Abstract

Introduction

Migraine is under-diagnosed and under-treated. Many people with migraine do not seek medical care, and those who do may initially receive a different diagnosis and/or be dissatisfied with provided care on their journey before treatment with a CGRP-mAb (calcitonin-gene-related-peptide monoclonal antibody).

Methods

This is a cross-sectional, self-reported, online survey of subjects in Lilly’s Emgality® Patient Support Program in 2022. Questionnaires collected insights into subjects’ prior experiences with migraine and interactions with healthcare professionals before receiving CGRP-mAbs.

Results

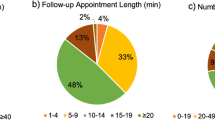

Of the 250 participants with episodic and 250 with chronic migraine, 90% were female and white with a mean age of 26.2 years (± 11.9) at diagnosis and 40.6 (± 12.0) years at survey enrollment. Many participants (71%) suspected they had migraine before diagnosis, with 31% reluctant to seek help. Of these, approximately one-third were unaware of treatment, did not think that a physician could do anything more for migraine, would not take them seriously, or were reluctant due to a previous unhelpful experience. Participants mainly received information from friends/family (47%) or the internet (28%). Participants initially sought treatment due to an increase in migraine frequency (77%), attacks interfering with work or school (75%), or increased pain intensity (74%). Subjects saw a mean of 4.1 (± 4.3) healthcare providers before migraine diagnosis, and 20% of participants previously received a different diagnosis. Participants reported migraine causes included stress/anxiety/depression (42%), hormonal changes (30%), nutrition (20%), and weather (16%). Acute treatment of migraine included prescription (82%) and over-the-counter (50%) medications, changes in nutrition (62%), adjusting fluid intake (56%), and relaxation techniques (55%). Preventive medications included anticonvulsants (61%), antidepressants (44%), blood pressure-lowering medications (43%), and botulinum toxin A injections (17%). Most discontinuations were due to lack of efficacy or side effects.

Conclusion

People with migraine describe reluctance in seeking health care, and misunderstandings seem common especially in the beginning of their migraine journey.

Graphical abstract available for this article.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Why carry out this study? |

Migraine is a prevalent, painful, and disabling neurological disorder that is under-diagnosed and under-treated. |

Recent advances have led to more effective and well-tolerated therapies preventing or reducing migraine days and improving quality of life. |

Understanding a patient’s journey from initially suspecting they have migraine to ultimately obtaining a calcitonin-gene-related-peptide (CGRP) antagonist (e.g., galcanezumab) after many years may facilitate earlier intervention. |

What was learned from the study? |

Before being diagnosed with migraine, many participants were reluctant to seek professional help for migraine for several different reasons related to their experiences with healthcare. |

Common reasons for seeking medical attention for migraine were increases in frequency of migraine attacks (77%), increases in pain severity (74%), or interference with work or school (75%). |

At the time participants received their first CGRP antagonist prescription, which could be years after diagnosis, most participants used several classes of migraine prevention medications as well as non-pharmacologic migraine management strategies. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a graphical abstract, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article, go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26569297.

Introduction

Migraine is a disease of the central nervous system characterized by episodes of intense, throbbing, mostly unilateral head pain accompanied by associated symptoms, including increased sensitivity to light or sound, and nausea and/or vomiting [1]. It inflicts a substantial effect on the quality of life of people with migraine and can cause years of suffering without adequate treatment. Migraine is among the leading worldwide causes of disability, with an economic cost measured in the billions of dollars. The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 ranks migraine as 2nd in prevalence, and among causes of disability-adjusted life-years for adults (20 to 59 years) and first for older children and adolescents (5–19 years) [4, 5]. An analysis of results from the 2019 GBD found that migraine is the leading cause of disability among women ≤ 50 years of age [2].

The patient’s journey to receive effective migraine prevention can be long, and can include barriers before and after initial diagnosis. A large proportion of people with migraine do not seek medical attention for their condition, are unaware that they are experiencing migraine, or may be misdiagnosed [3, 4]. Population-based studies have demonstrated that up to 50% of people who have symptoms of migraine have not sought medical care for it [5,6,7].

Understanding patients’ experience and how they make their decisions in seeking professional help for migraine, and the barriers they encounter in doing so could enhance patient-health care provider (HCP) interactions [8,9,10]. In this study, we have attempted to understand the prior healthcare journey in patients who were eventually prescribed an CGRP mAb (calcitonin-gene-related-peptide monoclonal antibody) by conducting a cross-sectional web survey with people with migraine who opted to enroll in the Emgality® Patient Support Program (PSP).

Methods

Design

This cross-sectional survey study was designed to evaluate the patient care journey up to initiation of their first CGRP-targeted monoclonal antibody for the treatment of migraine and did not attempt to measure the effect of galcanezumab.

Participants

Participants were recruited from the United States (US) Emgality® PSP which is a web portal administered by Eli Lilly and Company, where patients can sign up for a prescription discount card, ask questions about the medication, and access resources for additional information. At the time of recruitment, the site required participants to register with an email address and sign a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) agreement. Thus, the Emgality® PSP site was used as a resource through which potential participants either recently on galcanezumab or about to begin taking galcanezumab could be contacted.

