Abstract

Mepilex Border Sacrum and Heel dressings are self-adherent, multilayer foam dressings designed for use on the heel and sacrum aiming to prevent pressure ulcers. The dressings are used in addition to standard care protocols for pressure ulcer prevention. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) selected Mepilex Border Sacrum and Heel dressings for evaluation. The External Assessment Centre (EAC) critiqued the company’s submission. Thirteen studies (four randomised controlled trials and nine nonrandomised comparative studies) were included. The majority of studies compared Mepilex Border Sacrum dressings (plus standard care) with standard care alone. Comparative evidence for Mepilex Border Heel dressings was limited. A meta-analysis indicated a non-statistically significant difference in favour of Mepilex Border Sacrum dressings for pressure ulcer incidence [RR 0.51 (95% CI 0.22–1.18)]. The company produced a de novo cost model, which was critiqued by the EAC. After the EAC updated input parameters, cost savings of £19 per patient compared with standard care alone for pressure ulcer prevention were estimated with Mepilex Border dressings predicted to be cost saving in 57% of iterations. The Medical Technologies Advisory Committee reviewed the evidence and judged that, although Mepilex Border Heel and Sacrum dressings have potential to prevent pressure ulcers in people who are considered to be at risk in acute care settings, further evidence is required to address uncertainties around the claimed benefits of the dressings and the incidence of pressure ulcers in an NHS acute-care setting. After a public consultation, NICE published this as Medical Technology Guidance 40.

Similar content being viewed by others

Mepilex Border Heel and Sacrum dressings show promise for preventing pressure ulcers in people who are considered to be at risk in acute-care settings. However, there is currently insufficient evidence to support the case for routine adoption in the NHS. |

Research is recommended to address uncertainties about the claimed benefits of using Mepilex Border Heel and Sacrum dressings. This research should also explore issues such as: |

the incidence of heel and sacrum pressure ulcers in NHS acute-care settings |

criteria for patient selection to reduce pressure ulcer incidence with Mepilex Border Heel and Sacrum dressings in addition to standard care. |

1 Introduction

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) evaluates medical technologies and, where appropriate, produces evidence-based guidance to encourage adoption of novel and innovative medical devices and diagnostics within the National Health Service (NHS) in England. NICE’s Medical Technologies Evaluation Programme (MTEP) receives notifications of medical technologies, most commonly from product manufacturers, which are selected for evaluation based on criteria, including whether they have the potential to offer clinical benefits to patients and/or reduce costs compared with standard care.

A scope is produced by NICE detailing the decision problem to be addressed, and clinical and economic evidence submitted by the company is assessed independently by an External Assessment Centre (EAC). Following the EAC’s evaluation and public consultation period, the Medical Technologies Advisory Committee (MTAC) develops guidance. The methodology adopted by the MTEP is described in more detail in its methods and process guides [1, 2].

In January 2019, NICE issued final guidance on Mepilex Border Sacrum and Heel dressings for use with patients at risk or at high risk of pressure ulcers. Mepilex Border Sacrum and Heel dressings are self-adherent, five-layer foam dressings specifically for use on the heel and sacrum. The dressings have been designed to reduce friction between the skin and the dressing, prevent stretch or tear of the skin and absorb moisture, with the aim of preventing the occurrence of pressure ulcers. The EAC critiquing the evidence was the Newcastle upon Tyne NHS Foundation Trust and York Health Economics Consortium partnership. Clinical experts, identified using NICE’s published processes, provided advice to the EAC and MTAC.

This article includes an overview of the clinical and cost-effectiveness evidence submitted by the company, the EAC’s report and the subsequent development of the NICE guidance. Full documentation of the process, final guidance and supporting evidence is available on the NICE website [3].

2 Background to the Indication and Devices

Pressure ulcers are localised injuries to the skin and/or underlying tissue as a result of pressure, or pressure in combination with shear [4]. Pressure ulcers can range in severity and can be classified into the following categories or stages [5]:

-

Stage 1 Intact skin with non-blanchable erythema of a localised area. Discoloration of the skin, warmth, oedema, hardness or pain may also be present.

-

Stage 2 Partial thickness loss of dermis presenting as a shallow open ulcer with a red/pink wound bed, without slough or bruising. It may also present as an intact or open/ruptured serum-filled blister.

-

Stage 3 Full thickness tissue loss. Subcutaneous fat may be visible, but bone, tendon or muscle are not exposed. Some slough may be present. It may include undermining and tunnelling.

-

Stage 4 Full thickness tissue loss with exposed bone, tendon or muscle. Slough or eschar may be present. It often includes undermining and tunnelling.

Pressure ulcers can have a significant impact on a patient’s quality of life, both physically and psychologically. They can also lead to further health complications such as infection, extended hospital stays, restricted rehabilitation and restricted treatment options for other medical conditions [6, 7].

All patients are at risk of pressure ulcers. However, Mepilex Border dressings have been indicated for use in people identified as either ‘at risk’ or ‘at high risk’ of developing a pressure ulcer.

