Abstract

Introduction

Brain and spinal cord injuries may cause very severe spasticity that occasionally may be associated with persistent fever.

Case Series

We present 14 patients with spasticity and persistent fever, treated with botulinum toxin type A. Their spasticity improved and the fever resolved within a period no greater than 48 h. In all cases, infectious and other non-infectious causes were ruled out.

Conclusions

When sustained tonic muscular activity is associated with a significant increase in body temperature and is refractory to the usual drugs used for hyperpyrexia, type A botulinum toxin may be an effective treatment option to control both spasticity and fever.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The hypothalamus is the regulatory center for body temperature in humans [1], although the diencephalon and spinal cord also contribute [2]. If one of these structures is damaged, temperature elevations above 38.3 °C can occur [3].

Temperature elevations of brain origin are associated with increased plasmatic levels of norepinephrine and dopamine-B-hydroxylase [4]. In fever of spinal cord origin, the amplification of its positive feedback mechanism can induce and increase sympathetic responses [5]. Fever in patients with brain damage is associated with increased mortality [6, 7]; in cases with spasticity, this is a diagnosis of exclusion, and other causes of fever, such as infectious or non-infectious, must be ruled out [8]. Thus, prompt diagnosis of the cause and appropriate treatment are needed.

The production of body heat and fever results from the interaction of various factors, such as cellular metabolism, hormonal regulation, increased metabolism due to catecholamines such as epinephrine and norepinephrine [1], and muscular activity [2]. Muscular activity is a major factor in the production of heat under physiological conditions [1, 2].

On the other hand, spasticity is commonly described as a motor dysfunction in which there is increased muscular tone with an augmented stretch reflex [9]. Spasticity can be severe in patients with brain injury (BI) or spinal cord injury (SCI) [10]. There are various pharmacological treatments for spasticity [2], but botulinum neurotoxin type A (BoNTA) is among the most efficient and safe treatments for this condition [11].

Sustained states of muscle contraction have been reported to cause fever [2, 12,13,14]. To our knowledge, fever has not been described as a symptom associated with spasticity. Here, we present 14 patients with BI or SCI with severe spasticity who also had refractory fever without an infectious etiology.

Methods

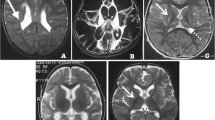

We report 14 cases treated between July 10, 2010, and December 16, 2016, who had BI or SCI with severe spasticity and refractory fever. Infectious and non-infectious causes of fever were ruled out with cultures and with laboratory and imaging studies.

This project was presented to the ethics and research committee of our hospital and was approved.

Results

The patients included six women (42.86%) and eight men (57.14%) aged 21 to 81 years (mean 45.71 years). The cause of the persistent and refractory muscular contraction was closed head injury in four patients (28.58%), hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy in three (21.43%), cervical SCI in three (21.43%), hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage in one (7.14%), subarachnoid hemorrhage in one (7.14%), intracerebral hemorrhage secondary to complications of carotid artery stent placement in one (7.14%), and stroke due to thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in one (7.14%).

Spasticity was measured using the modified Ashworth spasticity scale [15], and we found severe spasticity in four limbs of eight patients (57.14%) and hemibody spasticity in three patients (21.43%) and in the upper limbs of two subjects (21.43%). All patients were treated for their spasticity with BoNTA; 11 patients (78.57%) received onabotulinumtoxinA, and three (21.43%) received abobotulinumtoxinA.

All patients exhibited improvement of their spasticity. Before treatment with BoNTA, 11 patients (78.57%) had a score of 5, and three (21.43%) patients had a score of 4. At a 2-month follow-up examination, four patients (28.58%) improved to a score of 4, six patients (42.86%) to a score of 3, and four patients (28.58%) to a score of 2 (Table 1).

To our surprise, fever resolved in all patients (100%) in a period no greater than 48 h; at the 2-month follow-up, no recurrence was observed.

Discussion

The patients described in this report had some form of BI or SCI, and as a consequence of this damage, they developed spasticity with concurrent temperature elevation. In all cases, infectious, inflammatory etiology was ruled out.

