Abstract

Background

Deaf people experience health inequalities compared to hearing populations. The EQ-5D, a widely used, standardised, generic measure of health status, which is available in over 100 languages, was recently translated into British Sign Language (BSL) and initial validation conducted. Using data from this previous study of the EQ-5D-5L BSL we aimed to assess (1) whether responses to the EQ-5D differed between a sample of Deaf BSL users and the general population (2) whether socio-demographic characteristics and clinical measures were associated with EQ-5D index scores in Deaf BSL users and (3) the impact of psychological distress and depression on health status in Deaf BSL users.

Methods

Published population tariffs were applied to the EQ-5D-5L BSL, using the crosswalk methodology, to estimate health state values. Descriptive statistics (mean, SD, 95% CIs) compared Deaf BSL signer participants’ (n = 92) responses to data from the general population. Descriptive statistics and linear regression analyses were used to identify associations between Deaf participants’ EQ-5D index scores, socio-demographic characteristics, physical health and depression. Descriptive statistics compared the BSL index scores for people with psychological distress/depression to those from two cross-sectional, population-based surveys.

Results

Using the EQ-5D, Deaf participants had lower mean health-state values (0.78; 95% CI 0.72–0.83; n = 89) than people participating in the 2017 Health Survey for England (0.84; 95% CI 0.83–0.84; n = 7169). Unlike larger studies, such as the Health Survey for England sample, there was insufficient evidence to assess whether Deaf participants’ EQ-5D health state values were associated with their demographic characteristics. Nevertheless, analysis of the BSL study data indicated long-standing physical illness was associated with lower health-state values (ordinary least squares coefficient = − 0.354; 95% CI − 0.484, − 0.224; p < 0.01; n = 82). Forty-three percent of our Deaf participants had depression. Participants with depression had reduced health status (0.67; 95% CI 0.58–0.77; n = 36) compared to those with no psychological distress or depression (0.87; 95% CI 0.61–0.67; n = 36).

Conclusions

The study highlights reduced health in the Deaf signing population, compared to the general population. Public health initiatives focused on BSL users, aiming to increase physical and mental health, are needed to address this gap.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

British Deaf Association. Help and resources—British Deaf Association. 2018. https://bda.org.uk/help-resources/. Accessed 24 Aug 2018.

Young A, Hunt R. Research with d/Deaf People. 2011. http://www.lse.ac.uk/LSEHealthAndSocialCare/pdf/SSCRMethodsReview_9_web.pdf. Accessed 07 Aug 2018.

Smith A. Written Ministerial Statement on British Sign Language. House of Commons Hansard Written Ministerial Statements for 18 Mar 2003 (pt 2). 2003. https://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200203/cmhansrd/vo030318/wmstext/30318m02.htm. Accessed 17 Aug 2018.

The Scottish Parliament. British Sign Language (Scotland) Bill. 2014. http://www.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/Bills/82853.aspx. Accessed 17 Aug 2018.

Emond A, Ridd M, Sutherland H, Allsop L, Alexander A, Kyle J. Access to primary care affects the health of Deaf people. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65(631):95–6. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp15X683629.

Barnett S, McKee M, Smith SR, Pearson TA. Deaf sign language users, health inequities, and public health: opportunity for social justice. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A45.

Levine J. Primary care for deaf people with mental health problems. Br J Nurs. 2014;23:459–63. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2014.23.9.459.

Kvam MH, Loeb M, Tambs K. Mental health in deaf adults: symptoms of anxiety and depression among hearing and deaf individuals. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2007;12:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enl015.

Pollard RQ, Barnett S. Health-related vocabulary knowledge among deaf adults. Rehabil Psychol. 2009;54:182–5. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015771.

Alexander A, Ladd P, Powell S, Pearson T, Macdonald J, Pullen G. Deafness might damage your health. Lancet. 2012;379:979–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61670-X.

Barnett SL, Matthews KA, Sutter EJ, DeWindt LA, Pransky JA, O’Hearn AM, David TM, Pollard RQ, Samar VJ, Pearson TA. Collaboration with deaf communities to conduct accessible health surveillance. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52:S250–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.10.011.

Emond A, Ridd M, Sutherland H, Allsop L, Alexander A, Kyle J. The current health of the signing Deaf community in the UK compared with the general population: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e006668. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006668.

van Eldik T, Van der Ende J, Koot HM, Tak JA. Mental health problems of Dutch youth with hearing loss as shown on the youth self report. Am Ann Deaf. 2005;150:11–6. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2005.0024.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Depression in adults: recognition and management. Appendix 15 economic revie. 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90. Accessed 10 Feb 2016.

Szende A, Janssen MB, Cabasés JM, Ramos Goñi JM. Self-reported population health: an international perspective based on EQ-5D. Netherlands, Dordrecht: Springer; 2014.

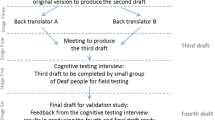

Rogers KD, Pilling M, Davies L, Belk R, Nassimi-Green C, Young A. Translation, validity and reliability of the British Sign Language (BSL) version of the EQ-5D-5L. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:1825–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1235-4.

Barkham M, Bewick B, Mullin T, Gilbody S, Connell J, Cahill J, Mellor-Clark J, Richards D, Unsworth G, Evans C. The CORE-10: a short measure of psychological distress for routine use in the psychological therapies. Couns Psychother Res. 2013;13:3–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2012.729069.

