Abstract

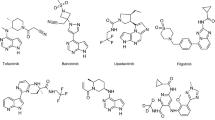

Cytokines, many of which signal through the JAK–STAT (Janus kinase–Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription) pathway, play a central role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Currently three JAK inhibitors have been approved for clinical use in USA and/or Europe: tofacitinib for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and ulcerative colitis, baricitinib for rheumatoid arthritis, and ruxolitinib for myeloproliferative neoplasms. The clinical JAK inhibitors target multiple JAKs at high potency and current research has focused on more selective JAK inhibitors, almost a dozen of which currently are being evaluated in clinical trials. In this narrative review, we summarize the status of the pan-JAK and selective JAK inhibitors approved or in clinical trials, and discuss the rationale for selective targeting of JAKs in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors target multiple cytokines simultaneously and present a viable treatment option in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Currently three pan-JAK inhibitors, tofacitinib (rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ulcerative colitis), baricitinib (rheumatoid arthritis), and ruxolitinib (myeloproliferative neoplasms), have been approved for clinical use. |

Recent research has focused on the development of selective JAK inhibitors as inhibition of specific JAK kinase may decrease adverse effects, and thus increase safety and efficacy. |

Phase II clinical trials of moderately selective JAK inhibitors demonstrate efficacy and adverse effects comparable to pan-JAK inhibitors but more data are needed, especially on highly selective inhibitors, to define the potential of selective JAK targeting in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. |

1 Introduction

Cytokines play pivotal roles in essential cellular functions such as proliferation, invasion, survival, inflammation, and immunity, and thereby have a central role in the pathogenesis of immunological diseases and cancer, either through their normal functions or due to deregulated signaling. Inhibition of cytokine functions by, for example, monoclonal antibodies against cytokines or their receptors have been successfully used for the reduction of chronically elevated cytokine signaling and uncontrolled cytokine effects. In recent years there has been growing interest towards modulating the key intracellular components of cytokine signaling, especially the Janus kinase (JAK) family of non-receptor tyrosine kinases that transduce signals from multitude of cytokines and growth factors [1]. Presently, three JAK inhibitors are approved for clinical use and almost a dozen others are in clinical trials for the treatment of autoimmune diseases and hematopoietic disorders.

In mammals, the JAK–STAT (Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription) pathways are constituted of four JAK kinases (JAK1–3 and tyrosine kinase 2 [TYK2]) and seven STATs (STAT1–6, including homologs STAT5a and STAT5b). The signaling cascade is initiated by cytokine binding to its receptor and subsequent association/rearrangement of the receptor subunits, which enables JAK activation by trans-phosphorylation (Fig. 1). Once activated, JAKs phosphorylate the receptors, allowing STATs to bind to the receptor and become phosphorylated by JAKs. The phosphorylated STATs (pSTATs) form either homo- or heterodimers, which translocate into the nucleus where they bind their cognate promoter elements to regulate transcription of target genes. The flexibility in the STAT dimerization increases the range of gene-specific binding sites as well as contributing to the efficiency of the nuclear translocation, and thus to variation in biological responses [2, 3]. Each cytokine receptor recruits and employs a specific combination of JAK kinases, which has important implications in therapeutic targeting of JAKs in various disease entities (Fig. 2) [4].

Schematic presentation of the JAK–STAT (JAK1/JAK3–STAT5) pathway. The panel on the left presents the inhibition mechanism of an ATP-competitive JAK inhibitor. Inhibitor that competes with ATP blocks nucleotide binding and inhibits kinase activity and the phosphorylation of downstream effectors. ATP adenosine triphosphate, JAK Janus kinase, STAT Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcription, γc common gamma chain, P phosphate.

Cytokines (with particular JAKs that mediate the signaling indicated in parentheses) involved in T cell differentiation and function. As the antigen presenting cell engages with the T cell receptor, several cytokines are released to promote the differentiation of various T cell subtypes. Differentiated T cells produce cytokines that contribute to various immune responses and are implicated in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. AA alopecia areata, AD atopic dermatitis, AS ankylosing spondylitis, CD Crohn’s disease, IFN interferon, IL interleukin, JAK Janus kinase, RA rheumatoid arthritis, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus, TGFβ transforming growth factor-β, Th T helper cell, Treg regulatory T cell, TSLP thymic stromal lymphopoietin, TYK tyrosine kinase, UC ulcerative colitis

JAKs are structurally conserved and consist of four domains: N-terminal FERM (4.1 protein, ezrin, radixin, moesin) together with an Src Homology 2 (SH2)-like domain form the major receptor interaction moiety [5]. This is followed by a pseudokinase domain (JAK homology 2 [JH2]), and a C-terminal tyrosine kinase domain (JAK homology 1 [JH1]), which is an active kinase that phosphorylates target proteins on tyrosine residues. JH2 is the most characteristic feature of JAKs and it shows sequence homology to classical protein kinases but lacks key catalytic residues. JH2 has an important regulatory function in controlling JAK activity in the absence of cytokine but also in inducing signaling upon cytokine binding [6, 7]. JH2 is a mutational hotspot for clinical JAK mutations causing immunologic and neoplastic diseases [4, 8]. Characteristics of the structural features of pseudokinases are reviewed elsewhere, e.g., by Hammarén et al. [9]. Here we discuss the cytokine signaling pathways in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases and summarize the efficacy and safety of the existing clinical JAK inhibitors as well as the more selective JAK inhibitors currently in clinical trials.

2 Inflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases: Rationale for Janus Kinase (JAK) Targeting

Inflammatory and autoimmune diseases are chronic diseases whose initiation is influenced by both genetic and environmental factors and which are characterized by disease flares and remission periods. Cytokines play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of the inflammatory diseases, each of which show typical cytokine profiles (see Table 1). Different T cell subtypes become activated by certain cytokines in initiation of the disease, and drive the inflammation through cytokine production (Fig. 2). Additionally, a network of lymphoid and myeloid cells also contribute to the cytokine profiles. For example, natural killer (NK) cells and macrophages secrete proinflammatory cytokines, attract and activate other immune cells, whereas myeloid cells (including dendritic cells) may induce overproduction of type I interferons (IFNs) leading to the production of antibodies by B cells [10,11,12]. Therefore, it is not surprising that in the recent decade a number of antibodies targeting cytokines or their receptors have entered the clinic (Table 1). The success of biologic drugs validates a number of cytokine signaling pathways, many of which signal through JAKs and STATs, as relevant drug targets for small-molecule inhibitors. Currently there are no curative therapies for inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, although clinical remission has become a realistic target, e.g., in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The story of JAKinibs started after the characterization of JAK3 as a key regulator of lymphocytes and the development of tofacitinib. The promising results of tofacitinib on efficacy and safety spurred several other drug development programs on different JAKs, and the identification of somatic activating mutations, particularly in JAK2, further stimulated the development activities. Currently, three JAK inhibitors, tofacitinib, baricitinib, and ruxolitinib, have been approved for clinical use in the USA and Europe. All these drugs represent the first-generation adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-competitive JAKinibs and target the JH1 tyrosine kinase domain in an active conformation. The highly conserved structure of the ATP-binding pocket in the active conformation makes it challenging to develop specific inhibitors, and subsequently the first-generation JAKinibs target several JAKs.

2.1 Rheumatoid Arthritis

RA is a chronic inflammatory disease primarily of joints. Common symptoms include joint swelling, pain, and stiffness, but it may lead to permanent joint destruction and deformity. The exact cause of RA remains unclear; however, multiple risk factors including genetic background, smoking, silica, or textile dust inhalation, periodontal disease, and mucosal microbiome have been identified [13]. Cytokines including tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha, interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-7, IL-15, IL-17, IL-18, IL-21, IL-23, IL-32, IL-33, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) have important roles in pathogenesis of RA [14]. A folic acid antagonist methotrexate that inhibits lymphocyte proliferation and the production of proinflammatory cytokines by suppression of enzymes critical for, for example, DNA and RNA synthesis is a well-established first-line treatment for RA [15]. Methotrexate has also been reported to modulate JAK–STAT signaling, i.e., to reduce pSTAT1 and pSTAT5 levels, in human cells [16].

