Abstract

Injectable cosmetic wrinkle fillers are soft-tissue fillers approved as medical devices by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These devices are injected into the skin for correcting soft-tissue contour defects, such as moderate and severe wrinkles and folds, and for restoring the signs of facial fat loss in people with human immunodeficiency virus. Although the aesthetic treatment with injectable dermal fillers is considered to be safe, adverse events are involved with this minimally-invasive treatment. The FDA received 930 post-marked reports of adverse event from 2003 through 2008, of which 823 were deemed severe and 638 required medical treatment and follow-up.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The market for cosmetic aesthetic treatments is booming. Besides several minimally invasive rejuvenation methods, such as botulinum toxin, laser treatments, or radiofrequency therapies, dermal fillers have become an ever-increasingly popular means of addressing contour defects and soft-tissue augmentation [1••, 2, 3]. Statistical data from the The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery indicate that in 2011 more than 1,206,186 people were treated with hyaluronic acid injections in the United States. This places hyaluronic acid fillers in second place among the top five nonsurgical procedures of 2011 in the United States [4].

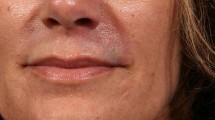

Injectable cosmetic wrinkle fillers are soft-tissue fillers approved as medical devices by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). These devices are injected into the skin for correcting soft-tissue contour defects, such as moderate and severe wrinkles and folds, and for restoring the signs of facial fat loss in people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [5]. Although the aesthetic treatment with injectable dermal fillers is considered to be safe, adverse events (AEs) are involved with this minimally invasive treatment [6]. The FDA received 930 post-marked reports of adverse event from 2003 through 2008, of which 823 were deemed severe and 638 required medical treatment and follow-up. The most frequently reported injection site was the nasolabial fold (35.6 %); however, the majority of reported AEs occurred in sites other than the nasolabial fold, such as lips, periorbital region, and perioral region [3].

This review will discuss the most commonly used soft-tissue fillers and the adverse reactions related to the treatment in order to evaluate the safety of injectable dermal fillers for the management of soft-tissue augmentation and for the treatment of facial lines and rhytids.

Filler Substances

Throughout the world, approximately 160 different injectable dermal fillers are currently available on the market. These different products can be distinguished in terms of their duration of effect in temporary and permanent injectable fillers. Further differentiation criteria includes the risk profile, the injection depth (dermal, subcutaneous, supraperiosteal) as well as the origin and production (human or cadaveric-derived, animal, bacterial fermentation, or synthesis) of the filler substance [7].

Temporary fillers are biodegradable and are absorbed through the human body after a period of time. The temporary effect lasts from 3 months to approximately 2 years and is highly dependent on the injected filler subtype, the area of treatment, the injection technique, and the amount injected. Frequently used temporary fillers are collagen, hyaluronic acid (HA), poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA), and calcium hydroxylapatite (CaHA) [1••, 8••]. Filler substances, such as polymethyl-methacrylate (PMMA) and silicone, are considered permanent by the FDA because the products are not absorbed by the human body [9, 10] (Table 1).

Temporary Fillers

Collagen is a natural protein that is a major component of the extracellular matrix of the skin and other connective tissues in the body. The collagen’s fiber architecture due to its triple-helix protein structure acts as the support structure for the skin and is essential for its mechanical stability. A loss of natural collagen due to aging and other factors leads to the thinning and atrophic appearance of both intrinsic and photoaging skin [11]. In 1981, bovine collagen (Zyplast®) was the first facial filler approved for cosmetic use in the United States. Besides bovine collagen, human-derived bioengineered (CosmoDerm®/CosmoPlast®) and porcine collagen (Evolence®) are used as dermal fillers [12–14]. All injectable collagen products are composed of lidocaine (approximately 0.3 %) and a phosphate-buffered saline solution of 35 mg/mL (up to 65 mg/mL) of collagen [15]. As of the drafting of the manuscript, no collagen filler is commercially available in the United States, but viewed in an international perspective injectable collagen fillers are still used for soft-tissue augmentation.

