Abstract

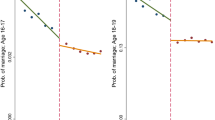

Research has documented a negative association between women’s educational attainment and early sexual intercourse, union formation, and pregnancy. However, the implications that school progression relative to age may have for the timing and order of such transitions are poorly understood. In this article, I argue that educational attainment has different implications depending on a student’s progression through school grades relative to her age. Using month of birth and age-at-school-entry policies to estimate the effect of advanced school progression by age, I show that it accelerates the occurrence of family formation and sexual onset among teenage women in Mexico. Focusing on girls aged 15–17 interviewed by a national survey, I find that those who progress through school ahead of their birth cohort have a higher probability of having had sex, been pregnant, and cohabited by the time of interview. I argue that this pattern of behaviors is explained by experiences that lead them to accelerate their transition to adulthood compared with same-age students with fewer completed school grades, such as exposure to relatively older peers in school and completing academic milestones earlier in life. Among girls who got pregnant, those with an advanced school progression by age are more likely to engage in drug use, alcohol consumption, and smoking before conception; more likely to have pregnancy-related health complications; and less likely to attend prenatal care visits. Thus, an advanced school progression by age has substantial implications for the health and well-being of young women, with potential intergenerational consequences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Low- and middle-income here are defined according to the United Nation's income-based country categories (United Nations 2018).

In contrast, in Norway, Sweden, and the United States, less than 4 % of girls aged 12–14, and less than 10 % of those aged 15–17 were out of school as of 2012 (UIS 2015).

Past studies have also assessed the effect of school starting age on other outcomes, such as educational attainment and earnings in the United States (Angrist and Keueger 1991; Dobkin and Ferreira 2010) and Sweden (Fredriksson and Öckert 2013), although results have been mixed and highly dependent on the configuration of compulsory schooling laws in each country.

However, given the compulsory schooling laws in North Carolina, Cook and Kang (2016) also found that late starters are more likely to drop out of high school and commit a felony offense by age 19.

About 16 % of women with an ASPA in the data had actually completed two more school grades than expected for their age, possibly because having a daughter born in August makes it easier for parents to negotiate her school enrollment before age 6, despite it being unusual. The other 84 % had completed only one more grade, as expected. The results of all the analyses remain unchanged if the 16 % of women with the most advanced school progression are excluded. But for simplicity, throughout this article, I refer to the entire group of women with an ASPA as having completed one more grade than expected for their age.

This is an instrument similar to that used by Angrist and Keueger (1991), with the exception that this analysis does not use the combination of compulsory schooling laws and month of birth as an instrumental variable.

This is true for girls who are still enrolled in school or for those who have dropped out and spent less than one school year out of school. For girls who dropped out more than a school year before the interview date, this variable is not informative. To test the sensitivity of results to this limitation, I estimated the same bivariate probit models excluding girls who did not complete any grade beyond elementary school (seventh grade or higher) because they are likely to have abandoned school more than a school year before the interview date. Results using this restricted sample are closely similar to those in Table 4.

I exclude from the analysis girls born during September because they are less likely to follow the age-at-school-entry rule. Given that their date of birth would be less than a month away from the cutoff, school officials commonly allow children born in September to enroll before they turn age 6, even if their birth date is not September 1. Focusing the analysis on girls born in August and October reduces uncertainty in enrollment practices for children born in September.

Preschool education was neither mandatory nor widely available in Mexico between 1994 and 2001, which is the year range within which the women in the study (born between 1991 and 1998) would have become 3 years old.

I use a homogenized age-at-interview variable that records full years of age in July of the corresponding interview year. Because interview dates in the 2014 wave ranged from August to September, some respondents were n years old at the time of interview, while some of their counterparts born within less than three months had already turned n + 1. If full years of age at the exact interview date were included in the model as a control for age, they would distort the real distance in biological age for respondents who have a birth date in August. The homogenized age at interview used in the models is perfectly collinear with year of birth, which is not included as a covariate.

This implied excluding 15 % of girls born in October and 17 % of girls born in August among those who had ever been pregnant.

The sample contains too few miscarriage and stillbirth cases to be able to assess the effect of month of birth on the prevalence of each of these outcomes separately.

References

Angrist, J. D., & Keueger, A. B. (1991). Does compulsory school attendance affect schooling and earnings? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 4, 979–1014.

Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Arceo-Gomez, E. O., & Campos-Vazquez, R. M. (2014). Teenage pregnancy in Mexico: Evolution and consequences. Latin American Journal of Economics, 51, 109–146.

Argys, L. M., & Rees, D. I. (2008). Searching for peer group effects: A test of the contagion hypothesis. Review of Economics and Statistics, 90, 442–458.

Armour, S., & Haynie, D. L. (2007). Adolescent sexual debut and later delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 141–152.

Axinn, W. G., & Barber, J. S. (2001). Mass education and fertility transition. American Sociological Review, 66, 481–505.

Basu, A. M. (2002). Why does education lead to lower fertility? A critical review of some of the possibilities. World Development, 30, 1779–1790.

Bedard, K., & Dhuey, E. (2006). The persistence of early childhood maturity: International evidence of long-run age effects. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121, 1437–1472.

Binder, M., & Woodruff, C. (2002). Inequality and intergenerational mobility in schooling: The case of Mexico. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 50, 249–267.

Black, S. E., Devereux, P. J., & Salvanes, K. G. (2008). Staying in the classroom and out of the maternity ward? The effect of compulsory schooling laws on teenage births. Economic Journal, 118, 1025–1054.

Black, S. E., Devereux, P. J., & Salvanes, K. G. (2011). Too young to leave the nest? The effects of school starting age. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93, 455–467.

Blossfeld, H.-P., & Huinink, J. (1991). Human capital investments or norms of role transition? How women’s schooling and career affect the process of family formation. American Journal of Sociology, 97, 143–168.

Bonell, C., Allen, E., Strange, V., Copas, A., Oakley, A., Stephenson, J., & Johnson, A. (2005). The effect of dislike of school on risk of teenage pregnancy: Testing of hypotheses using longitudinal data from a randomised trial of sex education. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 59, 223–230.

Branson, N., Ardington, C., & Leibbrandt, M. (2015). Health outcomes for children born to teen mothers in Cape Town, South Africa. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 63, 589–616.

Chen, X.-K., Wen, S. W., Fleming, N., Demissie, K., Rhoads, G. G., & Walker, M. (2007). Teenage pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes: A large population based retrospective cohort study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36, 368–373.

Chiburis, R. C., Das, J., & Lokshin, M. (2011). A practical comparison of the bivariate probit and linear IV estimators (English; Policy Research Working Paper No. 5601). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Clark, S., & Mathur, R. (2012). Dating, sex, and schooling in urban Kenya. Studies in Family Planning, 43, 161–174.

CONAPO. (2012). Índices de marginación [Poverty indices]. Mexico City, Mexico: Consejo Nacional de Población. Retrieved from http://www.conapo.gob.mx/es/CONAPO/Indices_de_Marginacion

Conde-Agudelo, A., Belizán, J. M., & Lammers, C. (2005). Maternal-perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with adolescent pregnancy in Latin America: Cross-sectional study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 192, 342–349.

Cook, P. J., & Kang, S. (2016). Birthdays, schooling, and crime: Regression-discontinuity analysis of school performance, delinquency, dropout, and crime initiation. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 8(1), 33–57.

Depew, B., & Eren, O. (2016). Born on the wrong day? School entry age and juvenile crime. Journal of Urban Economics, 96, 73–90.

Diario Oficial de la Federación. (1993). DECRETO que declara reformados los artículos 30 y 31 fracción I, de la Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos [DECREE reforming articles 30. and 31 section I, of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States]. Mexico City, Mexico: Secretaría de Gobernación, Diario Oficial de la Federación. Retrieved from http://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=4721720&fecha=05/03/1993

Diario Oficial de la Federación. (1996). ACUERDO número 209 mediante el cual se reforma y adiciona el diverso número 181 por el que se establecen el Plan y los Programas de Estudio para la Educación Primaria [AGREEMENT number 209 reforming and adding section number 181 to establish the Plan and Study Programs for Primary Education]. Mexico City, Mexico: Secretaría de Gobernación, Diario Oficial de la Federación. Retrieved from http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=4875438&fecha=13/03/1996

Diario Oficial de la Federación. (2006). DECRETO por el que se adiciona un segundo párrafo a la fracción I del artículo 65 de la Ley General de Educación [DECREE adding a second paragraph to fraction I of article 65 in the General Law of Education]. Mexico City, Mexico: Secretaría de Gobernación, Diario Oficial de la Federación. Retrieved from https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=4911866&fecha=20/06/2006