TNF, IL-1, and IL-6 signaling pathways have successfully been targeted with biological drugs in RA (Table 1). IL-6 signals through JAK1, JAK2, and/or TYK2 (Fig. 2), which phosphorylate and activate STAT3 [17]. The success of the IL-6 inhibitor tocilizumab validates JAK1, JAK2, and TYK2 as important players in RA pathogenesis and as viable drug targets. As the biologics are large proteins, they may cause immunogenicity and require either intravenous infusion or subcutaneous injection for dosing; thus, an interest in small-molecule inhibitors of the cytokine signaling pathways has risen in recent decade. The JAK3/JAK1 inhibitor tofacitinib was the first JAK inhibitor approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (November 2012) and European Medicines Agency (EMA) (March 2017) for the treatment of moderate to severe active RA in patients who had an inadequate response to methotrexate. Tofacitinib as a monotherapy (at a dosage of 5 mg twice daily) and in combination with methotrexate is efficacious and the clinical responses have proven similar to TNF antagonists [18, 19]. Tofacitinib has a rapid onset of action indicated by significantly higher American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20% response criteria (ACR20) in 2–4 weeks compared with placebo in combination therapy with methotrexate [18, 20]. Roughly 75% of patients obtain ACR20 response and 55% obtain ACR 50% response criteria (ACR50) in tofacitinib monotherapy in 6 months and the effects are generally sustained for at least 72 months [21, 22]. Tofacitinib treatment, although generally well-tolerated, may cause infections that are typical also for biologics, decreases in CD4+ T cell count, elevated cholesterol levels, headache, and slight reversible increases in serum creatinine levels [21, 23, 24].

The JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor baricitinib was the second JAK inhibitor approved for clinical use in RA, first (February 2017) by the EMA and more recently (June 2018) by the FDA. Baricitinib is a structural analog of ruxolitinib, a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor approved for treatment of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), which is also in clinical trials for RA and a number of other autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. In methotrexate background, baricitinib has been proven to be superior to placebo and the TNF antagonist adalimumab for patients with inappropriate response to methotrexate [25]. The improvements in the baricitinib arm were statistically significant at week 1 compared with placebo and at week 2–4 compared with adalimumab, and the measures of efficacy were maintained or improved through week 52 [25]. Adverse events were more frequent in the baricitinib and adalimumab arms than in placebo arms, and similar between the baricitinib and adalimumab arms [25]. Very common (≥ 1/10) adverse effects for baricitinib are upper respiratory tract infections and hypercholesterolemia, whereas common (≥ 1/100 to < 1/10) adverse effects include other infections (herpes zoster, herpes simplex, urinary tract infections, gastroenteritis), thrombocytosis, nausea, and hepatobiliary disorders [26]. Baricitinib at approved dosages (2 and 4 mg once daily) has not been indicated to cause anemia in RA patients [27], which is an interesting finding for an inhibitor of JAK2 that has a major role in hematopoiesis.

2.2 Inflammatory Bowel Disease

IBD is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the colon and small intestine that causes epithelial injury. The impact of IBD on quality of life is typically high, with symptoms including diarrhea, abdominal cramping, anemia, weight loss, and fatigue. IBD comprises independent clinical entities of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), which have differing pathological features, including risk factors. For example, smoking is a risk factor for CD, whereas it is protective for UC [28]. Furthermore, CD and UC have characteristic cytokine profiles [29, 30]. The serum level of IL-8 has been reported as being elevated equally in CD and UC patients, whereas increases in IFN-y, IL-6, and IL-7 are specific for CD, and increases in eotaxin, growth-regulated oncogene (GRO), and TNF-α are specific for UC [30]. Furthermore, transcription-level characterization of T helper (Th) 2- and Th17-related cytokine profiles in inflamed mucosal samples of CD and UC patients showed increases in IL-12 (p40), IL-18, IL-21, and IL-27 for both CD and UC [29]. Levels of IL-17, IL-23, and IL-32 are elevated specifically in CD, whereas IL-5, IL-13, IL-15, and IL-33 are elevated in UC patient samples [29]. The cytokine profiles support the hypothesis of CD being associated with Th1/Th17 immune responses (IFN-γ, IL-17, IL-23) and UC with Th2 (IL-5, IL-13, IL-33) (Fig. 2).

Conventional therapies for the treatment of IBD include immunosuppressives, namely methotrexate, azathioprine, mercaptopurine, aminosalicylates, and corticosteroids [31]. In addition, TNF inhibitors are commonly prescribed as first-line therapies for IBD and the treatment depends on severity of disease [32]. A number of biologics targeting IFN-β, IFN-γ, TGF-β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-11, IL-12/IL-23, IL-13, and IL-17 signaling have been evaluated in clinical trials for IBD [33], many of which (IFN-β, IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-11) resulted in limited or no efficacy [34,35,36,37]. The IL-6 antagonist tocilizumab was suggested to have a clinical effect in active CD in a pilot study of 36 patients [38]. Furthermore, ustekinumab, which targets IL-12/IL-23 signaling, has in multiple clinical trials proven efficacious in CD patients who had inadequate response for immunomodulators, corticosteroids, or TNF antagonists [39], and was approved by the FDA for clinical use. IL-6 signals through JAK1/JAK2/TYK2 and IL-12/23 through JAK2/TYK2 (Fig. 2), and therefore targeting these JAKs could result in a favorable clinical outcome in the treatment of IBD.

Tofacitinib (10 mg twice daily) was recently (May 2018) approved for the treatment of moderate or severe active UC by the FDA. It induced remission at the accepted dose at week 8 for 18.5% of moderate to severe active UC patients (8.2% for placebo), and at week 52 for 40.6% of patients (11.1% for placebo) [40]. Tofacitinib also improved health-related quality of life as early as on week 4 and the effect was sustained for at least 52 weeks [41]. The safety profile was mainly similar to that in RA patients, but the risks of lymphoma and malignancies were slightly elevated [40]. Tofacitinib failed to meet its efficacy end-points (proportion of clinical responders and clinical remission at week 4) in a pilot study for patients with CD, although some indications of biological activity were obtained, and response rate in placebo group was unexpectedly high [42].

2.3 Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis

Psoriasis vulgaris, a chronic plaque psoriasis, is an autoimmune disease characterized by red, itchy, and scaly skin lesions located most commonly in the knees, elbows, scalp, and trunk. The disease severity is generally characterized by the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), which combines the assessment of the severity of lesions and the area affected into a single score. In clinical trials, PASI is usually presented as a percentage response rate, e.g., PASI 50, PASI 75, PASI 90, PASI 100. Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) develops for approximately 20–30% of psoriasis patients [43, 44] but may also occur in non-psoriatic patients. Like RA, PsA causes joint stiffness, swelling, and pain but is specifically associated with skin and/or nail lesions. Co-morbidities, e.g., diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, depression, hypertension, cancer, and/or IBD, are common for psoriasis and PsA patients [43]. Pathogenesis of psoriasis arises from dysregulated functions of immune cells, mainly dendritic cells and Th17 and Th1, and keratinocyte proliferation/differentiation [45]. Psoriasis is associated with increased serum levels of TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-18, and IL-22 despite the patient’s age or gender, whereas increased IL-17 is correlated with psoriasis in men [46].

A typical first-line therapy for psoriasis is treatment with topical corticosteroids, whereas phototherapy and systemic non-biological therapies methotrexate or ciclosporin (cyclosporine) are considered as second-/third-line therapies [47]. Biologics targeting TNF, IL-12/IL-23, and IL-17 signaling have proven efficacious, and are in clinical use for treatment of psoriasis and PsA [48]. The most recent additions to the family of biologic drugs are antibodies that specifically target IL-23 without affecting IL-12 signaling. A phase II randomized trial revealed superiority of an IL-23 monoclonal antibody risankizumab to the IL-23/IL-12 inhibitor ustekinumab in treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: PASI 90 at week 12 was 77% for risankizumab (pooled 90 and 180 mg dose arms) versus 40% for ustekinumab [49]. This indicates that the specific inhibition of IL-23 signaling is meaningful in the treatment of psoriasis and the simultaneous inhibition of IL-12 might decrease the effectiveness [50]. IL-23 blockage effectively suppresses the expression of IL-17 and its regulated genes in psoriatic skin lesions [51, 52]. IL-23 signals through JAK2 and TYK2, which could therefore be valid targets for the treatment of psoriasis.

Tofacitinib has been approved for the treatment of PsA, whereas the FDA declined to approve the JAK inhibitor for psoriasis. Two similarly designed randomized phase III trials comparing tofacitinib versus placebo in moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis patients demonstrated the efficacy of oral tofacitinib, with the 10 mg twice daily (BID) being more efficacious than the 5 mg BID [53]. The treatment response was sustained for most of the patients through 2 years with no unexpected safety findings [54]. Serious adverse events were reported in 10% of patients and discontinuations due to adverse events in 11%, with no dependency of tofacitinib dose during 52 weeks [54]. Yet another phase III trial implies that the treatment response as well as the rate and nature of the adverse events of tofacitinib were similar to those of the TNF inhibitor etanercept [55]. The JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib has also been tested in clinical trials for moderate to severe psoriasis. A phase II study demonstrated significant improvements with baricitinib at doses of 8 and 10 mg once daily compared with placebo at 8 and 12 weeks [56]. Baricitinib was generally well-tolerated through the 24-week trial period. At 12 weeks, baricitinib treatment was reported to cause small dose-related decreases in neutrophil count and hemoglobin levels, as well as small increases in creatinine and lipoprotein levels [56]. JAK inhibitors have also been explored in psoriasis as topical treatments [57,58,59]. Topical ruxolitinib (1% and 1.5% cream twice daily) was observed to be pharmacologically active in psoriasis patients and to downregulate transcription of Th1 and Th17 cytokines in psoriatic skin lesions with no indications of systemic effects [58].