Guy [8] reports that risk factors for pressure ulcers include:

-

Reduced mobility or immobility—pain is a warning signal that pressure has been exerted for too long, which normally triggers movement. Patients who are unable to move will require the help of someone else in order to do so.

-

Lack of sensation—if pain signals are absent, patients may not be aware that damage is occurring and will not realise that they should move. This includes anything which may impair sensation including unconsciousness, analgesia or alcohol/substance abuse.

-

Nutritional status—it is widely accepted that undernourished people are at increased risk of pressure ulcer development.

-

Compromised vascular supply—skin with compromised vascular supply may deteriorate more rapidly. Patients with peripheral arterial disease, or patients who experience events such as cardiac arrest or hypovolaemic shock may be at increased risk.

-

Moisture—skin that is constantly or often moist is at increased risk of pressure ulcer.

-

Friction and shear—these forces are additional to pressure, and further hamper blood flow by stretching and contorting blood vessels. This is most commonly seen in the sacrum and heels.

In addition to the risk factors described above, clinical experts also indicated that the following conditions may also increase the risk of developing a pressure ulcer: diabetes, dementia, significant cognitive impairment, tremors, leg spasms, leg oedema, critical illness, low or high body mass index (BMI), terminal illness, extremes of age, previous history of pressure damage and long theatre times.

Risk assessment tools such as the Braden scale, the Waterlow score and the Norton risk-assessment scale are recommended by NICE to be used alongside clinical judgement to determine whether a person is at increased risk of developing a pressure ulcer [9].

In addition to risk assessment for all people admitted to secondary care, standard care protocols for prevention of pressure ulcers recommended by NICE [9] include:

-

Skin assessment either once daily or more often for those assessed as being at high risk of a pressure ulcer, and less frequently for those at lower risk.

-

Repositioning at least every 6 h for people at risk, or every 4 h for people at high risk of developing a pressure ulcer.

-

Use of specialist equipment such as high-specification foam mattresses/cushions and/or devices to offload heel pressure.

-

Use of barrier creams in people at high risk of developing a moisture lesion or incontinence-associated dermatitis, as identified by skin assessment.

Mepilex Border dressings are intended for use in addition to standard care protocols for pressure ulcer prevention.

3 Decision Problem (Scope)

3.1 Population

The population described in the scope included patients at risk or at high risk of pressure ulcers in an acute care setting as defined using a validated assessment scale. The company also included evidence on patients in an aged-care setting; however, this was subsequently excluded by the EAC in line with the scope. The majority of evidence identified by both the company and the EAC was in high-risk patients.

3.2 Intervention

Interventions identified in the scope were Mepilex Border Heel dressings and Mepilex Border Sacrum dressings used as an adjunct to standard NHS clinical practice. The company (Mölnlycke Health Care) included evidence on Mepilex Border general dressings (not specific to heel or sacrum) and Mepilex dressings (a 3-layer version of the Mepilex Border dressing). The EAC included evidence on Mepilex Border general dressings (when applied to the heel or sacrum) but excluded evidence on the Mepilex three-layer dressings as these were deemed to be out of scope given that they are a separate device utilising different technology.

3.3 Comparator

The comparator listed in the scope was standard NHS clinical practice for patients considered ‘at risk’ or ‘at high risk’ of pressure ulcers, which may involve a combination of:

-

Risk assessment with a validated scale.

-

Skin assessment.

-

Frequent repositioning.

-

Pressure redistribution devices such as high-specification foam mattresses.

-

Other dressings or skin applications.

-

Information.

-

Barrier cream.

Evidence submitted by the company included studies conducted in countries outside of the UK and, therefore, standard care varied across studies and was not always consistent with the scope. Neither the company nor the EAC identified any comparative UK evidence.

3.4 Outcomes

The company’s submission addressed five of the ten outcomes identified in the scope. Specifically, evidence was provided for the incidence of pressure ulcers, stage of pressure ulcers, level of patient satisfaction, level of pain and discomfort and impact on quality of life, and ease of use of product. No evidence was identified by either the company or the EAC on the following outcomes specified in the scope: incidence of skin breakdown at the heel and sacrum, additional length of hospital stay as a result of pressure ulcers, patient compliance with pressure ulcer prevention strategies, complications avoided from pressure ulcer prevention strategies and device-related adverse events.

4 Review of Clinical and Economic Evidence

Section 4.1 summarises the clinical evidence submitted, the EAC’s critique of the clinical evidence and the EAC’s additional work. Section 4.2 provides the same detail for the economic evidence.

4.1 Clinical Effectiveness Evidence

4.1.1 Company’s Review of Clinical Effectiveness Evidence

The company identified 203 records through its literature search and included 34 studies reported across 35 records, comprising:

-

Five randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including four [10,11,12,13] published and one unpublished. Since the company submitted its report, a full publication became available for the unpublished trial [14].

-

Twenty-two observational studies, including 14 published [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28] and 8 unpublished [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36].