Diario Oficial de la Federación (2012). DECRETO por el que se declara reformado el párrafo primero; el inciso (c) de la fracción II y la fracción V del artículo 3o., y la fracción I del artículo 31 de la Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos [DECREE declaring the first paragraph amended; subsection (c) of fraction II and section V of article 3, and section I of article 31 of the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States]. Mexico City, Mexico: Secretaría de Gobernación, Diario Oficial de la Federación. Retrieved from http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5233070&fecha=09/02/2012&print=true

Dincer, M. A., Kaushal, N., & Grossman, M. (2014). Women’s education: Harbinger of another spring? Evidence from a natural experiment in Turkey. World Development, 64, 243–258.

Dobkin, C., & Ferreira, F. (2010). Do school entry laws affect educational attainment and labor market outcomes? Economics of Education Review, 29, 40–54.

Echarri-Cánovas, C. J., & Pérez-Amador, K. (2007). En tránsito hacia la adultez: Eventos en el curso de vida de los jóvenes en México [Heading toward adulthood: Events in the life course of young people in Mexico]. Estudios Demográficos y Urbanos, 22, 43–77. https://doi.org/10.24201/edu.v22i1.1293

Ekert-Jaffe, O., & Stier, H. (2009). Normative or economic behavior? Fertility and women’s employment in Israel. Social Science Research, 38, 644–655.

Eloundou-Enyegue, P. M. (2004). Pregnancy-related dropouts and gender inequality in education: A life-table approach and application to Cameroon. Demography, 41, 509–528.

Fall, C. H. D., Sachdev, H. S., Osmond, C., Restrepo-Mendez, M. C., Victora, C., Martorell, R., . . . COHORTS Investigators. (2015). Association between maternal age at childbirth and child and adult outcomes in the offspring: A prospective study in five low-income and middle-income countries (COHORTS Collaboration). Lancet Global Health, 3, e366–e377. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00038-8

Fredriksson, P., & Öckert, B. (2013). Life-cycle effects of age at school start. Economic Journal, 124, 977–1004.

Hotz, V. J., McElroy, S. W., & Sanders, S. G. (2005). Teenage childbearing and its life cycle consequences: Exploiting a natural experiment. Journal of Human Resources, 50, 683–715.

Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación (INEE). (2006). Panorama educativo de México 2006: Indicadores del sistema educativo nacional [Educational panorama of Mexico 2006: Indicators of the national education system]. Mexico City, Mexico: Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación. Retrieved from http://publicaciones.inee.edu.mx/buscadorPub/P1/B/104/P1B104.pdf

Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación (INEE). (2016). Panorama educativo de México 2015: Indicadores del sistema educativo nacional: Educación básica y media superior [Educational panorama of Mexico 2015: Indicators of the national education system: Basic education and high school]. Mexico City, Mexico: Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación. Retrieved from http://publicaciones.inee.edu.mx/buscadorPub/P1/B/114/P1B114.pdf

Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación (INEE). (2017). La educación obligatoria en México: Informe 2017 [Compulsory education in Mexico: 2017 report]. Mexico City, Mexico: Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación. Retrieved from http://publicaciones.inee.edu.mx/buscadorPub/P1/I/242/P1I242.pdf

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). (2016a). Encuestas en hogares [Household surveys] [Data sets]. Aguascalientes City, Aguascalientes, Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Retrieved from http://www.beta.inegi.org.mx/datos/?init=2

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). (2016b). Sistema Estatal y Municipal de Bases de Datos (SIMBAD) [State and municipal system of databases] [Database]. Aguascalientes City, Aguascalientes, Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Retrieved from http://sc.inegi.org.mx/cobdem/

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). (2017). Natalidad: Microdatos de actas de nacimiento [Births: Birth certificates microdata] [Data sets]. Aguascalientes City, Aguascalientes, Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Retrieved from https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/natalidad/default.html#Microdatos

Kaestle, C. E., Halpern, C. T., Miller, W. C., & Ford, C. A. (2005). Young age at first sexual intercourse and sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Epidemiology, 16, 774–780.

Kalmijn, M., Loeve, A., & Manting, D. (2007). Income dynamics in couples and the dissolution of marriage and cohabitation. Demography, 44, 159–179.

