Abstract

Purpose of Review

It is estimated that over 400 million people worldwide are living with diabetes. Excess adiposity is the strongest risk factor for non-insulin-dependent diabetes, type 2. Lifestyle interventions have demonstrated that diet plays a critical role in preventing the onset of type 2 diabetes. Dietary fat is not only a source of energy and nutrients, but also bioactive fatty acids.

The purpose of this review was to examine data from recent prospective cohort studies and dietary interventions to determine if there are benefits to fat consumption on diabetes risk.

Recent Findings

The consumption of fish and marine n-3 fatty acids among Asian populations and regular-fat dairy foods and trans-palmitoleic acid (trans-16, n-7) among Western populations may be associated with reduced risk for type 2 diabetes.

Summary

Whereas some dietary fat may contribute to reduced diabetes risk, lifestyle recommendations to balance calories with physical activity are prudent at this time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus, a group of metabolic disorders characterized by increased blood glucose concentration, increases the risk for morbidity and mortality [1]. It was estimated in 2015 that worldwide, 415 million people, 20–79 years of age, were living with diabetes and 5 million deaths could be attributed to it [1]. The global estimated healthcare costs associated with the disease were 673 billion US dollars [1]. Further, it is estimated that by 2040, the number of people living with diabetes will increase by approximately 55% [1].

The dramatic global increase in the prevalence of diabetes is associated with the global obesity epidemic, particularly because excess adiposity is the strongest risk factor for non-insulin-dependent diabetes, also known as type 2 diabetes [2, 3]. The Diabetes Prevention Program, a lifestyle intervention that promotes weight loss through energy-restriction and physical activity, was shown in a clinical trial to reduce the incidence of type 2 diabetes more effectively than pharmacological intervention, indicating that diet can play a critical role in preventing the onset of type 2 diabetes [4].

Whereas it is recognized that an overall healthy dietary pattern that promotes 30–40% of calories from low-glycemic index carbohydrates is effective at promoting improved glycemic control [5], the effects of dietary fat on diabetes risk are less understood. Dietary fat is not only a source of energy and nutrients, but also bioactive fatty acids that affect cell metabolism [6]. The purpose of this review was to examine the data from recent prospective cohort studies and randomized clinical trials to determine if there are benefits to fat consumption on risk for type 2 diabetes.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

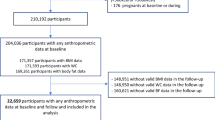

PubMed was searched for original research articles and meta-analyses/systematic reviews conducted in humans over the last 10 years (2008–August 2018). Search terms included “dietary fat,” “monounsaturated fat,” “polyunsaturated fat,” “saturated fat,” and “trans-fat” in combination with “diabetes,” “type 2 diabetes,” and “diabetes risk.” Prospective cohort studies and randomized clinical trials that assessed incidence and risk of type 2 diabetes were included in the review. The reference lists of selected articles were also reviewed for relevant literature.

The search yielded mostly articles published on observational findings from prospective cohort studies. Dietary data collected from food frequency questionnaires and fatty acid biomarker data collected from plasma and serum samples indicated that the majority of research pertaining to dietary fat and fatty acids and risk for type 2 diabetes can be categorized by classes of fatty acids, such as n-3, saturated, trans-, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated, as well as by their primary food sources, such as fish, meat and dairy, and plant oils. Each of these categories is discussed in this review.

Associations Between Fish, Marine Sources of n-3 Fatty Acids, and Risk for Type 2 Diabetes

A body of prospective research investigating the associations between fish (a predominant source of n-3 fatty acids) and n-3 fatty acid consumption on risk for type 2 diabetes indicates opposing findings depending on geographical location of study. According to findings from five meta-analyses, whereas fish and marine n-3 fatty acid consumption among Asian populations was associated with a decreased risk for type 2 diabetes, fish and marine n-3 fatty acid consumption among western Europeans and Americans was associated with increased incidence of the disease [7,8,9, 10•, 11]. Zhou et al. [11] reported that consuming fish about four times per month and consuming about 0.1 g of marine n-3 fatty acids per day increased the risk for type 2 diabetes. These results were based on 13 prospective cohort studies conducted in Western populations. Zheng et al. [10•], however, showed that in pooled analyses from 24 prospective cohorts, that whereas studies conducted in Western populations observed positive associations between fish and marine n-3 fatty acid consumption and type 2 diabetes, those studies conducted in Asian populations observed an inverse association. Meta-analyses by Wu et al. [9] and Wallin et al. [8], which utilized many of the same data sets, also reported opposing risks depending on geographical location of study. Muley et al. [7] reported similar findings but indicated that marine n-3 fatty acids were associated with reduced risk for type 2 diabetes in Australian cohorts as well as in Asian cohorts. A more recent prospective study from the Australian Longitudinal Study of Women’s Health, conducted in 8370 women, 45–50 years of age, however, indicated that total n-3 fatty acids were associated with a 55% increased risk of incident type 2 diabetes in Australian women (Table 1) [17]. These data indicate that fish and marine n-3 fatty acid consumption may reduce risk for type 2 diabetes among Asian populations but may be detrimental to Westerners.