2.4 Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by highly pruritic, red, and swollen skin lesions. AD most often affects infants and small children, and is associated with other atopic/allergic diseases such as allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, allergic bronchial asthma, and food allergy [60]. Approximately 80% of AD patients have elevated serum IgE levels, which induces mast cell activation as well as recruitment and activation of Th2 cells, eosinophils, and basophils. Increased Th2 signaling via cytokines IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-31, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) has a central role in AD pathogenesis [60].

First-line treatment for AD is generally emollients and topical corticosteroids [61], and additionally an IL-4/IL-13 inhibitor dupilumab has been approved for clinical use in AD [62]. The key cytokines of AD signal through JAKs, which provides a rationale for AD treatment with JAK inhibitors. A phase II study was performed for topical tofacitinib in mild-to-moderate AD with promising results: Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) was significantly improved compared with vehicle in 1 week and pruritus in 2 days [63]. Safety and local tolerability of topical tofacitinib was comparable with vehicle [63]. Oral tofacitinib has been evaluated in a small study of six patients with moderate to severe AD with promising efficacy and no severe adverse effects [64]. Oral baricitinib has demonstrated efficacy in a recently reported phase II trial for moderate to severe AD [65]. The improvements in EASI-50 by baricitinib in 2 and 4 mg doses versus placebo were significant as early as at week 4 [65].

2.5 Ankylosing Spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory arthritis of the spine and sacroiliac joints that predominantly affects young men. The role of IL-17-expressing CD4+ T cells seems evident in the pathogenesis [66], although a recent report pointed out that increased IL-17 levels were only significant in male and not in female patients [67]. Numerous risk genes have been identified in AS, including IL-23 signaling related IL-23 receptor (IL-23R), IL-12 receptor (IL-12R), TYK2, and STAT3 variants [68,69,70].

Newly diagnosed AS patients are commonly treated with physical therapy and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [71]. Biologics targeting TNF and IL-17 signaling have been approved for clinical use in AS, whereas an anti-IL-23 biologic risankizumab failed to meet its primary endpoint in terms of efficacy, suggesting that IL-23 signaling alone is not a primary driver in pathogenesis [72]. Tofacitinib has been evaluated in phase II studies for clinical efficacy in patients with AS with promising results. The pan-JAK inhibitor in doses of 5 and 10 mg twice daily demonstrated significant improvements compared with placebo in clinical outcomes with minimal difference between the two tofacitinib doses [73]. No unexpected safety findings were observed [73].

2.6 Other Diseases

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease characterized by imbalanced regulation of Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells with increased plasma levels of IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, IL-17, IFN-γ, IFN-α, and B cell activating factor (BAFF), and decreased levels of IL-4 [74]. The symptoms of SLE include facial red rash, painful and swollen joints, fever, chest pain, hair loss, mouth ulcers, swollen lymph nodes, and fatigue. The BAFF inhibitor belimumab has been accepted for clinical use in SLE [75], and type I IFN antagonist anifrolumab is currently in phase III trials [76]. The activated cytokine signaling implies that SLE as well as alopecia areata (AA), in which Th1, Th2, Th17 and/or Treg cells have been suggested to play roles in pathogenesis [77, 78], could benefit from certain biologics and JAK inhibitors but none has entered the clinics to date. A small pilot clinical trial in moderate to severe AA patients indicated significant scalp hair regrowth and improvement of AA for 75% of patients using ruxolitinib [79]. Baricitinib (4 mg dose) has proven clinically efficacious in reducing signs and symptoms of SLE in a phase II randomized placebo-controlled trial [80].

3 Selective JAK Inhibitors in the Pipeline

3.1 Illusion of Selectivity

The general characteristics of the JAK–STAT pathway are well-established but the exact molecular mechanism of JAK activation and downstream signaling in response to approximately 60 cytokines and hormones is still not exactly known. The various coupling patterns and hierarchical activation between JAKs in different receptors as well as the regulatory mechanisms are important for future pharmacological approaches but the traditional kinase inhibitors are still dominating JAKinib development, with the TYK2 JH2-targeting inhibitor being the only exception.

JAK inhibitors block downstream signaling of a variety of cytokines relevant for several physiological functions. Therefore, various adverse effects of JAK inhibitor treatment are expected, and were often predicted based on the function of JAKs. The bulk of the safety data concerning JAK inhibitors have arisen from tofacitinib trials. In general, the studies have shown an acceptable safety profile, with infection and cytopenias being the major adverse events [81,82,83]. The risk of infection, as a result of immunosuppression, has been shown to be similar to that observed with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), with the exception of varicella zoster virus infection risk, which is elevated in tofacitinib patients. The risk of cytopenias is due to the blockage of myelopoietic growth factor signaling, which occurs through JAK2. Indeed, cytopenias, such as neutropenia and anemia, have been observed as an adverse effect, but these have typically been mild at lower doses. An obvious, and serious, concern regarding long-term blocking of the JAK–STAT pathway is the risk of developing malignancies. Long-term studies with tofacitinib have, however, not shown an increased risk of cancer [21]. Other adverse effects of tofacitinib treatment include elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels during the first 1–3 months of treatment but these show stabilization thereafter and appear not to be related to higher risk of cardiovascular adverse events [84]. JAK inhibitors have also been linked to increased risk of gastric perforation and venous thromboembolism. However, the scale of the risk and a clear mechanism for these effects are not known [85, 86]. In addition, patients with RA, AS, psoriasis, and PsA already have an increased risk of thromboembolic events, further complicating the picture [87, 88].

Although the first-generation non-selective JAKinibs have proven to be efficacious in clinical trials and in the clinic in treating inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, adverse effects such as JAK2 inhibition-driven cytopenias have motivated the development of more JAK-specific compounds. This could be especially relevant when treating inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, which are not life-threatening and require a long duration of treatment. The caveat of improved selectivity is the possible reduction of efficacy as autoimmune diseases are characterized by imbalance of several cytokines (Table 1). In addition, achieving and measuring selectivity is a long-standing problem in kinase inhibitor discovery [89]. The promiscuity of kinase inhibitors arises from a highly conserved active site of protein kinases as well as their conserved phosphoryl transfer mechanism. Cellular ATP concentration is between 1 and 5 mM and kinases can have 1000-fold or even higher differences in their Michaelis-Menten constant (Km) for ATP [90]. Therefore, assay ATP concentration can have a large effect on potency measurements. Additional variation to potency measurements arise from assay technology, assay conditions (especially cations and kinase substrate), and construct selection (e.g., kinase domain vs. full-length enzyme). The development of JAK-selective inhibitors also pose additional challenges. The active JH1 domains of JAKs share a high structural similarity around the ATP binding site. Due to heterodimeric pairing of JAKs in certain cytokine signaling pathways, the dominant role of one JAK over another leads to different selectivity profiles in different cytokine pathways [91]. Therefore, it is not surprising that discrepancies between biochemical and cellular potencies of JAK inhibitors have been reported [92]. A comparison of the reported potencies of JAKinibs in clinical trials against inflammatory and autoimmune diseases is presented in Table 2. When evaluating the potency of inhibitors, these difficulties in measurements need to be taken into account. In Sects. 3.2–3.4 we review JAK1-, JAK3-, and TYK2-targeting inhibitors currently in clinical trials against autoimmune diseases. The comparison of the effects of JAK inhibitors against RA and psoriasis from phase II trials are listed in Table 3.

3.2 JAK1-Targeting Inhibitors

JAK1 functions in several signaling pathways, and due to its wide spectrum of functions it is not surprising that JAK1 knockout mice die shortly after birth due to deficiencies of lymphocyte development and failure to respond to several cytokines [93]. However, several gain-of-function JAK1 mutations have been found in patients with different types of acute lymphoblastic/myeloid leukemia and both gain-of-function and loss-of-function (frame-shift) JAK1 mutations occur in cancers [94,95,96,97].

