Abstract

Key message

We evaluated the use of low-density airborne laser scanning data to estimate diameter distributions in radiata pine plantations. The moment-based parameter recovery method was used to estimate the diameter distributions, considering LiDAR metrics as explanatory variables. The fitted models explained more than 77% of the observed variability. This approach can be replicated every 6 years (temporal cover planned for countrywide LiDAR flights in Spain).

Context

The estimation of stand diameter distribution is informative for forest managers in terms of stand structure, forest growth model inputs, and economic timber value. In this sense, airborne LiDAR may represent an adequate source of information.

Aims

The objective was to evaluate the use of low-density Spanish countrywide LiDAR data for estimating diameter distributions in Pinus radiata D. Don stands in NW Spain.

Methods

The empirical distributions were obtained from 25 sample plots. We applied the moment-based parameter recovery method in combination with the Weibull function to estimate the diameter distributions, considering LiDAR metrics as explanatory variables. We evaluated the results by using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test and a classification tree and random forest (RF) to relate the KS test result for each plot to stand-level variables.

Results

The models used to estimate average (dm) and quadratic (dg) mean diameters from LiDAR metrics, required for recovery of the Weibull parameters, explained a high percentage of the observed variance (77 and 80%, respectively), with RMSE values of 3.626 and 3.422 cm for the same variables. However, the proportion of plots accepted by the KS was low. This poor performance may be due to the strictness of the KS test and/or by the characteristics of the LiDAR flight.

Conclusion

The results justify the assessment of this approach over different species and forest types in regional or countrywide surveys.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Diameter at breast height (DBH, 1.3 m above ground level) is the explanatory variable most commonly used in single- and multiple-entry equations to predict tree-level attributes, mainly because it is easy to measure in the field and is strongly related to many forest variables (Burkhart and Tomé 2012). The empirical diameter distribution (specified by the DBH measurements within the stand) is one of the most descriptive and important characteristics for forest managers because it provides information about stand structure and inputs for forest growth models and enables economic assessment of timber value and development of management schedules (Bollandsås and Næsset 2007; Kangas et al. 2007; Pascual et al. 2013).

Diameter distributions can be represented using a discrete density (or frequency) histogram, a continuous probability density function (PDF) (or the equivalent cumulative distribution), or a list of quantiles or percentiles. In forestry practice, DBH measurements are not always available, and the diameter distribution must therefore be predicted by using stand attributes as explanatory variables (e.g., density, site index, age, mean tree size), usually under the assumption that it follows a specified theoretical PDF (Liu et al. 2004; Maltamo and Gobakken 2014). Although numerous PDFs have been used to describe unimodal diameter distributions (e.g., Charlier, Normal, Log-normal, Exponential, Beta, Gamma, Pearl-Reed, SB Johnson, Weibull), the Weibull function is the most frequently used for managed, even-aged stands (e.g., Poudel and Cao 2013). Specifically, the two-parameter formulation of the Weibull function has proven simple to use, yet flexible enough to describe different shapes of unimodal distributions (e.g., Maltamo et al. 1995; Gorgoso et al. 2007).

Two parametric methods are available for predicting diameter distributions from field-derived stand variables: (i) the parameter prediction method (PPM), which directly models the PDF parameters as a function of stand variables, and (ii) the parameter recovery method (PRM), which recovers the PDF parameters from moments (moment-based PRM) or percentiles (percentile-based PRM) of the diameter distribution, which are expressed as functions of stand-level attributes (Hyink and Moser 1983). The moment-based PRM is usually preferred because it guarantees that the sum of the disaggregated stem density and basal area obtained by the Weibull function equals the stand stem density and stand basal area, respectively, resulting in numerical compatibility (e.g., Hyink and Moser 1983; Siipilehto and Mehtätalo 2013).

In the last 20 years, airborne LiDAR has been increasingly used for forest inventories at different scales (Yu et al. 2011), because of its capacity to provide spatially explicit detailed three-dimensional information about the size and structure of the forest canopy over entire areas (Reitberger et al. 2008; Wagner et al. 2008). Canopy cover and tree height are the variables most closely related to LiDAR data, as LiDAR data is mainly affected by the vertical distribution of the canopy layers (Maltamo and Gobakken 2014). However, LiDAR metrics are also related to characteristics of the diameter distributions (Maltamo and Gobakken 2014).

Three approaches have been considered for estimating the diameter distribution from LiDAR data, within the framework of parametric prediction (Maltamo and Gobakken 2014). The first uses regression analysis to directly relate LiDAR metrics to the PDF parameters (e.g., Breidenbach et al. 2008; Thomas et al. 2008) or the moments or percentiles of the diameter distribution, which are then used to recover the PDF parameters (e.g., Gobakken and Næsset 2004, 2005; Bollandsås and Næsset 2007). The second approach considers modeling the PDF parameters from stand-level variables predicted using area-based LiDAR metrics (e.g., Maltamo et al. 2006, 2007; Holopainen et al. 2010). It requires two equations: one to relate the stand variables to LiDAR metrics and another to relate the PDF parameters to the estimated stand variables, implying model error accumulation and cross-correlated residuals. The third approach predicts the diameter distribution on the basis of recognition of individual trees (Hyyppä and Inkinen 1999; Persson et al. 2002; Villikka et al. 2007), which requires high pulse densities (usually more than 5 pulses m−2: Bollandsås and Næsset 2007). In this case, only the dominant tree layer is usually detected (Næsset et al. 2004); for the tallest trees, the DBH for a given height is more variable and the relationship between DBH and height is weaker (Maltamo et al. 2004) and affected by site factors (Maltamo and Gobakken 2014). Because the first approach does not have any of the above disadvantages, and as Peuhkurinen et al. (2011) have demonstrated its superiority for predicting diameter distributions in even-aged stands, we selected this approach for use in the present study.

