Abstract

Objective

Vaccination is the most efficient way to control the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, but vaccination rates remain below the target level in most countries. This multicenter study aimed to evaluate the vaccination status of hospitalized patients and compare two different booster vaccine protocols.

Setting

Inoculation in Turkey began in mid-January 2021. Sinovac was the only available vaccine until April 2021, when BioNTech was added. At the beginning of July 2021, the government offered a third booster dose to healthcare workers and people aged > 50 years who had received the two doses of Sinovac. Of the participants who received a booster, most chose BioNTech as the third dose.

Methods

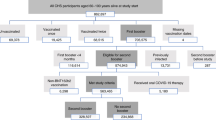

We collected data from 25 hospitals in 16 cities. Patients hospitalized between August 1 and 10, 2021, were included and categorized into eight groups according to their vaccination status.

Results

We identified 1401 patients, of which 529 (37.7%) were admitted to intensive care units. Nearly half (47.8%) of the patients were not vaccinated, and those with two doses of Sinovac formed the second largest group (32.9%). Hospitalizations were lower in the group which received 2 doses of Sinovac and a booster dose of BioNTech than in the group which received 3 doses of Sinovac.

Conclusion

Effective vaccinations decreased COVID-19-related hospitalizations. The efficacy after two doses of Sinovac may decrease over time; however, it may be enhanced by adding a booster dose. Moreover, unvaccinated patients may be persuaded to undergo vaccination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), rapidly developed into a pandemic with approximately 210 million cases of infection and more than 4.4 million deaths recorded worldwide as of August 19, 2021 [1]. The rapid and successful development of COVID-19 vaccines is a significant hallmark of this pandemic [2, 3]. Vaccination is the most efficient way to control the pandemic; however, vaccination rates are still below the targeted level in most countries [4], and cases continue to increase despite the existence of effective vaccines. The anti-vaccine movement and vaccine hesitancy are prominent issues. There are different types of vaccines, including mRNA, vector, and inactivated vaccines, and population studies have documented their success [5,6,7,8,9]. Vaccine supply, vaccine combinations, booster doses, and new virus variants are controversial matters. Turkey is one of the most affected countries and is currently experiencing the fourth wave of the pandemic. In general, vaccination programs are considered successful (> 72% of the adult population have received their first dose) [10] despite anti-vaccine campaigns and vaccine hesitancy. Turkey is the first country to offer two options for a third (booster) dose to its residents. This multicenter study aimed to evaluate the vaccination status of hospitalized patients and compare the efficacy of the two booster vaccine protocols.

Methods

We collected data from 25 hospitals in 16 cities. Patients hospitalized between August 1 and 10, 2021, were included. Patients hospitalized because of social indications for isolation were excluded.

Age, sex, vaccination status, comorbidities (such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, chronic lung disease, cerebrovascular disease, cancer, and chronic kidney disease), and the reason for the patients not being vaccinated (if available) were collected. The patients were categorized into two groups based on whether they were admitted to the intensive care unit or were treated in clinics. A government vaccine tracking system was used to determine the patients' vaccination status and vaccination dates. There are two types of vaccines available in Turkey: Sinovac (inactivated virus) and BioNTech (mRNA).

The patients were categorized into eight groups according to their vaccination status:

0: Unvaccinated,

1: Two doses of Sinovac,

2: Two doses of BioNTech,

3: Three doses of Sinovac,

4: Two doses of Sinovac + one dose of BioNTech,

5: One dose of Sinovac,

6: One dose of BioNTech,

7: Two to three doses of Sinovac with or without BioNTech, but less than 14 days after the last dose;

The reasons for not getting vaccinated are questioned, such as negligence, hesitancy, or anti-vaccine advocacy.

We also obtained data from the Ministry of Health website [11]. The study was approved by the Ministry of Health, and the Turkish Thoracic Society supported the study.

