sauter M, Bringuier S, Bigorre M, Raux O, Rochette A, et al. Intraoperative tranexamic acid reduces blood transfusion in children undergoing craniosynostosis surgery: a randomized, double-blind study. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:856–61.

Dunn CJ, Goa KL. Tranexamic acid: a review of its use in surgery and other indications. Drugs. 1999;57:1005–32.

Reid R, Zimmerman A, Laussen P, Mayer J, Gorlin J, Borrows F. The efficacy of tranexamic acid versus placebo in decreasing blood loss in pediatric patients undergoing repeat cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:990–6.

Fiechtner BK, Nuttall GA, Johnson ME, Dong Y, Sujirattanawimol N, Oliver WC, et al. Plasma tranexamic acid concentrations during cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:1131–6.

Sethna NF, Zurakowski D, Brustowicz RM, Bacsik J, Sullivan LJ, Shapiro F. Tranexamic acid reduces intraoperative blood loss in pediatric patients undergoing scoliosis surgery. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:727–32.

Eaton MP. Antifibrinolytic therapy in surgery for congenital heart disease. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:1087–100.

Horrow JC, Van Riper DF, Strong MD, Grunewald KE, Parmet JL. The dose-response relationship to tranexamic acid. Anesthesiology. 1995;82:383–92.

Murkin JM, Falter F, Granton J, Young B, Burt C, Chu M. High-dose tranexamic acid is associated with nonischemic clinical seizures in cardiac surgical patients. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:350–3.

Ngaage DL, Bland JM. Lessons from aprotinin: is the routine use and inconsistent dosing of tranexamic acid prudent? Meta-analysis of randomised and large matched observational studies. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37:1375–83.

Breuer T, Martin K, Wilhelm M, Wiesner G, Schreiber C, Hess J, et al. The blood sparing effect and the safety of aprotinin compared to tranexamic acid in paediatric cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;35:167–71.

Martin K, Breuer T, Gertler R, Hapfelmeier A, Schreiber C, Lange R, et al. Tranexamic acid versus varepsilon-aminocaproic acid: efficacy and safety in paediatric cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;39:892–7.

Soslau G, Horrow J, Brodsky I. Effect of tranexamic acid on platelet ADP during extracorporeal circulation. Am J Hematol. 1991;38:113–9.

Eriksson O, Kjellman H, Pilbrant A, Schannong M. Pharmacokinetics of tranexamic acid after intravenous administration to normal volunteers. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1974;7:375–80.

Pilbrant A, Schannong M, Vessman J. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of tranexamic acid. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;20:65–72.

Puigdellivol E, Carral ME, Moreno J, Pla-Delfina JM, Jane F. Pharmacokinetics and absolute bioavailability of intramuscular tranexamic acid in man. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1985;23:298–301.

Dowd NP, Karski JM, Cheng DC, Carroll JA, Lin Y, James RL, et al. Pharmacokinetics of tranexamic acid during cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:390–9.

Mandema JW, Verotta D, Sheiner LB. Building population pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic models: I. Models for covariate effects. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1992;20:511–28.

Wahlby U, Jonsson EN, Karlsson MO. Assessment of actual significance levels for covariate effects in NONMEM. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2001;28:231–52.

Parke J, Holford NH, Charles BG. A procedure for generating bootstrap samples for the validation of nonlinear mixed-effects population models. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 1999;59:19–29.

Hill SA. Pharmacokinetics of drug infusions. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2004;4(3):76–80.

Roberts I, Kawahara T. Proposal for the inclusion of tranexamic acid (anti‐fibrinolytic – lysine analogue) in the WHO model list of essential medicines. WHO EML – Tranexamic Acid – June 2010. http://www.who.int/selection_medicines/committees/expert/17/application/tranexamic/en/index.html. Accessed 19 Dec 2012.

Andersson L, Nilsoon IM, Colleen S, Granstrand B, Melander B. Role of urokinase and tissue activator in sustaining bleeding and the management thereof with EACA and AMCA. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1968;146:642–58.

Iribarren JL, Jimenez JJ, Hernandez D, Brouard M, Riverol D, Lorente L, et al. Postoperative bleeding in cardiac surgery: the role of tranexamic acid in patients homozygous for the 5G polymorphism of the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene. Anesthesiology. 2008;108:596–602.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goobie, S.M., Meier, P.M., Sethna, N.F. et al. Population Pharmacokinetics of Tranexamic Acid in Paediatric Patients Undergoing Craniosynostosis Surgery. Clin Pharmacokinet 52, 267–276 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-013-0033-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-013-0033-1