The treatment of fever in general should be specific for the etiology whenever possible and not just targeted toward the symptom [1]. Similar to reports by other authors, all patients received treatment with antipyretics, muscle relaxants and physical methods without an adequate control [16].

In all cases, there was improvement of spasticity after application of BoNTA, which facilitated neurorehabilitation. Fever resolved in no more than 48 h without any recurrence. Application of BoNTA is an accepted treatment for spasticity [2, 15, 16], and to our knowledge, BoNTA has not been reported for the treatment of fever in patients with spasticity.

There are other pathological entities, such as exertional heat stroke (EHS) [13] and malignant hyperthermia (MH), in which a disorder of calcium homeostasis within muscle cells causes muscle contraction [12]. MH was first described as a rare complication of general anesthesia [17] but has also been reported in a head injury patient as well as in one with SCI [18, 19].

Even though in most cases with spasticity there is no fever associated with sustained muscle contraction, there is a persistent increase in the free myoplasmic calcium concentration, producing a biochemical reaction that accelerates mitochondrial activity with an increase in oxygen consumption. MH is associated with elevation of the production of carbon dioxide that depletes aerobic metabolism and increases anaerobic metabolism, leading to an imbalance of intracellular and extracellular ionic interchange that results in damage to the myocytes [12, 20]. The interruption of the active transport across the cell membrane consumes energy due to the high exchange of adenosine triphosphate (ATP); this exchange may be responsible for the temperature elevation in EHS [13] and MH [21]. There are also situations where other states of sustained muscular activity, such as dopaminergic withdrawal malignant syndrome, which is associated with rigidity, can cause fever regardless of whether they cause muscle damage [14]. To our knowledge, there are no reports of fever associated with spasticity.

Sustained muscle contraction has been considered as a cause of hyperpyrexia [1]. This complication first appears in the intensive care setting but may persist for months [22].

MH is treated with dantrolene, which inhibits the release of calcium from the sarcoplasmic reticulum with muscle relaxant action. Importantly, dantrolene does not have any action on the neuromuscular junction [23], but BoNTA does [24]. BoNTA acts as a metalloproteinase with a peripheral cholinergic effect on nerve endings; this effect causes reversible inhibition of presynaptic acetylcholine (Ach) [24] release without motor neuron loss [25]. After BoNTA is applied directly into the muscle, it passes through the endosomal membrane and causes a reversible but persistent inhibition of neurotransmitter release due to intracellular endopeptidase activity against the proteins necessary for Ach release [25]. How spasticity potentially causes fever is unclear. We hypothesize that, if the muscle contraction is the cause of fever, BoNTA could reduce the energy imbalance of ATP in myocytes caused by severe spasticity and directly decrease body temperature. However, we cannot rule out other sites of action for BoNTA.

BoNTA may be a good treatment alternative for refractory fever in patients with spasticity.

The limitations of our paper are the lack of a control group, because this is a case series report, since we know that the majority of patients with spasticity do not develop a fever.

More studies should be done in patients with similar characteristics and should emphasize the causes of fever, as well as how BoNTA decreases body temperature in these subjects. This finding may also be extended to cases of dystonia and rigidity.

References

Sneed RC. Hyperpyrexia associated with sustained muscle contractions: an alternative diagnosis to central fever. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76:101–3.

Mandac BR, Hurvitz EA, Nelson VS. Hyperthermia associated with baclofen withdrawal and increased spasticity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993;74:96–7.

Petersdorf RG, Beeson PB. Fever of unexplained origin: report on 100 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1961;40:1–30.

Clifton GL, Ziegler MG, Grossman RG. Circulating catecholamines and sympathetic activity after head injury. Neurosurgery. 1981;8:10–4.

Lump D, Moyer M. Paroxysmal sympathetic hyperactivity after severe brain injury. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2014;14:494.

Saxena M, Young P, Pilcher D. Early temperature and mortality in critically ill patients with acute neurological diseases: trauma and stroke differ from infection. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:823–32.

