Abstract

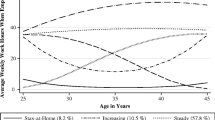

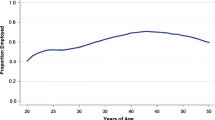

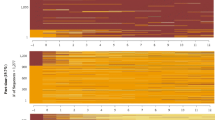

In this article, we consider how individuals’ long-term employment trajectories relate to wage inequality and the gender wage gap in the United States. Using more than 30 years of data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 sample, we identify six employment trajectories for individuals from ages 22 to 50. We find that women across racial/ethnic groups and Black men are more likely than White and Hispanic men to have nonsteady employment trajectories and lower levels of employment throughout their lives, and individuals who have experienced poverty also have heightened risks of intermittent employment. We then assess how trajectories are associated with wages later in careers, at ages 45–50. We find significant variation in wages across work trajectories, with steady high employment leading to the highest wages. This wage variation is primarily explained by work characteristics rather than family characteristics. Finally, we examine gender variation in within-trajectory wages. We find that the gender wage gap is largest in the steady high employment trajectory and is reduced among trajectories with longer durations of nonemployment. Thus, although women are relatively more concentrated in nonsteady trajectories than are men, men who do follow nonsteady wage trajectories incur smaller wage premiums than men in steady high employment pathways, on average. These findings demonstrate that long-term employment paths are important predictors of economic and gender wage inequality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

“Opt out” is in quotation marks because scholarship suggests that leaving work for family is not always voluntary (Stone 2007).

We apply NLSY custom weights, which adjust for attrition in the longitudinal sample (see https://www.nlsinfo.org/weights/nlsy79).

Some studies on long-term employment have used a measure of hours worked rather than employment (e.g., Damaske and Frech 2016). We deviate from this measure to study labor force attachment variation rather than intensity of employment. Although both measures lend unique benefits, the measure that we use allows us to focus on variation in employment versus nonemployment rather than on levels of work.

NLSY uses “Black/Non-Hispanic,” “Hispanic,” and “Non-Black, Non-Hispanic.” We sometimes refer to this last group as “White,” but we recognize that it could include additional racial/ethnic groups as well. See https://www.nlsinfo.org/content/cohorts/nlsy79/topical-guide/household/race-ethnicity-immigration-data.

These are weighted averages.

Hours worked per week are top-coded at 100 per week (5,200 per year), with 7,000+ coded as missing. Our results are robust to these wage and hours coding decisions; models are available upon request.

Results are robust if the dependent variable measures the wages at the oldest working age from ages 45 to 50.

See section 3 of the online appendix for information on missing data.

References

Abendroth, A.-K., Huffman, M. L., & Treas, J. (2014). The parity penalty in life course perspective: Motherhood and occupational status in 13 European countries. American Sociological Review, 79, 993–1014.

Aisenbrey, S., & Bruckner, H. (2008). Occupational aspirations and the gender gap in wages. European Sociological Review, 24, 633–649.

Aisenbrey, S., Evertsson, M., & Grunow, D. (2009). Is there a career penalty for mothers’ time out? A comparison of Germany, Sweden and the United States. Social Forces, 88, 573–605.

Aisenbrey, S., & Fasang, A. (2017). The interplay of work and family trajectories over the life course: Germany and the United States in comparison. American Journal of Sociology, 122, 1448–1484.

Albrecht, J. W., Edin, P.-A., Sundstrom, M., & Vroman, S. B. (1999). Career interruptions and subsequent earnings: A reexamination using Swedish data. Journal of Human Resources, 34, 294–311.

Alon, S., & Haberfeld, Y. (2007). Labor force attachment and the evolving wage gap between White, Black, and Hispanic young women. Work and Occupations, 34, 369–398.

Arulampalam, W. (2001). Is unemployment really scarring? Effects of unemployment experiences on wages. Economic Journal, 111, 585–606.

Avellar, S., & Smock, P. J. (2003). Has the price of motherhood declined over time? A cross-cohort comparison of the motherhood wage penalty. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 597–607.

