Abstract

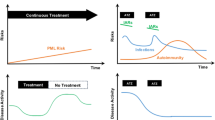

Alemtuzumab is a humanized anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody. Treatment in humans results in a rapid, profound, and prolonged B- and T-cell lymphopenia. Subsequently, lymphocyte reconstitution by homeostatic mechanisms alters the composition, phenotype, and function of T-cell subsets, thus allowing the immune system to be ‘reset’. One phase II and two phase III randomized, multicenter, single-blinded (outcomes assessor) clinical trials of alemtuzumab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis have now been completed. Against an active comparator and the current first-line therapy for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (interferon-beta), alemtuzumab showed a significant reduction in annualized relapse rate as well as a significant reduction in the accumulation of disability. These outcomes are sustained over at least 5 years following treatment. The most common adverse effects are mild infusion reactions, an increased incidence of mild-to-moderate severity infections and secondary autoimmunity. The latter is observed in a third of treated patients, commonly thyroid disease but other target cells have been described including cytopenias. Marketing authorization applications have been submitted for the use of alemtuzumab in multiple sclerosis to the Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, with licensing expected in 2013. Here, we discuss the outlook for alemtuzumab in multiple sclerosis in light of the currently available therapies, outcomes of and lessons learnt from clinical trials, and the overall position of monoclonal antibodies in modern treatment strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organisation and Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. Atlas—multiple sclerosis resources in the world. Geneva: WHO Press; 2008.

International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium, et al. Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature. 2011;476(7359):214–9.

Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372(9648):1502–17.

Jones JL, et al. Improvement in disability after alemtuzumab treatment of multiple sclerosis is associated with neuroprotective autoimmunity. Brain. 2010;133(8):2232–47.

Trapp BD, et al. Axonal transection in the lesions of multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(5):278–85.

Milligan NM, Newcombe R, Compston DA. A double-blind controlled trial of high dose methylprednisolone in patients with multiple sclerosis: 1 clinical effects. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50(5):511–6.

Sellebjerg F, et al. Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of oral, high-dose methylprednisolone in attacks of MS. Neurology. 1998;51(2):529–34.

Duquette P, et al. Interferon beta-1b is effective in relapsing-remitting multiple-sclerosis—clinical-results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 1993;43(4):655–61.

The IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group, The University of British Columbia MS/MRI Analysis Group. Interferon beta-1b in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: final outcome of the randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 1995;45(7):1277–85.

Jacobs LD, et al. Intramuscular interferon beta-1a for disease progression in relapsing multiple sclerosis. The Multiple Sclerosis Collaborative Research Group (MSCRG). Ann Neurol. 1996;39(3):285–94.

PRISMS (Prevention of Relapses and Disability by Interferon beta-1a Subcutaneously in Multiple Sclerosis) Study Group. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study of interferon beta-1a in relapsing/remitting multiple sclerosis. The Lancet. 1998;352(9139):1498–504.

Shirani A, et al. Association between use of interferon beta and progression of disability in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. JAMA. 2012;308(3):247–56.

Bornstein MB, et al. A pilot trial of Cop 1 in exacerbating-remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(7):408–14.

Johnson KP, et al. Copolymer 1 reduces relapse rate and improves disability in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results of a phase III multicenter, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. The Copolymer 1 Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Neurology. 1995;45(7):1268–76.

Mikol DD, et al. Comparison of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a with glatiramer acetate in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis [the REbif vs Glatiramer Acetate in Relapsing MS Disease (REGARD) study]: a multicentre, randomised, parallel, open-label trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(10):903–14.

Cadavid D, et al. Efficacy of treatment of MS with IFN beta-1b or glatiramer acetate by monthly brain MRI in the BECOME study. Neurology. 2009;72(23):1976–83.

Schwab SR, et al. Lymphocyte sequestration through S1P lyase inhibition and disruption of S1P gradients. Science. 2005;309(5741):1735–9.

Kappos L, et al. Oral fingolimod (FTY720) for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(11):1124–40.

Choi JW, et al. FTY720 (fingolimod) efficacy in an animal model of multiple sclerosis requires astrocyte sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P1) modulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(2):751–6.

Kappos L, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(5):387–401.

Cohen JA, et al. Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(5):402–15.

Rudick RA, et al. Natalizumab plus interferon beta-1a for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(9):911–23.

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33(11):1444–52.

Yousry TA, et al. Evaluation of patients treated with natalizumab for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(9):924–33.

Clifford DB, et al. Natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with multiple sclerosis: lessons from 28 cases. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(4):438–46.

Bloomgren G, et al. Risk of natalizumab-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(20):1870–80.

Calabresi PA, et al. The incidence and significance of anti-natalizumab antibodies: results from AFFIRM and SENTINEL. Neurology. 2007;69(14):1391–403.

Abbott. Annual report (online). http://www.abbott.com/static/content/microsite/annual_report/2010/docs/Abbott_AR2010_Financials.pdf (2010).

Chirino AJ, Ary ML, Marshall SA. Minimizing the immunogenicity of protein therapeutics. Drug Discov Today. 2004;9(2):82–90.

Bartelds GM, et al. Clinical response to adalimumab: relationship to anti-adalimumab antibodies and serum adalimumab concentrations in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(7):921–6.

Baert F, et al. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(7):601–8.

De Groot AS, Scott DW. Immunogenicity of protein therapeutics. Trends Immunol. 2007;28(11):482–90.

Nelson AL, Dhimolea E, Reichert JM. Development trends for human monoclonal antibody therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9(10):767–74.