JAK1-selective inhibitors target the broadest cytokine profile among JAKs. JAK1 signals with JAK2 via IFN-γ receptor, JAK3 through the gamma chain (γc) receptor (via cytokines IL-2, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15, and IL-21), and TYK2 via the IFN-α/β receptor and the receptors for the IL-10 family of cytokines. JAK1 also pairs with JAK2 and TYK2 to signal through glycoprotein (gp) 130-containing receptors (cytokines IL-6, IL-11, and IL-27). Therefore, one might not expect as favorable a safety profile with JAK1-selective compounds as with JAK3 inhibitors, for instance. JAK1 has also been suggested to dominate in IL-2-induced JAK1/JAK3 and IL-6-induced JAK1/JAK2/TYK2 signaling pathways, implying that selective JAK1 inhibition provides sufficient efficacy in treatment of various inflammatory diseases [98, 99]. However, selective JAK1 inhibitors still spare JAK2-dependent erythropoietin (EPO) and thrombopoietin (TPO) pathways responsible for adverse effects arising from JAK2 inhibition such as anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia.

Filgotinib (GLPG0634) was the first JAK1-selective JAKinib to reach clinical trials. It was developed from an in vitro JAK1 kinase domain screening hit via a combination of structure–activity relationship studies and structure-based design exploiting the differences in the active sites of JAK kinases. Filgotinib displayed ≈ 30-fold selectivity over JAK2 in whole-blood assays, was efficacious in a preclinical mouse model for arthritis [100], and was found not to interfere with JAK2 signaling in a phase I study [101]. Two phase II studies investigated filgotinib for the treatment for RA either as a monotherapy or in combination with methotrexate [102, 103]. In both studies filgotinib displayed dose-dependent clinical efficacy with an early onset of action. Filgotinib was well-tolerated, with infections being the most frequent adverse event. Increased hemoglobin was observed in both studies and was attributed to reduced inflammation as well as lack of JAK2 inhibition. HDL and LDL increases were observed, although, unlike with tofacitinib, the LDL:HDL ratio fell. A phase II clinical trial of filgotinib in CD has been completed [104], in which 47% of patients receiving filgotinib 200 mg once daily achieved clinical remission versus 23% on placebo. No change in LDL was observed, while HDL cholesterol increased, as did hemoglobin. Recently, results from two phase II studies of filgotinib for the treatment of PsA and AS were published [105, 106]. Consistent with previous trials, filgotinib displayed rapid onset of action and significantly improved signs and symptoms of the diseases in both studies. The safety profiles were similar to previous filgotinib studies as were laboratory parameters, including observed increases in HDL and hemoglobin levels. Currently, filgotinib is in phase III trials for UC, CD, and RA (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT03025308, NCT02914600, NCT02914535, NCT02914561, NCT02914522, NCT02873936, NCT02886728, and NCT02889796).

Upadacitinib (ABT-494) was developed as a JAK1-selective inhibitor by utilizing differences in the non-conserved interactions outside the active sites of JAK1 and JAK2. Upadacitinib displays 74-fold and 58-fold in vitro selectivity over JAK2 and JAK3, respectively [107]. Results of two phase II clinical studies with upadacitinib against RA with patients who did not respond to either methotrexate or TNF inhibitors have been reported [107, 108]. In both studies upadacitinib demonstrated fast response and efficacy as shown by significant differences in the ACR20 response rates compared with placebo as soon as at week 2 after the start of the treatment. Upadacitinib treatment led to dose-dependent elevation of LDL and HDL cholesterol levels, while the LDL:HDL ratio remained unchanged. Dose-dependent reduction in hemoglobin levels was also observed, suggesting the possibility of JAK2 inhibition, especially at higher doses. A recent phase III trial with upadacitinib for RA patients with inadequate response to conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs) showed similar results as the previous phase II studies [109]: upadacitinib displayed a fast onset of action and the patients showed improvements in clinical signs and symptoms of RA. LDL and HDL cholesterol levels increased and hematological parameters, such as hemoglobin, lymphocytes, and neutrophils, remained within the normal range over the course of the study. Currently, several phase II and III trials are ongoing with upadacitinib for several indications, such as RA, UC, CD, and PsA, with promising results, such as clinical remission, acquired from CD trials [110].

Itacitinib (INCB039110) is a JAK1-selective inhibitor with > 20-fold selectivity over JAK2 and > 100-fold selectivity over JAK3 and TYK2 [111, 112]. Accordingly, it has shown lack of activity in JAK2-dependent cell-based assays. Itacitinib has been potent in cellular assays relevant to psoriasis and efficacious in preclinical rat adjuvant-induced arthritis model [111]. Results from two phase II studies in psoriasis and RA demonstrated significant clinical improvements with itacitinib treatment in both cases. The adverse effect profile was similar to that of non-selective JAK inhibitors, such as infections and hypertriglyceridemia [111, 113].

Solcitinib (GSK2586184) was developed as a JAK1-selective inhibitor targeting the ATP-binding site of the kinase domain. It was found to be efficacious against moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in a phase II study [114]. In another phase II study of patients with moderate to severe SLE, solcitinib showed no significant effect in the interim analysis and the study was declared futile. Subsequently, the study was terminated due to eight serious adverse events, with six cases of elevated liver enzymes, two of whom were diagnosed with drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome [115]. Whether SLE or concomitant medications (five patients with elevated liver enzymes also received hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine, which can induce DRESS syndrome) predisposed patients to the adverse effects and what this means for the development of JAK1 inhibitors for SLE is still unclear. Shortly after, the development of solcitinib was discontinued due to discovery of statin (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor) drug–drug interactions (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02000453).

PF-04965842 was designed by modifying the tofacitinib scaffold and further improving the compound by structure-guided design for higher selectivity towards JAK1 [116]. In a phase II study for psoriasis, PF-04965842 improved symptoms and was generally well-tolerated [117]. The study was terminated early on due to changes in development priorities, but the treatment resulted in statistically significant reductions in PASI compared with placebo. Treatment with PF-04965842 resulted in decreases in the reticulocyte, neutrophil, and platelet counts, suggesting some JAK2 inhibition in the clinical setting. Currently, PF-04965842 is in phase III trials for AD (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT03575871, NCT03627767, NCT03349060, NCT03422822, and NCT03720470).

3.3 JAK3-Targeting Inhibitors

JAK3, together with its dimerization partner JAK1, has an important role in maintaining immune homeostasis. JAK3 binds to the common γc receptor, which drives the development of T cells, regulates the growth of B cells, and activates NK cell proliferation, among other functions [118,119,120]. Based on the salient role of JAK3 in the regulation of immune responses, it is considered to be a relevant target for immunosuppression [121]. The role of JAK3 is highlighted by the fact that mutations within the IL-7 receptor (IL-7R)–γc–JAK3 axis account for the majority of severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) cases. In addition to loss-of-function mutations, several types of leukemia and lymphomas arise from activating mutations in JAK3 and the excessive STAT activation they entail [122,123,124]. Because its expression is confined to hematopoietic cells, selective targeting of JAK3 in autoimmune diseases could escape the non-immunological adverse effects, e.g., neutropenia and anemia.

Decernotinib (VX-509) was developed via a structure-guided approach from an HTS screen hit and targets the kinase domain of JAK3. It displays five-fold in vitro selectivity towards JAK3 over the other JAKs and even higher selectivity in cellular assays [125]. Decernotinib has shown efficacy in an animal model for RA and inhibited T cell-mediated inflammatory processes in a mouse oxazolone-induced delayed-type hypersensitivity model [126]. Two phase II studies have been completed with decernotinib for RA: one in combination with methotrexate [127], the other in combination with a DMARD [128]. In both studies decernotinib significantly improved the symptoms compared with placebo. Infections as well as increases in liver transaminase, creatinine, and lipid levels were observed as adverse effects. Neutropenia was observed in patients in the methotrexate study, suggesting decernotinib might engage other JAKs also [129]. The major metabolite of decernotinib is a potent inhibitor of cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4, a major drug-metabolizing enzyme, which is involved in the metabolism of, for example, statins [130]. This drug–drug interaction might complicate the use of decernotinib, and currently there are no ongoing clinical trials with the compound.

Peficitinib (ASP015K) is pan-JAK inhibitor displaying moderate selectivity towards JAK3. In a 6-week phase IIa study of psoriasis, peficitinib displayed significant improvement in overall disease activity [131]. Peficitinib has also been tested against RA either as monotherapy [132] or in combination with methotrexate [133] or csDMARDs [134]. In these studies, peficitinib showed statistically significant reduction of RA symptoms with similar responses as seen with non-selective JAKinibs. Also, the adverse events were similar to those displayed by non-selective JAKinibs, e.g., neutropenia, but an increase rather than a decrease in hemoglobin was observed. In a recent phase IIb study for UC, peficitinib failed to show dose–response, although at higher doses it displayed a trend for increased rates of clinical response and remission as well as mucosal healing [135]. Currently, there are no ongoing peficitinib clinical trials for UC and its development status for this condition is uncertain.