We aimed to predict the diameter distributions in Pinus radiata D. Don plantations in Galicia (NW Spain) by using height and canopy cover LiDAR metrics from a small-footprint, discrete-return system. For this purpose, we used the moment-based PRM in combination with the two-parameter Weibull function. LiDAR metrics were obtained from low-density LiDAR data provided by the Spanish countrywide PNOA (Plan Nacional de Ortografía Aérea, www.pnoa.ign.es) project.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Study area and data

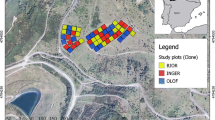

The study was conducted over the main distribution area of P. radiata in Galicia (NW Spain), i.e., the province of Lugo (Fig. 1). The forests under study are representative of P. radiata stands in NW Spain and are thus mainly characterized by high planting-density, low-intensity silvicultural treatments and the presence of moderate shrub fuel loads (Castedo-Dorado et al. 2012).

The field data used for modeling the diameter distributions were obtained from two different sources. The first source (A) comprises a network of 10 rectangular plots (600 to 1000 m2 in size, depending on stand density) established for growth modeling purposes. The inventory design was thus focused on obtaining an adequate representation of the existing range of ages, stem densities, and site indices (for details, see Castedo-Dorado et al. 2007). The second source (B) comprises 15 rectangular plots (1000 m2 in size) established for assessing the influence of thinning treatments in crown fire potential. The inventory design was deliberately focused on representing young and highly stocked stands, as these are usually fire prone (see Gómez-Vázquez et al. 2013, for details). Although both networks of plots cover a larger area, only the abovementioned 25 plots were selected for this study because they were re-measured close to the PNOA LiDAR flight date.

For all plots, DBH and total tree height were measured in all trees with a caliper and a Vertex III hypsometer, respectively. In addition, the UTM coordinates of the four corners of each plot were obtained from topographic surveys by using a total station and a differential GPS.

The following stand variables were calculated for each plot: stand density (N, stems ha−1), stand basal area (G, m2 ha−1), average height (Hm, m), dominant height (H, m, defined as the average height of the 100 largest-DBH trees per hectare), site index (S, defined as the dominant height at a reference age of 20 years, using the height growth model developed by Diéguez-Aranda et al. 2005), arithmetic mean diameter (dm, cm), and quadratic mean diameter (dg, cm). Stand age (t, years) was determined from the plantation date. Additionally, the empirical diameter distribution was obtained for each plot from field measurements, as well as the empirical weighted distributions for tree basal area (g-weighted) and tree volume (v-weighted). While g was calculated straightforwardly from the diameter measurements, tree volume had to be estimated from the diameter by predicting height with a height–diameter model (Castedo Dorado et al. 2006) and subsequently estimating the volume with a stem taper function (Diéguez-Aranda et al. 2009).

Table 1 shows the summary statistics of the tree and stand variables. Figure 2 shows a scatter plot matrix for the variables t, N, H, and S, which reveals that field data cover the entire duration of stand development, considering the rotations usually applied to this species in Galicia (on average around 25 years in private forests; Rodríguez et al. 2002).

LiDAR data were acquired for the PNOA project under the direction of the Spanish Ministry of Development (Dirección General del Instituto Geográfico Nacional and Centro Nacional de Información Geográfica), between 5 September and 29 October 2009, with an RIEGL LMS-Q680 sensor, operated at 1064 nm, pulse repetition rate of 70 kHz, scan frequency of 46 Hz, maximum scan angle of ± 30°, and average flying height of 1300 m above sea level. A maximum of 4 returns per pulse were registered, with a theoretical laser pulse density required for the PNOA project of 0.5 first returns per square meter. Summary statistics of the LiDAR return density per square meter within the plots are shown in Table 1.

2.2 Extraction of LiDAR metrics

We used FUSION V. 3.50 software (McGaughey 2015) to filter and interpolate the data and generate the digital elevation model (DEM) and normalized height of the LiDAR data cloud (NHD). We used LiDAR data within the limits of the 25 field plots to calculate metrics related to the height distribution and canopy closure using the returns from above 1 m, following the steps described in González-Ferreiro et al. (2017) (see Table 2 for details of the LiDAR-derived metrics).

2.3 Method of moments for recovery of Weibull parameters

The PDF of the two-parameter Weibull, considering x as a continuous random variable, is expressed as follows (Bailey and Dell 1973):

where, the f(x) value represents the density function for x, b is a scale parameter, and c is a shape parameter.

In the method of moments, the parameters of the Weibull density function are recovered from the first two moments of the diameter distribution: arithmetic mean diameter (dm) and diameter variance (σd2) (Newby 1980; Burk and Newberry 1984). Thus, the following expressions were used to recover parameters b and c:

where dg is related to the second moment of the diameter distribution through the expression

and Γ(i) is the Gamma function for i, where i is the variable on which the function depends.