Hale G, et al. Removal of T cells from bone marrow for transplantation: a monoclonal antilymphocyte antibody that fixes human complement. Blood. 1983;62(4):873–82.

Riechmann L, et al. Reshaping human antibodies for therapy. Nature. 1988;332(6162):323–7.

Rao SP, et al. Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells exhibit heterogeneous CD52 expression levels and show differential sensitivity to alemtuzumab mediated cytolysis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6):e39416.

Rowan WC, et al. Cross-linking of the CAMPATH-1 antigen (CD52) triggers activation of normal human T lymphocytes. Int Immunol. 1995;7(1):69–77.

Watanabe T, et al. CD52 is a novel costimulatory molecule for induction of CD4(+) regulatory T cells. Clin Immunol. 2006;120(3):247–59.

Hale G, et al. Remission induction in non-Hodgkin lymphoma with reshaped human monoclonal antibody CAMPATH-1H. Lancet. 1988;2(8625):1394–9.

Keating MJ, et al. Therapeutic role of alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) in patients who have failed fludarabine: results of a large international study. Blood. 2002;99(10):3554–61.

Barth RN, et al. Outcomes at 3 years of a prospective pilot study of Campath-1H and sirolimus immunosuppression for renal transplantation. Transpl Int. 2006;19(11):885–92.

Maloney DG, et al. Non-myeloablative transplantation. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2002;2002(1):392–421.

Lockwood CM, et al. Treatment of refractory Wegener’s granulomatosis with humanized monoclonal antibodies. QJM. 1996;89(12):903–12.

Moreau T, et al. Preliminary evidence from magnetic resonance imaging for reduction in disease activity after lymphocyte depletion in multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1994;344(8918):298–301.

Coles AJ, et al. Monoclonal antibody treatment exposes three mechanisms underlying the clinical course of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1999;46(3):296–304.

Coles AJ, et al. The window of therapeutic opportunity in multiple sclerosis: evidence from monoclonal antibody therapy. J Neurol. 2006;253(1):98–108.

Camms Trial Investigators. Alemtuzumab vs. interferon beta-1a in early multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(17):1786–801.

Coles AJ, et al. Alemtuzumab more effective than interferon beta-1a at 5-year follow-up of CAMMS223 Clinical Trial. Neurology. 2012;78(14):1069–78.

Cohen JA, et al. Alemtuzumab versus interferon beta 1a as first-line treatment for patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2012;380(9856):1819–28.

Genzyme, Alemtuzumab (Lemtrada™*) significantly reduces relapses in multiple sclerosis vs interferon beta-1a in a phase III study, 2011: http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/10/22/idUS29431+22-Oct-2011+BW20111022.

Coles, AJ, et al, Alemtuzumab for patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis after disease-modifying therapy: a randomised controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9856):1829–39.

Genzyme, Significant improvement in disability scores observed in multiple sclerosis patients who received Lemtrada™* (alemtuzumab) compared with rebif® in phase III trial, 2012. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/04/24/idUS217878+24-Apr-2012+BW20120424.

Mould DR, et al. Population pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics of alemtuzumab (Campath) in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and its link to treatment response. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64(3):278–91.

Cox AL, et al. Lymphocyte homeostasis following therapeutic lymphocyte depletion in multiple sclerosis. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35(11):3332–42.

Thompson SA, et al. B-cell reconstitution and BAFF after alemtuzumab (Campath-1H) treatment of multiple sclerosis. J Clin Immunol. 2010;30(1):99–105.

Coles AJ, et al. Pulsed monoclonal antibody treatment and autoimmune thyroid disease in multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 1999;354(9191):1691–5.

Gilquin J, et al. Delayed occurrence of Graves’ disease after immune restoration with HAART. Highly active antiretroviral therapy. Lancet. 1998;352(9144):1907–8.

Jones JL, et al. IL-21 drives secondary autoimmunity in patients with multiple sclerosis, following therapeutic lymphocyte depletion with alemtuzumab (Campath-1H). J Clin Invest. 2009;119(7):2052–61.

Moreau T, et al. Transient increase in symptoms associated with cytokine release in patients with multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1996;119 (Pt 1)(1):225–37.

Kraimps JL, et al. Multicentre study of thyroid nodules in patients with Graves’ disease. Br J Surg. 2000;87(8):1111–3.

Kim WB, et al. Ultrasonographic screening for detection of thyroid cancer in patients with Graves’ disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2004;60(6):719–25.

Berker D, et al. Prevalence of incidental thyroid cancer and its ultrasonographic features in subcentimeter thyroid nodules of patients with hyperthyroidism. Endocrine. 2011;39(1):13–20.

Somerfield J, et al. A novel strategy to reduce the immunogenicity of biological therapies. J Immunol. 2010;185(1):763–8.

McCarthy C, et al. Immune Responses to Vaccination in Multiple Sclerosis Patients Post-alemtuzumab Treatment (CAM-VAC study (poster). In: 5th Joint triennial congress of the European and Americas Committees for treatment and research in multiple sclerosis. Amsterdam: The Netherlands; 2011.

Discontinuation of licensed supplies of alemtuzumab (Mabcampath). 8 Aug 2012: National electronic Library for Medicines.

Acknowledgments

Thomas Williams and Laura Azzopardi have no conflicts of interest to declare. Alasdair Coles has received honoraria for speaking at satellite symposia on behalf of Genzyme; for consultancy from Genzyme and Merck-Serono; and his department has received grant support from Genzyme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, T., Coles, A. & Azzopardi, L. The Outlook for Alemtuzumab in Multiple Sclerosis. BioDrugs 27, 181–189 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-013-0028-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-013-0028-3