PF-06651600 was developed by structure-guided design as a selective JAK3 inhibitor. It is the only covalent, irreversible JAK inhibitor in clinical trials and acts through a non-conserved cysteine (Cys909) in the JAK3 JH1 ATP pocket [136]. PF-06651600 is potent and highly selective inhibitor with negligible potency towards other JAKs at physiological ATP concentrations allowing a selective inhibition of signaling occurring though γc cytokines [137]. It has also been profiled against the kinome and revealed high selectivity at 1 µM concentration, the only off-targets being the TEC family of kinases, which share the cysteine in the same position in the active site as JAK3. PF-06651600 is currently in phase II clinical trials against RA, CD, UC, and AA. Whether the high selectivity of PF-06651600 translates into clinical efficacy and, more interestingly, a better side-effect profile, remains to be seen.

3.4 TYK2-Targeting Inhibitors

TYK2 was first considered mainly as a regulator of the IFN-α pathway [138], although TYK2−/− mice showed reduced but not abolished IFN-α/β signaling. The biological function of TYK2, however, appears to be broader in humans than in mice. While in mice TYK2 participates in IFN-α, IL-12, and IL-23 signaling, clinical data from patients have revealed that human TYK2 profoundly affects also signaling via IFN-γ, IL-6, and IL-10 (Fig. 2) [91, 121, 139, 140]. TYK2 forms dimers with JAK1 and JAK2, and it has been shown to be an important player against viral infections [140, 141]. In contrast to JAK1 and JAK2, TYK2 deficiency is not lethal, but the patient suffers from mycobacterial and viral infections [142]. The rationale for TYK2 inhibition in autoimmune diseases arises from antibody therapeutics that target TYK2 cytokine signaling pathways IL-12/IL-23, IFN-α, and IL-6 (Table 1).

PF-06700841 is described as an ATP-competitive selective TYK2/JAK1 inhibitor but selectivity data are not currently available. In a phase I dose-ranging study, PF-06700841 improved disease activity in patients with plaque psoriasis [143]. PF-06700841 was well-tolerated but led to decreases in reticulocytes and platelets indicating inhibition of JAK2. The compound is currently in phase II studies for CD, UC, AA, and plaque psoriasis (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT02969018, NCT03395184, NCT02958865, and NCT02974868).

JAK kinases are unique in the kinome (in addition to general control nonderepressible 2 [GCN2]) in that they possess both kinase and pseudokinase domains. Unlike with inhibitors acting against the active kinase domain, the outcome of pharmacological inhibition/stabilization of the pseudokinase domain in JAKs is not fully understood. A compound binding to TYK2 JH2 was identified in a screen using IL-23-stimulated transcriptional assay [144] and was revealed to be selective in kinome profiling, the only off-targets being JAK1 JH2 and IκB kinase (IKK). Despite binding to JAK1 JH2, the compound does not inhibit JAK1-mediated IL-15 receptor signaling. Further research on TYK2 JH2 binders resulted in a clinical compound, BMS-986165, having a picomolar potency against TYK2 JH2 and efficacy in preclinical mouse models of SLE and IBD [145]. A phase I study with 108 participants found BMS-986165 to be safe and well-tolerated with no serious adverse events [146]. In a recently published phase II study of 267 patients with moderate to severe psoriasis BMS-986165 showed clinical efficacy at a daily dose of 3 mg and higher [147]. Adverse events, most commonly nasopharyngitis, headache, diarrhea, nausea, and upper respiratory tract infection, were more frequent in patients receiving the drug compared with placebo (55–80% for active treatment groups compared with 51% for placebo group), but longer-duration clinical trials with more patients are needed to define the safety and durability of the clinical effects. Currently, the compound is in phase II trials as a monotherapy for SLE and CD, and phase III trials for moderate to severe psoriasis (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT03599622, NCT03624127, NCT03252587, NCT03611751, and NCT02931838).

4 Future Perspectives

Several cytokines play central roles in the pathogenesis of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, and thus therapeutic approaches that target multiple cytokines simultaneously present a viable treatment option. Inhibition of JAKs results in direct suppression of multiple cytokine signaling pathways and affects production of another set of cytokines. For example, inhibition of IL-23 signaling through JAK2/TYK2 suppresses production of IL-17 [51, 52], signaling of which is JAK-independent and cannot be directly controlled with JAK inhibitors. On the other hand, broad cytokine inhibition may lead to unwanted off-target activity and adverse effects. For example, signaling through JAK2 has an important role in erythropoiesis and JAK2 inhibition might therefore promote neutropenia, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. However, this has not been reported for baricitinib (at doses 2–4 mg once daily) in clinical use for RA although baricitinib inhibits JAK1 and JAK2 with equal potency, highlighting the dose dependency of adverse effects [148].

Highly selective JAK inhibition could increase the precision of therapy and could lead to decreased off-target activity and thus increased efficacy and safety. JAK3, for example, has a more defined function than other JAKs, which participate in multiple cellular processes. JAK3 associates only with the common γ-chain receptor, and it is expressed selectively in lymphoid and myeloid cells. Consequently, specific JAK3 inhibition may be beneficial in suppressing inflammatory responses with less interference to off-target cellular functions and therefore reduced adverse effects. Currently, results from clinical trials with the moderately selective JAK3 inhibitors decernotinib and peficitinib are available. These inhibitors demonstrate efficacy and adverse effects comparable to the pan-JAK inhibitor tofacitinib. Data from trials of highly JAK3-selective covalent inhibitor PF-06651600 will, once released, allow the potential of selective JAK3 inhibition in the treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune diseases to be revealed.

Pan-JAK inhibitor tofacitinib is generally well-tolerated at clinically approved doses, and only the increased risk of viral infections (herpes zoster) distinguishes its safety profile from that of biological DMARDs (bDMARDs). Infection-wise, a possible advantage of JAK inhibitors over bDMARDs is the relatively short half-life of JAKinibs: in case of severe infection, the drug can be stopped and the immunosuppressive effect removed. A possible advantage of selective inhibitors over pan-JAK inhibitors arises from the potentially improved safety profile, which could allow the use of higher doses. It is still unknown if patients who do not respond adequately to tofacitinib would obtain therapeutic response of, for example, JAK1-selective inhibitors. Tofacitinib failed to meet its efficacy milestone in patients with CD, although some indications of biological activity were obtained [42]. Moderately JAK1-selective filgotinib, on the other hand, has proven to be efficacious in phase II trials in CD [104]. The therapeutic responses of biologics as well as JAKinibs in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases are difficult to predict based on the current knowledge. Consequently, inhibitors selective for JAK1, JAK3, as well as pan-JAK inhibitors are all undergoing clinical trials against the same set of diseases.

5 Conclusions

Several phase II studies suggest that pan-JAK and moderately selective JAK inhibitors are equally effective in treatment of RA but currently there are not sufficient data for reliable comparison in other immune-mediated diseases. More clinical data, especially for highly selective inhibitors, are required to judge the prospects of selective JAK targeting in inflammatory and autoimmune diseases.

References

Leonard WJ, O’Shea JJ. Jaks and STATs: biological implications. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:293–322.

Lim CP, Cao X. Structure, function, and regulation of STAT proteins. Mol Biosyst. 2006;2:536–50.

Delgoffe GM, Vignali DAA. STAT heterodimers in immunity. Jak-Stat. 2013;2:e23060.

Hammarén HM, Virtanen AT, Raivola J, Silvennoinen O. The regulation of JAKs in cytokine signaling and its breakdown in disease. Cytokine. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2018.03.041 (Epub 2018 May 21).

Ferrao R, Lupardus PJ. The Janus kinase (JAK) FERM and SH2 domains: bringing specificity to JAK-receptor interactions. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2017;8:71.

Luo H, Rose P, Barber D, Hanratty WP, Lee S, Roberts TM, et al. Mutation in the Jak kinase JH2 domain hyperactivates Drosophila and mammalian Jak-Stat pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1562–71.

Saharinen P, Silvennoinen O. The pseudokinase domain is required for suppression of basal activity of Jak2 and Jak3 tyrosine kinases and for cytokine-inducible activation of signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47954–63.

Haan C, Behrmann I, Haan S. Perspectives for the use of structural information and chemical genetics to develop inhibitors of Janus kinases. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:504–27.

Hammarén HM, Virtanen AT, Silvennoinen O. Nucleotide-binding mechanisms in pseudokinases. Biosci Rep. 2016;36:e00282.

Schleinitz N, Vély F, Harle J-R, Vivier E. Natural killer cells in human autoimmune diseases. Immunology. 2010;131:451–8.

Laria A, Mazzocchi D, Scarpellini M. The macrophages in rheumatic diseases. J Inflamm Res. 2016;9:1–11.

Kiefer K, Oropallo M, Cancro M, Marshak-Rothstein A. Role of type I interferons in the activation of autoreactive B cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 2012;90:498–504.

Firestein GS, McInnes IB. Immunopathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Immunity. 2017;46:183–96.