When using stand-level field inventory data, the recovery procedure relies on dm being estimated from dg and other stand-level attributes (e.g., t, N, H, S); dg, in turn, can be directly calculated from G and N. Within the LiDAR data framework, these stand-level variables can be replaced by LiDAR metrics as explanatory variables to estimate dg and dm. Once these variables are estimated, parameters b and c can be obtained by solving the system of Eqs. 2 and 3.

We have also considered another option whereby parameters b and dg were modeled through LiDAR metrics, and parameter c was then recovered. However, as poorer results were obtained than with the abovementioned methodology, this option was ruled out for further analyses.

2.4 Regression models

We used a linear model to establish the empirical relationship between dg and LiDAR metrics:

where X1, X2, …, Xn are potential explanatory variables related to the LiDAR-derived height distribution and canopy closure (Table 2); α0, α1, …, αn are the parameters to be estimated in the fitting process; and ε is the additive error term, which is assumed to be independent and normally and identically distributed with zero mean.

For a given stand, dm is always smaller than or equal to dg, and we therefore used the following model expression to take this restriction into account (Frazier 1981):

Finally, we applied a natural logarithmic transformation to Eq. 6 to linearize the model and facilitate selection of the independent variables:

where Y1, Y2, …, Ym are potential explanatory variables related to the LiDAR-derived height distribution and canopy closure (Table 2); β0, β1, …, βm are the parameters, and ε as aforementioned.

2.5 Model fitting and selection

In the first step, we applied the stepwise selection procedure to select the best subset of independent variables to be included in Eqs. 5 and 7. We used a combination of forward and backward algorithms for variable selection implemented in the regsubsets function, of the leaps package (Lumley and Miller 2017) of the R statistical software (R Core Team 2016). We selected those models with the lowest values of the Bayesian information criterion (BIC: Schwarz 1978), with no problems related to multicollinearity between explanatory variables (i.e., those with a condition index below 30; Belsley 1991) and with all parameter estimates significant at the 5% level.

In the second step, we fitted the system of two equations (Eqs. 5 and 6), considering LiDAR metrics selected in the first step as exogenous variables (i.e., obtained outside the system) and dm and dg as endogenous variables (i.e., variables that the model is intended to predict; Borders 1989). As the endogenous variable dg occurs on both sides of the equations, cross-equation correlation between error components is expected. Therefore, biased and inconsistent parameter estimations would be obtained using the ordinary least-squares technique (Borders and Bailey 1986; Borders 1989). Accordingly, the system of equations was fitted simultaneously by a three-stage least-squares method (3SLS: Zellner and Theil 1962), which combines two-stage least squares (2SLS) with seemingly unrelated regression (SUR), taking the cross-equation error correlations into account. For this purpose, we used the nlsystemfit function of the systemfit package (Henningsen and Hamann 2007) of R (R Core Team 2016). We used the coefficient of determination (R2) and the root mean square error (RMSE) to evaluate the goodness of fit of the models.

2.6 Accuracy assessment

We applied the Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test, which compares theoretical and empirical (field-observed) diameter distributions, to assess the suitability of the two-parameter Weibull function for predicting the diameter distribution from the moment-based PRM and LiDAR metrics. As the diameter distribution parameters are estimated from empirical information (LiDAR data), the estimated distribution is not theoretical. For this case, Lilliefors (1967) stated that the KS statistic existing distribution is no longer valid and should be obtained by Monte Carlo simulation. Therefore, for each plot, we generated 10,000 independent identically distributed pseudo-random samples under the null hypothesis: we used the rweibull function of R (R Core Team 2016) to generate random samples with a size equal to the number of observations of the corresponding plot, and with recovered parameters (from field or from LiDAR information), computing then the KS statistic for each sample. This subsequently enabled estimation of the distribution of the KS statistic under the null hypothesis for each plot. If the KS statistic value obtained from the comparison between the estimated and empirical distribution of a plot exceeds the critical value at a specified significance level (obtained from the approximated distribution of the KS statistic), the hypothesis that the observations belong to a Weibull distribution of the specified parameters should be rejected. The significance level was established at 5%.

In addition, the performance of the methodology was also evaluated on the basis of numerical and graphical analyses. We used the former type of analysis to assess the RMSE obtained for prediction of DBH, G, and V from predicted diameter distributions (from field variables and LiDAR metrics). The predicted variables were obtained using the following procedures: (1) for DBH, we predicted the diameter values of a plot by applying the inverse of the diameter distribution function (i.e., the quantile function) over the empirical distribution function values; (2) for G, we integrated the diameter density function multiplied by squared diameter (to obtain the expected value of quadratic mean diameter), subsequently obtaining G by direct calculation from dg and N; and (3) for V, we integrated the diameter density function multiplied by the tree volume of the corresponding diameter, scaled by the number of trees per hectare. For graphical analysis, we plotted the unweighted and weighted predicted diameter distributions (from field and LiDAR variables) against the empirical diameter distributions, for visual assessment of the prediction accuracy.

2.7 KS acceptance/rejection prediction

After applying the KS test and comparing the estimated unweighted and weighted distributions with the empirical distributions, we used a classification tree to relate the result of the KS test for each plot (null hypothesis accepted or rejected) with the measured stand-level attributes N, G, H, V, S, t, dm, and dg. The aim of this analysis is to search for common properties in accepted and rejected plots. If any patterns are observed, they could be used in field data stratification, thus increasing the efficiency of the diameter distribution modeling approach (e.g., Thomas et al. 2008).