The company completed the relevant results and methodology tables for each included study and attempted to critically appraise the evidence. The company did not synthesise the outcomes using a meta-analysis. Instead, a narrative synthesis of study results was provided, and the company commented on the synthesis conducted in several published systematic reviews.

4.1.2 Critique of Clinical Effectiveness Evidence

The EAC identified several limitations to the company’s search methodology, and their selection criteria were not in full alignment with the NICE scope. The EAC re-ran the company’s literature search as far as possible, conducted a de novo search and realigned the selection criteria with the scope to identify relevant clinical evidence on Mepilex Border Heel, Mepilex Border Sacrum and Mepilex Border (when applied to the heel or sacrum) dressings. Full details of the EAC’s search strategies are described in the assessment report [41]. The EAC identified 1242 records, which were assessed by 2 reviewers (see Fig. 1).

Due to the sufficient volume of comparative evidence identified, the EAC limited eligible study designs to RCTs and non-randomised comparative studies. Single-arm studies were considered for adverse events only. Thirteen studies reported across 23 records were eligible for inclusion in the review. The reviewed evidence comprised:

-

Four RCTs. Three of which were identified and included by the company [10, 11, 13] and one newly identified by the EAC [42].

-

Nine comparative observational studies [17,18,19, 23,24,25, 28, 33, 36]. All of these studies were identified and included by the company.

All of the studies included by the company were successfully identified by the EAC. However, 22 studies (2 RCTs [12, 14, 25], 2 non-randomised comparative observational studies [21, 22], 12 single-arm studies [15, 16, 20, 26, 27, 29,30,31,32, 34, 35, 43] and 7 systematic reviews [37,38,39,40, 44,45,46]) were subsequently excluded based on the EAC’s updated eligibility criteria. Detailed reasons for excluding these studies and detailed information on the studies included by the EAC are reported in the EAC’s assessment report [41].

The four included RCTs were published as full papers and compared Mepilex Border Sacrum plus standard care with standard care alone [10, 11, 13, 42]. Standard care varied across the RCTs, but specific components that aligned with the scope included pressure redistribution [10, 11, 13, 42], regular repositioning and skin care [10, 11], skin assessment [42] and risk assessment by Braden score [13]. The populations in all four RCTs were well matched with the scope of the decision problem, recruiting adult patients at high risk of pressure ulcers in acute care settings. All four trials were conducted outside of the UK.

Seven of the nine non-randomised comparative studies compared Mepilex Border Sacrum [17,18,19, 24], Mepilex Border Heel [13, 33] or Mepilex Border [23] dressings plus standard care with standard care alone. One study compared Mepilex Border with a hydrocolloid dressing, both in conjunction with standard care [36]. One study conducted a bilateral comparison of Mepilex Border and a polyurethane film dressing applied to the chest and heel [28]. There was a wide variation in standard care across the studies, with the majority utilising a mixture of components aligned with the scope. The studies were generally well matched with the scope in terms of their populations and recruitment, recruiting patients at risk or high risk of pressure ulcers in acute care settings. All nine studies were conducted outside the UK.

The EAC judged that all of the RCTs provided an acceptable level of internal and external validity with the exception of one trial [11], which had high internal validity and acceptable external validity. Only three observational studies [23,24,25] had an acceptable rating for both internal and external validity.

The studies reported few outcomes of interest that were specified in the scope. The most commonly reported outcomes were the incidence rate and severity of pressure ulcers as assessed using established guidelines [4, 5]. The EAC synthesised the results from three RCTs comparing Mepilex Border Sacrum to standard care using a fixed-effect meta-analysis in relation to the number of patients developing pressure ulcers. The pooled estimate showed a non-statistically significant difference [RR = 0.51 (95% CI 0.22–1.18), p = 0.12] in favour of Mepilex Border Sacrum (see Fig. 2). Results from one study assessing Mepilex Border Heel and one study assessing Mepilex Border showed a statistically significant difference in favour of the intervention (p ≤ 0.001) for pressure ulcer incidence. Where results relating to the stage of pressure ulcers were reported, higher stage pressure ulcers typically developed in patients not receiving the intervention.

Limited evidence was available for other outcomes. In terms of patient comfort and satisfaction, results from one trial showed that in the majority of self-assessments, patients reported the intervention as comfortable [42]. In terms of usability, one study stated that there were some difficulties associated with reapplying the dressing and keeping it in place when patients were restless [25]. Very limited data were reported across the studies in relation to complications and device-related adverse events.

The EAC concluded that, despite a relatively large body of clinical evidence, there remains uncertainty in the treatment effect of Mepilex Border dressings. In particular, there are limited data for Mepilex Heel and Mepilex Border general (applied to the heel or sacrum) dressings, patients ‘at risk’ but not ‘at high risk’ of pressure ulcers, and paediatric patients. Further, many of the outcomes of interest to the decision problem are not addressed by the evidence.