Greer DM, Funk SE, Reaven NL, Ouzounelli M, Uman GC. Impact of fever on outcome in patients with stroke and neurologic injury: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Stroke. 2008;39:3029–35.

Heiman-Patterson TD. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and malignant hyperthermia. Important issues for the medical consultant. Med Clin North Am. 1993;77:477–92.

Lance JW. The control of muscle tone, reflexes, and movement: Robert Wartenberg Lecture. Neurology. 1980;30:1303–13.

Dressler D, Bhidayasiri R, Bohlega S, Chahidi A, Chung TM, Ebke M, et al. Botulinum toxin therapy for treatment of spasticity in multiple sclerosis: review and recommendations of the IAB-interdisciplinary working group for movement disorders task force. J Neurol. 2017;264:112–20.

Dressler D. Clinical applications of botulinum toxin. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2012;15:325–36.

MacLennan DH, Phillips MS. Malignant hyperthermia. Science. 1992;256:789–94.

Zhao X, Song Q, Gao Y. Hypothesis: exertional heat stroke-induced myopathy and genetically inherited malignant hyperthermia represent the same disorder, the human stress syndrome. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2014;70:1325–9.

Howard ZD, Rempell JS, Nadel ES, Brown DFM. Fever and rigidity. J Emerg Med. 2011;40:668–70.

Bohannon RW, Smith MB. Interrater reliability of a modified ashworth scale of muscle spasticity. Phys Ther. 1987;67:206–7.

Pérez-Arredondo A, Cázares-Ramírez E, Carrillo-Mora P, Martínez-Vargas M, Cárdenas-Rodríguez N, Coballase-Urrutia E, et al. Baclofen in the therapeutic of sequele of traumatic brain injury: spasticity. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2016;39:311–9.

Denborough MA, Forster JFA, Lovell RR, Maplestone PA, Villiers JD. Anaesthetic deaths in a family. Br J Anaesth. 1962;34:395–6.

Feuerman T, Gade GF, Reynolds R. Stress-induced malignant hyperthermia in a head-injured patient. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:297–9.

Steele SR, Martin MJ, Mullenix PS, Long WB, Gubler KD. Fatal malignant hyperpyrexia in a cervical spine- injured patient. J Trauma. 2005;58:375–7.

Wappler F, Fiege M, Steinfath M, Agarwal K, Scholz J, Singh S, et al. Evidence for susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia in patients with exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. Anesthesiology. 2001;94:95–100.

MacLennan DH. Ca2+ signalling and muscle disease. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:5291–7.

Blackman JA, Patrick PD, Buck ML, Rust RS Jr. Paroxysmal autonomic instability with dystonia after brain injury. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:321–8.

Harrison GG. Malignant hyperthermia. Dantrolene-dynamics and kinetics. Br J Anaesth. 1988;60:279–86.

Wenham T, Cohen A. Botulism. Contin Educ Anaesth Crit Care Pain. 2008;8:21–5.

de Paiva A, Meunier FA, Molgó J, Aoki KR, Dolly JO. Functional repair of motor endplates after botulinum neurotoxin type A poisoning: biphasic switch of synaptic activity between nerve sprouts and their parent terminals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3200–5.

Acknowledgements

Centro de Neurorehabilitación Angeles. Presented as a poster in the XLII Annual Congress of the Mexican Association of Infectology and Clinical Microbiology. Puebla, Puebla, Mexico. May 24-27, 2017.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The article processing charges were funded by the authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Jacobo Lester, Gerardo Esteban Alvarez-Resendiz, Enrique Klériga, Fernando Videgaray and Gerardo Zambito have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The project was presented to the ethics and research committee of our hospital and was approved.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. We confirm that Table 1 is original and was produced by the authors for this particular publication.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/A12DF0601FC379C1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lester, J., Alvarez-Resendiz, G.E., Klériga, E. et al. Treatment with Botulinum Toxin for Refractory Fever Caused by Severe Spasticity: A Case Series. Neurol Ther 7, 155–159 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-018-0092-1

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-018-0092-1