Inclusion criteria were ≥ 18 years of age, enrolled in the US PSP, had been prescribed galcanezumab, and either had not yet started it or had used it for ≤ 6 months, had a diagnosis of migraine from their physician, self-reported at least 4 migraine days in the past month, and were able to complete informed consent and surveys in English. Exclusion criteria were self-reported diagnosis of cluster headache and prior use of another CGRP-targeted monoclonal antibody CGRP treatment.

Recruitment was stratified 1:1 by episodic migraine (EM)/chronic migraine (CM) status, defined through modified International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3) criteria as follows: patients reported varying migraine days in the month prior to study participation: EM = 4–14 monthly migraine days; CM = 15 or more monthly migraine days).

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB), Ethical & Independent Review Services (Study # 22,143-01), conformed with the International Conference on Harmonization guidelines, and was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and applicable local data protection laws. All patients provided informed consent via an electronic informed consent form.

Procedures

Pilot Test

Six participants, three with EM and three with CM at the time of the survey, were recruited from the individuals enrolled in the PSP to take part in a qualitative pilot testing phase designed to ensure appropriateness of item language (particularly for study-specific items) and to reduce survey burden. Participants engaged in a 60-min telephone or video interview with an Evidera researcher, during which they completed the survey online and then responded to questions about the survey’s duration, item order, their comprehensibility, the appropriateness of the response options, and the recall period. These data were not included in the main analysis. There was no prior relationship between these participants and the study team.

Main Study

Between March and December 2022, participants who had newly enrolled in the PSP were identified from the PSP database using weekly extractions. The contact information for potential participants was transferred from Lilly to MedPanel using a secure, limited-access, file-sharing website. All participants in the Emgality® PSP contacted for the study had previously consented to have their contact information shared with third-party vendors by Lilly, for the purpose of medical research. MedPanel invited newly enrolled (in the last week) PSP participants to the study via e-mail.

Patients interested in participating in the survey were directed to a weblink where they completed a brief eligibility screener. If patients were eligible to participate, they were asked to read and indicate their consent on an electronic informed consent form, which had to be completed before patients could access the web survey. The survey link was emailed to patients immediately upon receipt of their contact information, and the participants then completed a 20- to 30-min online survey using a HIPAA-compliant cloud-based data capture platform (Qualtrics®). Participants were permitted to skip any questions they did not wish to answer, and they could terminate the survey at will. Participants received two reminder emails over a two-week period. Participants received an Amazon gift card for US$125.

Measures

Sociodemographic Questionnaire

Participants answered questions about their age, sex at birth, height, weight, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, education, employment status, and zip code. The questionnaire aligned with the questions and response options included in the US National Health Interview Survey [11].

Self-reported Disease and Treatment-Related Questionnaire

This measure was designed to characterize the migraine care journey, including care-seeking behavior, receipt of diagnosis and treatment, and beliefs related to migraine and its treatment. Items included: age of migraine onset and diagnosis, migraine symptoms, age at diagnosis, self-reported reluctance to seek professional help, prior preventive pharmacological and nonpharmacological therapies, beliefs about causes, previous experience with health professionals related to migraine, reasons for discontinuing previous therapy, and time until galcanezumab was chosen as their first CGRP mAb. Items were developed internally and refined through the pilot testing described above. Items were analyzed separately and were not aggregated.

Analysis

The minimum recruitment of 250 participants with EM and 250 with CM was prespecified in order to provide a robust sample for mainly descriptive data analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4 software. All study variables were described. For continuous variables, N, mean, and standard deviation (SD) were calculated. Medians and range are provided for non-continuous variables. For categorical variables, N, frequency, and percentage were summarized. Only observed data were reported. Some data are missing and data from participants who completed only a portion of the survey were included in the analyses. The percentage of missing responses was reported for all variables.

Results

Participant Flow

A total of 19,088 prospective participants enrolled in the PSP between March and December 2022 were contacted. There were 2834 completed screenings, resulting in 604 who were eligible to participate (Fig. 1). The most common reason for ineligibility was sustained treatment with galcanezumab for longer than 6 months (n = 1564). Of the 604 prospective participants who met eligibility criteria, 515 provided informed consent, and 500 completed the survey (250 identified as having EM and 250 as having CM); survey completers comprised the analytic sample. Recruitment of participants was stopped after 500 surveys were completed. Missingness for most of the variables ranged from 0 to 2.7% missing, but one variable (the extent to which participants’ source of information agreed with what HCP told them) had 14% missing.

Participant Characteristics

Overall, 90% (n/N = 450/500) of participants were women, and 90% (n/N = 448/500) were White, 92% (n/N = 459/500) had at least some college education, and 73% (n/N = 366/500) were employed full time (Table 1). The mean age of participants at the time of the survey was 40.6 (± 12.0) years, and the mean time since the first migraine episode was 18.1 (± 12.7) years. The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants who later were characterized as having EM and CM at the time of the survey were similar (not shown).