Bass, B. C. (2015). Preparing for parenthood?: Gender, aspirations, and the reproduction of labor market inequality. Gender & Society, 29, 362–385.

Becker, G. S. (1962). Investment in human capital: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 70(5, Part 2), 9–49.

Becker, G. S. (1983). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Bielby, W. T., & Bielby, D. D. (1992). Cumulative versus continuous disadvantage in an unstructured labor market: Gender differences in the careers of television writers. Work and Occupations, 19, 366–386.

Blau, F. D., Brummund, P., & Liu, A. Y.-H. (2013). Trends in occupational segregation by gender 1970–2009: Adjusting for the impact of changes in the occupational coding system. Demography, 50, 471–492.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2017). The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations. Journal of Economic Literature, 55, 789–865.

Boeckmann, I., Misra, J., & Budig, M. J. (2015). Cultural and institutional factors shaping mothers’ employment and working hours in postindustrial countries. Social Forces, 93, 1301–1333.

Brescoll, V. L., & Uhlmann, E. L. (2005). Attitudes toward traditional and nontraditional parents. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 436–445.

Budig, M. J., & England, P. (2001). The wage penalty for motherhood. American Sociological Review, 66, 204–225.

Cha, Y. (2010). Reinforcing separate spheres: The effect of spousal overwork on men’s and women’s employment in dual-earner households. American Sociological Review, 75, 303–329.

Cha, Y. (2013). Overwork and the persistence of gender segregation in occupations. Gender & Society, 27, 158–184.

Cha, Y., & Weeden, K. A. (2014). Overwork and the slow convergence in the gender gap in wages. American Sociological Review, 79, 457–484.

Coltrane, S., Miller, E. C., DeHaan, T., & Stewart, L. (2013). Fathers and the flexibility stigma. Journal of Social Issues, 69, 279–302.

Correll, S. J., Benard, S., & Paik, I. (2007). Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology, 112, 1297–1339.

Damaske, S., & Frech, A. (2016). Women’s work pathways across the life course. Demography, 53, 365–391.

Elder, G. H., Johnson, M. K., & Crosnoe, R. (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 3–19). Boston, MA: Springer US.

England, P. (1992). Comparable worth: Theories and evidence. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

England, P. (2005). Gender inequality in labor markets: The role of motherhood and segregation. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 12, 264–288.

England, P., Bearak, J., Budig, M. J., & Hodges, M. J. (2016). Do highly paid, highly skilled women experience the largest motherhood penalty? American Sociological Review, 81, 1161–1189.

England, P., Garcia-Beaulieu, C., & Ross, M. (2004). Women’s employment among Blacks, Whites, and three groups of Latinas: Do more privileged women have higher employment? Gender & Society, 18, 494–509.

Eriksson, S., & Rooth, D.-O. (2014). Do employers use unemployment as a sorting criterion when hiring? Evidence from a field experiment. American Economic Review, 104, 1014–1039.

Evertsson, M. (2016). Parental leave and careers: Women’s and men’s wages after parental leave in Sweden. Advances in Life Course Research, 29, 26–40.

Fernandez-Mateo, I. (2009). Cumulative gender disadvantage in contract employment. American Journal of Sociology, 114, 871–923.

Flippen, C., & Tienda, M. (2000). Pathways to retirement: Patterns of labor force participation and labor market exit among the pre-retirement population by race, Hispanic origin, and sex. Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 55, S14–S27.

Frech, A., & Damaske, S. (2019). Men’s income trajectories and physical and mental health at midlife. American Journal of Sociology, 124, 1372–1412.

FRED. (2017, May 11). Good news for women in the labor force? [Federal Reserve Economic Data blog]. Retrieved from https://fredblog.stlouisfed.org/2017/05/good-news-for-women-in-the-labor-force/

Frytak, J. R., Harley, C. R., & Finch, M. D. (2003). Socioeconomic status and health over the life course. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 623–643). Boston, MA: Springer US.

Fuegen, K., Biernat, M., Haines, E., & Deaux, K. (2004). Mothers and fathers in the workplace: How gender and parental status influence judgments of job-related competence. Journal of Social Issues, 60, 737–754.