For more than two decades, collagen fillers were the most popular injectable implants in the United States until hyaluronic acid entered the market at the beginning of the 21st century [16]. Hyaluronic acid is an internally produced glycosaminoglycan and the most important polysaccharide in human extracellular matrix. HA is characterized by its high water storage capacity and also acts as a scaffold for collagen and elastin [17, 18]. When used as an injectable filler agent, hyaluronic acid consists of repeating polymer chains of the polysaccharide with interval cross-links of agents that bind the polymer together. By varying the amount and type of cross-linking material, the characteristics of the gel can vary in the degree of hardness, amount of lift, duration of survival, and resistance to degradation by heat or enzymes [17]. Nowadays HA has become the “gold standard” of injectable fillers since it was approved by the FDA in 2003 [19]. To date, four hyaluronic acid fillers have been approved for cosmetic use: Restylane®, Juvederm®, Perlane®, and Belotero® [20].

In 2006, calcium hydroxylapatite, known as Radiesse®, was approved by the FDA for the augmentation of moderate to severe facial lines and folds as well as for facial soft-tissue loss from HIV-related lipoatrophy [21]. This injectable filler substance consists of 30 % concentration of 25–45 μm of calcium hydroxylapatite spherical particles suspended in sodium carboxymethyl-cellulose (CMC) gel [17]. CaHA is characterized by an outstanding biocompatibility with the human body, because the particles are made of calcium and phosphate ions, which are identical to the mineral portion of bone [22].

In 2004, the FDA approved poly-L-lactic acid, known as Sculptra®, for the soft-tissue augmentation of facial atrophy and years later for the treatment of nasolabial folds and facial wrinkles [17, 23]. Sculptra® contains poly-L-lactic acid microspheres in a powdered form, is biocompatible, and resorbable. Because PLLA is a biostimulatory filler, the augmentation effect is less based on a direct volume boost but rather caused by a stimulation of fibroblasts and a growth of type-I collagen [9]. Therefore, Sculptra® is used for global volumetric augmentation of the mid and lower thirds of the face [24].

Permanent Fillers

In 2006, the FDA approved the first and only permanent injectable filler substance. Polymethylmethacrylate beads (PMMA microspheres) are known under the trade name Artefill® and are approved for the treatment of nasolabial folds [25]. ArteFill® is a gel suspension of 20 % polymethylmethacrylate homogeneous 30- to 42-μm microspheres in 3.5 % bovine collagen solution mixed with 0.3 % lidocaine. Because PMMA is a nonabsorbable synthetic substance, it is characterized by an extremely long-lasting effect [26].

Silicone comprises a large family of synthetic polymers containing the elemental silicone. The viscosity of these compounds is a function of the polymerization and cross-linkage of their molecules [27]. Solid silicone is used as implanted prosthetic devices, but as injectable dermal filler the liquid form, silicone oil or gel, is used [15, 27]. The FDA approved two forms of liquid silicone for retinal tamponade, namely AdatoSil (Bausch & Lomb) and Silikon 1000 (Alcon Labs) [28]. Even though the FDA did not approve these liquid silicones for injection to fill wrinkles or augment tissues in the body [29], there is tremendous off-label use. Therefore, silicones are a widely used material for cosmetic correction of small wrinkles and scars, as well as for volume augmentation of soft tissue in the face [15].

Adverse Events

Mild to severe side effects may occur with the use of injectable fillers [30•]. The occurrence of adverse events can be categorized in two main types: material-independent and material-dependent side effects [30•]. The FDA classifies adverse events as immediate, early, and delayed. Immediate AEs are those that present on the order of minutes to hours postprocedure. Early AEs are those presenting within days to weeks. Delayed AEs are defined as those presenting months to years later (Table 2).