The most common comorbidities reported were anxiety disorder (n/N = 25/500; 45%) and depression (n/N = 218/500; 44%) (Table 2). A migraine family history (immediate family member) was present in 59% (n/N = 295/500) of the participants. Clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Prior to Diagnosis

Overall, 71% (n/N = 357/500) of participants suspected that they had migraine before diagnosis was made. Among these participants, the most prominent sources that they relied on for information on migraine before diagnosis was advice from friends or family (n/N = 156/357; 47%) and internet search engines (n/N = 101/357; 28%). Other sources reported by participants are shown in Table 3. Participants reported either that they suspected they had migraine, or had a relative or a healthcare professional suggesting they have migraine (Table 3). Others who suggested migraine included a friend, a coworker, and teacher or school staff (Table 3).

Patient Reluctance to Seek Professional Help

There were 357 participants who suspected that they had migraine prior to diagnosis, and who were asked whether they were reluctant to seek professional help for migraine attacks. Of these, 109/375 (31%) expressed reluctance. Overall, the most common reasons that participants gave for being reluctant to seek professional help for migraine were that they did not think a physician could do anything more for their migraine attacks (n/N = 35/109; 32%), did not think the physician would take them seriously (n/N = 35/109; 32%), and that they had a previous experience with a physician that was not helpful (n/N = 35/109, 32%) (Table 3). Very few participants (n/N = 4/109; 3.7%) reported that migraines did not interfere with their daily routine.

Of those reluctant to seek professional help, 20 participants (n/N = 20/109; 18%) believed that migraine attacks were due to factors that they could control. The majority of these participants believed that they could control their migraine by changing their diet (n/N = 16/20; 80%), reducing stress levels (n/N = 14/20; 70%), using over-the-counter (OTC) medications (n/N = 13/20; 65%) or by improving their sleep routine (n/N = 13/20; 65%). Participants also felt that they could control migraines using relaxation techniques (n = 6/20; 30%), with supplements (n/N = 5; 25%), or by exercise (n/N = 4/20; 20%) (Table 3).

Seeking Professional Help for Migraine

A total of 357 participants described the factors that led them to seek professional help for migraine. The three most prominent factors, selected by > 70% of participants, were increases in headache frequency (n/N = 276/357; 77%), increases in severity (n/N = 263/357; 74%), and migraine attacks interfering with work or school (n/N = 266/357; 75%) (Table 3).

Diagnoses Other Than Migraine and Misinformation

Factors during the patient’s journey before later receiving their first CGRP-mAb for migraine prevention included their experiences in healthcare settings, beliefs about how they would be treated, beliefs about migraine triggers, and their ability to control their migraine attacks, as summarized in Table 4. Overall, the mean number of healthcare providers seen since the first migraine episode but prior to a diagnosis of migraine was 4.1 (± 4.3), with a median of 3 and a range of 1–35. Of the 500 participants, 99 (20%) reported that they initially received an alternative diagnosis prior to their migraine diagnosis. Most participants were diagnosed with migraine by a primary care or family practice physician (n/N = 256/500; 51%) or a neurologist (n/N = 178/500; 36%), as described in Table 4. The majority (> 50%) of the 99 participants who initially received an alternative diagnosis did so from a primary care or family practice physician, and 18% (n/N = 18/99) reported a different diagnosis provided by a neurologist. HCPs who provided an alternative diagnosis are shown in Table 4.

The main sources that participants reported for information on migraine changed once participants received a migraine diagnosis. After diagnosis, most participants reported getting their information from internet search engines (n/N = 208/500; 42%) or specialized or scientific publications, as interpreted by the participant (n/N = 92/500; 18%) (Table 4). Participants reported that their sources of information agreed with what their HCP told them most of the time (n/N = 232/500; 46%) or sometimes (n/N = 136/500; 27%) (Table 4).

Early Migraine Education

The three most common reasons that participants reported that HCPs had given as causing migraine were stress, anxiety, or depression (42%), hormonal changes (30%), and “don’t know” (29%), where “don’t know” means that the participant did not know the answer to the question. (Table 4).

Forty percent (n/N = 198/500) of participants reported that their HCP informed them that reducing triggers would control migraine attacks and what the participant could expect from treatment (n/N = 190/500; 38%) (Table 4). Only 28% (n/N = 142/500) of participants reported that HCPs informed them OTC pain medications did not treat the disease or prevent future attacks, rather just reduced the intensity of the current attack. They also indicated that the HCPs explained on what basis they diagnosed migraine (n/N = 142/500; 28%), explained the differences between causes and triggers (n/N = 139/500; 28%), explained that overuse of OTC pain medications could make migraine attacks worse over time (n/N = 130/500; 26%), informed them what they felt the cause of migraine could be (n/N = 75/500; 15%), and that migraine had no external cause nor was it a secondary headache (n/N = 50/500; 10%). Most participants reported that the information the HCP provided was in agreement with what they previously thought with regards to how migraine was diagnosed and the evidence leading to the diagnosis (n/N = 112/142; 79%), the difference between causes and triggers (n/N = 108/139; 78%), that reducing triggers would control migraine attacks (n/N = 161/198;81%), what the cause of migraine was (n/N = 57/75; 76%), their treatment expectations (n/N = 135/190; 71%), and that OTC pain medications may treat the attack but not prevent future attacks (n/N = 103/142; 73%). In contrast, 36% (n/N = 18/50) of participants who were told that 'migraine has no cause' reported that this was in line with what they previously thought (Table 5). There were 62 out of 130 (48%) participants who reported that being informed that overuse of OTC pain medications could make migraine attacks worse was consistent with what they previously thought (Table 5).