McInnes IB, Schett G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2205–19.

Li P, Zheng Y, Chen X. Drugs for autoimmune inflammatory diseases: From small molecule compounds to anti-TNF biologics. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:1–12.

Thomas S, Fisher KH, Snowden JA, Danson SJ, Brown S, Zeidler MP. Methotrexate is a JAK/STAT pathway inhibitor. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130078.

Isomäki P, Junttila I, Vidqvist KL, Korpela M, Silvennoinen O. The activity of JAK-STAT pathways in rheumatoid arthritis: Constitutive activation of STAT3 correlates with interleukin 6 levels. Rheumatology. 2015;54:1103–13.

van Vollenhoven R, Fleischmann R, Cohen S, Lee E, García Meijide J, Wagner S, et al. Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:508–19.

Fleischmann R, Cutolo M, Genovese M, Lee E, Kanik K, Sadis S, et al. Phase IIb dose-ranging study of the oral JAK inhibitor tofacitinib (CP-690,550) or adalimumab monotherapy versus placebo in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:617–29.

Burmester GR, Blanco R, Charles-Schoeman C, Wollenhaupt J, Zerbini C, Benda B, et al. Tofacitinib (CP-690,550) in combination with methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis with an inadequate response to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013;381:451–60.

Wollenhaupt J, Silverfield J, Lee EB, Curtis JR, Wood SP, Soma K, et al. Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in open-label, longterm extension studies. J Rheumatol. 2014;41:837–52.

Fleischmann R, Wollenhaupt J, Takiya L, Maniccia A, Kwok K, Wang L, et al. Safety and maintenance of response for tofacitinib monotherapy and combination therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: an analysis of pooled data from open-label long-term extension studies. RMD Open. 2017;3:1–13.

Salgado E, Gόmez-reino JJ. The JAK inhibitor tofacitinib for active rheumatoid arthritis: results from phase III trials. Int J Clin Rheumtol. 2013;8:315–26.

Sonomoto K, Yamaoka K, Kubo S, Hirata S, Fukuyo S, Maeshima K, et al. Concise report Effects of tofacitinib on lymphocytes in rheumatoid arthritis : relation to efficacy and infectious adverse events. Rheumatology. 2014;53:914–8.

Taylor PC, Keystone EC, van der Heijde D, Weinblatt ME, del Carmen Morales L, Reyes Gonzaga J, et al. Baricitinib versus placebo or adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:652–62.

European Medicines Agency. Olumiant, INN-baricitinib. Annex I summary of product characteristics. European Public Assessment Report. 2018. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/004085/WC500223723.pdf. Accessed 27 Aug 2018.

Fleischmann R, Schiff M, van der Heijde D, Ramos-Remus C, Spindler A, Stanislav M, et al. Baricitinib, methotrexate, or combination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and no or limited prior disease-modifying antirheumatic drug treatment. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(3):506–17.

Thomas GAO, Rhodes J, Green JT, Richardson C. Role of smoking in inflammatory bowel disease: implications for therapy. Postgrad Med J. 2000;76:273–9.

Nemeth ZH, Bogdanovski DA, Barratt-Stopper P, Paglinco SR, Antonioli L, Rolandelli RH. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis show unique cytokine profiles. Cureus. 2017;9:e1177.

Korolkova OY, Myers JN, Pellom ST, Wang L, M’Koma AE. Characterization of serum cytokine profile in predominantly colonic inflammatory bowel disease to delineate ulcerative and Crohn’s colitides. Clin Med Insights Gastroenterol. 2015;8:29–44.

Narula N, Rubin DT, Sands BE. Novel therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: an evaluation of the evidence. Am J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2016;3:38–44.

Girardin M, Manz M, Manser C, Biedermann L, Wanner R, Frei P, et al. First-line therapies in inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion. 2012;86:6–10.

Neurath MF. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:329–42.

Reinisch W, Hommes D, Van Assche G, Colombel J, Gendre J, Oldenburg B, et al. A dose escalating, placebo controlled, double blind, single dose and multidose, safety and tolerability study of fontolizumab, a humanised anti-interferon γ antibody, in patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2006;55:1138–44.

Musch E, Andus T, Kruis W, Raedler A, Spehlmann M, Schreiber S, et al. Interferon-beta-1a for the treatment of steroid-refractory. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3565:581–6.

Herrlinger KR, Witthoeft T, Raedler A, Bokemeyer B, Krummenerl T, Schulzke JD, et al. Randomized, double blind controlled trial of subcutaneous recombinant human interleukin-11 versus prednisolone in active Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:793–7.

Tilg H, Ulmer H, Kaser A, Weiss G. Role of IL-10 for induction of anemia during inflammation. J Immunol. 2002;169:2204–9.

Ito H, Takazoe M, Fukuda Y, Hibi T, Kusugami K, Andoh A, et al. A pilot randomized trial of a human anti-interleukin-6 receptor monoclonal antibody in active Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:989–96.

Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, Jacobstein D, Lang Y, Friedman JR, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1946–60.

Sandborn WJ, Su C, Sands BE, D’Haens GR, Vermeire S, Schreiber S, et al. Tofacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1723–36.

Panés J, Vermeire S, Lindsay JO, Sands BE, Su C, Friedman G, et al. Tofacitinib in patients with ulcerative colitis: health-related quality of life in phase 3 randomized controlled induction and maintenance studies. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2017;12:145–56.

Sandborn WJ, Ghosh S, Panes J, Vranic I, Wang W. A phase 2 study of tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, in patients with Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1485–93.

Lebwohl MG, Bachelez H, Barker J, Girolomoni G, Kavanaugh A, Langley RG, et al. Patient perspectives in the management of psoriasis: results from the population-based multinational assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:871–81.

Lebwohl MG, Kavanaugh A, Armstrong AW, Van Voorhees AS. US perspectives in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: patient and physician results from the population-based Multinational Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (MAPP) Survey. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2016;17:87–97.

Ogawa E, Sato Y, Minagawa A, Okuyama R. Pathogenesis of psoriasis and development of treatment. J Dermatol. 2018;45:264–72.

Bai F, Zheng W, Dong Y, Wang J, Garstka MA, Li R, et al. Serum levels of adipokines and cytokines in psoriasis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2018;9:1266–78.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psoriasis: assessment and management (Clinical Guideline CG153). 2012. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg153/chapter/1-Guidance#principles-of-care. Accessed 27 Aug 2018.

Cather JC, Young M, Bergman MJ. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2017;10:S16–25.

Papp KA, Blauvelt A, Bukhalo M, Gooderham M, Krueger JG, Lacour J-P, et al. Risankizumab versus ustekinumab for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30:1551–60.

Ritchlin C, Krueger J. New therapies for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2016;28:204–10.

Sofen H, Smith S, Matheson RT, Leonardi CL, Calderon C, Brodmerkel C, et al. Guselkumab (an IL-23-specific mAb) demonstrates clinical and molecular response in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:1032–40.

Krueger JG, Ferris LK, Menter A, Wagner F, White A, Visvanathan S, et al. Anti-IL-23A mAb BI 655066 for treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis: Safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and biomarker results of a single-rising-dose, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(116–124):e7.

Papp KA, Menter MA, Abe M, Elewski B, Feldman SR, Gottlieb AB, et al. Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: results from two randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:949–61.

Papp KA, Krueger JG, Feldman SR, Langley RG, Thaci D, Torii H, et al. Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: long-term efficacy and safety results from 2 randomized phase-III studies and 1 open-label long-term extension study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:841–50.

Bachelez H, Van De Kerkhof PCM, Strohal R, Kubanov A, Valenzuela F, Lee JH, et al. Tofacitinib versus etanercept or placebo in moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis: a phase 3 randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2015;386:552–61.

Papp KA, Menter MA, Raman M, Disch D, Schlichting DE, Gaich C, et al. A randomized phase 2b trial of baricitinib, an oral Janus kinase (JAK) 1/JAK2 inhibitor, in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:1266–76.

Ports WC, Khan S, Lan S, Lamba M, Bolduc C, Bissonnette R, et al. A randomized phase 2a efficacy and safety trial of the topical Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib in the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:137–45.

Punwani N, Burn T, Scherle P, Flores R, Shi J, Collier P, et al. Downmodulation of key inflammatory cell markers with a topical Janus kinase 1/2 inhibitor. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:989–97.

Papp KA, Bissonnette R, Gooderham M, Feldman SR, Iversen L, Soung J, et al. Treatment of plaque psoriasis with an ointment formulation of the Janus kinase inhibitor, tofacitinib: a phase 2b randomized clinical trial. BMC Dermatol. 2016;16:1–12.