Material-Independent Adverse Events

Adverse events are very common with any injectable dermal filler [6, 31]. Most AEs are related to incorrect injection technique or poor patient and localization selection [10]. Improper technique can lead to lumps and nodules after injection [31–33] or may result in deformity and asymmetry of the facial shape [9, 34, 35]. “Overcorrection” refers to the injection of too much product into an area and can result in visibility of the substance under the skin (Tyndall effect) or lumpiness at the site [1••]. The correct placement of product minimizes the risk of adverse events (Table 3).

Mild, immediate-onset complications often are related to the injection site and resolve spontaneously [9, 36]. Due to the gauge of the needle and the needle prick itself, the skin becomes mechanically traumatized in all facial augmentation procedures resulting in bruising, redness, swelling, pain, tenderness, itching, and rash [31, 35]. Larger-gauge needles become necessary for products with larger particle size. The use of these needles may translate into larger epithelial tears and greater disruption of dermal structures, with subsequent capillary leakage, edema, and stimulation of inflammatory cascades [9]. The frequency for complications also depends on the injection site. Anatomic areas that are considered more “sensitive,” including the periorbital area, may be at higher risk for unwanted side effects, such as bruising, swelling, and hematomas. These mild immediate-onset complications are usually related to the injection site and resolve spontaneously after a short duration [9, 36].

In rare cases, a bacterial infection with pathogenic microorganisms, such as Streptococcus aureus, may occur through the skin puncture, lead to systemic reactions, such as fever, leukocytosis, weight loss, and fatigue [9, 31]. In rare cases, the formation of biofilms can occur years after injection with any filler substance. Biofilm are defined as an aggregate of microorganisms, often bacteria, in which cells adhere to each other on a surface. Due to their notorious resistance to antibiotics, the development of biofilms is particularly feared because they are extremely difficult, if not impossible, to completely eradicate [37•]. Soft-tissue filler injection also may trigger herpes simplex virus (HSV) outbreaks [38]. Vascular interruption due to the injection increases the risk for local necrosis, palsies, and beading [39]. As reported in previous studies, the glabella region carries the greatest risk of necrosis [9]. A very rare but possible risk due to dermal filler injection is iatrogenic blindness. This tragic complication occurs from the injected filler flowing in a retrograde fashion to the ophthalmic artery. This risk increases large volumes are injected into the glabella region [9, 40••].

The development of an allergic reaction due to any filler substance is a possible but rare side effect. The exaggerated immune response of the body to the foreign substance occurs within minutes after exposure to a challenging antigen. The release of histamine leads to vascular permeability, edema, erythema, pain, and itching. Hypersensitivity skin reactions to injectable fillers can be mild, but cases of severe anaphylactic shocks due to the filler substance has been reported previously [31, 36]. Delayed hypersensitivity to the injected product can occur with cosmetic devices and may arise several months or years after injection [41]. The risk for allergic reaction is highly dependent on the filler material itself. Whereas hypersensitivity is rarely reported after injection with hyaluronic acid, the risk increases significantly with bovine collagen and other dermal wrinkle implants [16, 42].

Adverse Events Related to Temporary Fillers

Adverse reaction due to collagen injections can be separated into two main types: hypersensitive and nonhypersensitive side effect [16]. Nonhypersensitive side effects are usually related to the injection site, including bruising, erythema, and swelling. Herpetic or bacterial infections after collagen injection are a possible but rare and more frequently reported when injected at the glabella area [42]. Systemic complications, such as flulike symptoms, paresthesia, or difficulty breathing, also have been reported previously [43].

Approximately 3 % of the population is at risk of developing an allergic reaction due to bovine collagen implants. Delayed hypersensitivity response or severe anaphylactic shocks due to the collagen product are feared and serious side effects [44]. Rare hypersensitive reactions include the formation of foreign body granulomas at the injection site [45, 46], as well as cyst or abscess formation and necrosis [42, 47]. Therefore, a skin test is required 4 weeks before injection with bovine collagen [48, 49]. Because most treatment-associated allergic reactions occur shortly after the first treatment, some authors recommend a second allergy test 2–3 weeks after negative first test to reduce the risk for hypersensitive side effects [50, 51]. Human-derived collagen products do not include the risk of hypersensitive reactions [15].