Acute Migraine Treatment Prior to CGRP-Targeted Monoclonal Antibody

Only eight (1.6%) participants reported never having had a pain prescription for acute treatment of migraine, either presently or in the past. Among the participants, 74% (n/N = 370/500) reported using triptans, 40% anti-nausea medications (n/N = 198/500), 39% oral CGRP antagonists (n/N = 194/500), and 15% reported using opioids (n/N = 73/500), either presently or in the past, for the acute treatment of migraine. Dihydroergotamine (n/N = 11/500; 2.2%) and lasmiditan (n/N = 4/500; 0.8%) were also reportedly used by some participants (Table 6). At the time of the survey, 82% (n/N = 409/500) reported that they were currently being prescribed at least one of these categories of pain medications for the acute treatment of migraine.

Half (n/N = 252/500; 50%) of the participants reported also taking OTC medications to treat migraine. These drugs included non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen (paracetamol), antihistamines, and decongestants.

Participants also reported using several behavioral and other non-pharmacologic methods for symptom relief during migraine attacks. These included avoiding bright lights (n/N = 435/500; 87%), rest (including sleep or relaxation; n/N = 426/500; 85%), avoiding loud noises (n/N = 394/500; 79%), and avoiding being with other people (n/N = 340/500; 68%), drinking water (n/N = 335/500; 67%), applying warm or cold compress (n/N = 287/500; 57%), eating (n/N = 104/500; 21%) (Table 6).

Preventive Migraine Treatment Prior to CGRP-Targeted Monoclonal Antibody

Participants reported using mainly four different classes of medications to prevent migraine attacks; anticonvulsants (n/N = 307/500; 61%), antidepressants (n/N = 220/500; 44%), blood pressure-lowering medications (n/N = 215/500; 43%), and botulinum toxin A (n/N = 85/500; 17%) (Table 6). The preventive medications were not mutually exclusive, and participants may have been on 2 or more medications to prevent migraine throughout their journey. Among these participants, 15% (n/N = 22/145) of those who started blood pressure lowering medications, 23% (n/N = 30/128) of those on antidepressants, 18% (n/N = 44/239) of those on anticonvulsants, and 12% (n/N = 7/57) on botulinum toxin A reported taking these preventive treatments for two or more years. A sizeable proportion of subjects reported taking anticonvulsants (n/N = 109/239; 46%), blood pressure-lowering medications (n/N = 66/145; 46%), antidepressants (n/N = 46/128; 36%), or botulinum toxin A (n/N = 15/57; 26%) for 6 or fewer months before discontinuing them.

Participants who were taking antidepressants (n/N = 94/128; 73%) or blood pressure-lowering medications (n/N = 100/145; 69%) for the prevention of migraine reported that one of the reasons that they discontinued the treatment was because it was not effective (Table 6). Some participants taking antidepressants (n/N = 57/128; 45%) or blood pressure-lowering medications (n/N = 64/145; 44%) also reported side effects as a reason for discontinuation (Table 6). In contrast, more participants taking anticonvulsants reported side effects (n/N = 168/239; 70%) over treatment not being effective (n/N = 132/239; 55%) as reasons for discontinuation (Table 6). For botulinum toxin A, treatment not being effective (n/N = 27/57; 47%) was followed by expense (n/N = 18/57; 32%) and not covered by insurance (n/N = 10/57; 18%) in order of importance as reasons for discontinuation (Table 6). Reasons participants expressed for discontinuation of a drug class were not mutually exclusive, and they could indicate more than one reason for each drug class.

The participants also reported trying a variety of non-pharmacological methods to prevent their migraine attacks. The most common (> 50%) were changes in nutrition, adjusting fluid intake, and relaxation techniques (Table 6).

Discussion

In general, participants suspected that they had migraine before receiving a diagnosis from an HCP. Reasons given by participants who expressed a reluctance to seek professional help included previous experiences that were not helpful, or concern that they would not be taken seriously. Impediments receiving adequate care included possible misinformation and initially receiving alternative diagnoses than migraine. Some participants revealed they had visited several HCPs before knowing for sure they had migraine, and many cycled through different treatment modalities. This study sets the stage for future research aiming to better understand how people realize they have migraine, what hinders or motivates information- and treatment-seeking, and how initial treatment modality decisions are made.

Most participants reported they suspected having migraine prior to their diagnosis, suggesting that general awareness about the disease was high. The main sources of information on migraine were advice or examples from family and friends and internet searches, while seeking information from their HCP was less common. This indicates that a greater proportion of people with migraine may be receiving migraine-related information from less reliable sources, at least initially, which could perpetuate misconceptions about causes and treatments and thus highlights the need for public health education about migraine through trusted sources.