4.2 Economic Evidence

4.2.1 Company’s Economic Submission

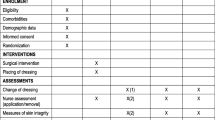

The company submitted a de novo cost model comparing Mepilex Border Sacrum and Heel dressings plus standard care pressure ulcer prevention with standard care pressure ulcer prevention alone. The EAC deemed the development of a de novo model appropriate given the lack of published UK economic evidence. The analysis had a time horizon of under one year and was conducted from an NHS and Personal Social Services perspective. A fully executable model was produced in Microsoft Excel. The model had a simple decision tree structure, where a patient could either develop a pressure ulcer or not develop a pressure ulcer. The company primarily used data from one RCT, which was conducted in Australia, to populate clinical effectiveness parameters for both the Mepilex Border dressings plus standard-care arm and the standard-care alone arm. Standard-care prevention protocols were not explicitly modelled as the costs were assumed to be equivalent between both arms. A cost-benefit analysis, also conducted in Australia, was used to populate resource use parameters for Mepilex Border dressings including the number of dressings used and nurse time for changing the dressings. All model input parameters used in the company’s model are shown in Table 1.

Base-case results from the company’s model estimated that Mepilex Border dressings generated cost savings of £177 per patient, based on total per patient costs of £231 in the Mepilex Border dressings arm and £408 in the standard-care arm. Scenario based and deterministic sensitivity analysis was conducted by the company including best- and worst-case scenarios which examined the impact of varying the incidence of pressure ulcers with Mepilex Border dressings. The majority of analyses returned cost saving results; however, not all parameters were included in the sensitivity analyses.

4.2.2 Critique of Economic Evidence

The EAC judged the structure of the company’s model to be appropriate to the decision problem, capturing the relevant costs and consequences of the dressings. The time horizon of less than 1 year was considered appropriate given that even stage 4 pressure ulcers are expected to heal within 155 days [47]. The company’s model did not include any implementation or training costs associated with the introduction of the dressings. This was judged to be appropriate by the EAC because free training is provided by the company and staff time associated with this was considered to be negligible on a per patient basis. Adverse events were also excluded from the company’s model. Very little evidence of adverse events was identified by the EAC and, where these were identified, they were associated with very little or no cost. Consequently, the exclusion of adverse events from the economic model was considered appropriate by the EAC. The EAC replicated the company’s calculations in order to confirm their accuracy and identified an error in the way staff costs had been applied in the company’s model, causing them to be overestimated.

The key critique of the company’s model was that more appropriate data could have been used to demonstrate the baseline incidence of pressure ulcers and clinical effectiveness of the dressings. All model inputs were validated by the EAC using expert advice and published literature. The majority of input parameters were amended by the EAC, as shown in Table 2.

Key clinical parameters in the model were the incidence of pressure ulcers, both with standard care alone and with standard care plus Mepilex Border dressings. The company used data from one RCT conducted in a single centre in Australia to populate the input parameters for both arms in the model [13]. The trial did not give a detailed description of standard care and, therefore, it was not possible to ascertain how well this compared with standard care in the UK and, consequently, how well the results of the trial could be generalised to an NHS setting. The EAC deemed it more appropriate to identify a baseline incidence of pressure ulcers from a UK-specific source for use in the standard-care arm. This was then combined with a relative risk from the meta-analysis to derive a risk of pressure ulcers in the standard care plus Mepilex Border dressings arm.

The source used for the cost of pressure ulcer treatment in the company’s model, although UK-specific, was outdated. A more recent source was identified and used by the EAC. The company also weighted the pressure ulcer treatment costs by the stage of pressure ulcers developed, as reported by Santamaria et al. [13]. Given the low event numbers in this and other trials, this method was deemed by the EAC to be too uncertain. Therefore, the EAC used a UK-specific source with high event numbers to weight the costs by stage. The staging of pressure ulcers was assumed to be equal in both treatment arms because it was not possible to ascertain from the clinical evidence whether the stage of pressure ulcer was affected by the Mepilex Border dressings.

The number of dressing changes in the company’s model was based on Santamaria et al. [13], an RCT conducted in Australia. This was amended by the EAC using data from a single arm observational study conducted in the UK because this was judged to be more reflective of resource use in the NHS. Minor amendments were also made to other resource use parameters, including staff costs and dressing costs, in order to incorporate the most up-to-date data. In addition, ranges and distributions of input parameters were amended by the EAC to those it deemed most appropriate.

4.2.3 Additional Work Undertaken by EAC Relating to Economic Evidence

A targeted literature search was conducted by the EAC to identify a UK-specific incidence of pressure ulcers in a population at risk or at high risk of pressure ulcer. The NHS safety thermometer was deemed to be the most useful source by the EAC because, although a voluntary scheme, most NHS trusts submit data every month on the prevalence of pressure ulcers, along with other safety measures [48]. Prevalence of new pressure ulcers is reported (whereby data are recorded on one day each month only and new pressure ulcers are those that have occurred since the last month). The EAC used this value as a proxy for incidence of pressure ulcers. Due to limitations associated with the data, the EAC adjusted the value from the NHS safety thermometer to account for known under-reporting and the fact that only stage 2 or higher pressure ulcers were reported [49, 50]. The value was further adjusted to include only pressure ulcers on the heel and sacrum [50].