The injection of hyaluronic acid is generally a very well-tolerated treatment and most reactions, of which redness is the most common, are mild or moderate in intensity and resolve within 2 to 3 months without treatment [52]. Pain and bruising are frequent and increase with the viscosity of the filler [52, 53]. A too superficial injection as well as an insufficient posttreatment massage in terms of product distribution in the tissue can increase the risk for temporary skin induration [54, 55] and nodules [6, 39]. The prevalence of adverse reactions is usually lower after the “touch-up” sessions than after the initial treatment session [52, 54]. The Tyndall effect from clear hyaluronic acid fillers can occur when the filler is placed too superficially or in patients with thin skin and minimal collagen support [56]. Herpetic recurrence is possible, especially after lip augmentation, according to injection technique [6, 19]. Scientific reports documented the rare incidence of localized granulomatous reactions, arterial embolization, bacterial infection, as well as acneiform and cystic lesions [6, 39]. The incidence of allergic skin reactions is low, approximately 0.6 % [19]. Hypersensitivity cases are defined as swelling, erythema, and tenderness, usually shortly after injection [9]. The risk for severe delayed reactions is very rare, but several case series reported late inflammatory reactions (on a mean of 2 months after injection), such as abscess formation, inflammation, and erythema [19].

The most common side effects of the treatment with calcium hydroxylapatite are edema and ecchymosis that persist approximately 1 to 3 weeks after injection [33, 57]. The complete resolution of edema may require months. Injection of CaHA into mid- or superficial dermis may result in visible white nodules and mild throbbing pain [58, 59]. The development of palpable nodules was reported frequently by lip mucosa augmentation subjects and by subjects who had treatment for radial lip lines. In this location, palpable nodules occur at a rate of 11.6 % [59]. Therefore, the injection of CaHA lip augmentation is contraindicated [9]. Nodules may be tender and typically occur in the first 2 to 4 weeks. Untreated, most nodules spontaneously resolve within 4 to 6 weeks, but some become permanent and may require surgical correction [33]. However, apart of the localization lip, the overall rate of nodule formation in general is very low [60] and has not been reported when calcium hydroxylapatite is injected into areas other than the lip [9].

One of the most common side effects associated with poly-l-lactic acid is the occurrence of (usually) nonvisible subcutaneous papules of approximately 2 to 5 mm [52, 61, 62]. These papules and nodules are typically palpable, asymptomatic, nonvisible, and may result from incorrect reconstruction, uneven product distribution in the suspension, imprecise injection technique (superficial injection), or lack of posttreatment massage [31, 52]. In most patients these lesions resolve spontaneously, but in rare case papules and nodules could persist for years [63]. The incidence of this side effect increases with superficial dermal injection. Therefore, injections into the dermis, particularly in thin dermis areas, such as upper lip, lower eyelids, glabella, and superficial wrinkles from the cheeks, are localizations with a high risk for any adverse event [35]. A rare complication due to the injection of PLLA is a foreign-body–induced granulomatous reaction, which can persist for several years [35, 64]. This delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the product also can be associated with persisting itching, edema, and erythema [65]. However, this adverse event occurs frequently in HIV-positive population and it can be assumed that the exaggerated immune response to this product it triggered by a weakened immune defense.

Adverse Events Related to Permanent Fillers

The treatment with polymethyl-methacrylate filler includes a relatively high risk for late-onset adverse reactions. As Zielke et al. [6] demonstrated, the interval between injection and development of side effects is significantly longer compared with other injectable fillers. The mean time until appearance was 37.1 ± 25.4 months with a maximum reported time of 6.5 years between injection and reaction. Chronic inflammatory reactions for example are frequently reported due to PMMA injection and usually happen years after injection. These infections can be related to a triggering event, such as another operation or infection in the area previously injected [66]. Although the rate is very low (0.01 %), the risk for hypersensitive and allergic reactions is possible due to PMMA containing bovine collagen. Product sensitivity tends to occur from 6 to 24 months posttreatment [9]. Skin testing is mandatory before use of this agent [9]. According to manufacturer’s data, the rate of granulomatous reaction is 1 in 1,000 patients. Nodules arise 6 months to 2 years after treatment [6, 66] and can involve local tissue necrosis [9]. When PMMA is injected too superficially, the risk is high for hypertrophic scarring and keloids [67]. In this context, lumpiness and visible bumps at injection area are frequent, which can persist for more than 1 month after injection and sometimes for years [25].