Moreover, we used the random forest (RF) approach to examine the influence of stand variables on the suitability of the two-parameter Weibull PDF for characterizing the empirical diameter distribution. The relevance of each stand variable in RF was calculated by analyzing the changes in the classification error when the values of the variable are randomly permuted; if the effect is large, the variable is assigned greater importance (Reif et al. 2006). We implemented the classification tree analyses and RF using the R software packages rpart (Therneau et al. 2017) and randomForest (Liaw and Wiener 2002) (R Core Team 2016).

Data availability

LiDAR data is freely available at http://mapas.xunta.gal/visores/descargas/ and http://centrodedescargas.cnig.es/CentroDescargas/buscadorCatalogo.do?codFamilia=LIDAR. Field datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to authors are still using them in other research activities, but they are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

3 Results

Table 3 summarizes the parameter estimates and goodness-of-fit statistics of the simultaneous fitting of the system of Eqs. 5 and 6. Note that in Eq. 5, the intercept was not included because it was not significant at a 95% confidence level. The fitted models explained 80 and 77% of the observed variability in dg and dm, respectively, with RMSE values of 3.422 and 3.626 cm for the same variables.

Table 4 shows the plots with diameter distribution adequately estimated according to the KS test results. The percentage of plots in which the null hypothesis was accepted (i.e., the estimated distribution is equal to the empirical distribution) varied between 28 and 40% (7, 9, and 10 plots for the unweighted, g-weighted, and v-weighted distributions, respectively; see Table 4) when we used LiDAR data to estimate dg and dm, subsequently recovering the distribution parameters. In six plots, the null hypothesis was accepted for all unweighted and weighted diameter distributions estimated from LiDAR data, while it was rejected for all cases in 14 plots. Comparatively, the percentage of acceptance increased up to 96–100% when we used field data (i.e., real values of dg and dm) in the parameter recovery process (the only case of rejection was plot number 8 for the unweighted diameter distributions).

Figure 3 shows the v-weighted observed cumulative relative frequency of each plot and the corresponding estimated distributions obtained from parameters recovered using field data (real information) and LiDAR data (the corresponding graphs for the unweighted and g-weighted distributions are included in Supplementary Figure 1a and b, respectively). We can observe that the empirical distribution is adequately described for the six plots that passed the KS test in all cases (see Table 4). On the other hand, the 14 plots where null hypothesis was always rejected usually display bias at a coarse scale.

Plots of cumulative relative frequencies against diameter at breast height (DBH) for v-weighted diameter distributions. The continuous lines represent field measurements (empirical distribution); the dashed lines represent the diameter distribution function estimated from field data; and the filled dots represent the diameter distribution function estimated from LiDAR data

Comparison between empirical distributions and the estimated diameter distributions using LiDAR metrics as predictors revealed RMSE values of 10.85 and 96.93 m3 ha−1 for the g- and v-weighted distributions, respectively. However, RMSE values < 0.001 and 17.36 m3 ha−1 were obtained directly from estimation from the field data for the same weighted distributions.

Because the best results of the KS test were obtained for the estimated v-weighted distributions, the classification tree was fitted for the groups obtained for these diameter distributions (15 plots were rejected and 10 plots were accepted). The results showed that H was the only predictor with a threshold of 22.6 m. Sample plots with values of H equal to or higher than 22.6 m were considered accepted by the KS test; otherwise, they were considered rejected. Application of this threshold yielded correct classification of 84% of the sample plots. These results are consistent with those obtained with the RF approach, in which the two most important stand variables were dominant height (H) and stand density (N).

4 Discussion

Many countries throughout the world have completed countrywide airborne LiDAR surveys in recent years (e.g., Denmark, Kortforsyningen; Finland, National Land Survey of Finland; Netherlands, Actueel Hoogte Bestand Nederland; Slovenia, Slovenian Environment Agency; Spain, Instituto Geográfico Nacional; Switzerland, Federal Office of Topography), with the main aim of producing high-resolution terrain maps (Ahokas et al. 2005). However, the flight parameters used in these surveys are not usually considered as optimal for quantifying natural resources, since low density, high flight height, and large scan angle are used in order to reduce the associated costs (González-Ferreiro et al. 2014). Nevertheless, this type of data has also proven useful for forest inventories (e.g., Villikka et al. 2012), practical forest management (e.g., Valbuena et al. 2016), and ecological applications (e.g., Vihervaara et al. 2015), among others.

In Spain, the low-density LiDAR data obtained in the PNOA project have proved useful for assessing numerous forest variables such as stand volume (Guerra-Hernández et al. 2016b), stand basal area (Guerra-Hernández et al. 2016b), Lorey’s mean height (González-Ferreiro et al. 2014; Guerra-Hernández et al. 2016b), canopy fuel variables (González-Ferreiro et al. 2014, 2017), fire severity (Montealegre et al. 2014), and biomass (Guerra-Hernández et al. 2016a, b). However, LiDAR data have not yet been used to estimate diameter distributions.