Implications for a connection between fish and marine n-3 fatty acid consumption and risk for type 2 diabetes among Westerners should be taken with caution, however, because the meta-analyses reviewed were based on many of the same heterogeneous data sets taken from various cohorts in western Europe and the USA [7,8,9, 10•, 11]. Whereas analyzing the data by subgroup homogenized the datasets from Asian populations, data among Westerners remained heterogeneous [10•]. No clinical trials have shown that fish consumption or marine n-3 fatty acids contribute to diabetes risk [5]. Further, biomarker data from prospective cohorts that aimed to assess the fatty acids present in human plasma and serum and risk for type 2 diabetes indicate no increased risk associated with marine n-3 fatty acids and type 2 diabetes among two Finnish cohorts and one American cohort (Table 2) [28, 29, 33]. Data from Finnish men enrolled in the Metabolic Syndrome in Men Study indicated that total n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids elucidated from erythrocyte membranes were not associated with worsening hyperglycemia or type 2 diabetes [28]. Data from another cohort of Finnish men, from the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study, indicated that the highest versus the lowest quartile of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) + docosapentaenoic acid (DPA) + docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) from serum was associated with 33% lower risk for type 2 diabetes [29]. Similarly, in a US cohort of men and women from the multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), higher diabetes incidence was observed for individuals with serum total n-3 fatty acid levels below the 75th percentile [33]. No associations with diabetes were observed for those with serum total n-3 fatty acids above the 75% percentile [33]. Whereas these data indicate no detrimental association between serum and plasma n-3 fatty acids and type 2 diabetes in Western cohorts, it is still difficult to draw any definitive conclusions based on them. Data from erythrocyte membranes give short-term insight into diet, and it is unclear from the Metabolic Syndrome in Men and MESA cohorts what the dietary sources of n-3 fatty acids were. Current available evidence indicates that fish and marine n-3 fatty acid consumption may reduce the risk for type 2 diabetes in Asian populations and that more research is necessary to better understand the associations between fish, marine n-3 fatty acids, and type 2 diabetes among Western populations.

Associations Between Dairy Foods, Ruminant Sources of Fatty Acids, and Risk for Type 2 Diabetes

Current dietary recommendations promote dietary patterns that are low in saturated and trans-fat and are associated with reduced risk for chronic diseases [38]. Within those dietary patterns, dairy foods including milk, cheese, and yogurt are recommended in low-fat and fat-free varieties [38]. Whole (4% milk fat) and reduced-fat (2% milk fat) dairy foods, known collectively as “regular fat dairy,” however, and the saturated and trans-fatty acids that are derived from them have been associated with a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes [15, 18, 19, 23••, 35, 39].

In a prospective study of Australian men and women, whereas total dairy consumption was not associated with type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome, a leading risk factor for the development of type 2 diabetes, the highest versus the lowest quartile of regular-fat dairy consumption was inversely associated with metabolic syndrome [18]. Further, in a cohort of Swedish men and women, the highest versus the lowest quintile of regular-fat dairy consumption was associated with 23% less incidence of type 2 diabetes [19].

Milk fat is a complex mixture of many fatty acids of varying chain lengths with different degrees of saturation. Several of the fatty acids derived from milk have been neutrally or inversely associated with type 2 diabetes in prospective analyses. A meta-analysis designed to investigate the associations between saturated and trans-fat consumption and risk for chronic diseases indicated that saturated fat consumption was not associated with type 2 diabetes and ruminant derived trans-palmitoleic acid (trans-16:1, n-7) was associated with 42% lower risk for type 2 diabetes [39]. Four large cohorts, the Cardiovascular Health Study, the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, the Nurses’ Health Study, and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study cohorts, were included in the meta-analysis. Prospective biomarker data from these cohorts indicated inverse associations between circulating trans-palmitoleic acid (trans-16:1, n-7) and insulin resistance [25, 40] and incident type 2 diabetes [25, 35, 40]. Data from a smaller cohort from the USA, however, indicated that serum trans-palmitoleic acid (trans-16:1, n-7) had no association with risk for type 2 diabetes [27].