The off-label use of liquid silicone used as dermal filler may cause several undesired side effects [10]. Temporary mild bruising, edema, dyschromia, swelling, pain, erythema, and bleeding may occur during or right after injection. In some cases, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation occurs [68]. Overcorrection is a technique-dependent complication that results in small nodular elevation shortly after injection. Nodules are caused by excessive amounts of product injected or when injected too superficially. Localizations with very thin skin, such as periorbital area, are much more affected by the development of underlying nodules [10, 68]. Skin texture alterations are reported due to an exaggerated proliferative fibrohistolytic response [10]. Serious adverse events and delayed reactions due to silicone injection occur usually years after treatment. Inflammatory responses with foreign body cells, massive skin necrosis, or granulomatous rosacea-like eruptions were reported [28]. Due to reorganizations of facial tissue and an increasing loss of subcutaneous fat, demarcation of implanted silicone is possible during the aging process. Especially with large volumes of injected liquid silicone, there is a general risk for migration or excessive capsule formation in the course of years or the implant forms thick-walled cystic spaces [69, 70].

Prevention and Managing of Dermal Filler Complications

Although treatment with injectable fillers is a minimally invasive event, there is a potential risk for unwanted side effects. Every injection does cause immediate, mild AEs, such as redness, bruising, swelling, and pain. These side effects are strongly related to the injection site and resolve spontaneously within a short time after injection. However, measures may be implemented to prevent these common immediate AEs, such as antecedent avoidance of blood thinning medications or foods, and the application of topical anesthetic or cold packs to induce vasoconstriction (Table 3). Early AEs, which require monitoring, most often are due to poor technique or improper placement of the material, including vascular occlusion, skin necrosis, palsies, and beading, or cyst formation. Measures to prevent such AEs include pulling back on the syringe to ensure that the needle is not intravascularly placed and administration of the material in small aliquots. It is the author’s (MAA) opinion that tunneling should be avoided in order to prevent inadvertent vascular occlusion.

Delayed-type hypersensitivity may appear after days to weeks as redness and swelling and should be promptly treated with topical corticosteroid. Delayed AEs manifesting over the course of months to years include granuloma formation, nodularity, or scarring. These are observed most often with PLLA, CaHA, and PMMA. Such nodules require repeated intralesional corticosteroid to improve. Other delayed AEs include lymphedema and ductal occlusions, observed most commonly in the under-eye region. Over the course of months to years, HA may undergo partial digestion by native hyaluronidases, resulting in smaller molecular weight HA and greater water absorption, which may explain the delayed nodules, lymphedema, and occlusive AEs that have been observed. Treatment of this complication with hyaluronidase is most effective to dissolve the residual HA.

Finally, permanent fillers, such as PMMA and silicone, which are appreciated for their longevity, are well known for delayed complications, in many instances 8 to 10 years after injection. Discoloration of silicone filler is a well-known late-stage complication, for which no treatment exists other than surgical excision. Biofilms, notorious for their resistance to antibiotics, may require a multiple antibiotic regimen over a long course. The management of these reactions often is difficult and of long duration.

Conclusions

During the past two decades, injectable dermal fillers for aesthetic enhancement have increased dramatically in their use and have become a very popular means to correct contour defects and for soft-tissue augmentation. Although, more than 160 dermal filler products are on the market, one can still argue that the “perfect” filler has not been found yet.