Student t and chi-square tests were used for statistical analysis, and a p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

We enrolled 1401 patients (715 men, 686 women; mean age 59.7 years) from the hospitals, of which 529 (37.7%) were admitted to intensive care units. Approximately half (47.8%) of the patients were unvaccinated, and the next largest group comprised those who received two doses of Sinovac (32.9%). Vaccination status, sex, mean age, and the number of patients' comorbidities are presented in Table 1.

Vaccination status

0: not vaccinated, 1: two doses of Sinovac, 2: two doses of BioNTech, 3: three doses of Sinovac, 4: two doses of Sinovac + one dose of BioNTech, 5: one dose of Sinovac, 6: one dose of BioNTech, 7: two doses of Sinovac with or without BioNTech, but less than 14 days after the last dose.

Unvaccinated patients accounted for the largest group despite having low comorbidities and also represented the largest group in intensive care units. Patients who had received two or three doses of Sinovac or two doses of Sinovac and one of BioNTech were older and had more comorbidities. The mean ages of these groups (vaccination groups 1, 3 and 4) were 69.3, 72.2, and 75.5 years, respectively. Hospitalizations in group 4 (2 doses of Sinovac + 1 dose of BioNTech) were lower than in group 3 (3 doses of Sinovac), and there were only three patients from group 4 who were admitted to the intensive care unit.

The vaccination status according to the age group is shown in Table 2. Among patients younger than 50 years, 322 of 445 (72.4%) were unvaccinated. On the other hand, nearly half (301/608, 49.5%) of the patients older than 64 years had two doses of Sinovac, while 32.9% of this age group were unvaccinated.

Vaccination status

0: unvaccinated, 1: two doses of Sinovac, 2: two doses of BioNTech, 3: three doses of Sinovac, 4: two doses of Sinovac + one dose of BioNTech, 5: one dose of Sinovac, 6: one dose of BioNTech, 7: two doses of Sinovac with or without BioNTech, but less than 14 days after the last dose. Female patients were older than male patients (61.1 vs. 58.4 years, p = 0.006) and had more comorbidities (mean 1.25 vs. 1.16). However, female patients were less common in the intensive care units than male patients (230/686, 34% vs. 299/715, 42%; χ2 = 10.2, p = 0.001).

Table 3 shows the correlation between intensive care hospitalizations and the number of comorbidities (p = 0.000). As the number of comorbidities increased, so did age and intensive care hospitalizations.

Sex, hospitalization status, and the number of comorbidities according to age groups are shown in Table 4.

Reasons for not getting vaccinated were identified in 566 patients. Negligence (n = 270, 48%) and hesitancy (n = 93, 16%) were two common reasons. While 203 patients (36%) were anti-vaccine.

Discussion

The course of the pandemic in Turkey is similar to that of other countries in the Northern Hemisphere facing the fourth wave; however, strict social restrictions controlled the first two peaks. The alpha variant dominated the third peak, and effective vaccines were available. In Turkey, inactivated vaccines (Sinovac) were primarily used in the third peak, while Western countries had mRNA or vector vaccines. Sinovac has also been used in Brazil, Chile, Indonesia, and China. During the third peak, the number of vaccinated people was limited in Turkey, but a significant decrease in healthcare worker death was observed after inoculation with Sinovac [12]. The hallmark of the fourth peak is the Delta variant and its rapid spread, mainly among unvaccinated people. Vaccination began in mid-January 2021 in Turkey, where healthcare workers were initially vaccinated, and the protocol was two doses of vaccine, 28 days apart. Only Sinovac was available until April 2021 when BioNTech was added as an option. At the beginning of July 2021, the government offered a third booster dose to healthcare workers and people > 50 years who had received two doses of Sinovac. Most people (> 90%) preferred BioNTech (96% of the authors of this article received BioNTech as their third dose). By August 10, 2021, 12 million, 30 million, and 6 million people had received one, two, and three doses, respectively, and nearly 19 million remained unvaccinated [10].