In this study, we first had to model dg and dm from LiDAR metrics, as these variables are needed to recover the parameters of the two-parameter Weibull function. The goodness-of-fit statistics obtained in the fitting phase were similar to others reported in the international literature. For example, for German forests dominated by Picea abies (L.) Karst., Breidenbach et al. (2008) used data from a 0.44 pulse m−2 LiDAR flight and reported an RMSE of 2.44 cm for dm, while Treitz et al. (2012) studied a broad range of forest types (coniferous and hardwoods) and conditions across Ontario by using artificially reduced LiDAR database of 0.5 pulses m−2 and reported RMSE values ranging from 0.76 to 4.3 cm for dg.

Conversely, the comparison between the estimated and the observed diameter distributions provided less satisfactory results, as the null hypothesis was accepted in only 40% of the plots. There are two possible explanations for these poor results: the use of the KS test for accuracy assessment and the characteristics of the countrywide PNOA LiDAR flight. Concerning the first possibility, most studies that have modeled diameter distributions from LiDAR data have reported the standard deviation of the differences between estimated and empirical values (e.g., Gobakken and Næsset 2004) rather than the KS test results. In this sense, Magnussen and Renaud (2016) used multidimensional scaling to estimate diameter distribution and considered differences less than 2.70 cm in diameter estimation as not relevant for practical applications, downplaying rejection rates in the KS test. In the present study, computation of the differences between estimated and empirical values revealed that the mean error for individual tree diameter estimations was 3.37 cm for the unweighted distribution predicted from LiDAR data. This error appears acceptable, considering the precision obtained from field measurements with, e.g., the laser relascope (up to 1.6 cm, Kalliovirta et al. 2005) or a laser dendrometer (up to 0.9 cm, Parker and Matney 1999). Although these errors are proportionally smaller than those reported in the present study, field-measured diameters are usually obtained from a small number of sample plots, and larger errors are expected in the extrapolation process, while LiDAR data allows complete coverage of the area of interest. Concerning the countrywide PNOA LiDAR data used, the acquisition flight was not specifically designed for forest inventory purposes (scanning angles of up to 30°, low-density data of 0.5 first returns m−2, and high average flying height of 1300 masl). According to White et al. (2013), a minimum of 1 pulse m−2 (> 4 pulses m−2 for dense forests on complex terrain) is recommended to produce an operational LiDAR-based enhanced forest inventory. Other possible explanations could be related to the lack of silvicultural treatments and with the morphology of radiata pine. P. radiata is a shade-intolerant conifer species and has a much lower crown morphological plasticity in relation to light availability than other more shade-tolerant species such as spruce (Parent and Messier 1995), which means that the plastic changes in the canopy dimensions do not follow a regular pattern of growth and this species is less efficient in covering the open holes in the canopy. This could have some implications in area-based approaches, especially when using very low LiDAR density.

Regarding the possible alternatives to the parametric PRM, non-parametric approaches such as the k-nearest neighbor method and RF regression have yielded satisfactory results for predicting diameter distributions in some area-based LiDAR studies (Packalén and Maltamo 2008; Maltamo et al. 2009; Shang et al. 2017). Nevertheless, the relatively small number of sample plots used in the present study may have led to overfitting, which could negatively affect the predictive performance of the models (Hawkins 2004; Zaffalon 2005).

According to the KS test, the best performance was achieved with g- and v-weighted diameter distributions, which gave greater weighting to larger and more valuable trees. This is consistent with the findings of Gobakken and Næsset (2004), who reported that the results obtained for diameter density function weighted by g were better than those corresponding to the unweighted distribution.

Explanatory variables for dg were LRA1 and h75, while the unique explanatory variable for dm was h01. LiDAR variables are usually classified as height metrics expressing the central trend in LiDAR height distribution (e.g., hmean and hmode), height metrics expressing the dispersion of LiDAR height distribution (e.g., hSD, hVAR, hAAD, hIQ, hCV, hmax, hmin), height metrics expressing the shape of LiDAR height distribution (e.g., hSkw, hKurt), percentiles of the LiDAR height distribution (e.g., h01, h10…, h95, h99), and canopy cover metrics (e.g., PFRAhmean, PFRAhmode, PARAhmean, PARAhmode, PFRA2, LRA1, FRA1, CRR). The highest percentiles of the LiDAR height distribution are commonly included as explanatory variables in most of the models based on area-based approach, because they fairly describe the mean height or the dominant height, and these field variables have a large importance in the description of vertical structure of a forest stand. Canopy cover metrics perform well in modeling those forest variables related with forest density, like basal area, quadratic mean diameter, canopy cover, or number of trees per hectare; these field variables are important in the description of the horizontal structure of a forest stand. Thus, the presence of explanatory variables like LRA1 and h75 was expected. The inclusion of h01 is more difficult to explain, since it is one of the lowest percentiles of the LiDAR height distribution; nevertheless, Gobakken and Næsset (2004, 2005) also found strong relationships between the percentile of the first pulse laser canopy heights for 0% (m) and the logarithmic transformations of 93 and 24 percentile for diameter distribution modeling, in young and mature forests dominated by P. abies and Pinus sylvestris L.

Finally, the results of the classification tree and the RF approach indicated that dominant height may be a significant variable for field data stratification. It is remarkable that 84% of the sample plots with values of H equal to or higher than 22.6 m were accepted by the KS test which suggests that this methodology performs much better in mature forest stands of P. radiata. Nonetheless, these results should be considered with caution, due to the low number of plots available for this study. The validity of these results should be verified when new data become available.