Currently available fillers are considered to be very safe, but as with any minimally invasive treatment there is a potential risk for unwanted side effects. The intensity of these adverse events strongly depends on the used filler substance. Whereas complications with temporary soft-tissue fillers are usually minor and easy-to-treat, the risk for severe side effects significantly increases with more durable filler substances. Especially the off-label use of silicone-based fillers is known for delayed complications, usually 8 to 10 years after injection. This particular case shows that it is difficult to make a point regarding safety of dermal fillers; short-term studies investigating the safety and efficacy of dermal fillers are frequent, but the important long-term safety is not yet fully clarified. More studies with long-term safety and efficacy data are required before definitive statements regarding dermal fillers can be made. The practitioner should be knowledgeable about available procedures, limitations, best techniques, risks, and the medical management of adverse events.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

•• Sturm LP, Cooter RD, Mutimer KL, Graham JC, Maddern GJ. A systematic review of dermal fillers for age-related lines and wrinkles. ANZ J Surg. 2011;81(1-2):9–17. This systematic review provides an exhaustive summary of literature relevant to soft tissue augmentation with dermal fillers.

Beasley KL, Weiss MA, Weiss RA. Hyaluronic acid fillers: a comprehensive review. Facial Plast Surg. 2009;25(2):86–94.

Hanke CW, Rohrich RJ, Busso M, Carruthers A, Carruthers J, Fagien S, et al. Facial soft-tissue fillers conference: assessing the state of the science. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(4 Suppl):S66–85. S85.e1–136.

American Society Plastic Surgeons. Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank. Available from: http://www.surgery.org/sites/default/files/ASAPS-2011-Stats.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2012.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Wrinkle relief: injectable cosmetic fillers. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ConsumerUpdates/ucm049349.htm. Accessed July 15, 2012.

Zielke H, Wölber L, Wiest L, Rzany B. Risk profiles of different injectable fillers: results from the Injectable Filler Safety Study (IFS Study). Dermatol Surg. 2008;34(3):326–35.

Pavicic T. Fillers. An overview. Hautarzt. 2009;60(3):233–43.

•• Sclafani AP, Fagien S. Treatment of injectable soft tissue filler complications. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35 Suppl 2:1672–80. This review gives advises how to deal with complications due to soft tissue fillers.

Cox SE, Adigun CG. Complications of injectable fillers and neurotoxins. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24(6):524–36.

Hexsel DM, Hexsel CL, Iyengar V. Liquid injectable silicone: history, mechanism of action, indications, technique, and complications. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2003;22(2):107–14.

Monheit GD. Advances in collagen fillers. J Drugs Dermatol 2009;8:812–17.

Kontis TC, Rivkin A. The history of injectable facial fillers. Facial Plast Surg. 2009;25(2):67–72.

Knapp TR, Kaplan EN, Daniels JR. Injectable collagen for soft tissue augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;60(3):398–405.

Stegman SJ. Injectable collagen. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80(6):866.

Requena L, Requena C, Christensen L, Zimmermann US, Kutzner H, Cerroni L. Adverse reactions to injectable soft tissue fillers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(1):1–34.

Baumann L, Kaufman J, Saghari S. Collagen fillers. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19(3):134–40.

Glogau RG. Fillers: from the past to the future. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2012;31(2):78–87.

Olenius M. The first clinical study using a new biodegradable implant for the treatment of lips, wrinkles, and folds. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1998;22(2):97–101.

Andre P. New trends in face rejuvenation by hyaluronic acid injections. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2008;7(4):251–8.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/. Accessed July 15, 2012.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approval letter-Radiesse. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf5/P050037a.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2012.

Marmur ES, Phelps R, Goldberg DJ. Clinical, histologic and electron microscopic findings after injection of a calcium hydroxylapatite filler. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2004;6(4):223–6.

Nguyen AT, Ahmad J, Fagien S, Rohrich RJ. Cosmetic medicine: facial resurfacing and injectables. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(1):142e–53e.

Lacombe V. Sculptra: a stimulatory filler. Facial Plast Surg. 2009;25(2):95–9.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Approval letter- Artefill. Available from: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf2/p020012a.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2012.