Prospective studies have also indicated an inverse association between saturated fats derived from dairy foods and type 2 diabetes. In Swedish men and women from the Malmö Diet and Cancer Cohort, the highest versus the lowest quintiles of saturated fatty acids with four to ten carbons, lauric acid (12:0), and myristic acid (14:0) were associated with decreased risk for type 2 diabetes [19]. The dietary assessment was an interview-based diet history method that combined a diet-recall and food-frequency questionnaire with the interview [19]. Biomarker data from plasma fatty acids has also indicated inverse associations between milk fat consumption and reduced risk for type 2 diabetes. Prospective data from 659 multi-ethnic men and women from the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study and 3333 men and women from the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study indicated that serum pentadecanoic acid (15:0), a short-term marker of milk fat consumption, was associated with 27% and 44% lower incidence of type 2 diabetes, respectively [27, 35]. Heptadecanoic acid (17:0), another short-term marker of milk fat consumption, was also inversely associated with type 2 diabetes in the Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-Up Study cohorts [35]. Concerns have been raised about the use of pentadecanoic acid (15:0), heptadecanoic acid (17:0), and trans-palmitoleic acid (trans-16:1, n-7) as biomarkers of dairy intake. These fatty acids are not exclusive to dairy fat [41•]. Further, trans-palmitoleic acid (trans-16:1, n-7) can be synthesized endogenously from vaccenic acid (trans-18:1, n-11), the predominant trans fatty acid isomer in dairy fats, but one also present in partially hydrogenated fats and oils [41•]. Finally, the methods used to analyze fatty acids need to be optimized to properly elucidate each fatty acid; thus, it is difficult to ensure that the biomarker data were not exaggerated by errors in methodology [41•]. Publications that used pentadecanoic acid (15:0), heptadecanoic acid (17:0), and trans-palmitoleic acid (trans-16:1, n-7) as biomarkers of dairy consumption did, however, correlate findings with data obtained from self-reported dietary recalls and food frequency questionnaires, which have also been brought into question. With those limitations considered, current available evidence indicates a possible inverse association between regular fat dairy consumption and risk for type 2 diabetes.

Meat, Saturated Fat from Animal Sources, and Risk for Type 2 Diabetes

A prospective analysis of associations between food sources rich in saturated fatty acids and incidence of type 2 diabetes from 3349 Spanish men and women from the PREvención con DIeta MEDiterránea (PREDIMED) study indicated that whereas total dietary fat, monounsaturated fatty acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and trans-fatty acids were not associated with type 2 diabetes, the highest versus the lowest quartile of saturated and animal fat consumption was associated with the incidence of type 2 diabetes [21]. These findings were in agreement with those from the Malmö Diet and Cancer Cohort in which the highest versus the lowest quintile of meat consumption was associated with increased risk for type 2 diabetes [19]. Whereas these data indicate an association between meat consumption and risk for type 2 diabetes, more research is necessary to test these observations.

Vegetable Oils, n-3 Monounsaturated and Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids, and Risk for Type 2 Diabetes

Prospective data from the Nurses’ Health Studies (I and II) indicated after 22 years of follow-up, that women who consumed greater than one tablespoon (approximately 8 g) of olive oil per day compared to those who never consumed olive oil had 10% lower risk of incident type 2 diabetes [20]. The predominant fatty acid in olive oil is oleic acid (18:1, n-9), a monounsaturated fatty acid. One prospective study of Finnish men from the Metabolic Syndrome in Men Study, however, indicated that fasting serum total monounsaturated fatty acids and oleic acid (18:1, n-9) predicted worsening of hyperglycemia and were associated with increased odds of developing type 2 diabetes [26]. Whereas results from these two prospective cohorts are in direct opposition to one another, as stated previously results from the PREDIMED study indicated no association between total monounsaturated fatty acid consumption and risk for type 2 diabetes [21], and results from two dietary interventions support an inverse association between monounsaturated fatty acid consumption and insulin sensitivity, a risk factor for type 2 diabetes [42, 43]. In a randomized, parallel design study conducted in 55 men and 76 women, 28 years of age on average, a moderate-fat diet containing 35–45% of energy and greater than 20% of energy as monounsaturated fatty acids decreased fasting insulin by 2.6 ± 3.6 pmol/L and the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance by 0.17 ± 0.13 when compared to a low-fat diet containing 20–30% of energy from fat or a control diet containing 35% of energy from fat [42]. Similarly, in a cross-over feeding intervention among 164 men and women from the Optimal Macronutrient Intake Trial to Prevent Heart Disease (OmniHeart), an unsaturated fat-rich diet made up of predominantly monounsaturated fatty acids increased the quantitative insulin sensitivity check index significantly more than a carbohydrate-rich diet similar to the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet or a protein-rich diet predominantly from plant sources [43].