The targeted search conducted by the EAC also aimed to identify evidence on the cost of treating pressure ulcers in the UK. Four studies were included, the most useful of which was a costing study by Dealey et al. [51]. This study costed the treatment of pressure ulcers by stage using a ‘bottom-up’ methodology. This was based on the resources required to deliver protocols of care reflecting good clinical practice, with prices reflecting the costs to the health and social care system in the UK. To calculate a cost weighted by stage of pressure ulcer, the EAC used the proportion of pressure ulcers falling into each stage from the NHS safety thermometer data, adjusted for missed stage 1 pressure ulcers [48, 50].

As well as updating the inputs in the company’s model, the EAC ran a number of additional sensitivity and scenario analyses. All parameters were varied individually within plausible ranges identified by the EAC, as detailed in Table 2. The majority of parameters varied within these ranges resulted in increased costs associated with the use of Mepilex Border dressings, indicating uncertainty around individual input parameters. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was included by the EAC to account for combined uncertainty in parameters. PSA was run with 2000 iterations and included two scenarios. First, pressure ulcer treatment costs were varied for both the standard care and Mepilex Border dressings arms together, i.e. assuming the stage of pressure ulcer was unaffected by the dressings. Second, pressure ulcer treatment costs were varied for each of the treatment arms independently, i.e. assuming that Mepilex Border dressings may result in higher or lower stages of pressure ulcer on average. A scenario analysis was run to explore the effect of using the alternative relative risk calculated in the meta-analysis, which included the four RCTs identified in the EAC’s clinical review. This analysis was subject to the strong assumption that the data from Santamaria et al. [13] equate to one pressure ulcer per patient. Scenarios were also run for use of the sacrum and heel dressings separately, whereby the input parameters relating to dressing and staff costs and baseline incidence of pressure ulcers were amended to reflect each location of pressure ulcer and dressing variant. A further scenario analysis was run to explore the impact of using the Mepilex Border general dressing (shape not specific to heel or sacrum) used on the heel and sacrum. This scenario assumed the clinical efficacy and resource use parameters were equivalent with the other dressing variants, and only the costs of the dressings were amended.

Following the EAC’s updates, Mepilex Border dressings in combination with standard care were estimated to result in cost savings of £19 per patient. This was based on total per patient costs of £162 in the Mepilex Border dressings arm and £181 in the standard care arm. PSA predicted the dressings would be cost saving in 57% of model iterations regardless of whether pressure ulcer treatment costs were varied independently or together. All scenarios resulted in increased cost savings associated with use of the dressings (£25–£48 per patient).

5 NICE Guidance

5.1 Provisional Recommendations

The evidence submitted by the company and the EAC’s critique of this evidence was presented to the MTAC, who provided draft recommendations relating to Mepilex Border dressings following their meeting in June 2018. These were as follows:

-

Mepilex Border Heel and Sacrum dressings show promise for preventing pressure ulcers in people considered to be at risk in acute care settings. However, there is currently insufficient evidence to support the case for routine adoption in the NHS.

-

Research is recommended to address uncertainties around the claimed benefits of using Mepilex Border Heel and Sacrum dressings. This research should also explore the incidence of sacrum and heel pressure ulcers in NHS acute care settings, and the outcomes from using Mepilex Border Heel and Sacrum dressings in addition to standard care.

5.2 Consultation Response

During the consultation, NICE received 12 consultation comments from two consultees (the company and an NHS professional). Comments regarding the variability in estimates of pressure ulcer incidence and the under-reporting of pressure ulcers in the NHS safety thermometer attracted a significant amount of discussion. The committee sought expert advice on these comments and concluded that based on available data, the EAC’s use of the safety thermometer data was appropriate.

The provisional recommendation noting a lack of evidence to support routine adoption was challenged by the company, who cited that international guidelines have made recommendations supporting the use of polyurethane dressings for pressure ulcer prevention. The committee considered that the provisional recommendation was driven by data in the UK rather than data and methods which informed the international guideline. The committee also considered that medical technologies guidance only considers evidence in support of the claimed benefits of a single technology rather than a broad review addressing multiple similar technologies. In addition, none of the expert advice the committee heard regarding this issue suggested an amendment to the provisional recommendation.

There is a lack of guidance on patient selection. The committee heard from expert advisers that in practice patient selection is not based on a set of rules such as the World Union of Wound Healing Societies (WUWHS) algorithm because care is often individualised. No amendment was made as a result of comments relating to the meta-analysis done by the EAC. Minor changes were made to clarify the description of the technology.