Lemperle G, Romano JJ, Busso M. Soft tissue augmentation with artecoll: 10-year history, indications, techniques, and complications. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29(6):573–87.

Camacho D, Machan S, Pilesanski U, Revelles JM, Martín L, Requena L. Generalized livedo reticularis induced by silicone implants for soft tissue augmentation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34(2):203–7.

Duffy DM. Liquid silicone for soft tissue augmentation. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(11 Pt 2):1530–41.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Wrinkle fillers. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/CosmeticDevices/WrinkleFillers/default.htm. Accessed October 15, 2012.

• Luebberding S, Alexiades-Armenakas M. Safety of dermal fillers. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(9):1053–8. This article reviews complications due to innovative cell therapy, such as Autologous Fibroblast Cell Therapy (AFCT), Platelet-rich Plasma (PRP), and Adipose-Derived Stem Cells (ADSC).

Lowe NJ, Maxwell CA, Patnaik R. Adverse reactions to dermal fillers: review. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(11 Pt 2):1616–25.

Duranti F, Salti G, Bovani B, Calandra M, Rosati ML. Injectable hyaluronic acid gel for soft tissue augmentation. A clinical and histological study. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24(12):1317–25.

Tzikas TL. Evaluation of the radiance FN soft tissue filler for facial soft tissue augmentation. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2004;6(4):234–9.

Sclafani AP. Safety, efficacy, and utility of platelet-rich fibrin matrix in facial plastic surgery. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2011;13(4):247–51.

Vochelle D. The use of poly-L-lactic acid in the management of soft-tissue augmentation: a five-year experience. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2004;23(4):223–6.

Niamtu 3rd J. Complications in fillers and Botox. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2009;21(1):13–21.

• Rohrich RJ, Monheit G, Nguyen AT, Brown SA, Fagien S. Soft-tissue filler complications: the important role of biofilms. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(4):1250–6. This review helps to understand the potential role of soft-tissue filler in the formation of biofilm, and how to avoid this complication, thereby increasing the safety of injectable fillers.

Narins RS, Jewell M, Rubin M, Cohen J, Strobos J. Clinical conference: management of rare events following dermal fillers–focal necrosis and angry red bumps. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(3):426–34.

Friedman PM, Mafong EA, Kauvar ANB, Geronemus RG. Safety data of injectable nonanimal stabilized hyaluronic acid gel for soft tissue augmentation. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28(6):491–4.

•• Lazzeri D, Agostini T, Figus M, Nardi M, Pantaloni M, Lazzeri S. Blindness following cosmetic injections of the face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(4):995–1012. This article explains the rare but possible risk for blindness following cosmetic injections in the face, and how to avoid this serious adverse event.

Narins RS, Bowman PH. Injectable skin fillers. Clin Plast Surg. 2005;32(2):151–62.

Hanke CW, Higley HR, Jolivette DM, Swanson NA, Stegman SJ. Abscess formation and local necrosis after treatment with Zyderm or Zyplast collagen implant. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25(2 Pt 1):319–26.

Douglas RS, Donsoff I, Cook T, Shorr N. Collagen fillers in facial aesthetic surgery. Facial Plast Surg. 2004;20(2):117–23.

Mullins RJ, Richards C, Walker T. Allergic reactions to oral, surgical and topical bovine collagen. Anaphylactic risk for surgeons. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1996;24(3):257–60.

Overholt MA, Tschen JA, Font RL. Granulomatous reaction to collagen implant: light and electron microscopic observations. Cutis. 1993;51(2):95–8.

Brooks N. A foreign body granuloma produced by an injectable collagen implant at a test site. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1982;8(2):111–4.

McCoy Jr JP, Schade WJ, Siegle RJ, Waldinger TP, Vanderveen EE, Swanson NA. Characterization of the humoral immune response to bovine collagen implants. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121(8):990–4.