Among participants who suspected that they had migraine prior to diagnosis, approximately one-third (31%) expressed reluctance in seeking professional help. In line with this finding, the recent ObserVational survey of the Epidemiology, tReatment and Care Of MigrainE (OVERCOME) (US) study (n = 21,143 people with migraine), revealed that only 51% sought care within the previous 12 months [7]. In the present study, we found that the reluctance was more pronounced among those who later were categorized as having CM than those with EM, which is also consistent with results from the OVERCOME study [7]. These observations might seem counterintuitive, as people with more severe or frequent headaches would be expected to have more fear of a life threatening disease, such as a tumor or aneurism, and therefore seek treatment more frequently [12,13,14].

Our study did not directly address stigma, though two common responses for reluctance in seeking professional help were that subjects had unhelpful previous interactions with physicians and feared that they would not be taken seriously. The OVERCOME study assessed the effect of migraine stigma including the impact on treatment seeking behavior in US subjects and found that approximately one-third with often/very often stigma experience, had more disability, greater interictal burden, and reduced quality of life [15].

Participants reported migraine misconceptions that could contribute to a reluctance to seek professional help [16]. More than half of participants believed that improving their diet or sleep routine, or the use of OTC pain medications, could control the disease. This may be attributed to mild or infrequent migraine, but also to a misunderstanding about the disease, its mechanisms, and consequently appropriate treatment. Patients overusing acute medications (either OTC or prescription) to treat migraine risk potentially worsening their condition by developing medication overuse headache [17]. These misconceptions could arise in part due to the sources of information, as most indicated that their primary source was advice from family and friends or internet sources.

Multiple factors were identified as instigators of care-seeking, including increasing headache attack frequency or severity, interference with work or school, and persistence of migraine despite taking medications. However, once the decision to seek professional help was made, it did not always lead to a prompt diagnosis and treatment. Often, participants reported receiving a diagnosis other than migraine, and, on average, they saw 4 HCPs before being properly diagnosed. In the present study, one of the participants who reported that they initially received a diagnosis other than migraine had seen as many as 35 HCPs before receiving a migraine diagnosis. Most HCPs involved in diagnosing migraine were PCPs followed by neurologists.

Reasons for reluctance to seek treatment could be related to misleading communications about the nature of migraine [9, 10, 18]. It is important for patients with migraine to understand that a cause of migraine explains why they have migraine disorder, whereas triggers explain the reasons that might precipitate a migraine episode. Participants reported a misconception between the “cause” of migraine (e.g., why one has migraine disease), and triggers of individual migraine attacks (e.g., putative precipitating factors for an individual migraine attack, which occurs in an individual who has migraine disease). Over 80% of participants described these beliefs as consistent with how their HCP described the cause of migraine. Approximately 65% of participants reported the explanation that migraine has no cause (e.g., that migraine is a primary headache disorder) was contrary to their prior beliefs. Migraine causes as reported by participants from what they understood from their physicians included dental issues, sinus and visual disorders or allergies. Migraine is a primary headache disorder, as opposed to secondary headache disorders caused by other factors; unfortunately, confusion between migraine, “sinus headache”, and allergy is common [19,20,21]. Results from the present study suggest that current norms regarding migraine education in healthcare settings could be strengthening misconceptions that migraine is a headache disorder secondary to other causes. Future research should utilize a structured approach to evaluation and education of headache patients [22] using the Common Sense Model of Illness [23], which provides a framework for moving patients from “lay beliefs” about a disease (e.g., migraine is “caused” by allergies) to “expert beliefs” about a disease; attacks may have many precipitants, including allergic reactions. Although the majority of patients reported receiving prescriptions for acute treatment, more than half of the patients indicated following non-pharmacologic modalities such as relaxation techniques and adjusting fluid intake, which may be lacking evidence of effect.

Traditional oral migraine preventive medications not specifically developed for migraine have been available for years, and indeed helped many patients as alternatives to no treatment. However, the current study found that inefficacy and side effects were the most common reasons for discontinuation of other preventive treatment options trialed before initiating an CGRP mAb, and being persistent on migraine preventives is associated with better treatment outcomes. Across all medication classes, the majority of participants reported being on the medication for more than 6 months before discontinuing. Delays in access to treatments effective for the individual person with migraine lead to additional months to years of disease burden. A recent observational retrospective Spanish cohort study assessing > 7850 electronic medical records (the PERSEC study) compared healthcare resource utilization and cost between those who were persistently on traditional oral migraine preventive medication for ≥ 1 year versus those who were not [24]. Non-persistent patients required a higher number of primary care visits, days of sick leave, and annual expenditure versus the persistent ones [24]. An online survey of patients who currently have, or previously had, high-frequency episodic migraine (≥ 8 days with headache per month) and acute medication overuse (≥ 10 days per month of any acute migraine or headache medication) showed that the use of preventive medications was low in both groups of patients; the authors concluded that optimizing treatment (in terms of efficacy, tolerability, adherence) is important in preventing progression to increased headache frequency and medication overuse [25]. An observational retrospective cohort study using data from a tertiary headache center found that low adherence to traditional (i.e. antidepressants, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and anti-epileptic drugs) oral preventive treatments is often attributed to low efficacy over time and/or intolerability of side-effects [26]. It was suggested that trials with different oral preventives delayed the use of new therapies, such as the CGRP mAbs [26]. The first CGRP mAbs were regulatory approved in 2018 and the higher cost has historically restricted their use until other preventative treatments for migraine had been tried. Recent cost–benefit analyses regarding early employment of the CGRP mAbs in Spain and Germany both suggested that the higher cost of the treatment is mitigated by the improvement in patients’ condition [27,28,29]. Savings in both direct (e.g., acute medication use, hospital visits) and indirect (e.g., absenteeism/presenteeism, disability) costs can potentially be realized by early implementation of CGRP mAb therapy [27,28,29]. In fact, a recent 1-year US claims study reported significant cost savings in mean acute and preventive migraine prescription costs with CGRP mAbs compared to standard of care (SOC) [30]. Another recent retrospective study using 2-year insurance claims data conducted in the United States found that the pharmacy cost of treatment with galcanezumab was greater when compared to traditional SOC migraine preventive medications, although patients on galcanezumab had lower all-cause and migraine-related office visits over the 24-month follow-up. Indirect cost was not assessed [31]. The same study found that patients who initiated galcanezumab for migraine prevention had higher treatment adherence and persistence compared with those who initiated SOC medications after 24-month follow-up [32].