6 Key Challenges and Learning Points

The key challenges faced by the EAC and the company were the issues with generalisability and uncertainty surrounding the clinical evidence. Although a reasonable body of evidence exists for Mepilex Border dressings, all of the clinical trials were conducted outside of a UK setting. This raised uncertainty around whether the evidence from these trials could be generalised to the UK NHS, due to potential differences in standard care pressure ulcer prevention protocols and the baseline incidence rate of pressure ulcers. Standard care prevention protocols were not always clear in the reporting of each of the clinical trials, although in cases where they were clear, it was judged that they were consistent with standard care in the UK. Expert advice and the existence of national prevention guidelines further supported the idea that the comparator in the trials was well matched to the decision problem [4]. The baseline incidence of pressure ulcers estimated for the UK NHS setting by the EAC was also well aligned with the three RCTs on which the meta-analysis was based, and therefore, the scope to benefit from Mepilex Border dressings was judged to be broadly similar in a UK NHS setting.

Further issues associated with generalisability of the clinical evidence related to the patient population in which evidence was generated. The majority of the clinical evidence came from studies in a high-risk population and there was limited evidence in lower-risk groups. Further, there was also a lack of evidence using the Mepilex Border Heel variant of the dressing, with all key trials assessing the Mepilex Border Sacrum variant and only one non-randomised comparative trial assessing the effects of the Mepilex Border Heel variant of the dressing.

Obtaining an accurate estimate of the baseline incidence of pressure ulcers was difficult. Whilst the NHS safety thermometer reports useful information, this was limited by likely under-reporting and the exclusion of stage 1 pressure ulcers. As described in Sect. 4.2.3, the EAC used information from the literature to refine this estimate [48, 50]. Despite these efforts, there remained uncertainty in the estimate, and clinical experts noted the variation in incidence of pressure ulcers between settings and NHS Trusts. However, the use of observational or “real world” evidence allowed for a more reasonable estimate of baseline pressure ulcer incidence for the UK NHS setting than would have been obtained from using information from the RCTs instead.

A further challenge was the lack of data and uncertainty surrounding some key parameters. After pooling the results of three of the key RCTs, although the point estimate was in favour of Mepilex Border Sacrum dressings, the difference remained statistically insignificant. Additionally, there was very limited evidence on the number of dressings required per patient to prevent a pressure ulcer, and therefore there was also uncertainty around resource use such as nurse time associated with application of the dressings. For this reason, the costs associated with use of the dressings remain relatively uncertain. It was also not possible to ascertain whether the dressings had any impact on the stage of pressure ulcer developed due to low event numbers in the trial. Therefore, any differences between the two arms in the costs of treating pressure ulcers could not be captured in the analysis.

7 Conclusion

The MTEP evaluation process was followed for the development of medical technologies guidance on Mepilex Border Heel and Sacrum dressings. This included a submission of clinical and economic evidence by the company, critical appraisal of this evidence by the EAC, additional work to capture available evidence relating to the decision problem and address remaining uncertainties, drafting of recommendations by the MTAC, and a subsequent consultation. Following this process, the MTAC judged that Mepilex Border Heel and Sacrum dressings have the potential to prevent pressure ulcers in people who are considered to be at risk in acute care settings, but that further evidence is required to address uncertainties around the claimed benefits of the dressings and the incidence of pressure ulcers in an NHS acute care settings.

References

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Medical technologies evaluation programme methods guide. London: NICE; 2017.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Medical technologies evaluation programme process guide. London: NICE; 2017.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Mepilex Border Heel and Sacrum dressings for preventing pressure ulcers. 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mtg40. Accessed 11 Jan 2019.

National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: quick reference guide. Haesler E, editor. Australia: Cambridge Media, Perth; 2014. http://www.npuap.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Quick-Reference-Guide-DIGITAL-NPUAP-EPUAP-PPPIA.pdf

National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. international guideline: pressure ulcer treatment technical report. 2009.

Gorecki C, Brown JM, Nelson EA, Briggs M, Schoonhoven L, Dealey C, et al. Impact of pressure ulcers on quality of life in older patients: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(7):1175–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02307.x.

Gorecki C, Brown JM, Cano S, Lamping DL, Briggs M, Coleman S, et al. Development and validation of a new patient-reported outcome measure for patients with pressure ulcers: the PU-QOL instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:95. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-11-95.

Guy H. Pressure ulcer risk assessment. Nurs Times. 2012;108(4):16 (8–20).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Pressure ulcers: prevention and management. 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg179. Accessed 13 Apr 2018.

Aloweni F, Lim ML, Chua TL, Tan SB, Lian SB, Ang SY. A randomised controlled trial to evaluate the incremental effectiveness of a prophylactic dressing and fatty acids oil in the prevention of pressure injuries. Wound Pract Res. 2017;25(1):24–34.

Kalowes P, Messina V, Li M. Five-layered soft silicone foam dressing to prevent pressure ulcers in the intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care. 2016;25(6):e108–19. https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2016875.

Bao Q, Ji Q. Observation on effect of Mepilex on the prevention and treatment of pressure sores. Chin J Med Nurs. 2010. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-00845036/full.

Santamaria N, Gerdtz M, Sage S, McCann J, Freeman A, Vassiliou T, et al. A randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of soft silicone multi-layered foam dressings in the prevention of sacral and heel pressure ulcers in trauma and critically ill patients: the border trial. Int Wound J. 2015;12(3):302–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12101.