5 Conclusion

This study describes and tests an approach for predicting diameter distributions from LiDAR information, applied to a set of 25 plots established in P. radiata plantations in Galicia (NW Spain). Given the interest of the species in Galicia (NW Spain), forest managers and practitioners could benefit from better knowledge of diameter distributions for use in practical forest applications. The approach used was based on the moment-based parameter recovery method and the two-parameter Weibull function. The results showed that only 28 to 40% of the diameter distributions were accurately predicted with this method, according to the KS test. However, this may be explained by the strictness of this statistical test and/or by the characteristics of the LiDAR flight, which was not specifically designed for forest inventories. Analysis of why the null hypothesis was accepted or rejected by a classification tree and random forest approach demonstrated the importance of dominant height. The approach described has the potential to be replicated in different species and forest types in regional or countrywide surveys, although a larger number of field inventory plots would be required. In this respect, contracts for new PNOA flights have already been tendered, and the temporal cover provided by these flights has been established at 6 years. This should encourage new research studies, given the growing interest in the use of the Spanish countrywide LiDAR dataset for performing repeated large-scale forest inventories in an economically viable way.

References

Ahokas E, Yu X, Oksanen J, Hyyppä J, Kaartinen H, Hyyppä H (2005) Optimization of the scanning angle for countrywide laser scanning. In: Vosselman G, Brenner C, Hyyppä J (eds) Laser scanning 2005. International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing (ISPRS), Enschede, pp 115–119

Bailey RL, Dell TR (1973) Quantifying diameter distributions with the Weibull function. For Sci 19:97–104

Belsley DA (1991) Conditioning diagnostics: collinearity and weak data in regression. John Wiley & Sons Inc, New York 396 pp

Bollandsås OM, Næsset E (2007) Estimating percentile-based diameter distributions in uneven-sized Norway spruce stands using airborne laser scanner data. Scand J Forest Res 22:33–47

Borders BE (1989) Systems of equations in forest stand modeling. For Sci 35:548–556

Borders BE, Bailey RL (1986) A compatible system of growth and yield equations for slash pine fitted with restricted three-stage least squares. For Sci 32:185–201

Breidenbach J, Gläser C, Schmidt M (2008) Estimation of diameter distributions by means of airborne laser scanner data. Can J For Res 38:1611–1620

Burk TE, Newberry JD (1984) Notes: a simple algorithm for moment-based recovery of Weibull distribution parameters. For Sci 30:329–332

Burkhart H, Tomé M (2012) Modeling forest trees and stands. Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin 458 pp

Castedo Dorado F, Diéguez-Aranda U, Barrio Anta M, Sánchez Rodríguez M, von Gadow K (2006) A generalized height–diameter model including random components for radiata pine plantations in northwestern Spain. For Ecol Manag 229:202–213

Castedo-Dorado F, Diéguez-Aranda U, Álvarez-González JG (2007) A growth model for Pinus radiata D. Don stands in north-western Spain. Ann For Sci 64:453–465

Castedo-Dorado F, Gómez-Vázquez I, Fernandes PM, Crecente-Campo F (2012) Shrub fuel characteristics estimated from overstory variables in NW Spain pine stands. For Ecol Manag 275:130–141

Diéguez-Aranda U, Burkhart HE, Rodríguez-Soalleiro R (2005) Modelling dominant height of radiata pine (Pinus radiata D. Don) plantations in north-western Spain. For Ecol Manag 215:271–284

Diéguez-Aranda U, Rojo Alboreca A, Castedo-Dorado F, Álvarez González JG, Barrio-Anta M, Crecente-Campo F, González-González JM, Pérez-Cruzado C, Rodríguez Soalleiro R, López-Sánchez CA, Balboa-Murias MA, Gorgoso Varela JJ, Sánchez Rodríguez F (2009). Herramientas selvícolas para la gestión forestal sostenible en Galicia. Xunta de Galicia.

Frazier JR (1981) Compatible whole-stand and diameter distribution models for loblolly pine plantations. Dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. 125 pp

Gobakken T, Næsset E (2004) Estimation of diameter and basal area distributions in coniferous forest by means of airborne laser scanner data. Scand J Forest Res 19:529–542

Gobakken T, Næsset E (2005) Weibull and percentile models for lidar-based estimation of basal area distribution. Scand J Forest Res 20:490–502

Gómez-Vázquez I, Crecente-Campo F, Diéguez-Aranda U, Castedo-Dorado F (2013) Modelling canopy fuel variables in Pinus pinaster Ait. and Pinus radiata D. Don stands in northwestern Spain. Ann For Sci 70:161–172

González-Ferreiro E, Diéguez-Aranda U, Crecente-Campo F, Barreiro-Fernández L, Miranda D, Castedo-Dorado F (2014) Modelling canopy fuel variables for Pinus radiata D. Don in NW Spain with low-density LiDAR data. Int J Wildland Fire 23:350–362

González-Ferreiro E, Arellano-Pérez S, Castedo-Dorado F, Hevia A, Vega JA, Vega-Nieva D, Álvarez-González JG, Ruiz-González AD (2017) Modelling the vertical distribution of canopy fuel load using national forest inventory and low-density airbone laser scanning data. PLoS One 12:e0176114

Gorgoso JJ, González JÁ, Rojo A, Grandas-Arias JA (2007) Modelling diameter distributions of Betula alba L. stands in northwest Spain with the two-parameter Weibull function. For Syst 16:113–123