Kendler, K. S., Myers, J., Damaj, M. I., & Chen, X. (2013). Early smoking onset and risk for subsequent nicotine dependence: A monozygotic co-twin control study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 408–413.

Lam, D., Marteleto, L., & Ranchhod, V. (2013). The influence of older classmates on adolescent sexual behavior in Cape Town, South Africa. Studies in Family Planning, 44, 147–167.

Lassi, Z. S., Imam, A. M., Dean, S. V., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2014). Preconception care: Caffeine, smoking, alcohol, drugs and other environmental chemical/radiation exposure. Reproductive Health, 11(Suppl. 3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-11-S3-S6

Lee, D. (2010). The early socioeconomic effects of teenage childbearing: A propensity score matching approach. Demographic Research, 23, 697–736. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2010.23.25

Lehrer, E. L. (2008). Age at marriage and marital instability: Revisiting the Becker-Landes-Michael hypothesis. Journal of Population Economics, 21, 463–484.

Lloyd, C. B. (2005). Growing up global: The changing transitions to adulthood in developing countries. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Loewenstein, G., & Furstenberg, F. (1991). Is teenage sexual behavior rational? Journal of Applied Psychology, 21, 957–986.

López-Acevedo, G. (2006). Mexico: Two decades of the evolution of education and inequality (Policy Research Working Paper No. 3919). Washington, DC: World Bank.

Lynskey, M. T., Heath, A. C., Bucholz, K. K., Slutske, W. S., Madden, P. A. F., Nelson, E. C., . . . Martin, N. G. (2003). Escalation of drug use in early-onset cannabis users vs co-twin controls. JAMA, 289, 427–433.

Macleod, C. I., & Tracey, T. (2010). A decade later: Follow-up review of South African research on the consequences of and contributory factors in teen-aged pregnancy. South African Journal of Psychology, 40, 18–31.

Mahavarkar, S. H., Madhu, C. K., & Mule, V. D. (2008). A comparative study of teenage pregnancy. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 28, 604–607.

Mateja, W. A., Nelson, D. B., Kroelinger, C. D., Ruzek, S., & Segal, J. (2012). The association between maternal alcohol use and smoking in early pregnancy and congenital cardiac defects. Journal of Women’s Health, 21, 26–34.

McCrary, J., & Royer, H. (2011). The effect of female education on fertility and infant health: Evidence from school entry policies using exact date of birth. American Economic Review, 101, 158–195.

McGue, M., & Iacono, W. G. (2005). The association of early adolescent problem behavior with adult psychopathology. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 1118–1124.

McLanahan, S. S., & Kelly, E. L. (2006). The feminization of poverty: Past and future. In J. S. Chafetz (Ed.), Handbook of the sociology of gender (pp. 127–146). New York, NY: Springer.

McLanahan, S., & Percheski, C. (2008). Family structure and the reproduction of inequalities. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 257–276.

McLanahan, S., Tach, L., & Schneider, D. (2013). The causal effects of father absence. Annual Review of Sociology, 39, 399–427.

Monstad, K., Propper, C., & Salvanes, K. G. (2008). Education and fertility: Evidence from a natural experiment. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 110, 827–852.

Nour, N. M. (2006). Health consequences of child marriage in Africa. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 12, 1644–1649.

Nour, N. M. (2009). Child marriage: A silent health and human rights issue. Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2, 51–56.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2009). PISA data analysis manual. Paris, France: OECD. http://archivos.agenciaeducacion.cl/Manual_de_Analisis_de_datos_SPSS_version_ingles.pdf

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). (2013). PISA 2012 assessment and analytical framework: Mathematics, reading, science, problem solving, and financial literacy. Paris, France: OECD. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisaproducts/PISA%202012%20framework%20e-book_final.pdf

Öst, C. E. (2012). Housing and children: Simultaneous decisions? A cohort study of young adults’ housing and family formation decision. Journal of Population Economics, 25, 349–266.

Pallas, A. M. (1993). Schooling in the course of human lives: The social context of education and the transition to adulthood in industrial society. Review of Educational Research, 63, 409–447.

Pallas, A. M. (2003). Educational transitions, trajectories, and pathways. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 165–184). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer Academic.