Santamaria N, Gerdtz M, Kapp S, Wilson L, Gefen A. A randomised controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness of multi-layer silicone foam dressings for the prevention of pressure injuries in high-risk aged care residents: the border III trial. Int Wound J. 2018;15:482–90.

Bateman SD, Roberts S. Moisture lesions and associated pressure ulcers: getting the dressing regimen right. Wounds UK. 2013;9(2):97–102.

Brindle CT. Outliers to the Braden Scale: identifying high-risk ICU patients and the results of prophylactic dressing use. World Counc Enteros Ther J. 2010;30(1):11–8.

Brindle CT, Wegelin JA. Prophylactic dressing application to reduce pressure ulcer formation in cardiac surgery patients. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs. 2012;39(2):133–42. https://doi.org/10.1097/WON.0b013e318247cb82.

Chaiken N. Reduction of sacral pressure ulcers in the intensive care unit using a silicone border foam dressing. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs. 2012;39(2):143–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/WON.0b013e318246400c.

Cubit K, McNally B, Lopez V. Taking the pressure off in the Emergency Department: evaluation of the prophylactic application of a low shear, soft silicon sacral dressing on high risk medical patients. Int Wound J. 2013;10(5):579–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-481X.2012.01025.x.

Johnstone A, McGown K. Innovations in the reduction of pressure ulceration and pain in critical care. Wounds UK. 2013;9(3):80–4.

Koerner S. Does the use of an absorbent soft silicone self-adherent bordered foam improve quality of care by decreasing incidence of hospital acquired pressure ulcers? In: Scientific and clinical abstracts from the 43rd annual wound, ostomy and continence nurses conference, New Orleans, Louisiana; June 4–8; New Orleans, Louisiana; 2011. p. 5315.

Padula WV. Effectiveness and value of prophylactic 5-layer foam sacral dressings to prevent hospital-acquired pressure injuries in acute care hospitals: an observational cohort study. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs. 2017;44(5):413–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/WON.0000000000000358.

Park KH. The effect of a silicone border foam dressing for prevention of pressure ulcers and incontinence-associated dermatitis in intensive care unit patients. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs. 2014;41(5):424–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/WON.0000000000000046 [Erratum appears in J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2014 Nov–Dec;41(6):580].

Richard-Denis A, Thompson C, Mac-Thiong J-M. Effectiveness of a multi-layer foam dressing in preventing sacral pressure ulcers for the early acute care of patients with a traumatic spinal cord injury: comparison with the use of a gel mattress. Int Wound J. 2017;14(5):874–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12710.

Santamaria N, Gerdtz M, Liu W, Rakis S, Sage S, Ng AW, et al. Clinical effectiveness of a silicone foam dressing for the prevention of heel pressure ulcers in critically ill patients: border II trial. J Wound Care. 2015;24(8):340–5. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2015.24.8.340.

Sullivan R. Use of a soft silicone foam dressing to change the trajectory of destruction associated with suspected deep tissue pressure ulcers. Medsurg Nurs. 2015;24(4):237–42 (67).

Walsh NS, Blanck AW, Smith L, Cross M, Andersson L, Polito C. Use of a sacral silicone border foam dressing as one component of a pressure ulcer prevention program in an intensive care unit setting. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs. 2012;39(2):146–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/WON.0b013e3182435579.

Yoshimura M, Ohura N, Tanaka J, Ichimura S, Kasuya Y, Hotta O, et al. Soft silicone foam dressing is more effective than polyurethane film dressing for preventing intraoperatively acquired pressure ulcers in spinal surgery patients: the Border Operating room Spinal Surgery (BOSS) trial in Japan. Int Wound J. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12696 (EPub ahead of print).

Baker G. Nursing driving excellence: preventing pressure ulcers in the high-risk population (poster presentation). In: Symposium on advance wound care fall; Las Vegas, Nevada, United States of America; 2014.

Daukste M. Mepilex border sacrum dressing use for pressure ulcers prevention in period of open heart surgery and ICU. Cardiology. 2013;1:33. https://doi.org/10.1159/000351756.

Edwards MB, Lynch JH. Head over heels for prevention: use of a silicone bordered foam heel dressing in the prevention of pressure ulcers (poster presentation). In: Symposium on advanced wound care fall; Las Vegas, Nevada, United States of America; 2014.

Gentry T, Wright A. The ‘sacral heart’ dressing study: use of an absorbent self-adherent soft silicone sacral foam dressing across acute care settings (poster presentation). In: The joint conference of the Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society and the World Council of Enterostomal Therapists; Phoenix, Arizona, United States of America; 2010.

Haisley V, Potter K, Wallace J, George R, Betsill K. An ounce of prevention: the use of a soft silicone five-layer bordered foam heel dressing to decrease the incidence of hospital-acquired heel pressure ulcers in an acute care setting. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs. 2015;42(3):S48–9.