The latest updated European Headache Federation guidelines (2022) now recommend the use of CGRP mAbs as a first-line treatment option in people with migraine who require preventive treatment [33], due to superior efficacy and tolerability compared to alternatives [34,35,36,37]. Until recently, the American Headache Society (AHS) consensus statement [38] as well as US payor formularies required inadequate response or inability to tolerate at least 2 classes of other migraine preventive treatments. However, the AHS also recently (February 2024) updated their position statement to state that therapies that target CGRP should be considered first-line therapies for migraine prevention without a requirement for earlier failures with other classes of therapies [39].

Limitations

In this study, men and ethnic minorities are under-represented, beyond the higher migraine prevalence found in women [40,41,42,43]. Future studies should assess if both groups face additional barriers to diagnosis and access to effective treatments [44,45,46]. Participants in the current study were sufficiently motivated by their disease characteristics and burden that they eventually chose to initiate treatment with a CGRP mAb; patients with less severe disease burden likely have different experiences in their care pathways. Participants were selected from the PSP program, which required enrolment in a private health insurance plan; consequently, the care journey of patients who have no insurance or who are on government-sponsored plans such as Medicare or Medicaid was not captured here. The current study utilized survey research, which permits quantifying variables; future studies should consider utilizing qualitative research to better understand the care journey of patients with migraine, particularly as it relates to beliefs and barriers to accessing care. Patients in the current study were retrospectively recalling experiences with their initial diagnosis and treatments up to the current time, introducing a potential for recall bias as some of these experiences occurred months, or even in some cases years, in the past. Future prospective studies should proactively recruit patients prior to initial diagnosis, and immediately after initial diagnosis, to gain more insight into this critical timepoint in the migraine treatment journey.

Conclusions

The journey of patients with migraine, from the time they realize that their symptoms are consistent with a migraine diagnosis, until they receive treatment with CGRP mAb, can be lengthy and convoluted. Patients may be working under a “lay model” of disease that mischaracterizes the disease as secondary to other clinical phenomenon, or a stigmatizing model that blames patients for their symptoms or indicates the symptoms are not a “big deal” and can be managed with only lifestyle change and OTC medications. Patients may be reluctant to seek professional help due to these beliefs, and to other social, economic, and systemic reasons. Patients seeking professional help is a decision. This decision is influenced by their personal beliefs, their social context, their economic context, and their past experiences, particularly with the healthcare system. Cycling through multiple acute and preventive treatments can delay the journey of a patient who would benefit from CGRP mAbs for the treatment of migraine. Increased awareness of patients’ journeys to treatment, and concerted evidence-based efforts to address barriers along this journey, could improve migraine care.

Data Availability

Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the US and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.

References

International Headache Society. IHS Classification ICHD-3: Migraine. 2021. https://ichd-3.org/1-migraine/. Accessed Apr 2022.

Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Jensen R, Uluduz D, Katsarava Z, on behalf of Lifting The Burden: the Global Campaign against H. Migraine remains second among the world’s causes of disability, and first among young women: findings from GBD2019. J Headache Pain. 2020;21(1):137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-01208-0.

Lipton RB, Munjal S, Alam A, Buse DC, Fanning KM, Reed ML, et al. Migraine in America Symptoms and Treatment (MAST) study: baseline study methods, treatment patterns, and gender differences. Headache. 2018;58(9):1408–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13407.

Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, Dodick DW, Argoff C, Ashman E, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78(17):1337–45. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182535d20.

Dodick DW, Loder EW, Manack Adams A, Buse DC, Fanning KM, Reed ML, Lipton RB. Assessing barriers to chronic migraine consultation, diagnosis, and treatment: results from the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) study. Headache. 2016;56(5):821–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12774.

Lipton RB, Buse DC, Serrano D, Holland S, Reed ML. Examination of unmet treatment needs among persons with episodic migraine: results of the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Headache. 2013;53(8):1300–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12154.

Lipton RB, Nicholson RA, Reed ML, Araujo Andre B, Jaffe DH, Faries DE, et al. Diagnosis, consultation, treatment, and impact of migraine in the US: Results of the OVERCOME (US) study. Headache J Head Face Pain. 2022;62(2):122–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14259.