Kamer FM, Churukian MM. Clinical use of injectable collagen. A three-year retrospective review. Arch Otolaryngol. 1984;110(2):93–8.

Siegle RJ, McCoy Jr JP, Schade W, Swanson NA. Intradermal implantation of bovine collagen. Humoral immune responses associated with clinical reactions. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120(2):183–7.

Klein AW. In favor of double testing. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15(3):263.

Klein AW. Collagen substances. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2001;9(2):205–18. viii.

Narins RS, Brandt F, Leyden J, Lorenc ZP, Rubin M, Smith S. A randomized, double-blind, multicenter comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of Restylane versus Zyplast for the correction of nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29(6):588–95.

Baumann LS, Shamban AT, Lupo MP, Monheit GD, Thomas JA, Murphy DK, et al. Comparison of smooth-gel hyaluronic acid dermal fillers with cross-linked bovine collagen: a multicenter, double-masked, randomized, within-subject study. Dermatol Surg. 2007;33 Suppl 2:S128–35.

Lindqvist C, Tveten S, Bondevik BE, Fagrell D. A randomized, evaluator-blind, multicenter comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of Perlane versus Zyplast in the correction of nasolabial folds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(1):282–9.

DeLorenzi C, Weinberg M, Solish N, Swift A. Multicenter study of the efficacy and safety of subcutaneous non-animal-stabilized hyaluronic acid in aesthetic facial contouring: interim report. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32(2):205–11.

Cox SE. Clinical experience with filler complications. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35 Suppl 2:1661–6.

Bass LS, Smith S, Busso M, McClaren M. Calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse) for treatment of nasolabial folds: long-term safety and efficacy results. Aesthet Surg J. 2010;30(2):235–8.

Berlin A, Cohen JL, Goldberg DJ. Calcium hydroxylapatite for facial rejuvenation. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2006;25(3):132–7.

Jansen DA, Graivier MH. Evaluation of a calcium hydroxylapatite-based implant (Radiesse) for facial soft-tissue augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(3 Suppl):22S–30S.

Goldberg DJ. Breakthroughs in US dermal fillers for facial soft-tissue augmentation. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2009;11(4):240–7.

Vleggaar D. Soft-tissue augmentation and the role of poly-L-lactic acid. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(3 Suppl):46S–54S.

Engelhard P, Humble G, Mest D. Safety of Sculptra: a review of clinical trial data. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2005;7(3–4):201–5.

Valantin M-A, Aubron-Olivier C, Ghosn J, Laglenne E, Pauchard M, Schoen H, et al. Polylactic acid implants (New-Fill) to correct facial lipoatrophy in HIV-infected patients: results of the open-label study VEGA. AIDS. 2003;17(17):2471–7.

Salles AG, Lotierzo PH, Gimenez R, Camargo CP, Ferreira MC. Evaluation of the poly-L-lactic acid implant for treatment of the nasolabial fold: 3-year follow-up evaluation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32(5):753–6.

Beljaards RC, De Roos K-P, Bruins FG. NewFill for skin augmentation: a new filler or failure? Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(7 Pt 1):772–6. discussion 776.

Salles AG, Lotierzo PH, Gemperli R, Besteiro JM, Ishida LC, Gimenez RP, et al. Complications after polymethylmethacrylate injections: report of 32 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(5):1811–20.

Cohen JL. Understanding, avoiding, and managing dermal filler complications. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34 Suppl 1:S92–9.

Selmanowitz VJ, Orentreich N. Medical-grade fluid silicone. A monographic review. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1977;3(6):597–611.

Duffy DM. The silicone conundrum: a battle of anecdotes. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28(7):590–4.

Rapaport M. Silicone injections revisited. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28(7):594–5.

Conflict of Interest

Stefanie Luebberding declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Macrene Alexiades-Armenakas declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Luebberding, S., Alexiades-Armenakas, M. Critical Appraisal of the Safety of Dermal Fillers: A Primer for Clinicians. Curr Derm Rep 2, 150–157 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13671-013-0042-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13671-013-0042-1