Lientz J, editor. Dollars and sense: economic value in HAPU/sDTI prevention (poster presentation). In: National pressure ulcer advisory panel biennial conference; Houston, Texas, United States of America; 2013.

Muldoon C, Grossman N, Lawrence P. Initial use absorbent soft silicone self-adherent bordered foam dressing reduces sacral pressure ulcers in the cariovascular ICU (poster presentation). In: The joint conference of the Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society and the World Council of Enterostomol Therapists; Phoenix, Arizona, United States of America; 2010.

Jin HE. Pressure ulcer prevention using a multi-layer foam dressing with soft silicone (Mepilex Border) during off-pump coronary artery bypass graft (OPCABG) surgery. 2018 (unpublished).

Black J, Clark M, Dealey C, Brindle CT, Alves P, Santamaria N, et al. Dressings as an adjunct to pressure ulcer prevention: consensus panel recommendations. Int Wound J. 2015;12(4):484–8.

Clark M, Black J, Alves P, Brindle CT, Call E, Dealey C, et al. Systematic review of the use of prophylactic dressings in the prevention of pressure ulcers. Int Wound J. 2014;11(5):460–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/iwj.12212.

Cornish L. The use of prophylactic dressings in the prevention of pressure ulcers: a literature review. Br J Community Nurs. 2017;22(Suppl 6):S26–32. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2017.22.Sup6.S26.

Huang L, Woo KY, Liu LB, Wen RJ, Hu AL, Shi CG. Dressings for preventing pressure ulcers: a meta-analysis. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2015;28(6):267–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ASW.0000463905.69998.0d.

Marshall C, Shore J, Arber M, Cikalo M, Peel A, McCool R et al. Mepilex Border Heel and Sacrum dressings for preventing pressure ulcers (assessment report). 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mtg40/documents/assessment-report.

Walker R, Huxley L, Juttner M, Burmeister E, Scott J, Aitken LM. A pilot randomized controlled trial using prophylactic dressings to minimize sacral pressure injuries in high-risk hospitalized patients. Clin Nurs Res. 2017;26(4):484–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773816629689.

ClinicalTrials.gov. Pressure injury prevention in the ICU with multi-layer foam dressings (PUP16_01). Identifier NCT02962882. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); 2018. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02962882.

Moore ZEH, Webster J. Dressings and topical agents for preventing pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8:CD009362.

National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel EPUAPaPPPIA. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: clinical practice guideline. Haesler E, editor. Perth, Australia: Cambridge Media; 2014.

Tayyib N, Coyer F. Effectiveness of pressure ulcer prevention strategies for adult patients in intensive care units: a systematic review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2016;13(6):432–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12177.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Pressure ulcers: prevention and management. Appendix L. 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg179/evidence/appendix-l-pdf-19713978326. Accessed 13 Apr 2018.

NHS Improvement. NHS safety thermometer. In: Classic. 2017–2018. https://www.safetythermometer.nhs.uk/index.php/classic-thermometer. Accessed May 2018.

Smith IL, Nixon J, Brown S, Wilson L, Coleman S. Pressure ulcer and wounds reporting in NHS hospitals in England part 1: audit of monitoring systems. J Tissue Viability. 2016;25(1):3–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtv.2015.11.001.

Clark M, Semple MJ, Ivins N, Mahoney K, Harding K. National audit of pressure ulcers and incontinence-associated dermatitis in hospitals across Wales: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e015616. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015616.

Dealey C, Posnett J, Walker A. The cost of pressure ulcers in the United Kingdom. J Wound Care. 2012;21(6):261–2. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2012.21.6.261 (4, 6).

Santamaria N. Preventing pressure ulcers in aged care: a randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of prophylactic silicone foam dressings. In: 18th EPUAP annual meeting of the European pressure ulcer advisory panel; Ghent, Belgium; 2015. p. 22.

Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU). Unit costs of health & social care 2017. Canterbury: University of Kent; 2017.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the clinical experts identified by NICE, who provided expertise and clinical knowledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was prepared by CM and JS with contributions from MA, MC, TO, AP, RM and MJ. Literature searching was undertaken by MA and evidence review by CM and MC, with advice and quality assurance from RM and MJ. The model critique was undertaken by JS and AP, with advice and quality assurance from MJ. TO reported the decision problem and the NICE recommendations. The guarantor for overall content is MJ.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals and York Health Economics Consortium are funded by NICE to act as an EAC for the Medical Technologies Evaluation Programme.

Conflict of interest

This summary of the Medical Technology Guidance was produced following publication of the final guidance report. This summary has not been externally peer reviewed by Applied Health Economics and Health Policy. Seven of the authors (CM, JS, MA, MC, AP, RM and MJ) work or worked for the EAC, but otherwise have no conflicts of interest. TO is an employee of NICE.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Marshall, C., Shore, J., Arber, M. et al. Mepilex Border Sacrum and Heel Dressings for the Prevention of Pressure Ulcers: A NICE Medical Technology Guidance. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 17, 453–465 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-019-00465-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-019-00465-8