Bingel U. Placebo 2.0: the impact of expectations on analgesic treatment outcome. Pain. 2020;161(Suppl 1):S48–56. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001981.

Laferton JA, Kube T, Salzmann S, Auer CJ, Shedden-Mora MC. Patients’ expectations regarding medical treatment: a critical review of concepts and their assessment. Front Psychol. 2017;8:233. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00233.

Schmidt K, Berding T, Kleine-Borgmann J, Engler H, Holle-Lee D, Gaul C, Bingel U. The beneficial effect of positive treatment expectations on pharmacological migraine prophylaxis. Pain. 2022;163(2):e319–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002341.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health Interview Survey. Cited from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm. 2023.

Abrams BM. Factors that cause concern. Med Clin North Am. 2013;97(2):225–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2012.11.002.

Eller M, Goadsby PJ. MRI in headache. Expert Rev Neurother. 2013;13(3):263–73. https://doi.org/10.1586/ern.13.24.

Green MW, Green LM. Are you sure i don’t have a brain tumor? In: Managing your headaches. New York, NY: Springer; 2001. p. 33–45.

Shapiro RE, Nicholson RA, Seng EK, Buse DC, Reed ML, Zagar AJ, et al. Migraine-related stigma and its relationship to disability, interictal burden, and quality of life: results of the OVERCOME (US) study. Neurology. 2024;102(3): e208074. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000208074.

Wenzel R, Dortch M, Cady R, Lofland JH, Diamond S. Migraine headache misconceptions: barriers to effective care. Pharmacotherapy. 2004;24(5):638–48. https://doi.org/10.1592/phco.24.6.638.34751.

Diener HC, Holle D, Solbach K, Gaul C. Medication-overuse headache: risk factors, pathophysiology and management. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(10):575–83. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2016.124.

Patrick DL, Martin ML, Bushnell DM, Pesa J. Measuring satisfaction with migraine treatment: expectations, importance, outcomes, and global ratings. Clin Ther. 2003;25(11):2920–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80345-4.

Tepper SJ. New thoughts on sinus headache. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2004;25(2):95–6.

Robblee J, Secora KA. Debunking myths: sinus headache. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2021;21(8):42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-021-01127-w.

Eross E, Dodick D, Eross M. The Sinus, Allergy and Migraine Study (SAMS). Headache. 2007;47(2):213–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00688.x.

Cady RK. Red flags and comfort signs for ominous secondary headaches. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2014;47(2):289–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2013.10.010.

Leventhal H, Brissette I, Leventhal EA. The common-sense model of self-regulation of health and illness. In: The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour. New York, NY, US: Routledge; 2003. p. 42–65.

Irimia P, García-Azorín D, Núñez M, Díaz-Cerezo S, de Polavieja PG, Panni T, et al. Persistence, use of resources and costs in patients under migraine preventive treatment: the PERSEC study. J Headache Pain. 2022;23(1):78. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-022-01448-2.

Starling AJ, Cady R, Buse DC, Buzby M, Spinale C, Steinberg K, et al. Harris poll migraine report card: population-based examination of high-frequency headache/migraine and acute medication overuse. J Headache Pain. 2024;25(1):26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-024-01725-2.

Delussi M, Vecchio E, Libro G, Quitadamo S, de Tommaso M. Failure of preventive treatments in migraine: an observational retrospective study in a tertiary headache center. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):256. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-020-01839-5.

Hong JB, Lange KS, Fitzek M, Overeem LH, Triller P, Siebert A, et al. Impact of a reimbursement policy change on treatment with erenumab in migraine: a real-world experience from Germany. J Headache Pain. 2023;24(1):144. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-023-01682-2.

Lazaro-Hernandez C, Caronna E, Rosell-Mirmi J, Gallardo VJ, Alpuente A, Torres-Ferrus M, Pozo-Rosich P. Early and annual projected savings from anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies in migraine prevention: a cost-benefit analysis in the working-age population. J Headache Pain. 2024;25(1):21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-024-01727-0.

Schoenen J, Van Dycke A, Versijpt J, Paemeleire K. Ten open questions in migraine prophylaxis with monoclonal antibodies blocking the calcitonin-gene related peptide pathway: a narrative review. J Headache Pain. 2023;24(1):99. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-023-01637-7.

Varnado OJ, Manjelievskaia J, Ye W, Perry A, Schuh K, Wenzel R. Health care resource utilization and costs associated with treatment among patients initiating calcitonin gene–related peptide inhibitors vs other preventive migraine treatments in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28(8):818–29. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2022.28.8.818.

Varnado OJ, Vu M, Buysman E, Kim G, Allenback G, Hoyt M, et al. Healthcare resource utilization and direct costs incurred over 24 months after initiating galcanezumab or standard-of-care preventive migraine treatments in the United States. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy (2024, in press).

Varnado OJ, Vu M, Buysman EK, Kim G, Allenback G, Hoyt M, et al. Treatment patterns of galcanezumab versus standard of care preventive migraine medications over 24 months: a US retrospective claims study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2024;40(4):635–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2024.2316864.