The results presented in Tables 1 and 2 should be evaluated and compared cautiously, because vaccine types and their accessibility were dependent on age group, comorbidities, and previous infection; therefore, only appropriate data are presented. Our study showed that nearly half of the hospitalized patients were unvaccinated, and the duration of protection after two doses of Sinovac may not be long enough. It also showed that the fourth wave of the pandemic affected people regardless of being vaccinated or not. Approximately half of the patients > 64 years had received two doses of Sinovac, which was more than the number of unvaccinated patients (301 vs. 200). However, it should be considered that 301 and 200 are absolute numbers rather than frequencies, and vaccination rates are higher among patients > 64 years. As 52% of the hospitalized patients were infected despite vaccination, it also indicates the importance of correct, adequate, and timely vaccination. The main limitation of our study is using absolute numbers instead of frequencies for vaccination rates due to unknown exact vaccination numbers. Therefore, Table 1 should be interpreted with caution. For example, the hospitalization rate in group 5 (only one dose of Sinovac) may seem low compared to that of group 1 (two doses of Sinovac), or the hospitalization rate of group 6 (one dose of BioNTech) is twice as large as that of group 5 (one dose of Sinovac). However, both these inferences are incorrect, because absolute numbers rather than frequencies are presented in Table 1. Since data regarding the total number of people with one or two doses of Sinovac or one dose of BioNTech were not available, comparisons between these groups could not be performed. In addition, only a few people in Turkey have received only one dose of Sinovac.

The development of several types of vaccines led to vaccine combinations and modifications of original protocols, most of which required two doses. In addition, impaired or reduced response to vaccines in immunocompromised and high-risk patients showed the need for booster doses. Booster doses can be categorized into two groups:

-

1. A third dose with the same vaccine: mRNA (Israel, USA) [13,14,15] or inactivated vaccine (Turkey)

-

2. A third dose with a different type of vaccine: two doses of inactivated vaccine followed by an mRNA vaccine (Turkey, Indonesia) [16] or a vector vaccine (Chili) [17].

The main reasons for using a different type of vaccine for the third booster dose are the decreased antibody titers with time [18] or in response to the Delta variant [19]. Turkey is the only country offering its population two different types of vaccine (mRNA or inactivated) as a booster dose which allowed us to compare them. Although the number of hospitalized patients after three doses was limited, the results suggest that the preference of BioNTech over Sinovac as the third dose in patients who had previously received two doses of Sinovac may be more effective in the prevention of hospitalization and severe disease. Since our study did not involve mild disease or mortality, more studies are needed to compare the effects of these vaccines. In addition to comparing the efficacy of two different vaccines as a booster, our study also justified the administration of a third dose, which the World Health Organization criticized considering the COVID-19 vaccine inequity in low-and middle-income countries [20].

Our results also showed that among the reasons people are not vaccinated, hesitancy and negligence prevailed over being anti-vaccine. This indicates that most people can be persuaded if provided with education and correct information. Misinformation spread by social media 21] is a serious threat to controlling the pandemic. The efforts of governments, healthcare workers, and community leaders are needed to control the current pandemic as well as for future pandemics and other global health problems.

In conclusion, effective vaccinations decrease COVID-19-related hospitalizations. Protection after two doses of Sinovac may not provide long-lasting immunity; however, a booster dose increases the immune response of patients who received two doses of Sinovac. In addition, most unvaccinated patients may be persuaded to undergo vaccination.

References

Covid-19 coronavirus pandemic. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (Accessed on 19 Aug 2021).

Francis AI, Ghany S, Gilkes T, et al. Review of COVID-19 vaccine subtypes, efficacy and geographical distributions. Postgrad Med J. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2021-140654.

Tregoning JS, Flight KE, Higham SL, et al. Progress of the COVID-19 vaccine effort: viruses, vaccines and variants versus efficacy, effectiveness and escape. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:626–36. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-021-00592-1 (Epub 2021 Aug 9. PMID: 34373623; PMCID: PMC8351583).

Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations. https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations (Accessed on 20 Aug 2021).

Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–15.

Logunov DY, Dolzhikova IV, Shcheblyakov DV, et al. Safety and efficacy of an rAd26 and rAd5 vector-based heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccine: an interim analysis of a randomised controlled phase 3 trial in Russia. Lancet. 2021;397:671–81.

Haas EJ, Angulo FJ, McLaughlin JM, et al. Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: an observational study using national surveillance data. Lancet. 2021;397:1819–29.

Jara A, Undurraga EA, González C, et al. Effectiveness of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in Chile. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:875–84. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2107715.

Tanriover MD, Doğanay HL, Akova M, et al. Efficacy and safety of an inactivated whole-virion SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (CoronaVac): interim results of a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial in Turkey. Lancet. 2021;398:213–22.

T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı Covid-19 Bilgilendirme Platformu. https://covid19.saglik.gov.tr/ (Accessed on 20 Aug 2021).

T.C. Sağlık Bakanlığı Covid-19 Bilgilendirme Platformu. https://covid19.saglik.gov.tr/TR-66935/genel-koronavirus-tablosu.html#. (Accessed on 20 Aug 2021).

Akpolat T, Uzun O. Reduced mortality rate after coronavac vaccine among healthcare workers. J Infect. 2021;83:e20–1.

Callaway E. COVID vaccine boosters: the most important questions. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-02158-6. Published 2021. Accessed 20 Aug 2021.

Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: FDA Authorizes Additional Vaccine Dose for Certain Immunocompromised Individuals. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-authorizes-additional-vaccine-dose-certain-immunocompromised. Published 2021. Accessed 20 Aug 2021.

Joint Statement from HHS Public Health and Medical Experts on COVID-19 Booster Shots. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/joint-statement-hhs-public-health-and-medical-experts-covid-19-booster-shots. Published 2021. Accessed 20 Aug 2021.

Indonesia considers COVID-19 booster shots for wider use -govt official. https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/indonesia-considers-covid-19-booster-shots-wider-use-govt-official-2021-07-27/. Published 2021. Accessed 20 Aug 2021.

Chile to give COVID-19 vaccine boosters for those inoculated with Sinovac. https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/chile-give-covid-19-vaccine-boosters-those-inoculated-with-sinovac-2021-08-05/. Published 2021. Accessed 20 Aug 2021.

Antibodies from Sinovac's COVID-19 shot fade after about 6 months, booster helps – study. https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/antibodies-sinovacs-covid-19-shot-fade-after-about-6-months-booster-helps-study-2021-07-26/. Published 2021. Accessed 20 Aug 2021.

Sanderson K. COVID vaccines protect against Delta, but their effectiveness wanes. Nature. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02261-8.

WHO calls for halting COVID-19 vaccine boosters in favor of unvaccinated. https://www.reuters.com/business/healthcare-pharmaceuticals/who-calls-moratorium-covid-19-vaccine-booster-doses-until-september-end-2021-08-04/. Published 2021. Accessed 20 Aug 2021.

The most influential spreader of coronavirus misinformation online. https://www.vaccineconfidence.org/latest-news/atjya28mehr7z4y-wgk2j-l8ddy-6tk9a-fptes-8wfgc-lx6y8-f5wrk-ybsb3-jzr4t-jclkh-9kbbf-76n72-xeckt-dsme3-6jgc5-wl54f. Published 2021. Accessed 20 Aug 2021.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Oğuz UZUN and Tekin AKPOLAT contributed to the study conception and design. Material preperation, data collection and analysis were performed by all authors. The first draft manuscript was written by Oğuz UZUN and Tekin Akpolat, all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have conflict of interest to declare.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Uzun, O., Akpolat, T., Varol, A. et al. COVID-19: vaccination vs. hospitalization. Infection 50, 747–752 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-021-01751-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-021-01751-1