Guerra-Hernández J, Bastos-Görgens E, García-Gutiérrez J, Estraviz-Rodriguez LC, Tomé M, González-Ferreiro E (2016a) Comparison of ALS based models for estimating aboveground biomass in three types of Mediterranean forest. Eur J Remote Sens 49:185–204

Guerra-Hernández J, Tomé M, González-Ferreiro E (2016b) Using low density LiDAR data to map Mediterranean forest characteristics by means of an area-based approach and height threshold analysis. Spanish J Remote Sens 46:103–117

Hawkins DM (2004) The problem of overfitting. J Chem Inf Comput Sci 44:1–12

Henningsen A, Hamann JD (2007) Systemfit: a package for estimating systems of simultaneous equations in R. J Stat Softw 23:1–40

Holopainen M, Vastaranta M, Rasinmäki J, Kalliovirta J, Mäkinen A, Haapanen R, Melkas T, Yu X, Hyyppä J (2010) Uncertainty in timber assortment estimates predicted from forest inventory data. Eur J For Res 129:1131–1142

Hyink DM, Moser JW (1983) A generalized framework for projecting forest yield and stand structure using diameter distributions. For Sci 29:85–95

Hyyppä J, Inkinen M (1999) Detecting and estimating attributes for single trees using laser scanner. Photogramm J Finland 16:27–42

Kalliovirta J, Laasasenaho J, Kangas A (2005) Evaluation of the laser-relascope. For Ecol Manag 204:181–194

Kangas A, Mehtatalo L, Maltamo M (2007) Modelling percentile based basal area weighted diameter distribution. Silva Fenn 41:425–440

Liaw A, Wiener M (2002) Classification and regression by randomForest. R News 2:18–22

Lilliefors HW (1967) On the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality with mean and variance unknown. J Am Stat Assoc 62:399–402

Liu C, Zhang SY, Lei Y, Newton PF, Zhang L (2004) Evaluation of three methods for predicting diameter distributions of black spruce (Picea mariana) plantations in central Canada. Can J For Res 34:2424–2432

Lumley T, based on Fortran code by Miller A (2017). Leaps: regression subset selection. R package version 3.0

Magnussen S, Renaud JP (2016) Multidimensional scaling of first-return airborne laser echoes for prediction and model-assisted estimation of a distribution of tree stem diameters. Ann For Sci 73:1089–1098

Maltamo M, Gobakken T (2014) Predicting tree diameter distributions. In: Maltamo M, Næsset E, Vauhkonen J (eds) Forestry applications of airborne laser scanning: concepts and cases studies. Springer, Dordrecht – Heidelberg – New York – London, pp 269–292

Maltamo M, Puumalainen J, Päivinen R (1995) Comparison of beta and Weibull functions for modelling basal area diameter distribution in stands of Pinus sylvestris and Picea abies. Scand J Forest Res 10:284–295

Maltamo M, Eerikäinen K, Packalén P, Hyyppä J (2006) Estimation of stem volume using laser scanning-based canopy height metrics. Forestry 79:217–229

Maltamo M, Suvanto A, Packalén P (2007) Comparison of basal area and stem frequency diameter distribution modelling using airborne laser scanner data and calibration estimation. For Ecol Manag 247:26–34

Maltamo M, Næsset E, Bollandsås OM, Gobakken T, Packalén P (2009) Non-parametric prediction of diameter distributions using airborne laser scanner data. Scand J Forest Res 24:541–553

McGaughey RJ (2015) FUSION/LDV: software for LIDAR data analysis and visualization. Version 3.50. USDA Forest Service – Pacific Northwest Research Station. http://forsys.cfr.washington.edu/fusion/fusionlatest.html. Accessed 31 Jan 2016

Montealegre AL, Lamelas MT, Tanase MA, de la Riva J (2014) Forest fire severity assessment using ALS data in a Mediterranean environment. Remote Sens 6:4240–4265

Næsset E, Gobakken T, Holmgren J, Hyyppä H, Hyyppä J, Maltamo M, Nilsson M, Olsson H, Persson Å, Söderman U (2004) Laser scanning of forest resources: the Nordic experience. Scand J Forest Res 19:482–499

Newby MJ (1980) The properties of moment estimators for the Weibull distribution based on the sample coefficient of variation. Technometrics 22:187–194

Packalén P, Maltamo M (2008) Estimation of species-specific diameter distributions using airborne laser scanning and aerial photographs. Can J For Res 38:1750–1760

Parent S, Messier C (1995) Effets d’un gradient de lumière sur la croissance en hauteur et la morphologie de la cime du sapin baumier régénéré naturellement. Can J For Res 25:878–885

Parker RC, Matney TG (1999) Comparison of optical dendrometers for prediction of standing tree volume. For Sci 23:100–107

Pascual C, Mauro F, Hernando A, Martín-Fernández S (2013) Inventory techniques in participatory forest management. In: Martínez-Falero E, Martín-Fernández S, García-Abril A (eds) Quantitative techniques in participatory forest management. CRC Press (Taylor & Francis Group), Boca Ratón, pp 53–134

Persson A, Holmgren J, Söderman U (2002) Detecting and measuring individual trees using an airborne laser scanner. Photogramm Eng Remote Sens 68:925–932

