Abstract

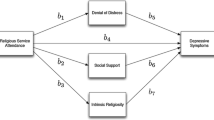

Turning to religion to seek its social benefits has been associated with poor psychological well-being. Researchers have concluded that endorsing this extrinsic and social orientation toward religion is inauthentic and unhealthy. However, few studies have focused on extrinsic-social religious orientation’s negative relationship with well-being, leaving open the possibility that their relationship is spurious. The present study argues that people endorsing an extrinsic-social religious orientation also perceive lower levels of social support in their lives, thus their turning to religion to fill this social void. As social support is important for healthy psychological functioning, perceived social support may be the critical third variable explaining why extrinsic-social religious orientation appears to have psychological costs. This study supported our expectations among undergraduates in two countries: the United States (N = 156) and the Republic of Ireland (N = 255). There were negative bivariate associations between extrinsic-social religious orientation and both perceived social support and emotional well-being. Accounting for the effects of perceived social support, however, reduced the association between the extrinsic-social religious orientation and well-being to non-significance. Thus, people endorsing an extrinsic and social orientation toward religion tend to have poor well-being because they perceive less supportive relationships in their lives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Given that there is a long history of measuring extrinsic religiosity as a single factor, we used confirmatory factor analysis to test whether our approach of estimating two-factors (i.e., extrinsic-personal and extrinsic-social) rather than a single factor was justifiable empirically. In both the US and Republic of Ireland samples, we found that the two-factor model fit the data well, while the single factor model had unacceptable fit.

Four of the items in the Social Provisions Scale include the term “well-being.” For example, one such item asks participants whether they agree or disagree with the following statement: “I have close relationships that provide me with a sense of emotional security and well-being.” In order to ensure that these four items were not inflating the association between perceived social support and emotional well-being, we conducted analyses that mirror those presented in this paper with a reduced form of this scale omitting these four items. The pattern of results did not change substantively. We chose to use the full scale for the results presented in this paper as the full Social Provisions Scale has been widely used and validated.

References

Allport, Gordon W., and Michael J. Ross. 1967. Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 5: 432–443.

Baker, Mark, and Richard Gorsuch. 1982. Trait anxiety and intrinsic-extrinsic religiousness. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 21: 119–122.

Barrera Jr, Manuel. 1986. Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models. American Journal of Community Psychology 14: 413–445.

Bartz, Jeremy D., Scott P. Richards, Timothy B. Smith, and Lane Fischer. 2010. A 17-year longitudinal study of religion and mental health in a Mormon sample. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 13: 683–695.

Baumeister, Roy F., and Mark R. Leary. 1995. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin 117: 497.

Bergin, Allen E., Kevin S. Masters, and Scott P. Richards. 1987. Religiousness and mental health reconsidered: A study of an intrinsically religious sample. Journal of Counseling Psychology 34: 197–204.

Brewczynski, Jacek, and Douglas A. MacDonald. 2006. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Allport and Ross Religious Orientation Scale with a polish sample. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 16: 63–76.

Cohen, Sheldon. 2004. Social relationships and health. American Psychologist 59: 676–684.

Cohen, Adam B., Daniel E. Hall, Harold G. Koenig, and Keith G. Meador. 2005. Social versus individual motivation: Implications for normative definitions of religious orientation. Personality and Social Psychology Review 9: 48–61.

Cutrona, Carolyn E., and Daniel W. Russell. 1987. The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. In Advances in personal relationships, ed. Warren H. Jones, and Daniel Perlman. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Donahue, Michael J. 1985. Intrinsic and extrinsic religiousness: Review and meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 48: 400–419.

Elliott, Marta. 2001. Gender differences in causes of depression. Women and Health 33: 163–177.

Ellison, Christopher G., and Jeffrey S. Levin. 1998. The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory and future directions. Health Education and Behavior 25: 700–720.

Fiala, William E., Jeffrey P. Bjorck, and Richard Gorsuch. 2002. The Religious Support Scale: Construction, validation and cross-validation. American Journal of Community Psychology 30: 761–786.

Flere, Sergej, and Miran Lavrič. 2008. Is intrinsic religious orientation a culturally specific American Protestant concept? The fusion of intrinsic and extrinsic religious orientation among non-Protestants. European Journal of Social Psychology 38: 521–530.

Francis, Leslie J. 2007. Introducing the new indices of religious orientation (NIRO): Conceptualization and measurement. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 10: 585–602.

Gorsuch, Richard L., and Susan E. McPherson. 1989. Intrinsic/extrinsic measurement: I/E-revised and Single-Item Scales. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 28: 348–354.

Gorsuch, Richard L., and Daniel G. Venable. 1983. Development of an ‘age universal’ I–E Scale. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 22: 181–187.

Hill, Peter C., and Ralph W. Hood Jr. 1999. Measures of religiosity. Birmingham, AL: Religious Education Press.

Hill, Peter C., and Kenneth I. Pargament. 2008. Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of religion and spirituality: Implications for physical and mental health research. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality S: 3–17.

Holt, Cheryl L., Min Qi Wang, Eddie M. Clark, Beverly Rosa Williams, and Emily Schulz. 2013. Religious involvement and physical and emotional functioning among African Americans: The mediating role of religious support. Psychology and Health 28: 267–283.

Hood Jr, Ralph W., Peter C. Hill, and Bernard Spilka. 2009. The psychology of religion: An empirical approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hunt, Richard A., and Morton King. 1971. The intrinsic-extrinsic concept: A review and evaluation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 10: 339–356.