Gangl, M. (2006). Scar effects of unemployment: An assessment of institutional complementarities. American Sociological Review, 71, 986–1013.

Gangl, M., & Ziefle, A. (2009). Motherhood, labor force behavior, and women’s careers: An empirical assessment of the wage penalty for motherhood in Britain, Germany, and the United States. Demography, 46, 341–369.

Gangl, M., & Ziefle, A. (2015). The making of a good woman: Extended parental leave entitlements and mothers’ work commitment in Germany. American Journal of Sociology, 121, 511–563.

García-Manglano, J. (2015). Opting out and leaning in: The life course employment profiles of early baby boom women in the United States. Demography, 52, 1961–1993.

Gerstel, N., & Clawson, D. (2014). Class advantage and the gender divide: Flexibility on the job and at home. American Journal of Sociology, 120, 395–431.

Gerstel, N., & Clawson, D. (2018). Control over time: Employers, workers, and families shaping work schedules. Annual Review of Sociology, 44, 77–97.

Glauber, R. (2008). Race and gender in families and at work: The fatherhood wage premium. Gender & Society, 22, 8–30.

Glauber, R., & Gozjolko, K. L. (2011). Do traditional fathers always work more? Gender ideology, race, and parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73, 1133–1148.

Gough, M., & Noonan, M. (2013). A review of the motherhood wage penalty in the United States. Sociology Compass, 7, 328–342.

Halpern-Manners, A., Warren, J. R., Raymo, J. M., & Nicholson, D. A. (2015). The impact of work and family life histories on economic well-being at older ages. Social Forces, 93, 1369–1396.

Han, S.-K., & Moen, P. (1999). Work and family over time: A life course approach. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 562, 98–110.

Hegewisch, A., & Williams-Baron, W. (2018). The gender wage gap: 2017 earnings differences by race and ethnicity (IWPR Fact Sheet Report #C464). Washington, DC: Institute for Women’s Policy Research. Retrieved from https://iwpr.org/publications/gender-wage-gap-2017-race-ethnicity/

Hodges, M. J., & Budig, M. J. (2010). Who gets the daddy bonus? Organizational hegemonic masculinity and the impact of fatherhood on earnings. Gender & Society, 24, 717–745.

Hotchkiss, J. L., & Pitts, M. M. (2007). The role of labor market intermittency in explaining gender wage differentials. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 97, 417–421.

Hynes, K., & Clarkberg, M. (2005). Women’s employment patterns during early parenthood: A group-based trajectory analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 222–239.

Jacobs, J. A., & Gerson, K. (2001). Overworked individuals or overworked families? Explaining trends in work, leisure, and family time. Work and Occupations, 28, 40–63.

Jacobsen, J. P., & Levin, L. M. (1995). Effects of intermittent labor force attachment on women’s earnings. Monthly Labor Review, 118(9), 14–19.

Jones, B. L., & Nagin, D. S. (2013). A note on a Stata plugin for estimating group-based trajectory models. Sociological Methods & Research, 42, 608–613.

Kalleberg, A. L. (2000). Nonstandard employment relations: Part-time, temporary and contract work. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 341–365.

Kalleberg, A. L. (2011). Good jobs, bad jobs: The rise of polarized and precarious employment systems in the United States, 1970s to 2000s. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Killewald, A., & Zhuo, X. (2019). U.S. mothers’ long-term employment patterns. Demography, 56, 285–320.

Landivar, L. C. (2014). Opting out, scaling back, or business-as-usual? An occupational assessment of women’s employment. Sociological Forum, 29, 189–214.

Landivar, L. C. (2017). Mothers at work: Who opts out? Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Lu, Y., Wang, J. S.-H., & Han, W.-J. (2017). Women’s short-term employment trajectories following birth: Patterns, determinants, and variations by race/ethnicity and nativity. Demography, 54, 93–118.

Lundberg, S., & Rose, E. (2000). Parenthood and the earnings of married men and women. Labour Economics, 7, 689–710.

Lyness, K. S., Gornick, J. C., Stone, P., & Grotto, A. R. (2012). It’s all about control: Worker control over schedule and hours in cross-national context. American Sociological Review, 77, 1023–1049.