Population Reference Bureau. (2013). 2013 world population data sheet. Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau. Retrieved from http://www.prb.org/pdf13/2013-population-data-sheet_eng.pdf

Raj, A., Saggurti, N., Winter, M., Labonte, A., Decker, M. R., Balaiah, D., & Silverman, J. G. (2010). The effect of maternal child marriage on morbidity and mortality of children under 5 in India: Cross sectional study of a nationally representative sample. BMJ, 340. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b4258

Rendall, M. S., & Parker, S. W. (2014). Two decades of negative educational selectivity of Mexican migrants to the United States. Population and Development Review, 40, 421–446.

Ribar, D. (1994). Teenage fertility and high school completion. Review of Economics and Statistics, 76, 413–424.

Ritchwood, T. D., Ford, H., DeCoster, J., Sutton, M., & Lochman, J. E. (2015). Risky sexual behavior and substance use among adolescents: A meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 52, 74–88.

Rubalcava, L., & Teruel, G. (2013). Mexican Family Life Survey, Third Wave (Working paper). Retrieved from www.ennvih-mxfls.org

Secretaría de Educación Pública (SEP). (2000). Perfil de la Educación en México [Profile of education in Mexico]. Mexico City, Mexico: SEP Retrieved from http://planeacion.uaemex.mx/InfBasCon/PerfildelaEducacionenMexico.pdf

Skirbekk, V., Kohler, H.-P., & Prskawetz, A. (2004). Birth month, school graduation, and the timing of births and marriages. Demography, 41, 547–568.

Sosa, C. G., Althabe, F., Belizán, J. M., & Buekens, P. (2009). Risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage in vaginal deliveries in a Latin-American population. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 113, 1313–1319.

Stern, C., & Menkes, C. (2008). Embarazo adolescente y estratificación social [Adolescent pregnancy and social stratification]. In S. Lerner & I. Szasz (Eds.), Salud reproductiva y condiciones de vida en México, Tomo I [Reproductive health and living conditions in Mexico, Vol. 1]. Mexico City, Mexico: El Colegio de México.

Timaeus, I. M., & Moultrie, T. A. (2015). Teenage childbearing and educational attainment in South Africa. Studies in Family Planning, 46, 143–160.

UNESCO. (2016). Education for people and planet: Creating sustainable futures for all (Global Education Monitoring Report). Paris, France: UNESCO. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002457/245752e.pdf

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). (2015). User guide for UIS.STAT. Montreal, Canada: UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved from http://data.uis.unesco.org/Content/themes/UIS/static/help/WBOS User Guide (EN).PDF

UNICEF. (2016). Niñas y niños fuera de la escuela [Girls and boys out of school]. Mexico City, Mexico: Publicaciones de UNICEF México. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/mexico/spanish/UNICEF_NFE_MEX.pdf

United Nations. (2015). World fertility patterns 2015: Data booklet (ST/ESA/SER.A/370). New York, NY: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/fertility/world-fertility-patterns-2015.pdf

United Nations. (2018). World economic situation and prospects 2018. New York, NY: United Nations. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/publication/WESP2018_Full_Web-1.pdf

Vieira, C. L., Coeli, C. M., Pinheiro, R. S., Brandão, E. R., Camargo, K. R., Jr., & Aguilar, F. P. (2012). Modifying effect of prenatal care on the association between young maternal age and adverse birth outcomes. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 25, 185–189.

Wand, H., & Ramjee, G. (2012). The relationship between age of coital debut and HIV seroprevalence among women in Durban, South Africa: A cohort study. BMJ Open, 2. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000285

Warner, L. A. (2003). Longitudinal effects of age at onset and first drinking situations on problem drinking. Substance Use & Misuse, 38, 1983–2016.

Zuilowski, S. S., & Jukes, M. C. H. (2012). The impact of education on sexual behavior in sub-Saharan Africa: A review of the evidence. AIDS Care, 24, 562–576.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to Florencia Torche, Paula England, Lawrence Wu, Julia Behrman, José Ortiz, Andrés Villarreal, Michael Rendall, three anonymous reviewers, and the members of the New York University Inequality Workshop for their valuable comments on previous drafts. All remaining errors are my own. I gratefully acknowledge support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Center for Child Health and Human Development Grant P2C-HD041041, Maryland Population Research Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 52.7 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Caudillo, M.L. Advanced School Progression Relative to Age and Early Family Formation in Mexico. Demography 56, 863–890 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00782-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00782-6