Vegetable oils are also leading dietary sources of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as α-linolenic acid, which can also be derived from nuts, milk, and meat. In a cohort of over 3000 elderly American men and women from the Cardiovascular Health Study, the highest versus the lowest quartile of plasma α-linolenic acid was associated with 43% lower risk for type 2 diabetes [24]. In a cohort of Chinese men and women from the Singapore Chinese Health Study, non-marine α-linolenic acid and n-3 fatty acids were inversely associated with self-reported incidence of type 2 diabetes [13]. In a cohort of over 36,000 women from the Women’s Health Study, plant-based n-3 fatty acids were not associated with incident diabetes [14]. In a cohort of Australian women from the Australian Longitudinal Study of Women’s Health, however, total n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and α-linolenic acid were associated with validated, self-reported incidence of type 2 diabetes [17]. To date, no dietary interventions have been conducted showing a detrimental effect of plant-derived n-3 fatty acids and type 2 diabetes. Collectively, the data indicate that vegetable oils, total monounsaturated fatty acids, and n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids do not contribute to risk for type 2 diabetes.

Conclusion: Are There Benefits to Fat Consumption on Risk for Type 2 Diabetes?

Dietary fat is a complex umbrella term that does not provide specific details regarding chain length, degree of saturation, or food source. The observational, biomarker, and clinical research published over the last decade indicates that total dietary fat consumption is not associated with risk for type 2 diabetes. Data from prospective cohort studies indicate that some fats may be particularly beneficial in reducing the risk for type 2 diabetes. In Asian populations, the consumption of fish and marine n-3 fatty acids has been associated with reduced risk for type 2 diabetes. In Western cohorts, reduced risk for type 2 diabetes has been associated with the consumption of regular-fat dairy foods and trans-palmitoleic acid (trans-16, n-7). Of the utmost importance, however, is that humans do not eat dietary fats and fatty acids in isolation. Humans eat foods, not nutrients, and based on dietary interventions that tested overall dietary patterns, low-fat dietary patterns have not been demonstrated to increase the risk for, or significantly reduce the incidence of, type 2 diabetes [37, 44]. Whereas some dietary fat may help contribute to a reduced risk for type 2 diabetes, the lifestyle recommendation to balance caloric intake with physical activity is prudent at this time.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Ogurtsova K, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Huang Y, Linnenkamp U, Guariguata L, Cho NH, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;128:40–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2017.03.024.

Hu FB, van Dam RM, Liu S. Diet and risk of type II diabetes: the role of types of fat and carbohydrate. Diabetologia. 2001;44(7):805–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001250100547.

Ley SH, Hamdy O, Mohan V, Hu FB. Prevention and management of type 2 diabetes: dietary components and nutritional strategies. Lancet. 2014;383(9933):1999–2007. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60613-9.

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa012512.

Via MA, Mechanick JI. Nutrition in type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome. Med Clin North Am. 2016;100(6):1285–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2016.06.009.

Acosta-Montano P, Garcia-Gonzalez V. Effects of dietary fatty acids in pancreatic beta cell metabolism, implications in homeostasis. Nutrients. 2018;10(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10040393.

Muley A, Muley P, Shah M. ALA, fatty fish or marine n-3 fatty acids for preventing DM?: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2014;10(3):158–65.

Wallin A, Di Giuseppe D, Orsini N, Patel PS, Forouhi NG, Wolk A. Fish consumption, dietary long-chain n-3 fatty acids, and risk of type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(4):918–29. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc11-1631.

Wu JH, Micha R, Imamura F, Pan A, Biggs ML, Ajaz O, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and incident type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2012;107(Suppl 2):S214–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114512001602.

• Zheng JS, Huang T, Yang J, Fu YQ, Li D. Marine N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are inversely associated with risk of type 2 diabetes in Asians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44525. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0044525 This systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies examined the associations of fish and n -3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake with type 2 diabetes risk. The pooled analysis allowed for differences between Asian and Western cohorts to emerge.