Sacco S, Amin FM, Ashina M, Bendtsen L, Deligianni CI, Gil-Gouveia R, et al. European Headache Federation guideline on the use of monoclonal antibodies targeting the calcitonin gene related peptide pathway for migraine prevention – 2022 update. J Headache Pain. 2022;23(1):67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-022-01431-x.

Blumenfeld AM, Bloudek LM, Becker WJ, Buse DC, Varon SF, Maglinte GA, et al. Patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation of prophylactic medications for episodic migraine and chronic migraine: results from the second international burden of migraine study (IBMS-II). Headache. 2013;53(4):644–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12055.

Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, Chia J, Matthew N, Gillard P, et al. Persistence and switching patterns of oral migraine prophylactic medications among patients with chronic migraine: a retrospective claims analysis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(5):470–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102416678382.

Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, Gillard P, Hansen RN, Devine EB. Adherence to oral migraine-preventive medications among patients with chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(6):478–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102414547138.

Blumenfeld AM, Varon SF, Wilcox TK, Buse DC, Kawata AK, Manack A, et al. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia. 2011;31(3):301–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102410381145.

Ailani J, Burch RC, Robbins MS, Society tBoDotAH. The American Headache Society Consensus Statement: Update on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache: J Head Face Pain. 2021;61(7):1021–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14153.

Charles AC, Digre KB, Goadsby PJ, Robbins MS, Hershey A, Society TAH. Calcitonin gene-related peptide-targeting therapies are a first-line option for the prevention of migraine: an American Headache Society position statement update. Headache: J Head Face Pain. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14692.

GBD 2016 Headache Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(11):954–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30322-3.

Goadsby PJ, Holland PR, Martins-Oliveira M, Hoffmann J, Schankin C, Akerman S. Pathophysiology of migraine: a disorder of sensory processing. Physiol Rev. 2017;97(2):553–622. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00034.2015.

Amiri P, Kazeminasab S, Nejadghaderi SA, Mohammadinasab R, Pourfathi H, Araj-Khodaei M, et al. Migraine: a review on its history, global epidemiology, risk factors, and comorbidities. Front Neurol. 2021;12: 800605. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.800605.

Piccininni M, Brinks R, Rohmann JL, Kurth T. Estimation of migraine prevalence considering active and inactive states across different age groups. J Headache Pain. 2023;24(1):83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-023-01624-y.

Lt C, Spears RC, Flippen C 2nd. Equity of African American Men in headache in the United States: a perspective from African American headache medicine specialists (part 1). Headache. 2020;60(10):2473–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14004.

Perez MA, Reyes-Esteves S, Mendizabal A. Racial and ethnic disparities in neurological care in the United States. Semin Neurol. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1778639.

Scher AI, Wang SJ, Katsarava Z, Buse DC, Fanning KM, Adams AM, Lipton RB. Epidemiology of migraine in men: results from the Chronic Migraine Epidemiology and Outcomes (CaMEO) study. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(2):296–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102418786266.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants for taking part in this survey. The authors also thank Virginia S. Haynes, PhD, of Eli Lilly and company for help with the study design and developing the protocol.

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance. Eli Lilly and Company contracted Evidera-PPD to help design, conduct, analyze, and report on the study and for writing and/or editorial services. Editorial assistance in the preparation of this article was provided by Dr. Surayya Taranum of Evidera for editorial assistance.

Authorship. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have provided their approval for this version to be published.

Funding

This work was funded by Eli Lilly and Company. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception/design: Maurice Vincent, Lars Viktrup, William R. Lenderking, Hayley Karn, Margaret Hoyt, Gilwan Kim. Drafting and/or critical revision of paper for important intellectual content: All authors (Elizabeth Seng, Christian Lampl, Lars Viktrup, William R. Lenderking, Hayley Karn, Margaret Hoyt, Gilwan Kim, Dustin Ruff, Michael H. Ossipov, Maurice Vincent). Approval of final version of the paper: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Elizabeth Seng: research funding from the National Institutes of Health, Veterans Health Administration, Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, and the American Heart Association, as well as fees for consulting from GlaxoSmithKline, Theranica, and Abbvie. Christian Lampl: consulting fees and honoraria for lectures/ presentations from AbbVie/Allergan, Eli Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis, Pfizer and Teva. Principal investigator in clinical trials as the for Eli Lilly. Past-president of the European Headache Federation and associate editor for The Journal of Headache and Pain. Lars Viktrup, Margaret Hoyt, Gilwan Kim,, and Dustin Ruff are employees of Eli Lilly and Company and may own Lilly stock. Maurice Vincent was an employee of Eli Lilly and Company when the study was performed and may own Lilly stock. William R. Lenderking, Hayley Karn, Michael H. Ossipov are employees of Evidera.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the IRB Ethical & Independent Review Services (Study # 22143-01) and conformed with International Conference on Harmonization guidelines and was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and applicable local data protection laws. All patients provided informed consent via an electronic informed consent form.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Seng, E., Lampl, C., Viktrup, L. et al. Patients’ Experiences During the Long Journey Before Initiating Migraine Prevention with a Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) Monoclonal Antibody (mAb). Pain Ther (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-024-00652-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-024-00652-z