Peuhkurinen J, Mehtätalo L, Maltamo M (2011) Comparing individual tree detection and the area-based statistical approach for the retrieval of forest stand characteristics using airborne laser scanning in Scots pine stands. Can J For Res 41:583–598

Poudel KP, Cao QV (2013) Evaluation of methods to predict Weibull parameters for characterizing diameter distributions. For Sci 59:243–252

R Core Team (2016) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. The Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN) http://wwwR-projectorg/ 01 Dec 2016

Reif DM, Motsinger AA, McKinney BA, Crowe JE, Moore JH (2006) Feature selection using a random forests classifier for the integrated analysis of multiple data types. In: 2006 I.E. Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, Toronto, pp 1–8

Reitberger J, Krzystek P, Stilla U (2008) Analysis of full waveform LIDAR data for the classification of deciduous and coniferous trees. Int J Remote Sens 29:1407–1431

Rodríguez R, Sánchez F, Gorgoso J, Castedo F, López C, Gadow KV (2002) Evaluating standard treatment options for Pinus radiata plantations in Galicia (north-western Spain). Forestry 75:273–284

Schwarz G (1978) Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat 6:461–464

Shang C, Treitz P, Caspersen J, Jones T (2017) Estimating stem diameter distributions in a management context for a tolerant hardwood forest using ALS height and intensity data. Can J Remote Sens 43:79–94

Siipilehto J, Mehtätalo L (2013) Parameter recovery vs. parameter prediction for the Weibull distribution validated for Scots pine stands in Finland. Silva Fenn 47:1–22

Therneau T, Atkinson B, Ripley B (2017). rpart: recursive partitioning and regression trees. R package version 4.1–11. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rpart. Accessed 24 May 2017

Thomas V, Oliver RD, Lim K, Woods M (2008) LiDAR and Weibull modeling of diameter and basal area. For Chron 84:866–875

Treitz P, Lim K, Woods M, Pitt D, Nesbitt D, Etheridge D (2012) LiDAR sampling density for forest resource inventories in Ontario, Canada. Remote Sens 4:830–848

Valbuena R, Maltamo M, Packalen P (2016) Classification of multi-layered forest development classes from low-density national airborne lidar datasets. Forestry 89:392–401

Vihervaara P, Mononen L, Auvinen AP, Virkkala R, Lu Y, Pippuri I, Packalen P, Valbuena R, Valkama J (2015) How to integrate remotely sensed data and biodiversity for ecosystem assessments at landscape scale. Landsc Ecol 30:501–516

Villikka M, Maltamo M, Packalén P, Vehmas M, Hyyppä J (2007) Alternatives for predicting tree-level stem volume of Norway spruce using airborne laser scanner data. Photogramm J Finland 20:33–42

Villikka M, Packalen P, Maltamo M (2012) The suitability of leaf-off airborne laser scanning data in an area-based forest inventory of coniferous and deciduous trees. Silva Fenn 46:99–110

Wagner W, Hollaus M, Briese C, Ducic V (2008) 3D vegetation mapping using small-footprint full-waveform airborne laser scanners. Int J Remote Sens 29:1433–1452

White JC, Wulder MA, Varhola A, Vastaranta M, Coops NC, Cook BD, Pitt D, Woods M (2013) A best practices guide for generating forest inventory attributes from airbone laser scanning data using an area based approach (version 2.0). Information report Canadian Wood Fibre Center FI-X-010 2013

Yu X, Hyyppä J, Vastaranta M, Holopainen M, Viitala R (2011) Predicting individual tree attributes from airborne laser point clouds based on the random forests technique. ISPRS-J Photogramm Remote Sens 66:28–37

Zaffalon M (2005) Credible classification for environmental problems. Environ Model Softw 20:1003–1012

Zellner A, Theil H (1962) Three-stage least squares: simultaneous estimation of simultaneous equations. Econometrica 30:54–78

Funding

Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (AGL2008-02259/FOR); Eduardo González-Ferreiro was financially supported by the Plan galego de investigación, innovación e crecemento 2011-2015 (Plan I2C) (Official Journal of Galicia - DOG nº 52, 17/03/2014 p. 11343, exp: POS-A/2013/049) - Galician Government (Dirección Xeral de Ordenación e Calidade do Sistema Universitario de Galicia - Consellería de Educación e Ordenación Universitaria) and European Social Fund. Manuel Arias-Rodil was financially supported by an FPU grant (AP2012-05337) from the Spanish Ministry of Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Barry Alan Gardiner

This article is part of the Topical Collection on SilviLaser

Contribution of the co-authors

Dr. Manuel Arias-Rodil: designing the experiment, writing the paper, running the data analysis, and supervising the work.

Dr. Ulises Diéguez-Aranda: designing the experiment and writing the paper.

Dr. Juan Gabriel Álvarez-González: running the data analysis and writing the paper

Dr. César Pérez-Cruzado: running the data analysis and writing the paper.

Dr. Fernando Castedo-Dorado: coordinating the research project and writing the paper.

Dr. Eduardo González-Ferreiro: designing the experiment, writing the paper, running the data analysis, and supervising the work.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOC 3622 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arias-Rodil, M., Diéguez-Aranda, U., Álvarez-González, J.G. et al. Modeling diameter distributions in radiata pine plantations in Spain with existing countrywide LiDAR data. Annals of Forest Science 75, 36 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-018-0712-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-018-0712-z