Young A, Rogers K, Davies L, Pilling M, Lovell K, Pilling S, Belk R, Shields G, Dodds C, Campbell M, Nassimi-Green C, Buck D, Oram R. Evaluating the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of British Sign Language Improving Access to Psychological Therapies: an exploratory study. NIHR J Libr. 2017.

University College London, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, National Centre for Social Research (NatCen). Health Survey for England, 2017. [data collection]. UK Data Service. SN: 8488. 2019. https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-8488-1. Accessed 6 Nov 2019.

NHS Digital (2018) Health Survey for England 2017—Methods

UK Data Service Health Survey for England. https://beta.ukdataservice.ac.uk/datacatalogue/series/series?id=2000021. Accessed 13 Nov 2019.

NHS Digital. Health Survey for England 2016 Field documents and measurement protocols. 2016.

van Hout B, Janssen MF, Feng Y-S, Kohlmann T, Busschbach J, Golicki D, Lloyd A, Scalone L, Kind P, Pickard AS. Interim Scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value Health. 2012;15:708–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2012.02.008.

EuroQoL. NICE position statement on the EQ-5D-5L. 2017. https://euroqol.org/nice-position-statement-on-the-eq-5d-5l/. Accessed 20 Aug 2018.

EuroQol NICE position statement on the EQ-5D-5L – EQ-5D. https://euroqol.org/nice-position-statement-on-the-eq-5d-5l/. Accessed 6 Nov 2019.

Mavranezouli I, Brazier JE, Young TA, Barkham M (2011) Using Rasch analysis to form plausible health states amenable to valuation: the development of CORE-6D from a measure of common mental health problems (CORE-OM). Qual Life Res 20:321–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9768-4.

Mihalopoulos C, Chen G, Iezzi A, Khan MA, Richardson J. Assessing outcomes for cost-utility analysis in depression: comparison of five multi-attribute utility instruments with two depression-specific outcome measures. Br J Psychiatry. 2014;205:390–7. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.113.136036.

Office of National Statistics. measuring national well-being: domains and measures. 2018. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/datasets/measuringnationalwellbeingdomainsandmeasures. Accessed 3 Aug 2018.

Belk RA, Pilling M, Rogers KD, Lovell K, Young A. The theoretical and practical determination of clinical cut-offs for the British Sign Language versions of PHQ-9 and GAD-7. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:372. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-1078-0.

Maier W, Falkai P. The epidemiology of comorbidity between depression, anxiety disorders and somatic diseases. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;14Suppl 2:S1–6.

Tyrer P. The case for cothymia: mixed anxiety and depression as a single diagnosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:191–3. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.179.3.191.

Pini S, Cassano GB, Simonini E, Savino M, Russo A, Montgomery SA. Prevalence of anxiety disorders comorbidity in bipolar depression, unipolar depression and dysthymia. J Affect Disord. 1997;42:145–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0327(96)01405-x.

Ballenger JC. Anxiety and Depression: Optimizing Treatments. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;2:71–9. https://doi.org/10.4088/pcc.v02n0301.

Bailey H, Kind P. Preliminary findings of an investigation into the relationship between national culture and EQ-5D value sets. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:1145–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9678-5.

Rogers KD, Ferguson-Coleman E, Young A. Challenges of realising patient-centred outcomes for deaf patients. Patient. 2018;11:9–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-017-0260-x.

Young A, Temple B. Approaches to social research: the case of deaf studies. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014.

Young A, Oram R, Dodds C, Nassimi-Green C, Belk R, Rogers K, Davies L, Lovell K. A qualitative exploration of trial-related terminology in a study involving Deaf British Sign Language users. Trials. 2016;17:219. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1349-6.

Frayne SM, Burns RB, Hardt EJ, Rosen AK, Moskowitz MA. The exclusion of non-English-speaking persons from research. J Gen Intern Med. 1996;11:39–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02603484.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GES, KDR, LMD and AY planned the study; GES, LMD and KDR analysed the data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data; GES and SD conducted literature searching; GES and LMD drafted the first version of the manuscript and all authors contributed to subsequent versions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services Research and Delivery Programme, Grant Award Number: 12/136/79. This report/article presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Conflict of interest

AY declares funding from the National Deaf Children’s Society, as well as current and previous funding from the AHRC, MRC, GCRF, NIHR and NHS England within the last 3 years, related to research in the Deaf population. LMD declares funding from the MRC, ESRC, NIHR, Department of Health and Cancer Research UK, some of which relates to research in the Deaf population. KR declares current funding from the NIHR and National Deaf Children’s Society, as well as funding from the AHRC, Department for Education and NIHR in the last 3 years, related to research in the Deaf population. GES and SD declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

This study performed a secondary analysis of existing data and thus no participants were recruited. In the prior study, from which the data were taken, ethics approval was received from the University of Manchester Research Ethics Committee (REC) (reference number: 14183). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

In the prior study, all participants who completed the EQ5D-5L BSL gave individual informed consent and that they gave consent for secondary data analysis of anonymised results, ethics approval was received from the University of Manchester Research Ethics Committee (REC) (reference number: 14183).

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shields, G.E., Rogers, K.D., Young, A. et al. Health State Values of Deaf British Sign Language (BSL) Users in the UK: An Application of the BSL Version of the EQ-5D-5L. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 18, 547–556 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-019-00546-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-019-00546-8