Macmillan, R., & Copher, R. (2005). Families in the life course: Interdependency of roles, role configurations, and pathways. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 858–879.

Nagin, D. S. (2005). Group-based modeling of development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nelson, M. K., & Smith, J. (1999). Working hard and making do: Surviving in small town America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

O’Rand, A. M. (1996). The precious and the precocious: Understanding cumulative disadvantage and cumulative advantage over the life course. Gerontologist, 36, 230–238.

Patterson, S. E., Damaske, S., & Sheroff, C. (2017). Gender and the MBA: Differences in career trajectories, institutional support, and outcomes. Gender & Society, 31, 310–332.

Pedulla, D. S. (2016). Penalized or protected? Gender and the consequences of nonstandard and mismatched employment histories. American Sociological Review, 81, 262–289.

Percheski, C. (2018). Marriage, family structure, and maternal employment trajectories. Social Forces, 96, 1211–1242.

Ridgeway, C. L., & Correll, S. J. (2004). Motherhood as a status characteristic. Journal of Social Issues, 60, 683–700.

Rivera, L. A., & Tilcsik, A. (2016). Class advantage, commitment penalty: The gendered effect of social class signals in an elite labor market. American Sociological Review, 81, 1097–1131.

Roehling, P. V., Roehling, M. V., & Moen, P. (2001). The relationship between work-life policies and practices and employee loyalty: A life course perspective. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 22, 141–170.

Rudman, L. A., & Mescher, K. (2013). Penalizing men who request a family leave: Is flexibility stigma a femininity stigma? Journal of Social Issues, 69, 322–340.

Spivey, C. (2005). Time off at what price? The effects of career interruptions on earnings. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 59, 119–140.

Stone, P. (2007). Opting out? Why women really quit careers and head home. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Stone, P., & Hernandez, L. A. (2013). The all-or-nothing workplace: Flexibility stigma and “opting out” among professional-managerial women. Journal of Social Issues, 69, 235–256.

Stone, P., & Lovejoy, M. (2019). Opting back in: What really happens when mothers go back to work. Oakland: University of California Press.

Theunissen, G., Verbruggen, M., Forrier, A., & Sels, L. (2011). Career sidestep, wage setback? The impact of different types of employment interruptions on wages. Gender, Work and Organization, 18(Suppl. 1), e110–e131. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2009.00471.x

Vandello, J. A., Hettinger, V. E., Bosson, J. K., & Siddiqi, J. (2013). When equal isn’t really equal: The masculine dilemma of seeking work flexibility. Journal of Social Issues, 69, 303–321.

Webber, G., & Williams, C. (2008). Mothers in “good” and “bad” part-time jobs: Different problems, same results. Gender & Society, 22, 752–777.

Weeden, K. A., Cha, Y., & Bucca, M. (2016). Long work hours, part-time work, and trends in the gender gap in pay, the motherhood wage penalty, and the fatherhood wage premium. Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(4), 71–102.

Weisshaar, K. (2018). From opt out to blocked out: The challenges for labor market re-entry after family-related employment lapses. American Sociological Review, 83, 34–60.

Wessel, D. (2015, September 18). The typical male U.S. worker earned less in 2014 than in 1973 (Brookings Op-Ed). Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/the-typical-male-u-s-worker-earned-less-in-2014-than-in-1973/

Williams, J. C., & Boushey, H. (2010). The three faces of work-family conflict (Work-Life-Law report). Washington, DC: Center for American Progress, UC Hastings College of the Law.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Michael Rosenfeld, Koji Chavez, Ariela Schachter, Ted Mouw, and Demography reviewers and editors for comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. The NLSY79 survey is sponsored and directed by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and conducted by the Center for Human Resource Research at The Ohio State University. Interviews are conducted by the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago. Both authors contributed equally to this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 200 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weisshaar, K., Cabello-Hutt, T. Labor Force Participation Over the Life Course: The Long-Term Effects of Employment Trajectories on Wages and the Gendered Payoff to Employment. Demography 57, 33–60 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00845-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00845-8