Kirkpatrick, Lee A. 1989. A psychometric analysis of the Allport-Ross and Feagin measures of intrinsic-extrinsic religious orientation. In Research in the social scientific study of religion: A research annual, ed. Monty L. Lynn, and David O. Moberg. Greenwich, CT: Elsevier Science/JAI Press.

Kirkpatrick, Lee A., and Ralph W. Hood Jr. 1990. Intrinsic-extrinsic religious orientation: The boon or bane of contemporary psychology of religion? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 29: 442–462.

Krause, Neal. 2006. Exploring the stress-buffering effects of church-based and secular social support on self-rated health in late life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences 61B: S35–S43.

Krause, Neal. 2008. The social foundations of religious meaning in life. Research on Aging 30: 395–427.

Krause, Neal. 2011. Stress, religious-based coping, and physical health. In Toward a sociological theory of religion and health, ed. Anthony J. Blasi. Netherlands: Brill.

Leong, Frederick T.L., and Peter Zachar. 1990. An evaluation of Allport’s Religious Orientation Scale across one Australian and two United States samples. Educational and Psychological Measurement 50: 359–368.

Lim, Chaeyoon, and Robert D. Putnam. 2010. Religion, social networks, and life satisfaction. American Sociological Review 75: 914–933.

Liu, Chung-Chu. 2010. The relationship between personal religious orientation and emotional intelligence. Social Behavior and Personality 38: 461–468.

Maltby, John. 2005. Protecting the sacred and expressions of rituality: Examining the relationship between extrinsic dimensions of religiosity and unhealthy guilt. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 78: 77–93.

Maltby, John, and Liza Day. 2003. Religious orientation, religious coping and appraisals of stress: Assessing primary appraisal factors in the relationship between religiosity and psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences 34: 1209–1224.

Masters, Kevin S., and Allen E. Bergin. 1992. Religious orientation and mental health. In Religion and mental health, ed. John F. Schumaker. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Mirowsky, John, and Catherine E. Ross. 1992. Age and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 33: 187–205.

Nielsen, Michael E., and Ryan T. Cragun. 2010. Religious orientation, religious affiliation and boundary maintenance: The case of polygamy. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 13: 761–770.

Pollard, Lawanda J., and Larry W. Bates. 2004. Religion and perceived stress among undergraduates during Fall 2001 final examinations. Psychological Reports 95: 999–1007.

Pössel, Patrick, Nina C. Martin, Judy Garber, Aaron W. Banister, Natalie K. Pickering, and Martin Hautzinger. 2010. Bidirectional relations of religious orientation and depressive symptoms in adolescents: A short-term longitudinal study. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 3: 24–38.

Prati, Gabriele, and Luca Pietrantoni. 2010. The relation of perceived and received social support to mental health among first responders: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Community Psychology 38: 403–417.

Reinhardt, Joanne P., Kathrin Boerner, and Amy Horowitz. 2006. Good to have but not to use: Differential impact of perceived and received support on well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 23: 117–129.

Reis, Harry T., and Andrew W. Collins. 2004. Relationships, human behavior and psychological science. Current Directions in Psychological Science 13: 233–237.

Salsman, John M., Tamara L. Brown, Emily H. Brechting, and Charles R. Carlson. 2005. The link between religion and spirituality and psychological adjustment: The mediating role of optimism and social support. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 31: 522–535.

Simon, Robin W. 2002. Revisiting the relationships among gender, marital status and mental health. American Journal of Sociology 107: 1065–1096.

Smith, Timothy B., Michael E. McCullough, and Justin Poll. 2003. Religiousness and depression: Evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin 129: 614–636.

Tapanya, Sombat, Richard Nicki, and Ousa Jarusawad. 1997. Worry and intrinsic/extrinsic religious orientation among Buddhist (Thai) and Christian (Canadian) elderly persons. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development 44: 73–83.

Ware Jr, John E., and Barbara Gandek. 1998. Overview of the SF-36 health survey and the international quality of life assessment (IQOLA) project. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 51: 903–912.

Ware Jr, John E., and Cathy D. Sherbourne. 1992. The MOS 36-item short-form health SURVEY (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care 30: 473–483.

Watson, P.J., Ralph W. Hood Jr, Ronald J. Morris, and James R. Hall. 1984. Empathy, religious orientation and social desirability. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied 117: 211–216.

Watson, P.J., Ronald J. Morris, and Ralph W. Hood Jr. 1990. Extrinsic scale factors: Correlations and construction of religious orientation types. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 9: 35–46.

Weiss, Robert S. 1974. The provisions of social relationships. In Doing unto others, ed. Zick Rubin. Eaglewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Williamson, Paul W., Ralph W. Hood Jr, Aneeq Ahmad, Mahmood Sadiq, and Peter C. Hill. 2010. The Intratextual Fundamentalism Scale: Cross-cultural application, validity evidence and relationship with religious orientation and the Big 5 factor markers. Mental Health, Religion and Culture 13: 721–747.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by funding from Hobart and William Smith Colleges’ Charles H. Salisbury Jr. Endowed Internship Award. We would like to acknowledge our appreciation for the assistance provided by Drs. Brian M. Hughes and Siobhán Howard.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Doane, M.J., Elliott, M. & Dyrenforth, P.S. Extrinsic Religious Orientation and Well-Being: Is Their Negative Association Real or Spurious?. Rev Relig Res 56, 45–60 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-013-0137-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-013-0137-y