Zhou Y, Tian C, Jia C. Association of fish and n-3 fatty acid intake with the risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Br J Nutr. 2012;108(3):408–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114512002036.

Kaushik M, Mozaffarian D, Spiegelman D, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids, fish intake, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90(3):613–20. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2008.27424.

Brostow DP, Odegaard AO, Koh WP, Duval S, Gross MD, Yuan JM, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and incident type 2 diabetes: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(2):520–6. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.110.009357.

Djousse L, Gaziano JM, Buring JE, Lee IM. Dietary omega-3 fatty acids and fish consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(1):143–50. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.110.005603.

Margolis KL, Wei F, de Boer IH, Howard BV, Liu S, Manson JE, et al. A diet high in low-fat dairy products lowers diabetes risk in postmenopausal women. J Nutr. 2011;141(11):1969–74. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.111.143339.

Villegas R, Xiang YB, Elasy T, Li HL, Yang G, Cai H, et al. Fish, shellfish, and long-chain n-3 fatty acid consumption and risk of incident type 2 diabetes in middle-aged Chinese men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(2):543–51. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.111.013193.

Alhazmi A, Stojanovski E, McEvoy M, Garg ML. Macronutrient intake and type 2 diabetes risk in middle-aged Australian women. Results from the Australian longitudinal study on Women’s health. Public Health Nutr. 2014;17(7):1587–94. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980013001870.

Louie JC, Flood VM, Rangan AM, Burlutsky G, Gill TP, Gopinath B, et al. Higher regular fat dairy consumption is associated with lower incidence of metabolic syndrome but not type 2 diabetes. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;23(9):816–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2012.08.004.

Ericson U, Hellstrand S, Brunkwall L, Schulz CA, Sonestedt E, Wallstrom P, et al. Food sources of fat may clarify the inconsistent role of dietary fat intake for incidence of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(5):1065–80. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.103010.

Guasch-Ferre M, Hruby A, Salas-Salvado J, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Sun Q, Willett WC, et al. Olive oil consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes in US women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102(2):479–86. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.112029.

Guasch-Ferre M, Becerra-Tomas N, Ruiz-Canela M, Corella D, Schroder H, Estruch R, et al. Total and subtypes of dietary fat intake and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Prevencion con Dieta Mediterranea (PREDIMED) study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(3):723–35. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.116.142034.

Patel PS, Sharp SJ, Jansen E, Luben RN, Khaw KT, Wareham NJ, et al. Fatty acids measured in plasma and erythrocyte-membrane phospholipids and derived by food-frequency questionnaire and the risk of new-onset type 2 diabetes: a pilot study in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Norfolk cohort. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(5):1214–22. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2010.29182.

•• Mozaffarian D, Cao H, King IB, Lemaitre RN, Song X, Siscovick DS, et al. Trans-palmitoleic acid, metabolic risk factors, and new-onset diabetes in U.S. adults: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(12):790–9. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-153-12-201012210-00005 This analysis from the Cardiovascular Health Study investigated whether circulating trans-palmitoleic acid was independently related to lower metabloc risk and incident type 2 diabetes. The use of fatty acid biomarkers in combination with self-reported dietary data revealed a potentially unique role of dairy fat in reduced risk for type 2 diabetes.

Djousse L, Biggs ML, Lemaitre RN, King IB, Song X, Ix JH, et al. Plasma omega-3 fatty acids and incident diabetes in older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94(2):527–33. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.111.013334.

Mozaffarian D, de Oliveira Otto MC, Lemaitre RN, Fretts AM, Hotamisligil G, Tsai MY, et al. Trans-Palmitoleic acid, other dairy fat biomarkers, and incident diabetes: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(4):854–61. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.112.045468.

Mahendran Y, Cederberg H, Vangipurapu J, Kangas AJ, Soininen P, Kuusisto J, et al. Glycerol and fatty acids in serum predict the development of hyperglycemia and type 2 diabetes in Finnish men. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(11):3732–8. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-0800.

Santaren ID, Watkins SM, Liese AD, Wagenknecht LE, Rewers MJ, Haffner SM, et al. Serum pentadecanoic acid (15:0), a short-term marker of dairy food intake, is inversely associated with incident type 2 diabetes and its underlying disorders. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(6):1532–40. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.092544.