Howell MD, Fitzsimons C, Smith PA. JAK/STAT inhibitors and other small molecule cytokine antagonists for the treatment of allergic disease. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120:367–75.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Atopic eczema in under 12s: diagnosis and management (Clinical Guideline CG57). 2007. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG57/chapter/1-Guidance#treatment. Accessed 27 Aug 2018.

Gooderham MJ, Hong HCH, Eshtiaghi P, Papp KA. Dupilumab: a review of its use in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:28–36.

Bissonnette R, Papp KA, Poulin Y, Gooderham M, Raman M, Mallbris L, et al. Topical tofacitinib for atopic dermatitis: a phase IIa randomized trial. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:902–11.

Levy LL, Urban J, King BA. Treatment of recalcitrant atopic dermatitis with the oral Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib citrate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73:395–9.

Guttman-Yassky E, Silverberg JI, Nemoto O, Forman SB, Wilke A, Prescilla R, et al. Baricitinib in adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 2 parallel, double-blinded, randomized placebo-controlled multiple-dose study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2018.01.018 (Epub 2018 Feb 1).

Ranganathan V, Gracey E, Brown MA, Inman RD, Haroon N. Pathogenesis of ankylosing spondylitis-recent advances and future directions. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13:359–67.

Gracey E, Yao Y, Green B, Qaiyum Z, Baglaenko Y, Lin A, et al. Sexual dimorphism in the Th17 signature of ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:679–89.

Davidson SI, Liu Y, Danoy PA, Wu X, Thomas GP, Jiang L, et al. Association of STAT3 and TNFRSF1A with ankylosing spondylitis in Han Chinese. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:289–92.

Cortes A, Hadler J, Pointon JP, Robinson PC, Karaderi T, Leo P, et al. Identification of multiple risk variants for ankylosing spondylitis through high-density genotyping of immune-related loci. Nat Genet. 2013;45:730–8.

Evans DM, Spencer CCA, Pointon JJ, Su Z, Harvey D, Kochan G, et al. Interaction between ERAP1 and HLA-B27 in ankylosing spondylitis implicates peptide handling in the mechanism for HLA-B27 in disease susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2013;43:761–7.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Spondyloarthritis in over 16s: diagnosis and management (NICE guideline NG65). 2017. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng65. Accessed 27 Aug 2018.

Baeten D, Østergaard M, Wei JCC, Sieper J, Järvinen P, Tam LS, et al. Risankizumab, an IL-23 inhibitor, for ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept, dose-finding phase 2 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:1295–302.

Van Der Heijde D, Deodhar A, Wei JC, Drescher E, Fleishaker D, Hendrikx T, et al. Tofacitinib in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a phase II, 16-week, randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1340–7.

Guimarães PM, Scavuzzi BM, Stadtlober NP, Franchi Santos LFDR, Lozovoy MAB, Iriyoda TMV, et al. Cytokines in systemic lupus erythematosus: Far beyond Th1/Th2 dualism lupus: cytokine profiles. Immunol Cell Biol. 2017;95:824–31.

Castro SG, Isenberg DA. Belimumab in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): evidence-to-date and clinical usefulness. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2017;9:75–85.

Riggs JM, Hanna RN, Rajan B, Zerrouki K, Karnell JL, Sagar D, et al. Characterisation of anifrolumab, a fully human anti-interferon receptor antagonist antibody for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus Sci Med. 2018;5:e000261.

Suárez-Fariñas M, Ungar B, Noda S, Shroff A, Mansouri Y, Fuentes-Duculan J, et al. Alopecia areata profiling shows TH1, TH2, and IL-23 cytokine activation without parallel TH17/TH22 skewing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:1277–87.

Loh SH, Moon HN, Lew BL, Sim WY. Role of T helper 17 cells and T regulatory cells in alopecia areata: comparison of lesion and serum cytokine between controls and patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1028–33.

Mackay-Wiggan J, Jabbari A, Nguyen N, Cerise JE, Clark C, Ulerio G, et al. Oral ruxolitinib induces hair regrowth in patients with moderate-to-severe alopecia areata. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e89790.

Wallace DJ, Furie RA, Tanaka Y, Kalunian KC, Mosca M, Petri MA, et al. Baricitinib for systemic lupus erythematosus: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018;392:222–31.

Yamaoka K. Janus kinase inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2016;32:29–33.

Kremer JM, Bloom BJ, Breedveld FC, Coombs JH, Fletcher MP, Gruben D, et al. The safety and efficacy of a JAK inhibitor in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled phase IIa trial of three dosage levels of CP-690,550 versus placebo. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1895–905.

Strand V, Ahadieh S, French J, Geier J, Krishnaswami S, Menon S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of serious infections with tofacitinib and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug treatment in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:362.

Charles-Schoeman C, Wicker P, Gonzalez-Gay MA, Boy M, Zuckerman A, Soma K, et al. Cardiovascular safety findings in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46:261–71.

Scott IC, Hider SL, Scott DL. Thromboembolism with Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors for rheumatoid arthritis: how real is the risk? Drug Saf. 2018;41:645–53.

Xie F, Yun H, Bernatsky S, Curtis JR. Risk of gastrointestinal perforation among rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving tofacitinib, tocilizumab, or other biologic treatments. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:2612–7.

Bengtsson K, Forsblad-d’Elia H, Lie E, Klingberg E, Dehlin M, Exarchou S, et al. Are ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis and undifferentiated spondyloarthritis associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events? A prospective nationwide population-based cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19:102.

Eriksson JK, Jacobsson L, Bengtsson K, Askling J. Is ankylosing spondylitis a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, and how do these risks compare with those in rheumatoid arthritis? Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:364–70.

Smyth LA, Collins I. Measuring and interpreting the selectivity of protein kinase inhibitors. J Chem Biol. 2009;2:131–51.

Knight ZA, Shokat KM. Features of selective kinase inhibitors. Chem Biol. 2005;12:621–37.

Sohn SJ, Barrett K, Van Abbema A, Chang C, Kohli PB, Kanda H, et al. A restricted role for TYK2 catalytic activity in human cytokine responses revealed by novel TYK2-selective inhibitors. J Immunol. 2013;191:2205–16.

Yu V, Pistillo J, Archibeque I, Han Lee J, Sun B-C, Schenkel LB, et al. Differential selectivity of JAK2 inhibitors in enzymatic and cellular settings. Exp Hematol. 2013;41:491–500.

Rodig SJ, Meraz MA, White JM, Lampe PA, Riley JK, Arthur CD, et al. Disruption of the Jak1 gene demonstrates obligatory and nonredundant roles of the Jaks in cytokine-induced biologic responses. Cell. 1998;93:373–83.

Albacker LA, Wu J, Smith P, Warmuth M, Stephens PJ, Zhu P, et al. Loss of function JAK1 mutations occur at high frequency in cancers with microsatellite instability and are suggestive of immune evasion. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176181.

Flex E, Petrangeli V, Stella L, Chiaretti S, Hornakova T, Knoops L, et al. Somatically acquired JAK1 mutations in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Exp Med. 2008;205:751–8.

Jeong EG, Kim MS, Nam HK, Min CK, Lee S, Chung YJ, et al. Somatic mutations of JAK1 and JAK3 in acute leukemias and solid cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3716–21.

Ren Y, Zhang Y, Liu RZ, Fenstermacher DA, Wright KL, Teer JK, et al. JAK1 truncating mutations in gynecologic cancer define new role of cancer-associated protein tyrosine kinase aberrations. Sci Rep. 2013;3:3042.

Haan C, Rolvering C, Raulf F, Kapp M, Drückes P, Thoma G, et al. Jak1 has a dominant role over Jak3 in signal transduction through γc-containing cytokine receptors. Chem Biol. 2011;18:314–23.

Shimoda K, Kato K, Aoki K, Matsuda T, Miyamoto A, Shibamori M, et al. Tyk2 plays a restricted role in IFN alpha signaling, although it is required for IL-12-mediated T cell function. Immunity. 2000;13:561–71.

Menet CJ, Fletcher SR, Van Lommen G, Geney R, Blanc J, Smits K, et al. Triazolopyridines as selective JAK1 inhibitors: from hit identification to GLPG0634. J Med Chem. 2014;57:9323–42.

Namour F, Galien R, Gheyle L, Vanhoutte F, Vayssière B, van der Aa A, et al. Once-daily high dose regimens of GLPG0634 in healthy volunteers are safe and provide continuous inhibition of JAK1 but not JAK2 [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(Suppl):S573.

Westhovens R, Taylor PC, Alten R, Pavlova D, Enriquez-Sosa F, Mazur M, et al. Filgotinib (GLPG0634/GS-6034), an oral JAK1 selective inhibitor, is effective in combination with methotrexate (MTX) in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and insufficient response to MTX: results from a randomised, dose-finding study (DARWIN 1). Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:998–1008.