Mahendran Y, Agren J, Uusitupa M, Cederberg H, Vangipurapu J, Stancakova A, et al. Association of erythrocyte membrane fatty acids with changes in glycemia and risk of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(1):79–85. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.113.069740.

Virtanen JK, Mursu J, Voutilainen S, Uusitupa M, Tuomainen TP. Serum omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and risk of incident type 2 diabetes in men: the Kuopio ischemic heart disease risk factor study. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(1):189–96. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc13-1504.

Lemaitre RN, Fretts AM, Sitlani CM, Biggs ML, Mukamal K, King IB, et al. Plasma phospholipid very-long-chain saturated fatty acids and incident diabetes in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(5):1047–54. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.101857.

Ma W, Wu JH, Wang Q, Lemaitre RN, Mukamal KJ, Djousse L, et al. Prospective association of fatty acids in the de novo lipogenesis pathway with risk of type 2 diabetes: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(1):153–63. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.092601.

Lankinen MA, Stancakova A, Uusitupa M, Agren J, Pihlajamaki J, Kuusisto J, et al. Plasma fatty acids as predictors of glycaemia and type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2015;58(11):2533–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-015-3730-5.

Steffen BT, Steffen LM, Zhou X, Ouyang P, Weir NL, Tsai MY. n-3 Fatty acids attenuate the risk of diabetes associated with elevated serum nonesterified fatty acids: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(4):575–80. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc14-1919.

Takkunen MJ, Schwab US, de Mello VD, Eriksson JG, Lindstrom J, Tuomilehto J, et al. Longitudinal associations of serum fatty acid composition with type 2 diabetes risk and markers of insulin secretion and sensitivity in the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Eur J Nutr. 2016;55(3):967–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-015-0911-4.

Yakoob MY, Shi P, Willett WC, Rexrode KM, Campos H, Orav EJ, et al. Circulating biomarkers of dairy fat and risk of incident diabetes mellitus among men and women in the United States in two large prospective cohorts. Circulation. 2016;133(17):1645–54. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018410.

Yary T, Voutilainen S, Tuomainen TP, Ruusunen A, Nurmi T, Virtanen JK. Serum n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids, Delta5- and Delta6-desaturase activities, and risk of incident type 2 diabetes in men: the Kuopio Ischaemic Heart Disease Risk Factor Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(5):1337–43. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.128629.

Howard BV, Aragaki AK, Tinker LF, Allison M, Hingle MD, Johnson KC, et al. A low-fat dietary pattern and diabetes: a secondary analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative dietary modification trial. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(4):680–7. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc17-0534.

United States. Department of Health and Human Services., United States. Department of Agriculture., United States. Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2015-2020. Eighth edition. ed. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2015.

de Souza RJ, Mente A, Maroleanu A, Cozma AI, Ha V, Kishibe T, et al. Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. BMJ. 2015;351:h3978. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h3978.

Mozaffarian D, Cao H, King IB, Lemaitre RN, Song X, Siscovick DS, et al. Circulating palmitoleic acid and risk of metabolic abnormalities and new-onset diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(6):1350–8. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.110.003970.

• Ratnayake WM. Concerns about the use of 15:0, 17:0, and trans-16:1n-7 as biomarkers of dairy fat intake in recent observational studies that suggest beneficial effects of dairy food on incidence of diabetes and stroke. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(5):1102–3. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.105379 This Letter to the Editor eloquently outlines the potential pitfalls of relying too heavily on biomarker data to draw definitive conclusions about diet and health. It is an important commentary that can be extrapolated to much of the literature in nutrition research.

Due A, Larsen TM, Mu H, Hermansen K, Stender S, Astrup A. Comparison of 3 ad libitum diets for weight-loss maintenance, risk of cardiovascular disease, and diabetes: a 6-mo randomized, controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(5):1232–41. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2007.25695.

Gadgil MD, Appel LJ, Yeung E, Anderson CA, Sacks FM, Miller ER 3rd. The effects of carbohydrate, unsaturated fat, and protein intake on measures of insulin sensitivity: results from the OmniHeart trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(5):1132–7. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc12-0869.

Tinker LF, Bonds DE, Margolis KL, Manson JE, Howard BV, Larson J, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of treated diabetes mellitus in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled dietary modification trial. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(14):1500–11. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.168.14.1500.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Beth H. Rice Bradley declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Diabetes and Obesity

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rice Bradley, B.H. Dietary Fat and Risk for Type 2 Diabetes: a Review of Recent Research. Curr Nutr Rep 7, 214–226 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-018-0244-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-018-0244-z