Kavanaugh A, Kremer J, Ponce L, Cseuz R, Reshetko OV, Stanislavchuk M, et al. Filgotinib (GLPG0634/GS-6034), an oral selective JAK1 inhibitor, is effective as monotherapy in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results from a randomised, dose-finding study (DARWIN 2). Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1009–19.

Vermeire S, Schreiber S, Petryka R, Kuehbacher T, Hebuterne X, Roblin X, et al. Clinical remission in patients with moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease treated with filgotinib (the FITZROY study): results from a phase 2, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:266–75.

Mease P, Coates LC, Helliwell PS, Stanislavchuk M, Rychlewska-Hanczewska A, Dudek A, et al. Efficacy and safety of filgotinib, a selective Janus kinase 1 inhibitor, in patients with active psoriatic arthritis (EQUATOR): results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018;392:2367–77.

van der Heijde D, Baraliakos X, Gensler LS, Maksymowych WP, Tseluyko V, Nadashkevich O, et al. Efficacy and safety of filgotinib, a selective Janus kinase 1 inhibitor, in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (TORTUGA): results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2018;392:2378–87.

Genovese MC, Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME, Burmester GR, Meerwein S, Camp HS, et al. Efficacy and safety of ABT-494, a selective JAK-1 inhibitor, in a phase IIb study in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:2857–66.

Kremer JM, Emery P, Camp HS, Friedman A, Wang L, Othman AA, et al. A phase IIb study of ABT-494, a selective JAK-1 inhibitor, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:2867–77.

Burmester GR, Kremer JM, Van den Bosch F, Kivitz A, Bessette L, Li Y, et al. Safety and efficacy of upadacitinib in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and inadequate response to conventional synthetic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (SELECT-NEXT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2018;391:2503–12.

Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Panes J, D’Haens GR, Colombel JF, Zhou Q, et al. Safety and efficacy of ABT-494 (upadacitinib), an oral Jak1 inhibitor, as induction therapy in patients with Crohn’s disease: results from Celest. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:S1308–9.

Bissonnette R, Luchi M, Fidelus-Gort R, Jackson S, Zhang H, Flores R, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation study of the safety and efficacy of INCB039110, an oral janus kinase 1 inhibitor, in patients with stable, chronic plaque psoriasis. J Dermatol Treat. 2016;27:332–8.

Kettle JG, Åstrand A, Catley M, Grimster NP, Nilsson M, Su Q, et al. Inhibitors of JAK-family kinases: an update on the patent literature 2013-2015, part 1. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2017;27:127–43.

Luchi M, Fidelus-Gort R, Douglas D, Zhang H, Flores R, Newton R, et al. A randomized, dose-ranging, placebo-controlled, 84-day study of INCB039110, a selective Janus kinase-1 inhibitor, in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1797.

Ludbrook VJ, Hicks KJ, Hanrott KE, Patel JS, Binks MH, Wyres MR, et al. Investigation of selective JAK1 inhibitor GSK2586184 for the treatment of psoriasis in a randomized placebo-controlled phase IIa study. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174:985–95.

Kahl L, Patel J, Layton M, Binks M, Hicks K, Leon G, et al. Safety, tolerability, efficacy and pharmacodynamics of the selective JAK1 inhibitor GSK2586184 in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2016;25:1420–30.

Vazquez ML, Kaila N, Strohbach JW, Trzupek JD, Brown MF, Flanagan ME, et al. Identification of N-{cis-3-[methyl(7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-yl)amino]cyclobutyl}propane-1-sulfo namide (PF-04965842): a selective JAK1 clinical candidate for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. J Med Chem. 2018;61:1130–52.

Schmieder GJ, Draelos ZD, Pariser DM, Banfield C, Cox L, Hodge M, et al. Efficacy and safety of the Janus kinase 1 inhibitor PF-04965842 in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:54–62.

Kawamura M, McVicar DW, Johnston JA, Blake TB, Chen YQ, Lal BK, et al. Molecular cloning of L-JAK, a Janus family protein-tyrosine kinase expressed in natural killer cells and activated leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6374–8.

Musso T, Johnston JA, Linnekin D, Varesio L, Rowe TK, O’Shea JJ, et al. Regulation of JAK3 expression in human monocytes: phosphorylation in response to interleukins 2, 4, and 7. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1425–31.

Tortolani PJ, Lal BK, Riva A, Johnston JA, Chen YQ, Reaman GH, et al. Regulation of JAK3 expression and activation in human B cells and B cell malignancies. J Immunol. 1995;155:5220–6.

O’Shea JJ, Husa M, Li D, Hofmann SR, Watford W, Roberts JL, et al. Jak3 and the pathogenesis of severe combined immunodeficiency. Mol Immunol. 2004;41:727–37.

Degryse S, De Bock CE, Cox L, Demeyer S, Gielen O, Mentens N, et al. JAK3 mutants transform hematopoietic cells through JAK1 activation, causing T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a mouse model. Blood. 2014;124:3092–100.

Walters DK, Mercher T, Gu T-L, O’Hare T, Tyner JW, Loriaux M, et al. Activating alleles of JAK3 in acute megakaryoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:65–75.

Bouchekioua A, Scourzic L, de Wever O, Zhang Y, Cervera P, Aline-Fardin A, et al. JAK3 deregulation by activating mutations confers invasive growth advantage in extranodal nasal-type natural killer cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2014;28:338–48.

Farmer LJ, Ledeboer MW, Hoock T, Arnost MJ, Bethiel RS, Bennani YL, et al. Discovery of VX-509 (decernotinib): a potent and selective Janus kinase 3 inhibitor for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. J Med Chem. 2015;58:7195–216.

Mahajan S, Hogan JK, Shlyakhter D, Oh L, Salituro FG, Farmer L, et al. VX-509 (decernotinib) is a potent and selective janus kinase 3 inhibitor that attenuates inflammation in animal models of autoimmune disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;353:405–14.

Genovese MC, van Vollenhoven RF, Pacheco-Tena C, Zhang Y, Kinnman N. VX-509 (decernotinib), an oral selective JAK-3 inhibitor, in combination with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:46–55.

Genovese MC, Yang F, Ostergaard M, Kinnman N. Efficacy of VX-509 (decernotinib) in combination with a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: clinical and MRI findings. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1979–83.

Gadina M, Schwartz DM, O’Shea JJ. Decernotinib: a next-generation jakinib. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:31–4.

Huang J, Chavan A, Viswanathan L, Luo X, Garg V, Zhang Y, et al. THU0135 evaluation of drug-drug interactions of VX-509 (decernotinib), an oral selective Janus kinase 3 inhibitor, in healthy human volunteers [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:225–6.

Papp K, Pariser D, Catlin M, Wierz G, Ball G, Akinlade B, et al. A phase 2a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, sequential dose-escalation study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of ASP015K, a novel Janus kinase inhibitor, in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:767–76.

Takeuchi T, Tanaka Y, Iwasaki M, Ishikura H, Saeki S, Kaneko Y. Efficacy and safety of the oral Janus kinase inhibitor peficitinib (ASP015K) monotherapy in patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis in Japan: a 12-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase IIb study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1057–64.

Kivitz AJ, Gutierrez-Urena SR, Poiley J, Genovese MC, Kristy R, Shay K, et al. Peficitinib, a JAK Inhibitor, in the treatment of moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to methotrexate. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:709–19.

Genovese MC, Greenwald M, Codding C, Zubrzycka-Sienkiewicz A, Kivitz AJ, Wang A, et al. Peficitinib, a JAK inhibitor, in combination with limited conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in the treatment of moderate-to-severe rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:932–42.

Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Zhang H, Strauss R, et al. Peficitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, in moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis: results from a randomized, phase 2 study. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:1158–69.

Thorarensen A, Dowty ME, Banker ME, Juba B, Jussif J, Lin T, et al. Design of a Janus kinase 3 (JAK3) specific inhibitor 1-((2S,5R)-5-((7H-pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidin-4-yl)amino)-2-methylpiperidin-1-yl)prop-2-en-1-one (PF-06651600) allowing for the interrogation of JAK3 signaling in humans. J Med Chem. 2017;60:1971–93.

Telliez J-B, Dowty ME, Wang L, Jussif J, Lin T, Li L, et al. Discovery of a JAK3-selective inhibitor: functional differentiation of JAK3-selective inhibition over pan-JAK or JAK1-selective inhibition. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:3442–51.

Seto Y, Nakajima H, Suto A, Shimoda K, Saito Y, Nakayama KI, et al. Enhanced Th2 cell-mediated allergic inflammation in Tyk2-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2003;170:1077–83.

Minegishi Y, Saito M, Morio T, Watanabe K, Agematsu K, Tsuchiya S, et al. Human tyrosine kinase 2 deficiency reveals its requisite roles in multiple cytokine signals involved in innate and acquired immunity. Immunity. 2006;25:745–55.